Revolution of the Ordinary: Literary Studies After Wittgenstein, Austin, and Cavell

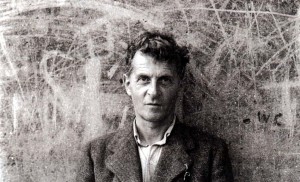

Do we really need Wittgenstein? It depends. I think that literary scholars today really ought to have a workable understanding of Wittgenstein’s vision of language, for it provides a vital and distinctive alternative to other views on the same matters, views that are widely taught. For the same reason, I think literary scholars really ought to understand Wittgenstein’s critique of theory (or, if one prefers, of certain standard notions of what philosophy is). For a literary theorist it ought to be as unthinkable to know nothing about Wittgenstein as it has been to know nothing about Saussure, or Derrida, or Lacan, or Foucault, and so on through the pantheon of more recent theorists. I wrote Revolution of the Ordinary to make this possible.