Issue #50: When Compromises Come Home to Roost

In this issue, Adolph Reed looks at a range of mid-century compromises that reshaped the nature of American politics; Touré Reed addresses the question of racial resentment in contemporary politics; José Arellano shows how the film Ex Machina figures the convergence of neoliberal economics and aesthetics; Pawel Kaczmarksi clarifies the role of Marxist notions of base and superstructure through a critique of Vivek Chibber’s writings; and Stephen Schryer critiques ecocritical readings of Richard Powers’s The Overstory as missing the point of the book’s critique of capital.

The Earth’s Intentions: Richard Powers’s The Overstory and the Limits of Anti-Anthropocentrism

Critics have celebrated Richard Powers’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Overstory (2018), for the way that it distills key ecocritical ideas that gained traction in the humanities in the 2010s. Echoing New Materialists’ insistence that we set aside subject-centered ontologies that reduce non-humans to an instrumental status, the novel endows trees with agency, even granting them the ability to speak in a language that human beings might learn to understand. This essay pushes back against this desire for deep ecology, arguing that it short-circuits the novel’s critique of global capitalism. Drawing on a Transcendentalist model of language, Powers’s novel imagines trees using natural signs that collapse signs and referents, allowing them to directly change the chemistry of human brains. This fantasy of mind control distracts from the novel’s investment in communicative action, marked by recurring scenes of reading and persuasion.

Looking Backward to Counter Mysticism and Despair

Because even structuralists like Reuther and Charles Killingsworth shared with the Keynesians the viewpoint that interests of capital and labor were harmonizable and that economic problems were therefore fundamentally technical, the deeper political significance of the differences went unnoticed, or at least unremarked upon. The effect was to obscure the systemic roots of economic inequality in American capitalism, in fact eventually to render it invisible as inequality.

Robotic Pollocks in the Age of Amazon: Ex Machina, Actions, and Mechanical Art

Ex Machina helps make visible the effects of the technologically enabled economy that led to the historical convergence of theories of art and action that today appear as the stuff of common sense. The problem the movie presents is less about empathy for the other than it is about a society structured by an economy wherein the concept of intention no longer obtains. Ex Machina thus prompts viewers to consider the political significance of creating and interpreting a work of art today.

Blinded by Righteous Outrage: From the 1994 Crime Act to Trump 2.0

From the 1994 Crime Act through to the re-election of Donald Trump, liberal thought shapers and policymakers have tended to draw upon a moral righteousness that uncouples racial disparities from the material contexts that engender them, thereby obscuring neoliberalism’s inability to deliver for poor and working-class Americans—blacks being overrepresented among them. As the Trump administration aggressively moves to dismantle the gains that African Americans and other non-whites have made since the Civil Rights Movement if not Reconstruction, progressives should take seriously the counterproductive implications of a righteous, groupist social justice discourse that mistakes sermonizing for analysis while treating “races” as epigenetic identities (rather than ascriptive categories) with discrete interests.

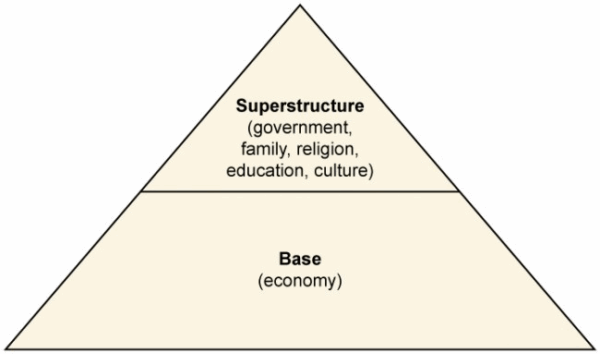

Marxism and the Good Picture of Intention

No class analysis, no matter how precise or exhaustive, will provide the answers of the kind Chibber requires, and to invoke causal factors other than class only delays the issue, as no collection of causal accounts will ever account for all of the existing meanings because interpretation cannot be reduced to a causal account and meaning cannot be reduced to a sum of the work’s causes. Insofar as intention is not simply contained in the mind, no account of how it came to be may replace the interpretation of a meaningful totality of which it is part.

Revisiting Race, Politics, and Culture: A Symposium

Scholarship and popular memory has far too often taken on the role of hagiography or sought a pure and true 1960s spirit, “uncaptured” by elites and reflective of real, authentic radicalism. Rather than being critically analyzed as key nodes of causation in the defeat of an effective egalitarian politics and the subsequent turn toward reaction—as the contributors to Race, Politics, and Culture do, befitting the seriousness with which they took their charge as both scholars and political actors—the worst tendencies of sixties-era social movements are now almost religiously worshipped in nominally left organizing and thought.

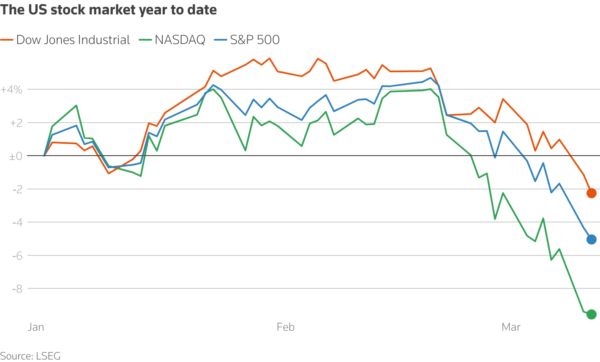

The Man Who Would Be King: Method in Trump’s Madness, Contradictions in Trump’s Method

Trump can meet the expectations of those looking for a hard line on immigration and can grant his corporate backers the tax cuts and deregulation they greedily seek. But it is the economy that will be decisive for his populist base, and on this measure, Trump is very unlikely to succeed. As for the business elite, they have always assumed Trump was not so mad as to start a tariff war that risked undermining the American empire itself. As that danger materializes, business will rebel. The question will then shift from what Trump intends to do to what he will he do as his plans go astray.

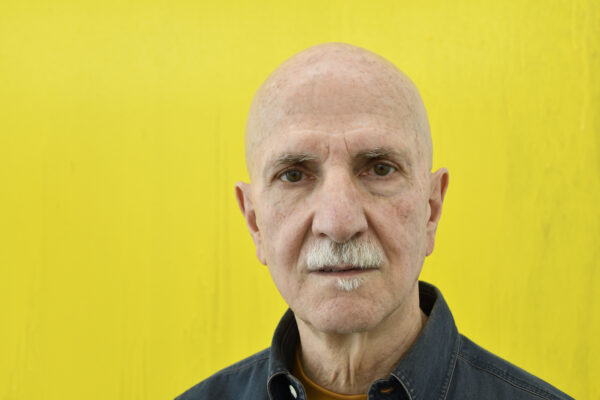

Issue #49: Portraits of Divided Light: In Memory of Joseph Marioni (1943-2024)

In memory of the radical ambition and extraordinary achievement of the painter Joseph Marioni, this issue brings together four contributions in four different forms: poems by Michael Fried, photographs by James Welling, a film by Joe De Francesco, and an essay by Joseph Staten.

Painter: Making A Modern Painting

With generous permission

from the filmmaker’s estate,

we are honored to share

this extraordinary short

documentary, completed in

2017 by Joseph De

Francesco with Michael

O’Connell. Framed as an

intimate interview with

Marioni, it also contains the

only known footage of him

painting.