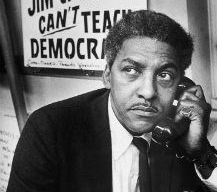

Bayard Rustin: The Panthers Couldn’t Save Us Then Either

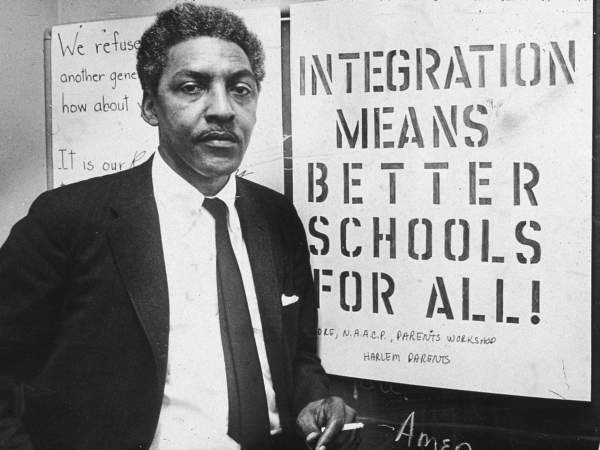

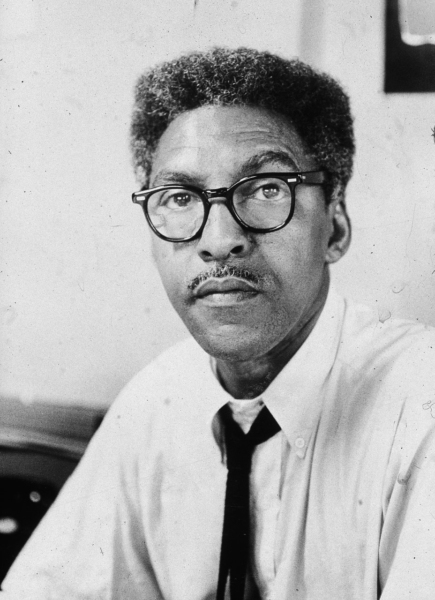

Rustin saw politics through a concrete, strategic lens, which provided a perspective that has become increasingly remote from both academic and activist experience. Indeed, as demonstrated in the essays selected here, he explicitly rejected the moralistic discourse that he saw undergirding much of Black Power and New Left politics, as well as the tendency to reduce the sources of inequality to psychologistic factors like prejudice, discrimination, or a generic racism.

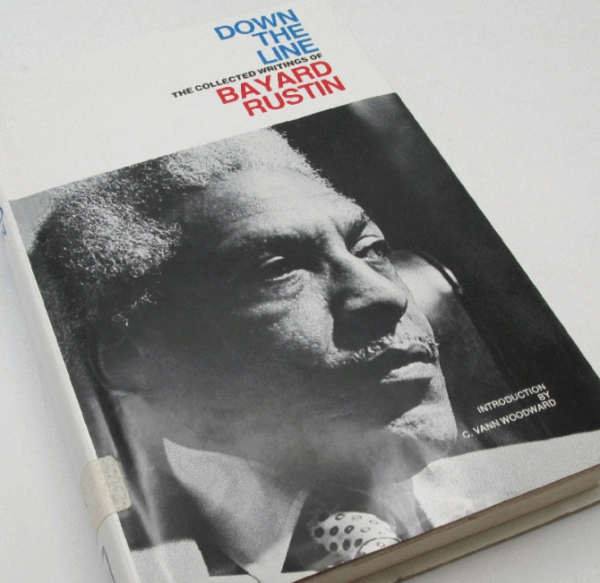

Introduction to Rustin’s Down the Line (1971)

Black capitalism is endorsed not only by Roy Innis of CORE but by President Nixon and various corporate interests. It does not cost much, and it leaves ghettos intact. The vast majority of black people, of course, are not capitalists and never will be, and they stand to lose from “buying black.” For black workers to define their problem primarily in terms of race is to ally themselves with white capitalists against white workers. It is the old strategy of Booker Washington in new guise. As Marcus Garvey put it, “The only convenient friend the Negro worker or laborer has in America at the present time is the white capitalist.”

Education?

The only way to really help the poor is to establish opportunities, as part of the total economic order, which in some way reflect the manner in which the poor immigrants gained a foothold in American society. It becomes tiresome to hear people who were very poor when they got here talk about how they lifted themselves by their bootstraps….Now they think they did, but they didn’t….I am for all kinds of educational programs. But education as we know it is not relevant to the fundamental problem of poverty. We must concentrate on providing people with opportunities to relate productively to the life of the society.

What About Black Capitalism?

But the economic impact of black capitalism has been—and can only be—marginal at best, and if we are not careful, this approach may actually compound the injustices from which Negroes suffer. We must not forget that businesses are “in business” not to attack social injustice but to make a profit, and that the ghetto represents a poor market to invest in because of its poverty and deprivation.

Socialism or Moralism?

I maintain that there are two elements in our society which can block Nixon’s strategy and they are the labor movement and the minorities, particularly the blacks. I, therefore, say to the young people in the Socialist League: You ought to recognize that economic progress is the basis for maintaining our coalition—that we are going to win because we emphasize, above all others, the economic issues in this society. Because there is no possibility for black people making progress if we emphasize only race. You can psychoanalyze every white person in the United States until he comes out pristine pure tomorrow morning, filled with love for black people—and that will not provide jobs for blacks or build housing. That is a political task which we must face.

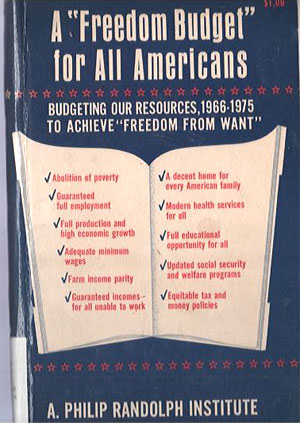

Firebombs or a Freedom Budget?

This society never has and never will do anything special for the Negro. That is the reason we call it the freedom budget for all Americans. It is not that I do not know that Negroes are most brutalized by poverty for they are! But I also know that 67 percent of the poor are white and unless we are going to draw up programs which have to do with the elimination of poverty and not concerned with Negro poverty we will not get anywhere in the society.

Issue #41: Socialism or Moralism

Inside the issue

Four Sonnets

And suddenly, the words are gone again

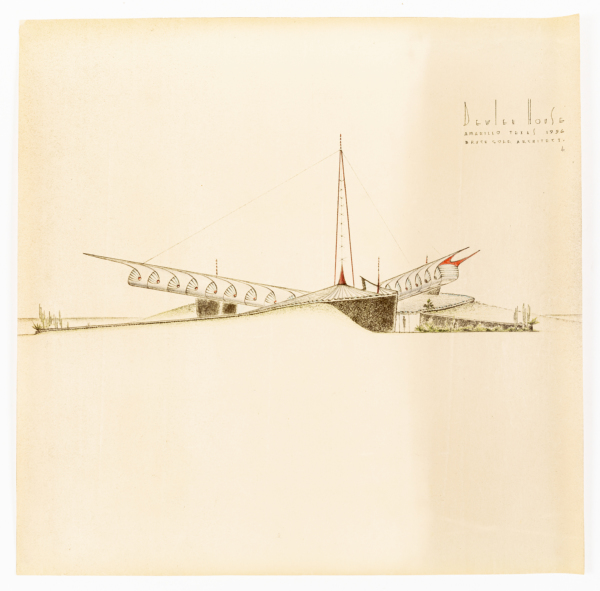

Issue #40: New Views on Modern Architecture at Mid-Century

This issue is devoted to new approaches to lesser-known architecture and design at mid-century. Examining a range of practices at mid-century, all of them within a highly politicized landscape, these essays explore Otto Neurath’s studies in scientific management, Bruno Mathsson’s Solar Architecture, reconceptions of building art for the uninhabited wilderness, the incredible story of the intersection of the work of Alden B. Dow and Dow Chemical, and a study of the contrasting approaches to architectural photography in the work of Julius Shulman and Ezra Stoller. Finally, Adolph Reed cuts through the ideological jargon of Afropessimism.

Afropessimism, or Black Studies as a Class Project

The close parallel between fin-de-siècle racist ideologues’ assertions of the primordial and immutable nature of white supremacy and contemporary race reductionists’ can provide perspective helpful for ascertaining what lies behind the impulse to insist, in the face of such overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that nothing has changed for black Americans and, yet more strikingly, Hartman’s dismissal of Emancipation as a “nonevent.”