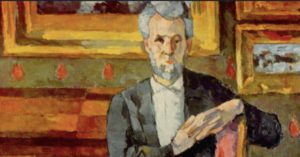

Cézanne’s Sensations

All of Cézanne’s “theory” seems to come down to what he calls “realization,” an operation of conversion that he was the first modern painter to attempt. Critics had a premonition of it, condemning his “too exclusive love of yellow” and warning the public: “If you visit the exhibition with a woman in an interesting position, pass quickly by the portrait of a man by Mr. Cézanne… That strange-looking head, the color of boot cuffs, could make too vivid an impression on her and give her fruit yellow fever before its entry into the world.”