Lukács/Fried

After 1848 the bourgeoisie cannot and no longer does understand itself as standing in for the universal. The threat posed to “subjective but universal” judgment by the newly insistent particularity of the literal, empirical bourgeois audience becomes a problem to be — sometimes literally — confronted.

John Berger, Michael Fried and Contemporary Art

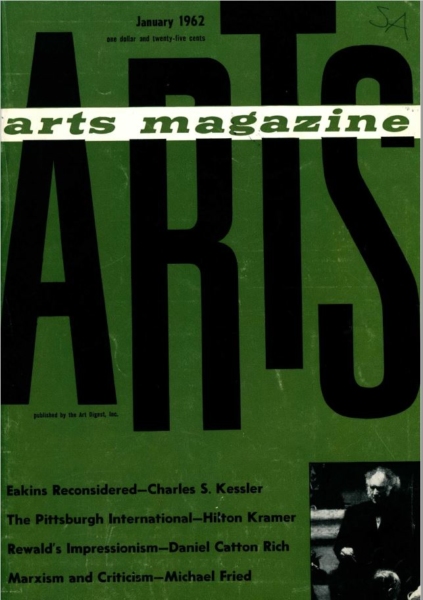

John Berger and Michael Fried emerged as forceful critics alongside, and largely against, the new form of art that we now call “contemporary.” To fully appreciate what was and continues to be at stake in the distinction between their competing critical arguments at the time of Fried’s January 1962 review of Berger’s 1960 book Permanent Red, we need to understand all three of our terms—Berger, Fried and contemporary art—in relation to the ruins of modern art atop of which each staked its claim for the future.

Some Comments on the Claims Made For and Against Painting

Experiences of world-disclosure are accomplished by achievements in certain long-tested forms of art—what we can call the canonical forms. These forms, like easel painting or lyric poetry, have proven over long periods of time to be the appropriate sites for this activity; but, more than that, they were practices through which the value of world-disclosure had been invented and developed through history. It was on this basis that they constituted a canon not just of exemplary works in each art, but a canon of the forms of art themselves. As such, they embodied criteria that could be effective in deciding if an activity was or was not “art.” Although the existence of the canon gave no conceptual guarantee or definition of art, it was accepted as one, de facto, based on its own history, or histories.

Marxism and Criticism

What all this comes down to, then, is that Berger accepts a priori a militant and often staggeringly vulgarized brand of Marxism from which all his judgments about art derive, in language anyway. … My fundamental objection is not that Berger begins from a position of accepting Marxist theory. In the world we live in more and more critics of art may be expected to start from similar political premises. But what is imperative is that the critic define his terms; that he show with sensitivity and logical rigor the usefulness and, if possible, the necessity of employing Marxist concepts and terminology. Unless he can do this his judgments will reveal nothing more

than the strength of his bias and the slovenliness of his mind: they can say nothing about the works of art in question.

Art as Seeing Through Neoliberal De-reification

The individualization of artworks was due to the ubiquity of formalist art and criticism, a sign, in Berger’s view, that art had been intimidated by the barrier between avant-garde art and the working class. This situation posits for Berger a challenge to be overcome to deliver new ways of seeing, breaking through subjective private worlds and toward democratic and collective ways of seeing.

Daguerre, Christian Prometheus

Who was Daguerre? The person who precipitated the fall of man into foul narcissism? Or the person who, by giving men mastery of divine light, offered them a path toward ultimate redemption? For his part, Daguerre seemed to be quite conscious of renewing Prometheus’s ancient feat, drawing upon it with evident pride.

Ruskin’s Broken Middle

Whenever Ruskin’s language steers toward the performative, it stages its own inability to perform. Instead emerges the quieter power of Ruskin’s constative mode—its gentle, unpossessive efficacy. Out of this come new possibilities for descriptive relation. Neither quite active or passive, the attention Ruskin’s descriptions perform might achieve a voice in some radical sense “middle,” inhabiting, however provisionally, some self-reflexive space between.

William Morris: The Poetics of Indigo Discharge Printing

Morris was thinking of the chemical events in indigo discharge printing as analogous to the actions of human history. […] The material processes of getting the dye into the fabric are correlated by him to the politics of the world’s struggles and the prospects for a future society.

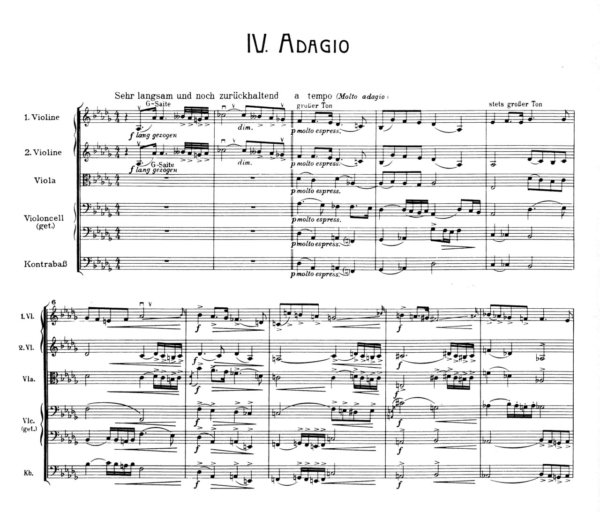

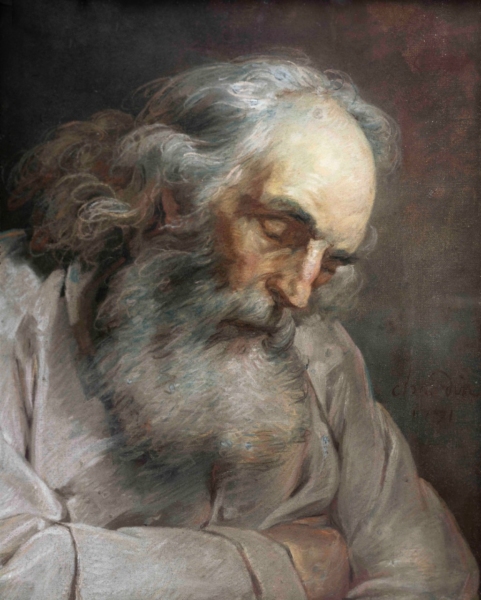

Chardin’s Pastels

In this essay I want to recover not only the academic controversy surrounding the balance between real and ideal, the beau idéal and the beau réel, but also the significance of an empiricist recasting of the role of perception in cognition and its justifiability as the necessary grounds for invention.

Issue #34: Deneocolonizing?

Essays on the current state of politics in Brazil, Racial ideology in the NFL, and the prospects of Deneocolonizing the University.