Art and Political Consequence: Brecht and the Problem of Affect

As critics have ceaselessly argued, the core problem with Brecht’s art and theory is his didacticism. Brecht undoubtedly saw art in moral and political terms. Moreover, he thought that morality was a consequence of his works. He described all works of art as “necessarily…bound to release emotional effects.” The only difference between his moralism and the moralism of “bourgeois” art was that he believed his effects could fail. Even though all works produce emotional effects, the job of the (non-bourgeois) artist was to defeat the free play of affect. Brecht’s art continually thematizes open-ended affect as the thing to be overcome, or to show how it had not been overcome by his characters, making that failure a problem to be resolved outside the theater.

Kurt Weill, Caetano Veloso, White Stripes

We are concerned with the problem of securing meaning against the ideological horizon of a fully market-saturated society. Meanings circulate or fail to circulate, compel or fail to compel. Success in the former, which is easily quantifiable, does not guarantee success in the latter, which is not.

The Time of Capital: Brecht’s Threepenny Novel

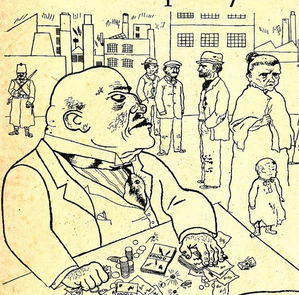

The Threepenny Novel is not just a book about capital. It is also a book about Kapital. Brecht’s commentators have amply documented The Threepenny Novel’s numerous borrowings from Marx’s opus, such as the passage describing the death of Mary Ann Walkley, which Brecht quotes virtually verbatim from Marx. But, beyond the content and imagery, correspondences between the two works can also be found at a deeper structural level. Indeed, far more intriguing for our inquiry are certain parallels in the construction that raise questions about the aesthetic strategies Brecht borrowed from Marx to represent capital.

Writing Against Time

I don’t notice the sky on my way to work. I couldn’t say what colors my neighbors’ flowers are. In fact, I’m not even sure that they have flowers…But if, as Scarry argues, the flowers in books are in constant danger of dying for want of the solidity of real flowers, then what is killing the real flowers? And what is the medicine? The analysts of literary effects from Edmund Burke through Viktor Shklovsky, from Scarry to the latest cognitive critics, have been distracted by formal features, structures, and techniques. The sickness of literary flowers may be a problem for literary technique. The sickness of living flowers is a problem for philosophy. And this philosophy, as I will argue, has been the constant practice of a literature that doesn’t want to imitate life, but to transform it.

Anthony Caro’s Park Avenue Series

Eventually the Park Avenue series will be recognized as one of the major triumphs of Caro’s long and distinguished career, and in particular as a knockdown demonstration of the continued viability of high modernist abstraction in the face of the widespread assumption that no such thing is any longer even conceivable.

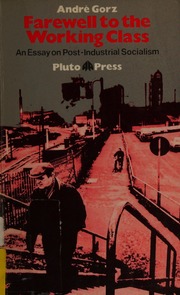

When Exclusion Replaces Exploitation: The Condition of the Surplus-Population under Neoliberalism

The central problem with which we are confronted today, in other words, may be less the conflict between labor and capital, and more, as Margaret Thatcher put it, the antagonism between a privileged “underclass” with its “dependency culture” and an “active” proletariat whose taxes pay for a system of “entitlements” and “handouts.”

Three Poems

…the black lead of his carpenter’s pencil has been pressed into the paper with tremendous force, far exceeding the demands of the form or the requirements of the shading in that precinct of the image…

Issue #10: Affect, Effect, Bertolt Brecht

In nonsite’s tenth issue, we revisit the work of Bertolt Brecht and assess its relevance for today.

Issue Print Test

In metadata, set “print-issue” to the issue you want to print and it will put the whole thing into one giant post. The format needs to be finessed to make it print out like a full issue, but it is getting there! To do: add the issue description as an option… Why isn’t the issue […]

Neoliberal Art History

Putting aside the one-dimensional account of artworks as “reifications”—“mediums lead to objects, and thus reification”—it would take only a moment’s reflection to see that the distribution of wealth in the “era of art,” at precisely the moment Joselit’s “reframing, capturing, reiterating, and documenting” paradigm first emerged (a set of procedures exemplified for him by the work of Sherrie Levine) was also the moment at which the US economy began its most aggressive turn away from equality.