Which suggests not only that it would be puzzling for a critical practice to declare itself against affect but that it’s equally puzzling to think of any critical practice as being for affect—to think, for example, of “reading for mood” as “a mode of reading.” There are no such things as modes of reading—there’s only trying to understand what a text is doing.

The trivial truth is that what they mean by challenging the operation of capitalist markets (i.e. massive downward redistribution) would indeed reduce racialized poverty, for the obvious reason that (as Adolph and I and millions of others keep on tiresomely repeating) precisely because black people are disproportionately poor all efforts of redistribution will disproportionately benefit them. The totally false idea is that a challenge to racial disparities gets you out from under what Reed calls “neoliberalism’s logic.” In fact, unlocking inherited inequality (racialized or not) and achieving real equality of opportunity (hence more upward mobility) is left neoliberalism’s wet dream.

The Anscombian response to this worry is that it’s a mistake to break the act down into component parts, a mistake to think of the intention as something that’s outside of the physical act, either as its cause or as a mental state existing either prior to or alongside it. That’s why she says your hug isn’t given its meaning by the words “you silly little twit” “occur[ring]” to you while you embrace your old acquaintance, they have to be “seriously meant.” And you could mean the hug to be ironic even if you were thinking only affectionate thoughts at the time you administered it, or thinking nothing at all. The correct answer to the question, “why did you hug him?” would still be, to show my contempt.

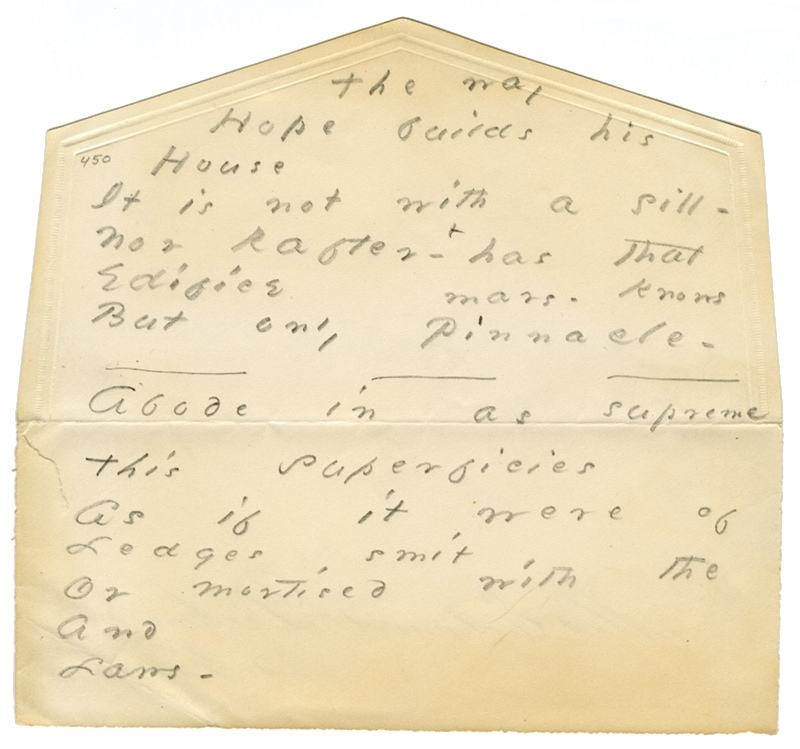

So there is a sense in which Winogrand’s personal crisis expresses a theoretical position, just as there’s an equally important sense in which that theoretical position and the alternatives to it (what it might mean to intend something, and especially what it might mean not to or what it might mean for your reasons to be treated as causes) were becoming at the time of that crisis central to literary theory and aesthetic production. Indeed, in what is now an aesthetic and a political as much as a philosophical sense, the structure of intentional action has recently emerged as a crucial issue.

This doesn’t mean that gay marriage isn’t a good thing, and it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be vigilant in fighting all kinds of discrimination. It just means that fighting discrimination has nothing to do with fighting economic inequality, and that the commitment to identity politics has been more an expression of our enthusiasm for the free market than a form of resistance to it. You can, for example, be a feminist committed to equal pay for men and women and also be committed to equality between management and labor but, as the example of everyone who’s ever campaigned against the glass ceiling shows, you don’t have to be and aren’t likely to be.

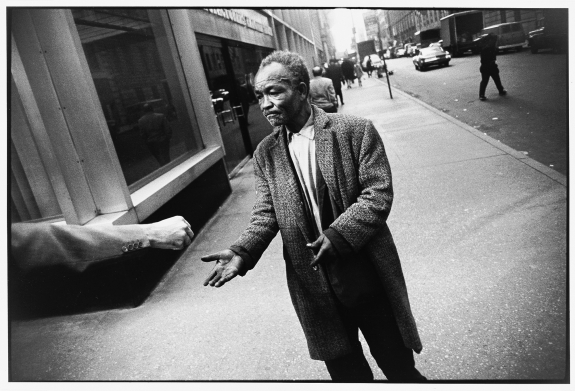

Another way of putting this is to say that the violence of the frame consists above all in making our lives as irrelevant as hers, and it’s in this indifference to our particularity (this allegorizing of its irrelevance) that I locate the politics of Kydd’s work.

It will, I want to argue, be hard to describe Owen Kydd’s practice as appealing to the plurality of the medium against Art; on the contrary, it will be better understood as doing just the opposite, as redeploying the idea of the medium precisely on behalf of the idea of Art—and against a pluralism that is not only aesthetic but political.

…if we wanted the unrich to stop being such a (vastly) underrepresented minority in our universities, we’d have to throw most of our current students out. From this standpoint, the most effective version of an occupy movement on campuses like Michigan’s would be one in which the students stopped occupying it and made way for not the 99% but the 75% who have been systematically denied admission.

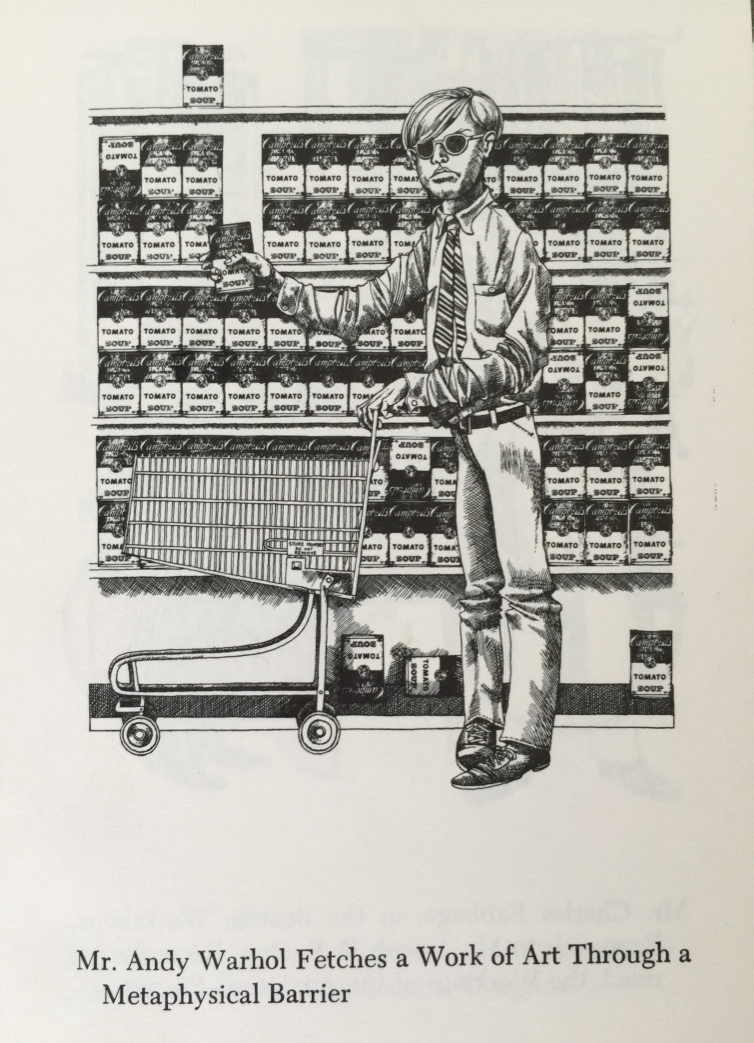

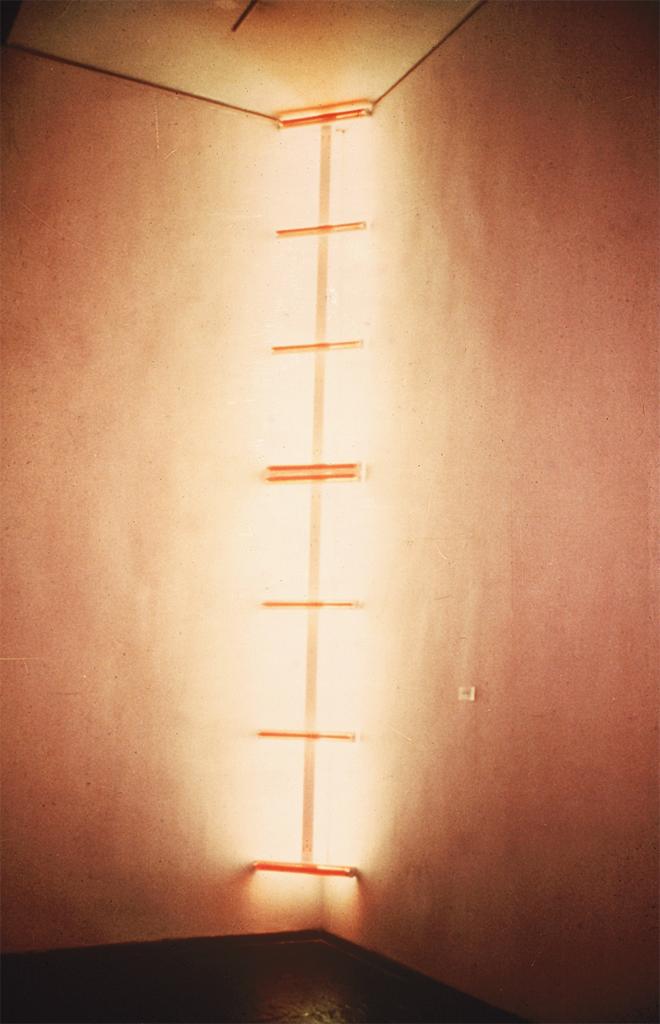

All fluorescent bulbs will eventually go out; only Flavin’s intentions can make some of them also be about the fact that they will eventually go out. All of us may think of the ephemeral when we look at a fluorescent bulb flickering; only the belief that this (or something else) is what Flavin meant us to think turns our responses into interpretations.

What I’ve been calling the work’s performance is nothing other than the causal account of its production, the kind of account you can give for any work of art. The difference is just that Chang has folded the process through which the work was produced into the experience of seeing it. This is a difference that matters.