What Materialist Black Political History Actually Looks Like

There is no singular, transhistorical “Black Liberation Struggle” or “Black Freedom Movement,” and there never has been. Black Americans have engaged in many different forms of political expression in many different domains, around many different issues, both those considered racial and not. They have engaged in race-solidaristic formations and in close concert with others, in class-based and multiclass alliances.

What Hegel Would Have Said About Monet

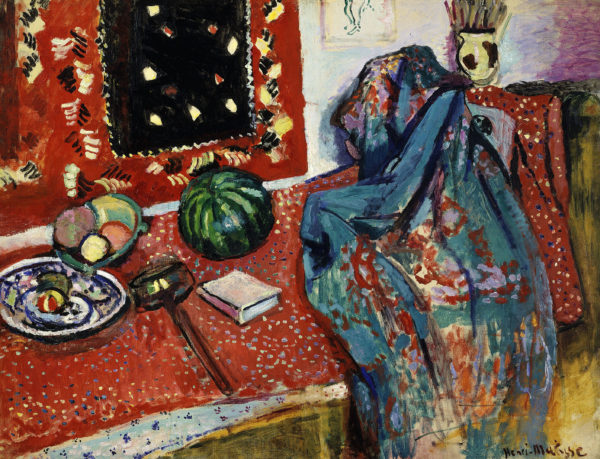

The question I promised to pose in this essay was whether we have an art—a nineteenth- or early-twentieth-century art—to which Hegel’s descriptions of world and consciousness can be seen to apply. I seem to be saying that they only apply, in the art I take seriously, in the negative—they are what French painting is out to annihilate. But for Hegel’s view of things to be worth refuting in this way—with Matisse’s special vehemence—surely in the first place there must have been pictures that exemplified it strongly, beautifully. And yes, there were.

Cézanne Photographic

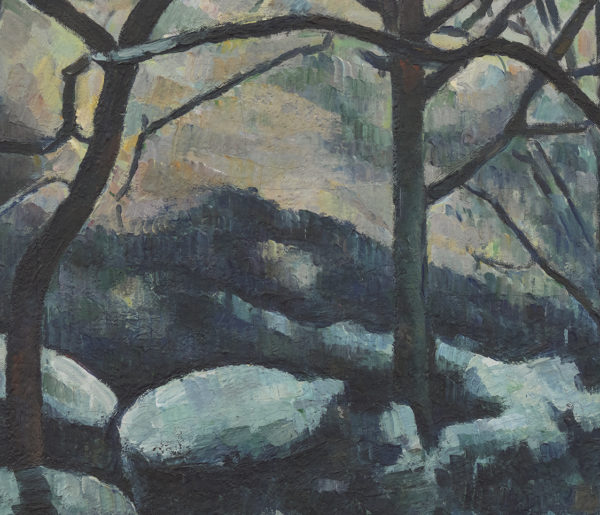

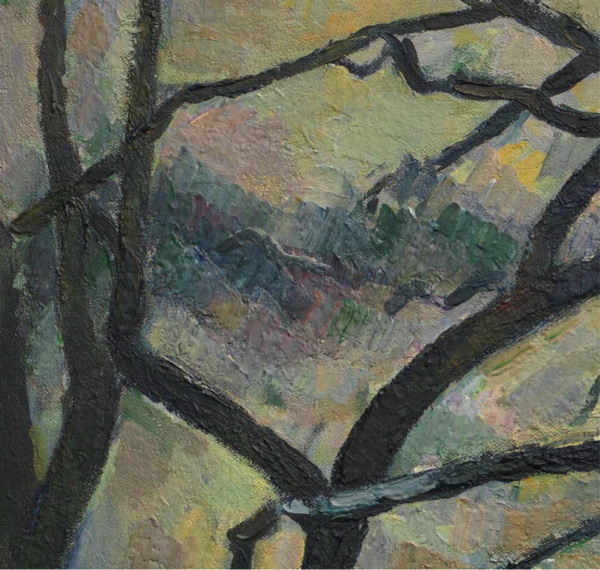

How to represent—or, better, to create—“sensation” in a painting? The challenge was to introduce the experience of external and internal simultaneously. Further complication: the demand would have to be met without losing the active presence of the living artist, that is, without reducing the process to a mechanism. A problem for photography: even when it exhibited blur, it suffered the slur of appearing mechanistic. A satisfying image of nature would need to incorporate, on the one hand, nature’s essential animation, and, on the other hand, the animation associated with the living, sensing being of the artist—the artist as both sensing nature and recording this sensation.

The Medical Portrait: Resisting the Shadow Archive

In spite of the historical and ethical difficulties these photographs pose, I would argue that the hesitations are worth overcoming, as the images have a great deal to teach us about the power immanent in the very act of posing for a picture, even when the imagined audience remains unseen. Through the photographs made at the Holloway Sanatorium, a modicum of agency may have been granted to those who were generally presumed to be without it. And thus, even if only for the span of time it took to stage and take the photograph, a highly vulnerable person could resist being reduced to the category of specimen, and could become, instead, a subject.

Secrets of a Mystery Man: Wilhelm Schadow and the Art of Portraiture in Germany, circa 1830

In an age acutely aware that revolutionary upheaval had broken the continuous thread of history, the question of how a modern identity would navigate between the desire for historical continuity and the need for contemporaneity was as crucial as it was painful. After all, even Charles Baudelaire desired to distil the eternal from the transitory, and defined modernity through this gesture. Thus, Schadow’s pictures remind us that the geo-political desire for a German identity intersected with the specific desire undergirding the more general quest for a modern identity.

Gustave Caillebotte’s Interiors: Working Between Leisure and Labor

To extrapolate directly from Caillebotte’s class a certain mindset that forms the hermeneutic ground for reading the economy of his paintings runs the risk of striking a false equivalence between Caillebotte’s structural class position and his imaginary relation to that position as it manifested in his activity. Rather than dispensing with alienation as an analytical category founded on a Marxist critique of modernity while retaining the restrictive class-determinism of Marxian thought, it will be more productive to retain the former and dispense with the latter.

Issue #26: The Nineteenth Century (Part One)

Inside the issue You May Also Like Issue #40: New Views on Modern Architecture at Mid-Century

Issue #25: Authorship/Anti-Authorship: Legal and Aesthetic

Inside the issue You May Also Like Issue #31: Architecture

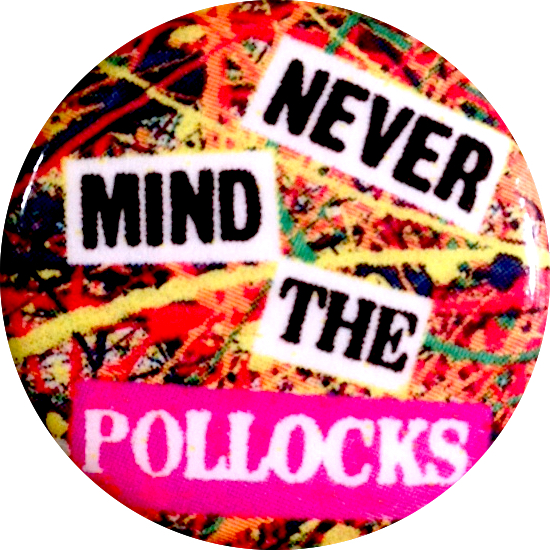

Never Mind the Pollocks

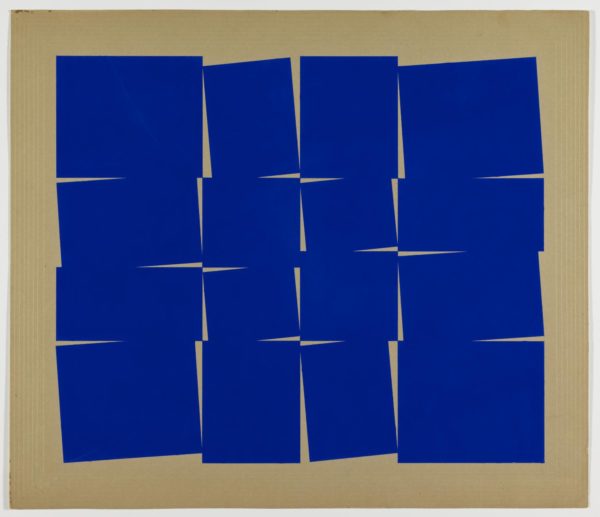

It might seem idiosyncratic to scrutinize such tiny details in such a large painting: Cathedral’s surface area is eighteen square feet, each dot I have discussed smaller than a dime. Yet my purpose in calling attention to Pollock’s small-scale painterly decisions, the evidence of which he left plainly in sight, is to demonstrate his fastidious concern with the integrity of his surfaces. From the perspective of their studied particularity, limiting the use of “all-over” to describe stylistically the putative uniformity of Pollock’s canvases forecloses the possibility that “all-over” might just as well designate the intentional character of every mark. In Pollock’s automatism, everything matters, at least potentially.

Wrongful Convictions: The Nineteenth-Century Droit d’Auteur and Anti-Authorial Criticism

By analyzing the Gros case in relation to nineteenth-century French law concerning the droit d’auteur, this essay offers evidence against one of the central historiographical postulates advanced in anti-authorial criticism: that the displacement of an interest in an author’s meaning onto a reader’s productive activities represents or would have represented a subversive blow to the modern proprietary regime of authorship. More specifically, I will dispute the plausibility of certain supposedly critical alternatives to the author, be they Roland Barthes’s modern scriptor or his emboldened readers, by demonstrating that the criticality of these positions depends upon a mistaken view of what historical authorship entailed and, more tendentiously, by suggesting that these same alternative “authors” had already been furnished with rights of their own.