Hélio Oiticica, Tropical Hyperion

Helio Oiticica’s career tells the story of the democratic leap of art off the wall and into life, out of contemplation and into action and experience, from autonomy to involvement, from elite contemplation to democratic participation, from aesthetics to politics. This narrative, which carries the authority of being the story Oiticica himself wanted to tell at one point in his life, is not false. And yet the truth lies elsewhere: closer to the works themselves and, only apparently paradoxically, in the great political crosscurrents that tore through the Brazilian 1960s.

Reading Art and Objecthood While Thinking about Containers

Fluxus containers, in summary, initiate the beholder (a holding, handling beholder, maybe a tool-being holder in the Heideggerian sense) to explore and take interest in the world. The boxes sensitize the user to a world where the public is overwhelmed and numbed by the excess goods proliferating, literally ad nauseum, in the world and landing in the seconds bins along Canal Street, where Maciunas made use of them as artworks. The kits express a collective obligation (or opportunity) to repurpose the excess manufactured articles of late capitalism.

Farago’s Global Art History

Again: is this Farago’s politics, or is this something deep in the DNA of global art history? Insofar as globalization concerns itself with “subject positions,” it seems clear that struggles for state power and deep changes to the relations of production and the exploitation of labor are not just beyond its grasp but irrelevant to it.

The Luminous Elsewhere

Eighteenth-century intentionality was less a directional striving or will, than disclosive, something that made us aware of our being in the world. What the senses do, in this sense, is to make the world available, rather than keep it at a skeptical remove. Perception…is a “skilled attunement.” It is Lajer-Burcharth’s singular achievement to give us a very different eighteenth century, a “luminous elsewhere” that’s also right here with us. And radically ordinary.

Theaster Gates’ Social Formations

As artist and urbanist, Theaster Gates is his own patron, his own institution, his own LLC. He is start-up and content creator combined. Though artists have long engaged in corporate parodies, Gates goes beyond the twee anarcho-entrepreneurship of the Bernadette Corporation or the politicized media takeovers of the Yes Men. He creates new art spaces as anchor institutions in blighted blocks. His works propel white creative types to penetrate black areas of the city formerly unknown to them. His renown encourages art tourists to travel beyond the usual downtown museum circuit. But Gates does not draw attention with mural paintings or large public sculptures. Gates’ artwork is, simply, real estate. And there is real money at stake.

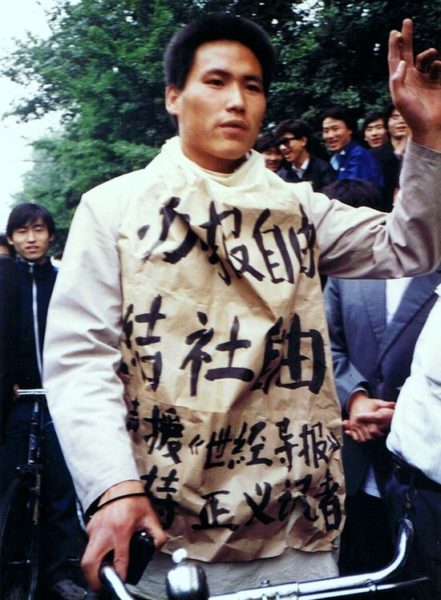

From a Rooseveltian Dream to the Nightmare of Parliamentary Coup

In Brazil, the first decade of the twenty-first century was characterized by a successful but moderate reformist program spearheaded by its president from 2003-2010, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, universally known as Lula. His successor hoped to accelerate the project on the wings of a Rooseveltian dream: to create “in just the space of a few years” a country in which the majority could lead “recognizably similar and remarkably decent material lives.” What happened?

Class Struggle in Brazil: The Neoliberal Coup, an Attack on Workers and the Poor

The neoliberal program includes: a) the drastic reduction of the federal budget, with a direct impact on social welfare, education, public health, and research spending, a.k.a. “the death budget”; b) labor legislation reform, removing or weakening many of the longstanding protections enjoyed by Brazilian workers and, under the guise of creating “flexible” labor relations, undermining the country’s trade-union movement; and c) social security reform, imposing stricter and longer work requirements, which, given the current and past employment structure would make full retirement unattainable for large sectors of Brazil’s working class.

Defamiliarization and the Unprompted (Not Innocent) Eye

The aim is to revive the concept of defamiliarization by showing that it has nothing to do with the Innocent Eye and to propose a new interpretation of it in terms of distributed attention. This reinterpreted concept of defamiliarization can be useful for contemporary post-formalist accounts of the history of vision, imagination, and visual attention.

Populism or Capitalist De-modernization at the Semi-periphery: The Case of Poland

There is, finally, one more reason why only a unified front of Old and New Left may be successful in countering both neoliberalism and populism within parliamentary politics. An important—I’d say even the largest—part of progressive political mobilization is nowadays done by women. At least that is the situation in Poland. It is obvious that women would not give up women’s causes and fight just for redistribution under the banners of the Old Left. We do not need, however, to treat this as a limitation or predicament. As a matter of fact, the women’s struggle is undoubtedly the biggest and the most important single positive factor in contemporary Polish politics, a fact that was very well epitomized in autumn 2016 by the so called Black March and women’s strike in opposition to the possibility of further restrictions on a Polish abortion law that is already one of the most restrictive in the EU.

Issue #24: The Neoliberal Coup

Inside the issue You May Also Like Issue #20: Political and Aesthetic Post-Mortem