Mazzocchi and the Moment

The most immediate challenge we face now is to prepare for what is going to be the political equivalent of a street fight that we’ll have to wage between now and at least 2018 just to preserve space for getting onto the offensive against the horrors likely to come at us from Trump, the Republican congress, and random Brown Shirt elements Trump’s victory has emboldened. At the same time, however, we need to reflect on the extent to which progressive practice has absorbed the ideological premises of left-neoliberalism.

Listening to Trump

Contrary to how he was portrayed in the mainstream media Trump did not talk only of walls, immigration bans, and deportations. In fact he usually didn’t spend much time on those themes. Don’t get me wrong, Trump is a racist, misogynist, and confessed sexual predator who has legitimized dangerous street-level hate and his administration will almost certainly be a terrible new low in the evolution of American authoritarianism. But the heart of his message was something different, an ersatz economic populism that spoke directly, clearly and emotionally to legitimate working class concerns.

Splendors and Miseries of the Antiracist “Left”

Proliferation of this Kabuki theater politics among leftists stems in part from the dialectic of desperation and wishful thinking that underlies the cargo-cult tendency; it is commonly driven by an understandable sense of urgency that the dangers facing us are so grave as to require some immediate action in response. That dialectic encourages immediatist fantasies as well as tendencies to define the direct goal of political action as exposing, or bearing witness against, injustice.

A Note from “His Collaborator”

The trivial truth is that what they mean by challenging the operation of capitalist markets (i.e. massive downward redistribution) would indeed reduce racialized poverty, for the obvious reason that (as Adolph and I and millions of others keep on tiresomely repeating) precisely because black people are disproportionately poor all efforts of redistribution will disproportionately benefit them. The totally false idea is that a challenge to racial disparities gets you out from under what Reed calls “neoliberalism’s logic.” In fact, unlocking inherited inequality (racialized or not) and achieving real equality of opportunity (hence more upward mobility) is left neoliberalism’s wet dream.

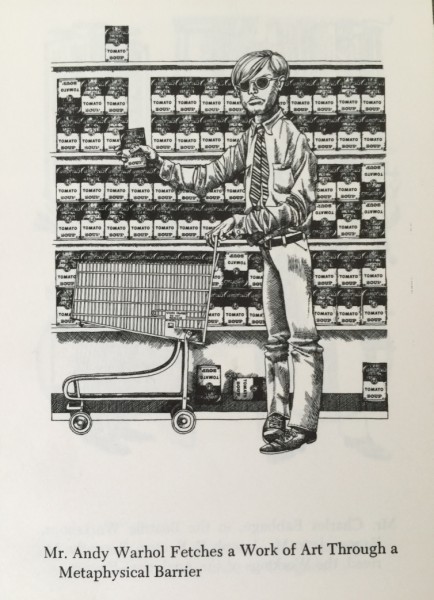

Anscombe and Winogrand, Danto and Mapplethorpe: A Reply to Dominic McIver Lopes

The Anscombian response to this worry is that it’s a mistake to break the act down into component parts, a mistake to think of the intention as something that’s outside of the physical act, either as its cause or as a mental state existing either prior to or alongside it. That’s why she says your hug isn’t given its meaning by the words “you silly little twit” “occur[ring]” to you while you embrace your old acquaintance, they have to be “seriously meant.” And you could mean the hug to be ironic even if you were thinking only affectionate thoughts at the time you administered it, or thinking nothing at all. The correct answer to the question, “why did you hug him?” would still be, to show my contempt.

Making, Meaning, and Meaning by Making

Combine a deflationary theory of photographic agency with a richly intentionalist approach to understanding what photographers mean by making photographs. We are now equipped to make sense of Winogrand’s practice of discovery. The photographer takes a picture of a beggar on the street, not intending that the scene look precisely so. Its looking precisely so is his discovery—it goes to his credit, not the camera’s. At the same time, by making the photograph, he means to tell us something about the beggar and how we should see him. Maybe he also means to tell us something about being a photographer, who means by making, even as what he makes is not just what he means.

A New Limerick, Accompanied by an Essay on the Limerick

The basement has always depressed us.

Class War in the Confederacy: Why Free State of Jones Matters

Free State of Jones reminds us of this core truth of class with respect to labor, whether paid or unpaid—the shared material conditions and shared interests of those who are compelled by force or necessity to work.

On the End(s) of Black Politics

A politics whose point of departure requires harmonizing the interests of the black poor and working class with those of the black professional-managerial class indicates the conceptual and political confusion that underwrites the very idea of a Black Freedom Movement. The prevalence of such confusion is lamentable; that it go unchecked and without criticism is unacceptable. The essays that appear in this section will critique this tendency and offer in its stead a vision of what we think ought to be.

How Racial Disparity Does Not Help Make Sense of Patterns of Police Violence

My point is not in any way to make light of the gravity of the injustice or to diminish outrage about police violence….However, noting a decline—or substantial change in either direction for that matter—in the rate of police killings does underscore the inadequacy of reified, transhistorical abstractions like “racism” or “white supremacy” for making sense of the nature and sources of police abuse of black Americans. Racism and white supremacy don’t really explain how anything happens. They’re at best shorthand characterizations of more complex, or at least discrete, actions taken by people in social contexts; at worst, and, alas, more often in our political moment, they’re invoked as alternatives to explanation