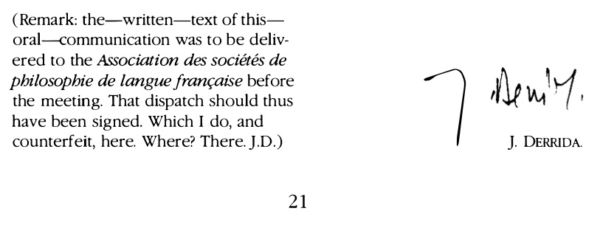

Issue #45: Derrida’s “Signature Event Context”: The Next Fifty Years?

“Signature Event Context” has proved to be Derrida’s most enduring essay. New fields have been founded on its basis, and it is his only work to address at length a text by a philosopher not from the Continental tradition. Occasioned by the passing of “Signature’s” fiftieth anniversary, the present issue, edited by Joshua Kates, includes essays from scholars with a range of sympathies to Derrida’s project. Their articles focus less on purely scholarly concerns and instead on the truth about questions raised by Derrida’s essay: of textual identity, the role of intention and citation, the status of fictional and historical discourses, and the work of interpretation. A series of interchanges between Walter Benn Michaels, Henry Staten, and Joshua Kates, commenting on Michaels’s essay, are also included, which pursue further this attempt to get at the things themselves.

A Davidsonian version of Dissemination and Abandonment

Speech and writing actions differ from their products. We can call the actions utterings and inscribings. An uttering’s product is an utterance. An inscribing’s product is an inscription. An uttering or inscribing is “abandoned” because features of the uttering or inscribing are not linguistically available to the audience in the utterance or inscription. Iterations of what is linguistically available, whether by the speaker or others, differ in truth-conditions from the original simply because the present and past tenses are indexicals. The force of an original is not linguistically available, so every utterance or inscription is “abandoned.” Repetitions of utterances with indexicals generate expressions with different truth-conditions but may be copies, and so iterations.

Interchange II: Closing Remarks

Another way to get at this is just to say that the identification of what the text means with what the author intends is already in place without our having any recourse to a theory of intention or to a positive account of intention as a mental state. While the work that it does in place—determining the act—makes clear the mistake in imagining that the text we write could be either controlled by or liberated from what we meant.

Interchange I: On intention, context, and meaning, with examples

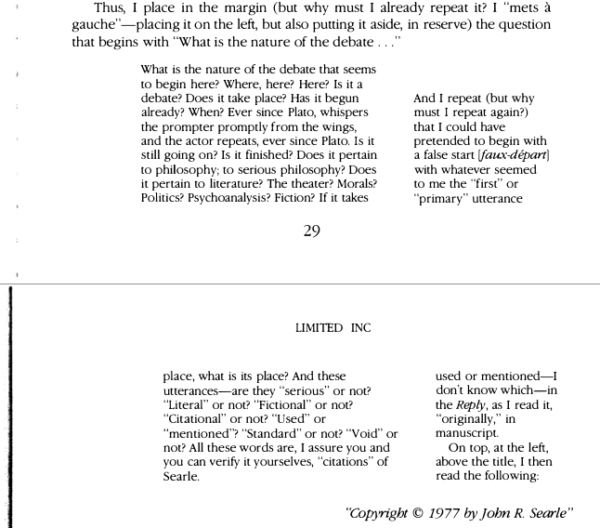

The reason Derrida does not think intentions are governing is because he thinks the condition of having a (linguistic or semiotic) one entails a form of repeatability that the intention cannot fully master. Yet there also cannot be any text-y things, written or spoken or semiotic, without intention playing some role. Moreover, as an interpreter, Derrida wants both: he wants to interpret faithfully the intention, as Henry pointed out, and read what is not available as an intention but inscribed in a text (which reading also produces). Not one or the other, but both.

Produced and Abandoned: Action and Intention in Derrida

The problem, as we’ve already begun to see, is that once you’re committed to the idea that meaning is something you try to control and/or that it’s something you impose, you’re committed also to an account of the text in which the intention must be (what Derrida rightly denies it can be) outside of it. Indeed, this is exactly what the reduction of the text to the mark requires since the act of writing is here conceived as the writer’s effort to impose a meaning on the mark she has made and since the act of reading involves the impositions of other meanings, which need not be the same as the writer’s. The reason the mark is abandoned is because that imposition necessarily fails, leaving a remainder that remains necessarily “open.”

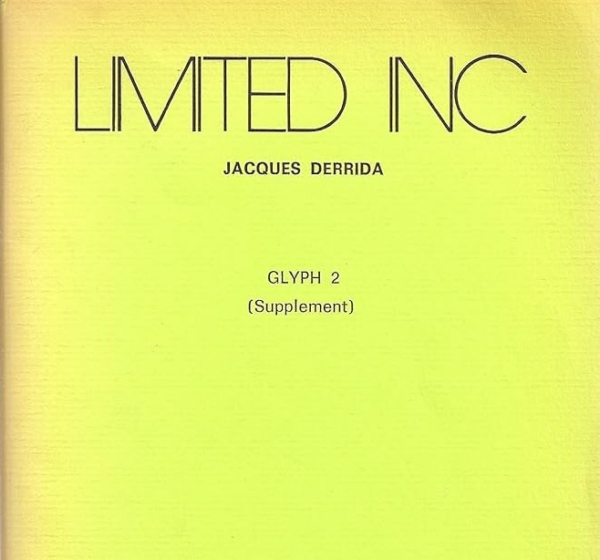

Corporate Communiqué: The Derrida-Holmes Merger

I want to argue that Derrida’s provocative invocation of a corporation reveals certain premises that deconstruction shares with the corporate legal form, and that both mistakenly assume—in their theorizing—that intentions are causes. More specifically, Derrida’s picture of communication was already, for late-nineteenth-century legal theorists, their problem of corporate intention. How should people understand what is happening when they negotiate with vast collective social agents whose intentions seem unreliable or unknowable?

“Signature Event Context” and The Possibility of History

How is history, as a discipline and a practice of writing, possible? “What happens in this case, what is transmitted or communicated,” Derrida argues, “are not phenomena of meaning or signification” (SEC, 309). If we are trying to communicate with or, more importantly, to listen to this distant past, there are traces or fragments of the past that resist immediate significance or comprehensible meaning but are still telling us something of historical value. It is from these traces that we write history.

Performative Contexts

Is all this to say that we should give up on context because we can have no purchase on it? I think it is rather a way of pointing to the constitutively incomplete nature of what is still the necessary task of making sense of texts in context. For every context that fails to determine its text completely because it, itself, is structurally indeterminate, new contexts come to impose their force and their relevance. The flip side of Derrida’s claim that every text ruptures with its context is his assertion that texts are citable and reinscribable in other contexts, for belonging to the structure of every mark is both “the possibility of disengagement and citational graft.”

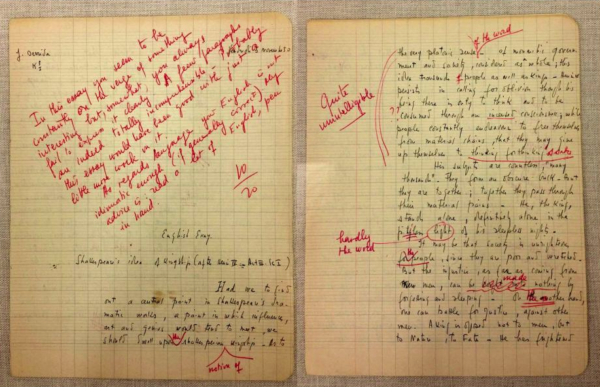

Write, Rinse, Repeat: Text and Context in Derrida’s SEC and in Literary Studies

None of what the text says and is about can be determined beginning from such considerations, however; texts are not functions of cultural, social, or historical “structures” or “logics.” Such suppositions erase the text itself, by subordinating it to new and again unexplained systems or structures, implicitly resurrecting the ideal. Appeals to structures or logics necessarily trade on otherwise unexplained ideal last instances, ones hailing now not from language but from society, history, the economy, and so on. Their invocation thus renders the text in question effectively equivalent to the common understanding of “now is night,” an inscription somehow without a writer, receiver or context—subordinating it to a new ideal instance and thereby depriving it of its status as an authored text.

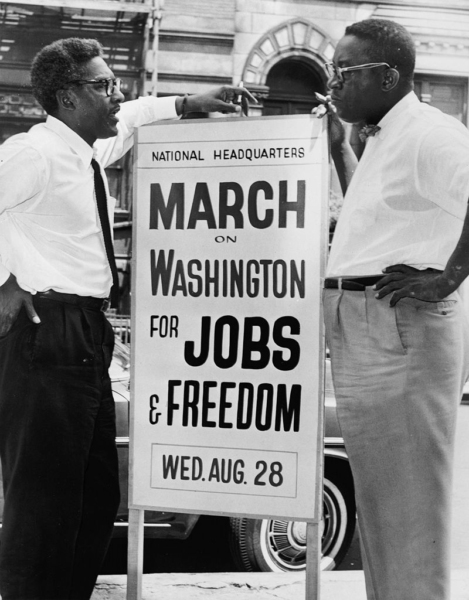

The Obamas’ “Rustin”: Fun Tricks You Can Do on the Past

The project of “reclamation and celebration” proceeds from a common impulse to rediscover/invent black Greats who by force of their own will make “change” or “contributions.” In Ava Duvernay’s Selma Martin Luther King, Jr. shows up and exudes a beatific glow that makes things happen. These films and filmmakers have no clue how movements are reproduced as mass projects, from the bottom up and top down, in a trajectory plotted by continuously improvised response to and anticipation of layers of internal and external pressures. But that’s not their point. Rustin isn’t interested in illuminating the intricacies of the civil rights movement; it wants us to recognize its subject’s place in a pantheon of black and American Greats.