Was This Trip Really Necessary?

Suther’s goal is to establish new “methodological imperatives.” His way of going about it is characteristically inflationary in terms of proposing new notions, inventing new terminology, and redescribing life itself. But the real test for any new theory is not whether it can offer a structure of thought, but whether that structure has purchase on reality: that is, whether there are things that need to be conceived of in this way. On this front, Suther ultimately fails.

The Dead End of Intentionalism

The ordinary-language assumption that such metaphysical questions are resolved as soon as I raise my hand in a classroom or hug a friend when he tells me she has finally left him is given the lie by its own tacit metaphysics: a picture of reality as comprising two independent orders, one mechanical and complete in itself, the other normative and merely supervenient upon it. This is not a neutral description of our world, but a substantive—and historically specific—way of carving it up. By ordinary language’s own lights, moreover, the modern historical situation in which we experience ourselves as estranged from our own bodies, subject to economic mechanisms we do not control, generates a justified skepticism about the intentionality of our own bodily acts.

Reply to Suther and Bewes

Bewes’ commitment to the (Deleuzian) “cinematic apparatus”—replacing “the unity posited by a human action together with its motivations, causes, and intentions” with “a nondetermined, acentered and decentered perception”—involves the opposite of immanent purposiveness. The point of the wave poem was that you saw the marks on the beach as a poem because you saw in them the act of writing. But the point of Deleuzian immanence is “the rupture in the very relation between the image and action,” that is, between what you see and any action. The achievement of the cinema apparatus is not that it accomplishes the feat of embodying the intention in the work but that it accomplishes the feat of keeping the intention out of the work.

What if? A response to Walter Benn Michaels

What if Michaels, in some small part of himself and irrespective of what he maintains on the page, believes that this forty-year scholarly project might equally have been pursued not in the direction of an ever-expanding notion of intention but in the direction of an ever-diminishing one, a direction whose end would be its elimination altogether?

Issue #53: Normativity, AI, and Photographic Realism

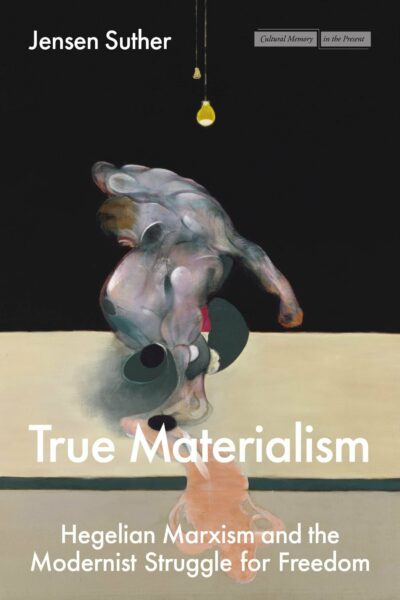

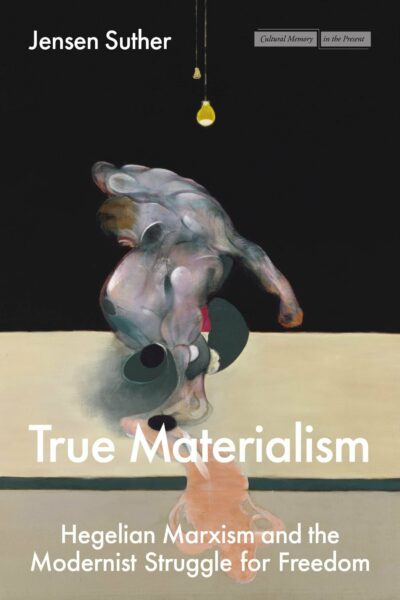

In this issue, Samuel C. Wheeler considers the status of design intention in LLMs, Walter Michaels and Pawel Kaczmarski discuss books by Jensen Suther and Timothy Bewes, Touré Reed is interviewed on “Black History from the Civil Rights Movement to BLM,” Vincent Hiscock discusses the function of idealization in socialist realist photography, and Michael Fried interviews Luc Delahaye.

Mystic Realism

During the Vietnam War, Allan Sekula sought to renovate social realism, a practice he associated with Lewis Hine, whom he called a “realist mystic.” Sekula objected to representations of social misery that make reference to religious iconography. Against Sekula, I argue that Hine’s practice illuminates the indispensability of idealizing means to political identification with or confrontation by a solidaristic “we.” The question remains: How to secure the benefit of a beatifying tradition of religious representation without world-transcending implications? How to produce an adequate social analysis without the dispassion of objectivity?

Not What a Lion Ought to Be

Even if we accept that all life “requires” survival and self-maintenance, it is still not clear why we should think about it in terms of purposes and forms. It is perfectly possible to say that living beings simply sustain themselves and reproduce, and once they no longer do, they cease to be alive. Conversely, something that does not do these things is simply not alive. A dead horse is not a failed live one. Unless, of course, we assume that it was trying to stay alive and failed. But in that case, we have already committed to intention as the source of normativity—that is what “trying and failing” means. Similarly, glaucoma may cause an eye to be unable to satisfy its function, but it is the function desired and imposed by its owner (who presumably intends to use their eye to see things). No notion of natural, biological form is necessary; either intention is present (and calls for interpretation), or it is not (and a causal account is all that is needed). The question of whether horses (or bacteria or trees) are capable of intentions is beside the point at the level of theory.

Action/intention/interpretation/ambition—Timothy Bewes and Jensen Suther

The worry that underlies the sense that both writers and readers can be irresponsible—the writer by failing to have the right relation to her intention, the reader by failing to attend to the writer’s attention—is incoherent. Everyone who produces a speech act produces a text that means what she means by it; everyone who reads one is understanding (or misunderstanding) what she meant by it. This is the force of the non-optional—the reason why intentionalism cannot be a choice—the reason, really, why there is no such thing as intentionalism.

Black History from the Civil Rights Movement to BLM

Constructs like “black-led movements,” the “black freedom movement,” or the “black radical tradition” often strip black life and politics of complexity and, of course, contingency by imagining that our positionality as oppressed people insulates black Americans—like no other human beings, ever—from all proximate cultural, economic, and political influences except for racism and sexism.

The bottom line, though, is that the political gains black Americans have made have always been the product of contingent, utilitarian, cross-racial political coalitions or agreements. This is among the reasons the scope of blacks’ conceptions of both inequality and equality, how blacks conceive the obstacles confronting them, what black Americans perceive to be social justice, along with the terrain on which the fight for a just society can and will be fought, are different depending on when and where you are talking about.

Does ChatGPT refer with Names? Design Intention and Derivative Reference in Large Language Models

Many writers discussing Artificial Intelligence argue that what a Large Language Model produces are not sentences with truth-values but rather “stochastic parrotings” that can be interpreted as true or false, but in the way that Daniel Webster interpreted the Old Man in the Mountain as a sculpture by God with a message for humanity. Steffen Koch has argued that names used by LLMs refer in virtue of Kripkean communication-chains, connecting their answers to the intended referents of names by people who made the posts in the training data. I argue that although an LLM’s uses of names are not connected to human communication chains, its outputs can nonetheless have meaning and truth-value by virtue of design-intentions of the programmers. In Millikan’s terms, an LLM has a proper function intended by its designers. It is designed to yield true sentences relevant to particular queries.