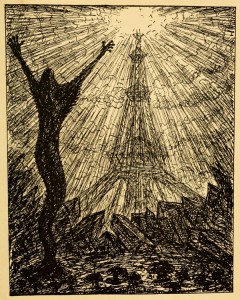

So if it is the case that, as Anscombe says, “I do what happens,” then Kenner’s project is to explore a mode of artistic production that hinges precisely on the point where what happens purposefully occludes what someone is doing. Kenner describes the “principal component” of Eliot’s dramatic method as “his unemphatic use of a structure of incidents in which one is not really expected to believe.” In other words, he builds a counterfeit world for his characters. When we come to categorically not believe what is happening, we begin to think about what they might be doing, “thus throwing attention on to the invisible drama of volition and vocation. The plot provides, almost playfully, external and stageable points of reference for this essentially interior drama.”