Issue #9: The Labor Issue

Nonsite’s 9th issue focuses on working conditions in higher education. Edited by Victoria H.F. Scott.

Issue #9: The Labor Issue

Nonsite’s 9th issue focuses on working conditions in higher education. Edited by Victoria H.F. Scott.

Going Back to Class: Why We Need to Make University Free, and How We Can Do It

Far from spelling the end of neoliberalism, the economic crisis now marching into its fifth year has intensified it, proof that this increasingly dystopian order will not collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. Its fate depends, above all, on the balance of class forces in this country, and tilting that in our favor requires diligent organization and capacity building.

Academic Labor, the Aesthetics of Management, and the Promise of Autonomous Work

An insistence on autonomy, here, is not about continuing to valorize the self as a site of all meaning and value. The opposite is true. Autonomization is a fundamentally social process. It is a matter of vigorously and loudly arguing for the necessary existence of modes of inquiry, styles of life, and ways of organizing creative and scholarly activity that reveal the limitations of the neoliberal market as an arbiter of what is valuable to know and do.

Bartleby’s Occupation: “Passive Resistance” Then and Now

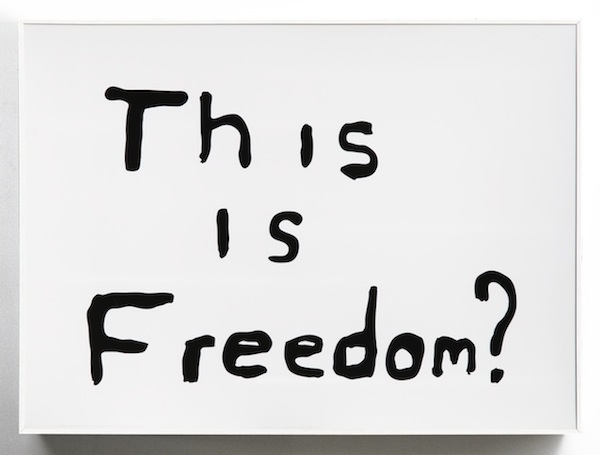

For, when the neoliberal state has been absorbed by the market, how is it possible to resist it? Or, to put the question in a simpler form, how does one “resist” the market (essentially, the question posed by “Bartleby”)? Neoliberalism, of course, has no interest in answering this question; its account of political resistance is not resistance to the market, but resistance in the market. In other words, resistance itself essentially becomes privatized, as political principles find their primary expression in market preferences.

Todd Cronan and Simon Critchley, “The Ontology of Photographic Seeing”

Video of Todd Cronan and Simon Critchley in conversation at The Photographic Universe II.

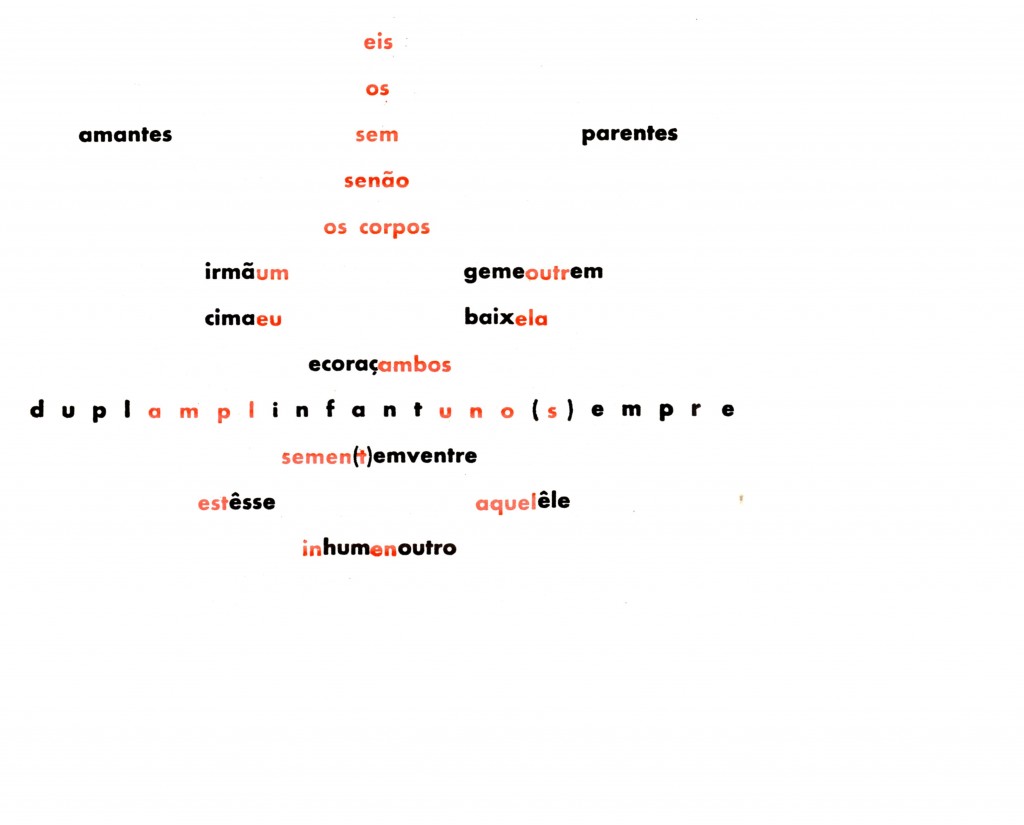

The Anti-Dictionary: Ferreira Gullar’s Non-Object Poems

Gullar gave primacy to the word as the locus of meaning of the non-object poem, and the visual, whether the materiality of language or the sculptural turn of his Neoconcrete art, opened up additional meanings contained in the word. According to Gullar the non-object as anti-dictionary cannot be reduced to one meaning or limited to only an arbitrary sign. Like the visual non-object, the verbal non-object avoids sameness or commonness and rejects the ability of language to only designate. And yet paradoxically, are not all words readymades themselves?

Some Passages from Virgil’s Eclogues

That was the day Corydon became Corydon.

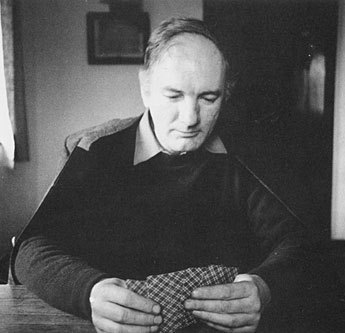

Bernhard’s Way

Bernhard can link a Bourdieu-style sociological critique of art to an anti-theatrical critique of art because both the sophisticated collector and the actor depend on the pretense that they are not doing what in fact they are doing: asking you to recognize them. People make judgments of taste in order to be recognized by others. Painters paint paintings, actors deliver lines, poets write poems in order to be recognized by others. The objects they create come into the world deformed by their attention-grabbing fineness of line, color, and phrase.

Ecological Art: What Do We Do Now?

Araeen’s “ecoaesthetics” insists that artists can and should make a difference in a world beset by environmental emergencies. He shows one way to move in this direction, by collectively implementing artistic ideas. Thinking of his polemic and of the many and various ecoart projects realized in recent years, we could be forgiven for wondering how much of a difference in this direction is “enough.”