Issue #37: Contemporary Art and the PMC (Part One)

The first in a pair of issues featuring new scholarship and essays on contemporary art, a professional-managerial enterprise. Edited by Elise Archias.

Maurizio Cattelan’s Managerial Spirit

Maurizio Cattelan couches his artworks as clever, if cynical, escapes from labor. But in truth, he rarely gets out of work. Instead, his art enacts a Euro-Atlantic shift from “productive labor” to “creative management,” a shift that he traces (counterintuitively) to the legacy of Marxian theory in Italy.

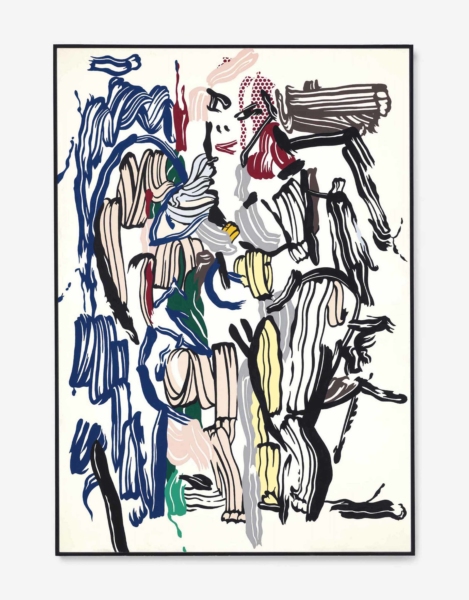

Pop Art and the Fictional Middle Class

Warhol’s trajectory as a working-class Pittsburgh boy turned commercial illustrator turned New York art world icon, we might say, primed him to be particularly attuned to the class dynamics of postwar artistic labor, and particularly able to make them visible. But in fact, I’d like to argue, these dynamics are central to the emergence of pop art in general—in a very real way, they are pop art.

Sculpture as Labor and Sign

None of David Smith’s constructions is ever truly virtualized, truly vaporized, but still, at serendipitous moments, their surfaces spark and crackle with light, and the sculpture’s body is banished, replaced by a scribble, a cipher, a flash. Meanwhile, back in the studio, yet another sculpture is nudged into shape on a much-stained concrete floor.

Infantile “Left-wing” Disorder: An Update

We recognize it when we see it: someone is PMC when they turn to language or rules or theories or style or attitude or affect or critique or (more broadly) culture to measure what they stand for or what they stand against. Compare this to the right for whom cultural coherence, even logical coherence, is the enemy and the uncultured unreason of money and force sovereign. Or compare it to the left for whom what matters as measure is the political organization of workers.

White-Collar Blues: Allan Sekula Casts an Eye Over the Professional-Managerial Class

During the 1970s and early 1980s, Sekula built a theory and practice of photography on his understanding of the aporias inherent to the theory of the PMC, paying particular attention to the figure of the engineer whose task is not confined to the reproduction of capitalist ideology, but plays a central role in the realisation of value.

Introduction: Contemporary Art and the PMC (Parts One and Two)

PMC art rewards a viewer who does not enjoy emotional exchanges, but who does have strong, positive, hopeful feelings every time they figure out how a system works. Contemporary art has helped the PMC feel good about their choices and justified in their limits, in part, because an overriding emphasis on abstraction and system validates the type of solutions that our most lucrative skills tend to generate.

The First Privilege Walk

How Herbert Marcuse’s widow used a Scientology-linked cult’s methodology to gamify Identity Politics and thus helped steer the U.S. Left down the dead-end path of identitarian psychobabble.

The Whole Country is the Reichstag

A crucial characteristic of the current situation is that the antagonism between the pragmatic and the visionary that liberals have often used as a cudgel against left aspirations and programs—the ubiquitous “now is not the time” or “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good”—is passé. The way forward, both to avert the most dangerous possibilities and to begin working seriously to change the terms of political debate, is to push for and propagate a public good framework for government.

Issue #36: The Legal Issue

In this issue we focus on debates—new and old—in the legal and literary sphere, examining topics ranging from birtherism, plea bargaining, forensic architecture and evidence, and robotic free speech. Edited by Lisa Siraganian and Rachel Watson.