So we have two modes of politics. One that depends on your subject position and one that doesn’t. And we have two kinds of art: one that depends on your subject position and one that doesn’t. And they align themselves, one with the other, according to what they assume about representation and about truth. Which kind of art is Miró’s? Or is it another kind altogether? And what kind of politics does it embody?

…if we wanted the unrich to stop being such a (vastly) underrepresented minority in our universities, we’d have to throw most of our current students out. From this standpoint, the most effective version of an occupy movement on campuses like Michigan’s would be one in which the students stopped occupying it and made way for not the 99% but the 75% who have been systematically denied admission.

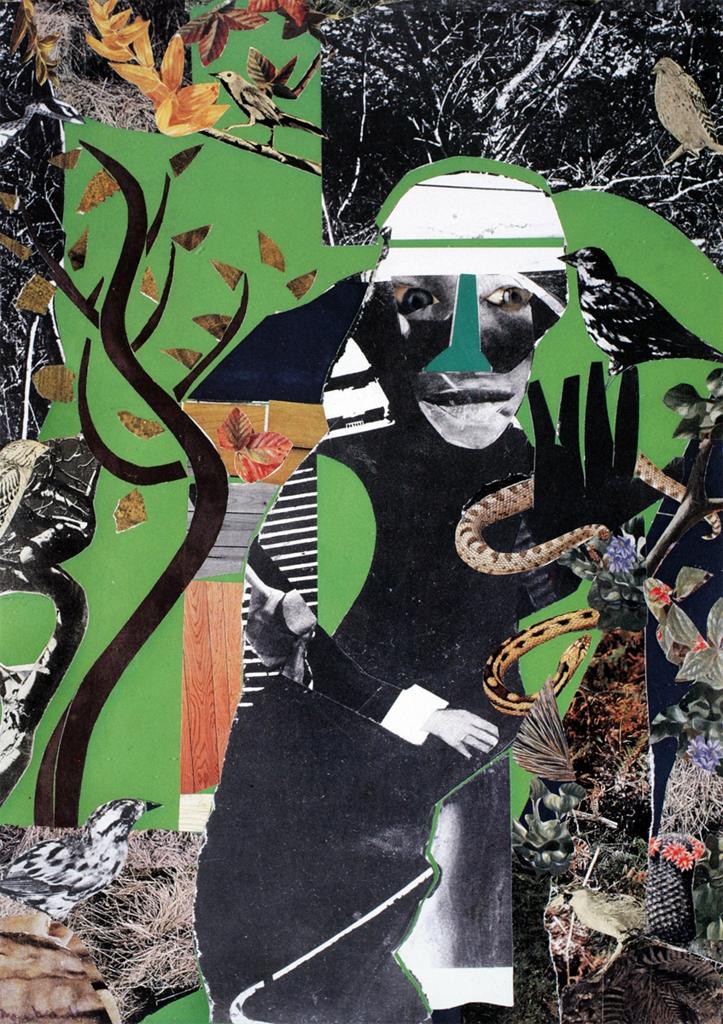

Bearden wanted his collages to conjure. Of course, all representational images conjure in the sense that they gather together colors and shapes to form an image of the world and in so doing call to the minds of their viewers various ideas, emotions, associations, and memories. But in making the conjur woman so prevalent in his imagery and in adopting the medium of collage, which by its very nature extracts material from the world and then transmutes it, turning so many scraps of paper into a novel physical form, Bearden suggested that he had in mind for his art an instrumentality beyond the norm, a capacity, akin to that of the conjur woman, that exceeded human limits and approximated new ways of seeing and being.

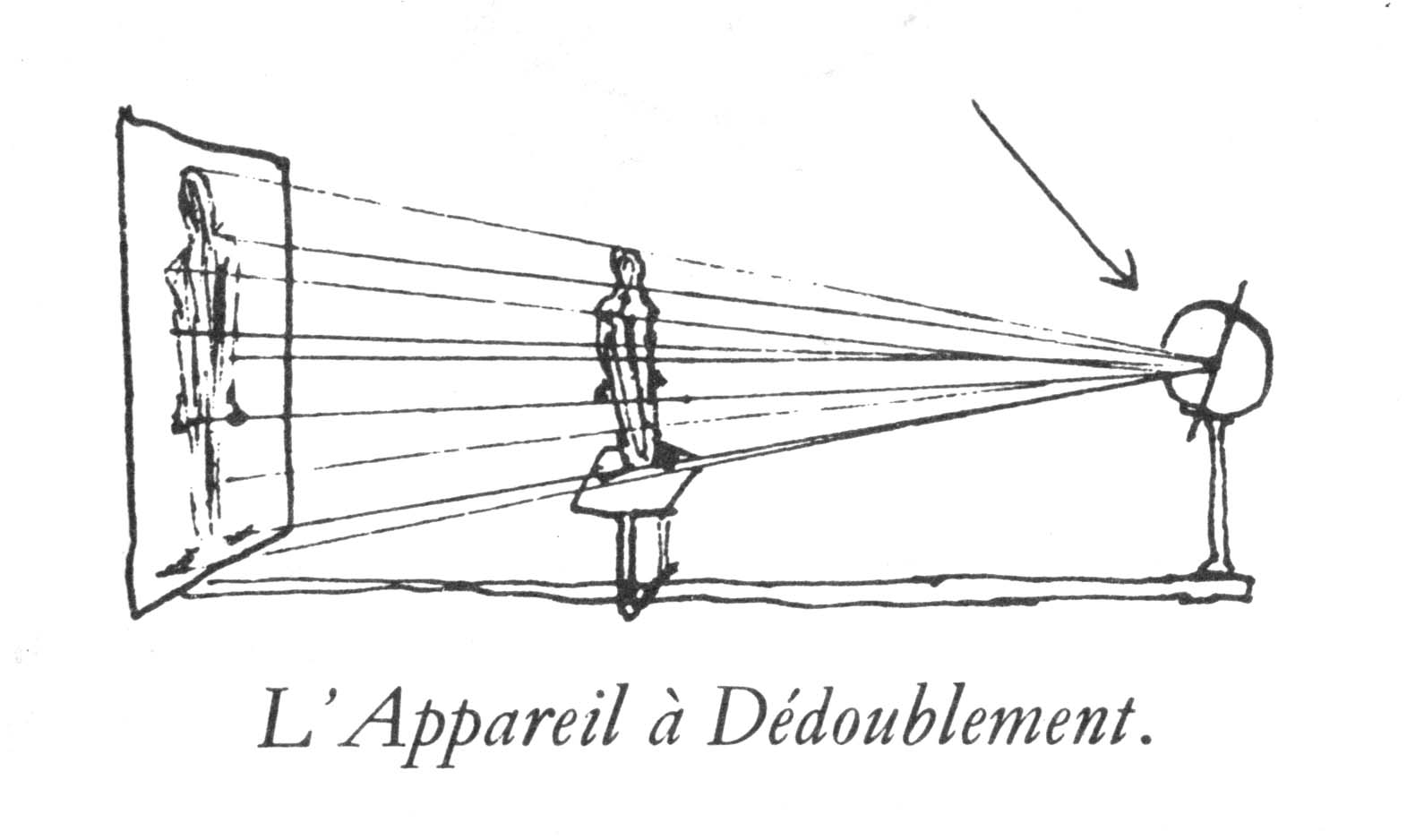

In excavating the optische Schichten in which artworks—that is, drawings, paintings, sculptures, and so on—are constituted…post-formalist art history calls for histories of the aesthetic orders and structures (as it were the “art”) of human vision, of imaging and envisioning, that is, of its active imaginative force whether or not any actual historical artwork was (or is) in vision or in view. The optical appearance of visual artworks—the supposed object of Wöfflinian formalism—is becoming less important analytically than the configuring force of imaging, regardless of what is imaged.

BY Lisa Florman

The combination of flatness, enframing, and the implied interchangeability of consumer goods that we see in Warhol’s Soup Cans is both characteristic and telling. In front of such works, I can only think of what the philosopher Martin Heidegger referred to as the “standing reserve.” Insofar as our present sense of reality is shaped by the technological age in which we live, we increasingly treat all entities, Heidegger claimed, as intrinsically meaningless “resources,” a “reserve” standing by merely to be optimized and ordered for maximally flexible use.

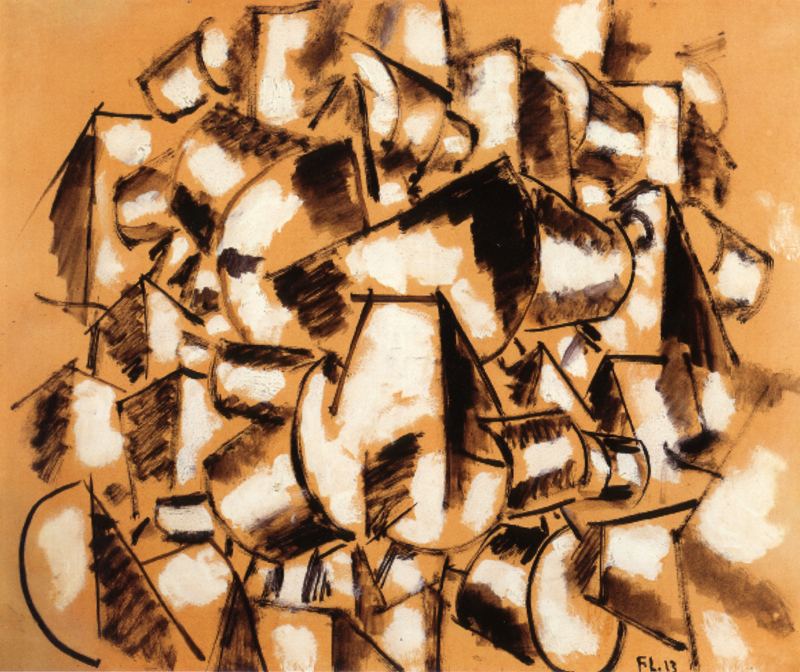

In the case of Ballet mécanique, however, it is no longer a question of competing with or dominating spectacular vision from within painting. Opting for a different strategy, Léger works against cinematic absorption and the pseudo-intensity of cinema from within cinema itself.

There is a deep schism within Pollock criticism. Taking Pollock’s marks to index the artist’s activity elevates the causes of his paintings over their meanings, with the consequence that his works of art are reduced to intentionless surfaces that just register his “traces.” That position implicitly requires us to reject the status of a painting as a medium of expression, and treat it instead as an occasion for a viewer’s experience. But Pollock’s project–one that finds its most rigorous articulation in formalist accounts of his art–is based on demarcating the actual from the representational, the literal surface from pictorial meaning.

When Max Beckmann (1884-1950) painted The Synagogue in 1919, he could not have anticipated the ways in which it would come to be viewed and interpreted. His critics were the first to weigh in after World War I with poetic analyses. Subsequent viewers – including museum and municipal officials – placed less emphasis on the painting’s purely formal values. Since 1945, The Synagogue’s prophetic quality and historical function as well as its political uses and pedagogical applications have shaped its reception. Eschewing an interpretive mastery of the painting, this essay considers the viewer’s varied response to Beckmann’s picture as evidence of its radical authenticity.

BY Todd Cronan

In one of his last interviews Michel Foucault famously said “As far as I’m concerned, Marx doesn’t exist.” What he meant was that “Marx” as an author was something largely fabricated from concepts borrowed from the eighteenth century, in particular the writings of David Ricardo. From Ricardo he derived his most crucial idea: the labor theory of value. As Clune explains, neoliberalism has made that theory obsolete and with it, Marxist analysis. For Foucault there were several Marxisms in Marx.

What is the individual’s ongoing relation–how does she belong–to the national culture she may serve or criticize, but which has also helped shape her life and thought? This is the question embodied by Jasper Johns’s Flag. It has never been more relevant than in the new millennium–a political moment that is the backdrop to the themes of this book.