Two Poems

In the office park he spoke of the land.

To the loan officer, of the land.

At the temp agency, the land.

Issue #23: Naturalizing Class Relations

In this issue we address the various ways in which class has been naturalized by popular political alternatives. As Warren, Reed, Legette, and Michaels argue, there is a class politics to antiracism, which has been mostly expunged from public debate. Grasso considers the rehabilitative ideology of the prison system, Sowa the stakes of the new populism. Finally, Cronan and Palermo look at a current variant of neoliberalism in art history.

Tain’t So

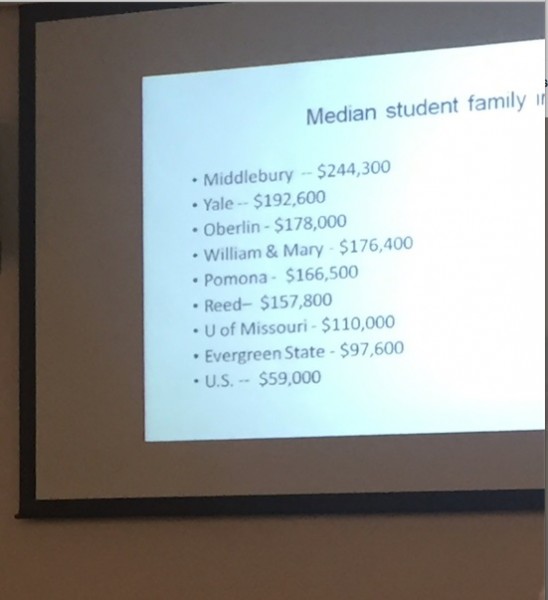

To lay out, as clearly and as programmatically as we could, the reasons why despite protestations to the contrary, antiracism, understood as insisting on the symmetry of fighting discrimination and fighting exploitation, suppresses the development of a working class politics rather than offering a road to it. To make this point, the essays printed here, perhaps a little more insistently than our previous responses to critics, attend to the way that antiracism is an expression of the class position of those of us who produce the bulk of the commentary on injustice, and who routinely confront race and gender disparities in our everyday lives.

Black Politics After 2016

Largely because of the challenge posed by the alternative political vision that Sanders advanced and the subsequent struggle over how to interpret the meanings of Trump’s victory, the 2016 election and its aftermath have thrown into relief the extent to which antiracism, and other formulations of politics based on ascriptive identities, are not simply alternatives to a (working) class politics, as Clinton’s cheesy put-down during the campaign implied. What is typically called identity politics reflects the perspective of a different class, the professional and managerial strata who are relatively insulated from the negative impacts of the four decades long regime of regressive redistribution and better positioned to take advantage of the opportunity structures it opens. That perspective suggests a reason many high-profile antiracists have become so vehement in their opposition to a politics centered on downward economic redistribution.

The Political Economy of Anti-Racism

This is why some of us have been arguing that identity politics is not an alternative to class politics but a form of it: it’s the politics of an upper class that has no problem with seeing people left behind as long as they haven’t been left behind because of their race or sex. And (this is at least one of the things that Marx meant by ideology) it’s promulgated not only by people who understand themselves as advocates of capital but by many who don’t.

The Unity of Individualism and Determinism in the Rehabilitative Ideal

In recent years, political debates over American crime policy have become centered on whether prisons should aim to rehabilitate rather than punish offenders. While rehabilitative discourse appears to be a progressive alternative to punitive politics, I argue that rehabilitative ideology is built on theoretical premises that justify punitive politics. By conceptualizing criminality within individualistic and deterministic frameworks, the rehabilitative ideal of American criminal justice depicts crime as a function of individual-level faults rather than as symptoms of the deeper social and political inequalities that shape the class profile of the prison population. When criminality is viewed as a function of defects and deficiencies entirely rooted in the person, criminality can only be cured through individual level responses rather than more systematic structural reform.

The Role of Race in Contemporary U. S. Politics: V.O. Key’s Enduring Insight

Today, race performs the function of suppressing working-class politics in the interests of both white and black political elites who are equally committed to capitalist class priorities as defining the boundary of political possibility.

Populism or Capitalist De-modernization at the Semi-periphery: The Case of Poland

It’s here again, that we encounter the basic flaw of liberal common sense, with its fixation on cultural factors and the importance of ethos. What they neglect is an element that was entirely wiped out of both public and academic discourse in Poland as well as elsewhere, for example, in the US: the issue of class and its indelible materialist component. Populism is a kind of displaced and perverted class revolt. It derives from an oppression of double kind: material for the poor and symbolic for the lower-middle class.

More Neoliberal Art History: Pamela Lee’s Mid-Century Modern

That individual experience is what is at stake in an analysis like Lee’s and in projects like the Multinode Metagame and the Opsroom installation means that they are always different, always changing, always occasioning new “meanings.” This is the polysemic, and the polysemic is not the opposition, but the alibi of neoliberalism. It provides cover for exploitation, the glitter of a thousand stars to transfix the thousands of victims while their pockets are being picked.

What I Really Mean

Deposit doesn’t mean cash. I mean the layer of ash

Distributed equally on both my palms.