Deserts: Cells for certain individuals

Carthusians refer to their cells as deserts. The cell is a remote site at the margins of civilization, distant from the noise of society and mundane temptations. A desert is not only the place where all customs, traditions, and historical stratifications fall apart, but also where any consolidated societal structure can be questioned and examined from an estranged point of observation.

The Recluse

By contrast, what the idea of the rule provides is a relation to the self—to sleeping, washing, eating, excreting and reflecting—that embodies an understanding of the social constituted neither by an assemblage of solitaries nor by the model of the epistolary relations between the writer and the “others” whose “help” he needs to cultivate himself properly. It would be too much to say that in the seven “Deserts” we see the struggle between capital and labor. But it would be exactly right to say that we see emblems not of self-care but of both conflict and of ideology.

Le Corbusier, Matisse, and the Meaning of Conceptual Art

The humanities is devoted to a “bad picture” of intentionality. And the devotion to this picture is embraced above all by anti-intentionalists. Looking closely at the seemingly suspect commitments of two conceptually driven artists—Le Corbusier and Henri Matisse—I show the necessity for distinguishing between inner and outer, idea and execution, and how those terms are mutually imbricated. Failing to address “private” experience, as anti-intentionalists do, generates an inverted form of Cartesianism.

It’s Not About You

The whole point is its refusal of all that: refusal of the parallel-processing, refusal of Foucauldian discipline. It’s a different model of discipline. You go back into your cell and you figure out what you think you’re supposed to do and you can either do it or not do it. Either way, you’re not withdrawing from the office. You’re reconceptualizing the office as a rule, and you’re establishing yourself in relation to the rule. It makes every part of your activity an activity that has some relation to the rule. Especially when you don’t do what you’re supposed to.

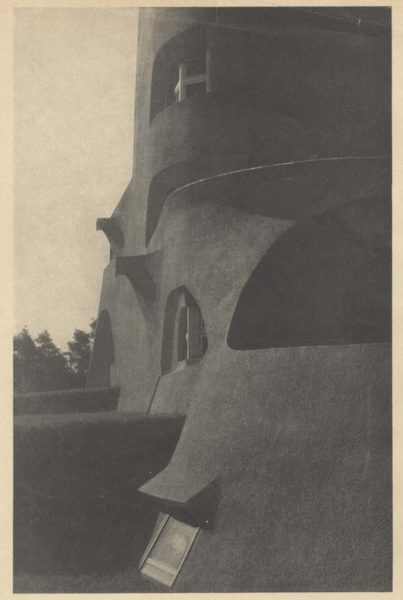

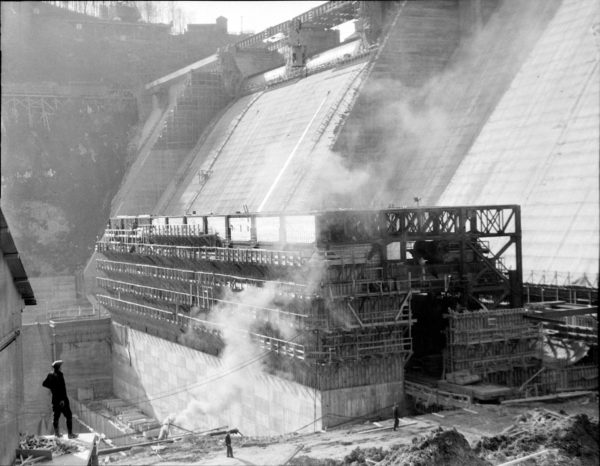

The Light in Architecture: Eric Mendelsohn’s Photographic Expressionism

Erich Mendelsohn’s work as draughtsman, architect, photographer and writer reveals his intense involvement with the development of German Modernism during the 1920s. He was one of the few members of the European Avant-Garde to travel to the United States, and the photographs that he published of his travels provided a radical revision of the American urban landscape and reshaped the perception of the US in Europe. In turn, this shaped the way in which he wanted his own buildings to be photographed, and recognizing the power of photographic effect and the printed page to impact the general public, as well as specialists, he explored the ways in which photography could be used in order to deliver a specific message of Modernity.

Issue #31: Architecture

Inside the issue You May Also Like Issue #24: The Neoliberal Coup

The Ascent of Affect

I offer my analysis in the spirit of a “history of the present,” that is, as an attempt to understand the rise of a non-intentionalist “affect theory” in the light of the genealogy I have charted and to explain why I think the views being forwarded are a mistake.

Change Agent: Gene Sharp’s Neoliberal Nonviolence (Part Two)

Gene Sharp, the Cold War defense intellectual-cum-“Nonviolent Warrior,” is famed for developing a theory of nonviolent action that has undergirded regime change operations around the world. But Sharp also had an impact closer to home: the U.S. protest left. Thanks to a little-known organization from the 1970s called the Movement for a New Society, Sharp’s ideas are ubiquitous on the protest left, bound-up with a rarely named ideology, “revolutionary nonviolence.” Nonviolent direct action is a vital feature of broad-based people’s movements, but historically, “revolutionary nonviolence” has been, at best, ambivalent about, and at worst, antagonistic to questions of class struggle. A closer look is warranted.

The Racial Disparity Politics of Biomedical Research: Disaggregating Categories into New Essentialisms

A recent article in Nature Human Behavior joins a chorus of those calling for public policy and biomedical research to disaggregate reigning forms of racial classification and to construct supposedly more accurate schemes of aggregation that might better account for racial disparities among groups. Despite attempts to remedy past conceptual distortions imposed by socio-cultural, and sometimes even biological, reifications of highly-abstracted and heterogeneous categories, these arguments work to reinscribe additional categories with similarly suspect notions of a shared fate, social essence, and, ultimately, biological content. This political and scientific orientation to racial categorizations and the attendant study of racial disparity threatens to lead us through the backdoor of a newly-reified world of race relations, one which is positioned further away from the necessary conditions to tackle existing social inequalities along with the material conditions that provide for their reproduction.

Jobs for All: A job guarantee puts workers in the driver’s seat

Today, some on the Left are suspicious—or even contemptuous—of the idea of a jobs guarantee, preferring a basic income or similar schemes. But the political pitfalls of basic income are not easy to surmount, meanwhile the advantages of a straightforward jobs program are much greater than critics assume. Ironically, what the business press gets exactly right about a job guarantee is what most skeptics get wrong.