Picasso (and Warhol) and Things

The combination of flatness, enframing, and the implied interchangeability of consumer goods that we see in Warhol’s Soup Cans is both characteristic and telling. In front of such works, I can only think of what the philosopher Martin Heidegger referred to as the “standing reserve.” Insofar as our present sense of reality is shaped by the technological age in which we live, we increasingly treat all entities, Heidegger claimed, as intrinsically meaningless “resources,” a “reserve” standing by merely to be optimized and ordered for maximally flexible use.

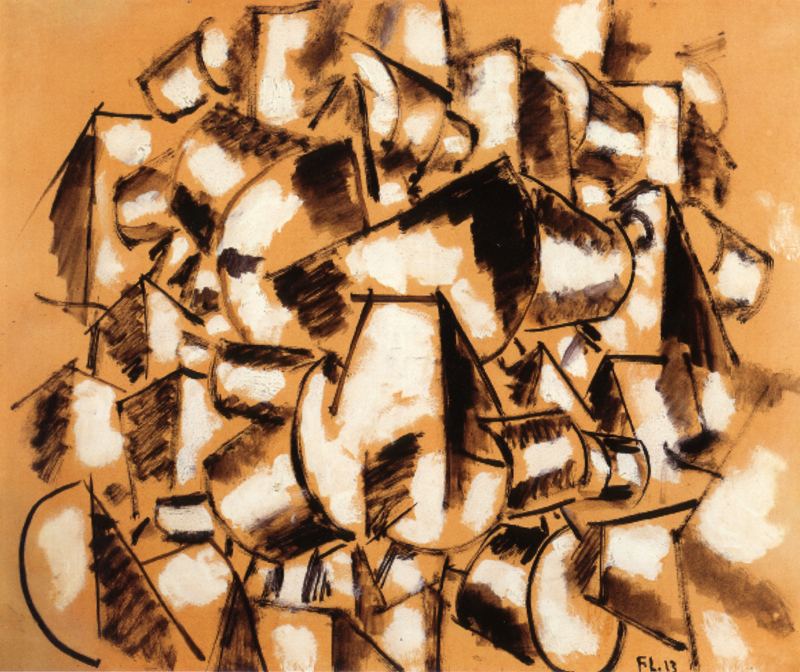

“The Painter’s Revenge”: Fernand Léger For and Against Cinema

In the case of Ballet mécanique, however, it is no longer a question of competing with or dominating spectacular vision from within painting. Opting for a different strategy, Léger works against cinematic absorption and the pseudo-intensity of cinema from within cinema itself.

Pollock’s Formalist Spaces

There is a deep schism within Pollock criticism. Taking Pollock’s marks to index the artist’s activity elevates the causes of his paintings over their meanings, with the consequence that his works of art are reduced to intentionless surfaces that just register his “traces.” That position implicitly requires us to reject the status of a painting as a medium of expression, and treat it instead as an occasion for a viewer’s experience. But Pollock’s project–one that finds its most rigorous articulation in formalist accounts of his art–is based on demarcating the actual from the representational, the literal surface from pictorial meaning.

The Conditions of Interpretation: A Reception History of The Synagogue by Max Beckmann

When Max Beckmann (1884-1950) painted The Synagogue in 1919, he could not have anticipated the ways in which it would come to be viewed and interpreted. His critics were the first to weigh in after World War I with poetic analyses. Subsequent viewers – including museum and municipal officials – placed less emphasis on the painting’s purely formal values. Since 1945, The Synagogue’s prophetic quality and historical function as well as its political uses and pedagogical applications have shaped its reception. Eschewing an interpretive mastery of the painting, this essay considers the viewer’s varied response to Beckmann’s picture as evidence of its radical authenticity.

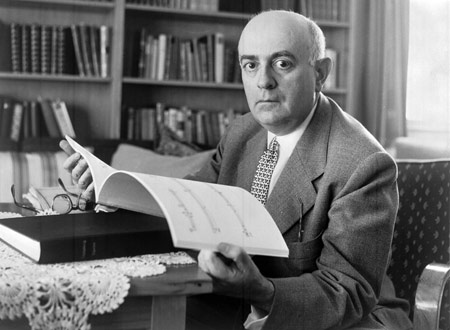

Do We Need Adorno?

In one of his last interviews Michel Foucault famously said “As far as I’m concerned, Marx doesn’t exist.” What he meant was that “Marx” as an author was something largely fabricated from concepts borrowed from the eighteenth century, in particular the writings of David Ricardo. From Ricardo he derived his most crucial idea: the labor theory of value. As Clune explains, neoliberalism has made that theory obsolete and with it, Marxist analysis. For Foucault there were several Marxisms in Marx.

A House Divided: American Art since 1955

What is the individual’s ongoing relation–how does she belong–to the national culture she may serve or criticize, but which has also helped shape her life and thought? This is the question embodied by Jasper Johns’s Flag. It has never been more relevant than in the new millennium–a political moment that is the backdrop to the themes of this book.

Intention and Interpretation

This issue is loosely the result of a double session on Intention and Interpretation at the College Art Association meeting of February 2010. (The original call for papers appears below.) The line-up of speakers was somewhat different from the authors of this special issue, but these remarks describe the developments to which both sets of […]

Engendering Pliage: Simon Hantaï’s Meuns

Like Lacan’s woman, painting for Hantaï comes to be defined by its condition of pas-tout, “not-all.”

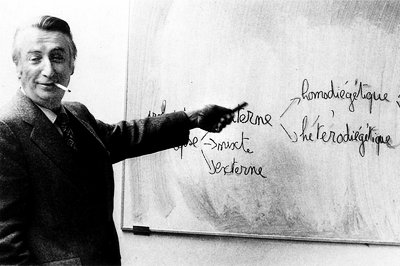

Introduction: Intention and Interpretation

One now routinely reads rote refusals of intentional interpretation and insouciant claims for the spectator’s prerogative in making meaning. Such refusals and claims may be right—that’s a question we may discuss today—, but their reexamination, which is to say this conversation, is overdue.

Intentionality and Art Historical Methodology: A Case Study

It is, typically, an aesthetic intuition. Aesthetic intuitions are first of all intuitions, in the everyday sense of hunch, in the psychological sense of an act of perception, and in the philosophical sense of an act of the imagination. What characterizes them not just as intuitions but as aesthetic is that they share with aesthetic experience their subjective, affective, non-conceptual nature, and with aesthetic judgments their reflexivity and their claim to universal validity, most often expressed as a claim to reflect factual truth.