This essay traces the political development of black urban professionals and managers from the urban renewal era to the early period of federal devolution and privatization in the 1970s and 1980s. These periods are the foundation by which “generations” of black urban regimes have been generated. The staying power of black political entrepreneurs results from their capacity for populating, activating, and contracting black-led organizations in the nonprofit sector, which has allowed them to adjust to fiscal retrenchment and subsequent privatization. Black mayors have channeled demands for investment in public goods into contracts for black-led nonprofits and bootstrap social programs. In particular, the housing and community development field has allowed black political aspirants to cement ties to the real estate industry which plays an outsize role in postindustrial urban economies.

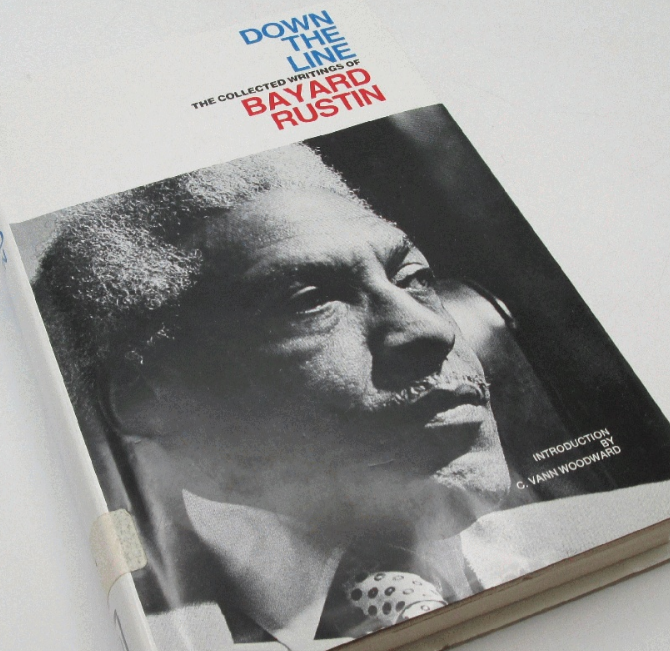

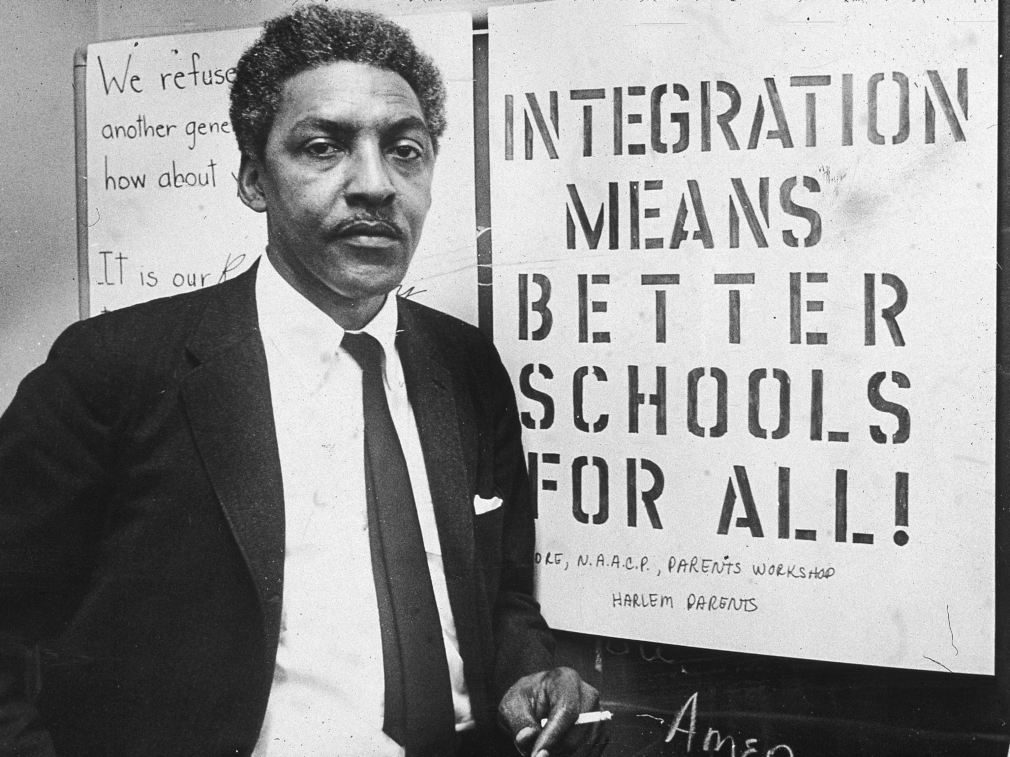

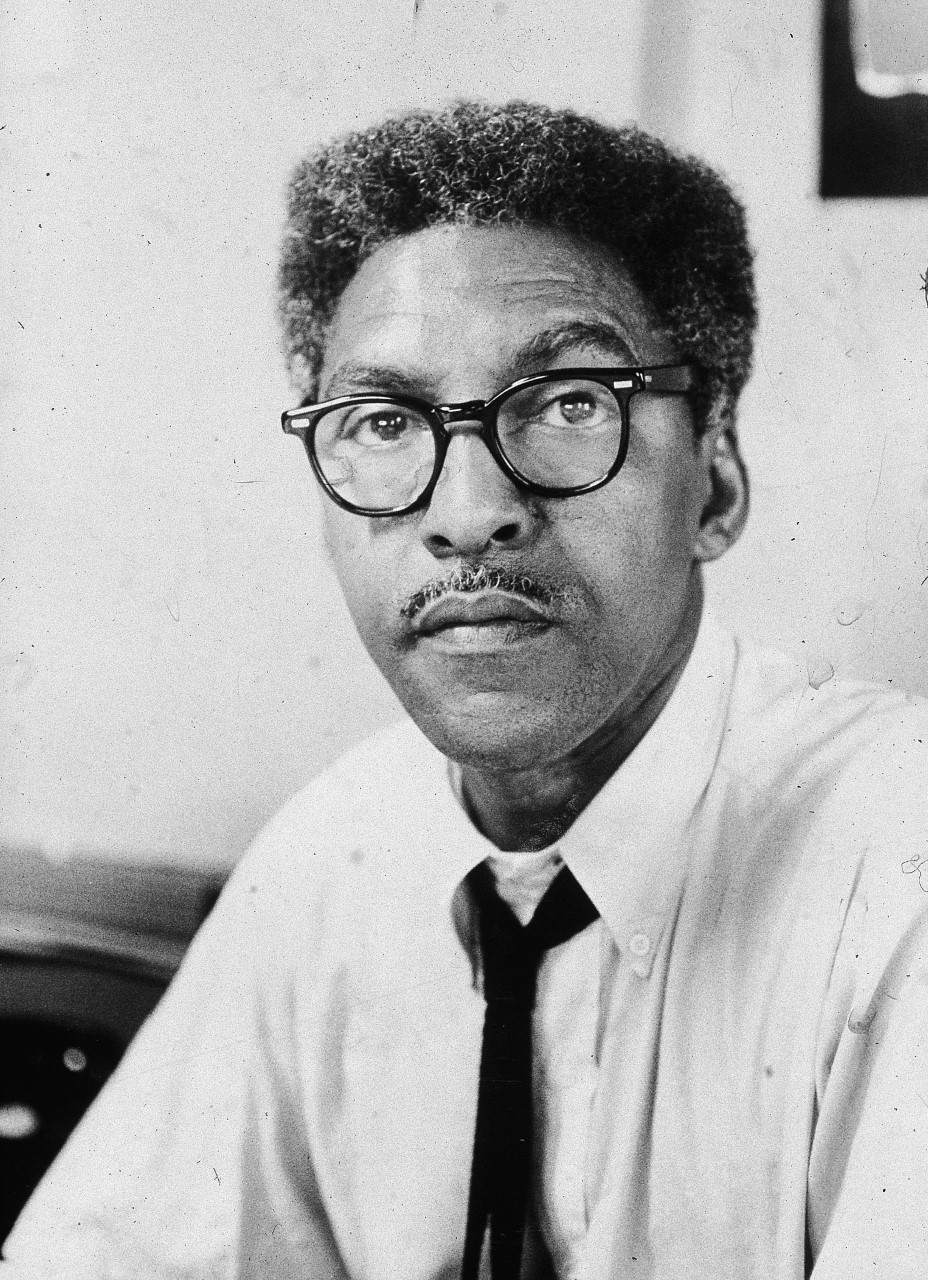

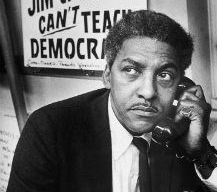

Rustin saw politics through a concrete, strategic lens, which provided a perspective that has become increasingly remote from both academic and activist experience. Indeed, as demonstrated in the essays selected here, he explicitly rejected the moralistic discourse that he saw undergirding much of Black Power and New Left politics, as well as the tendency to reduce the sources of inequality to psychologistic factors like prejudice, discrimination, or a generic racism.

Black capitalism is endorsed not only by Roy Innis of CORE but by President Nixon and various corporate interests. It does not cost much, and it leaves ghettos intact. The vast majority of black people, of course, are not capitalists and never will be, and they stand to lose from “buying black.” For black workers to define their problem primarily in terms of race is to ally themselves with white capitalists against white workers. It is the old strategy of Booker Washington in new guise. As Marcus Garvey put it, “The only convenient friend the Negro worker or laborer has in America at the present time is the white capitalist.”

The only way to really help the poor is to establish opportunities, as part of the total economic order, which in some way reflect the manner in which the poor immigrants gained a foothold in American society. It becomes tiresome to hear people who were very poor when they got here talk about how they lifted themselves by their bootstraps….Now they think they did, but they didn’t….I am for all kinds of educational programs. But education as we know it is not relevant to the fundamental problem of poverty. We must concentrate on providing people with opportunities to relate productively to the life of the society.

But the economic impact of black capitalism has been—and can only be—marginal at best, and if we are not careful, this approach may actually compound the injustices from which Negroes suffer. We must not forget that businesses are “in business” not to attack social injustice but to make a profit, and that the ghetto represents a poor market to invest in because of its poverty and deprivation.

I maintain that there are two elements in our society which can block Nixon’s strategy and they are the labor movement and the minorities, particularly the blacks. I, therefore, say to the young people in the Socialist League: You ought to recognize that economic progress is the basis for maintaining our coalition—that we are going to win because we emphasize, above all others, the economic issues in this society. Because there is no possibility for black people making progress if we emphasize only race. You can psychoanalyze every white person in the United States until he comes out pristine pure tomorrow morning, filled with love for black people—and that will not provide jobs for blacks or build housing. That is a political task which we must face.

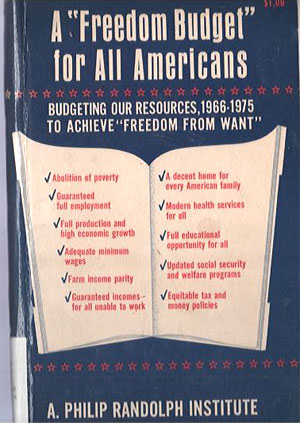

This society never has and never will do anything special for the Negro. That is the reason we call it the freedom budget for all Americans. It is not that I do not know that Negroes are most brutalized by poverty for they are! But I also know that 67 percent of the poor are white and unless we are going to draw up programs which have to do with the elimination of poverty and not concerned with Negro poverty we will not get anywhere in the society.

The close parallel between fin-de-siècle racist ideologues’ assertions of the primordial and immutable nature of white supremacy and contemporary race reductionists’ can provide perspective helpful for ascertaining what lies behind the impulse to insist, in the face of such overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that nothing has changed for black Americans and, yet more strikingly, Hartman’s dismissal of Emancipation as a “nonevent.”

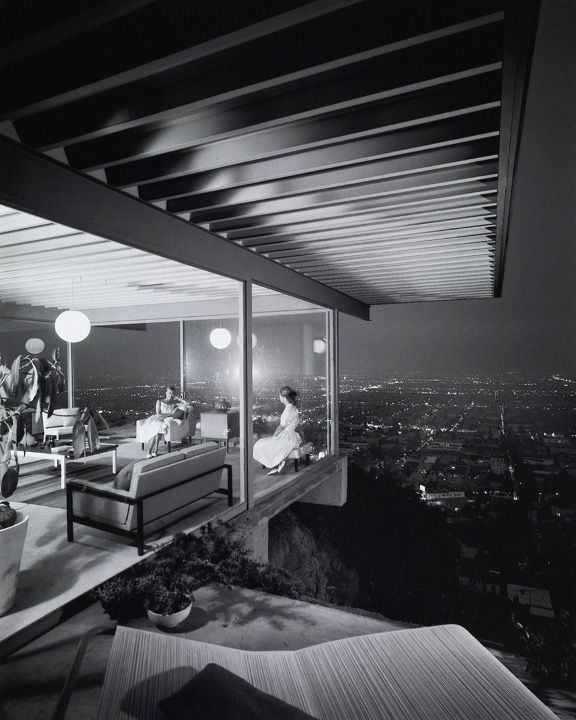

It is said, more or less correctly, that Mathsson brought the glashus (glass house) to Sweden after visiting Philip Johnson’s glass house in New Canaan in 1949. The following year he built his own furniture showroom, fully glazed on three sides, bringing a new world of transparency to the Nordic country. Within a few years he had mastered his own brand of glass architecture, a significant contribution to mid-century modernism. And he harbored a larger ambition. While Mathsson acknowledged Sweden’s cold temperatures and limited sun, he soon imagined a new utopia of glass: “I believe that the Swedish homes of the future will be a kind of greenhouse with tropical heat and a swimming pool, as pure opposition to our bad climate [dåliga klimat].”

Mid-twentieth century architecture reached a broad audience primarily through photographs, and photographers became essential early interpreters of the modern movement. In the United States, two major architectural photographers, Julius Shulman and Ezra Stoller, were known as innovators in the field, but a complete understanding of Shulman and Stoller requires addressing how they handled a defining artistic question of their time—the question of art and objecthood.