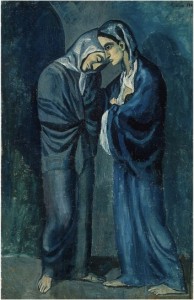

Picasso’s early work—his so-called Blue Period, in the present case—responds to a concern, widespread in the symbolist milieu from which the young Picasso emerged, with authority. By authority, this essay understands one’s ability to believe in and respond to a truth as one finds it represented. In this moment, the tasks of representing truth by art and by religion found themselves in dialogue, or even, as one might say, in a relation of mutual self-definition. Charles Morice’s explanations of Eugène Carrière’s works provide the background against which to understand some of Picasso’s Blue Period works, Morice’s remarks on them, and Apollinaire’s vindication of Picasso. Their exchange raises, furthermore, important problems for those of us who write histories and interpretations of art.