So we have two modes of politics. One that depends on your subject position and one that doesn’t. And we have two kinds of art: one that depends on your subject position and one that doesn’t. And they align themselves, one with the other, according to what they assume about representation and about truth. Which kind of art is Miró’s? Or is it another kind altogether? And what kind of politics does it embody?

BY Todd Cronan

A review of Lisa Siraganian, Modernism’s Other Work: The Art Object’s Political Life. Oxford University Press, 2012.

…if we wanted the unrich to stop being such a (vastly) underrepresented minority in our universities, we’d have to throw most of our current students out. From this standpoint, the most effective version of an occupy movement on campuses like Michigan’s would be one in which the students stopped occupying it and made way for not the 99% but the 75% who have been systematically denied admission.

BY Todd Cronan

Video from talk given at Publishing and the PhD, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, October 18.

It is a facsimile. It is facial angle:

European woman. It is stomach

simple, similar to a box. It is on

either side of inside. It is grapple.

It is extracted from lignite and peat.

It is worn by women. It is whether

with gloves, a moveable roof.

It is concerned with whalebone.

It is a writing material made of strips

of parachute. It is myth, cat,

machine. It is a cloth conclusion, of

silt formerly. It is this, thin, azure.

It is the plates of the skull for

signaling. It is a scout concerned.

It is the envelope embloomed.

It is cavity, clock, cloth. It is a paper

book. It is plasticized. It is of sea

or not. It is to a petal of another

person. It is as wine of a mixture.

It is when the sum moved.

It is knot, see illus. It is alone

and onerous. It is veins as emissary.

It is a sickle compressed. It is a pair

of ghosted cranes, of silk formerly.

It is dignified, sedate, staid, etc.

It is where repair works gore

(of a skirt). It is to the library

foundered. It is a clumsy patch.

It is when the issue is one not of fact

but of law. It is banish.

BY nonsite

New accounts of Picasso, Léger, Beckmann, Pollock, Bearden and we ask: What are the stakes of formalism today?

BY nonsite

New accounts of Picasso, Léger, Beckmann, Pollock, Bearden and we ask: What are the stakes of formalism today?

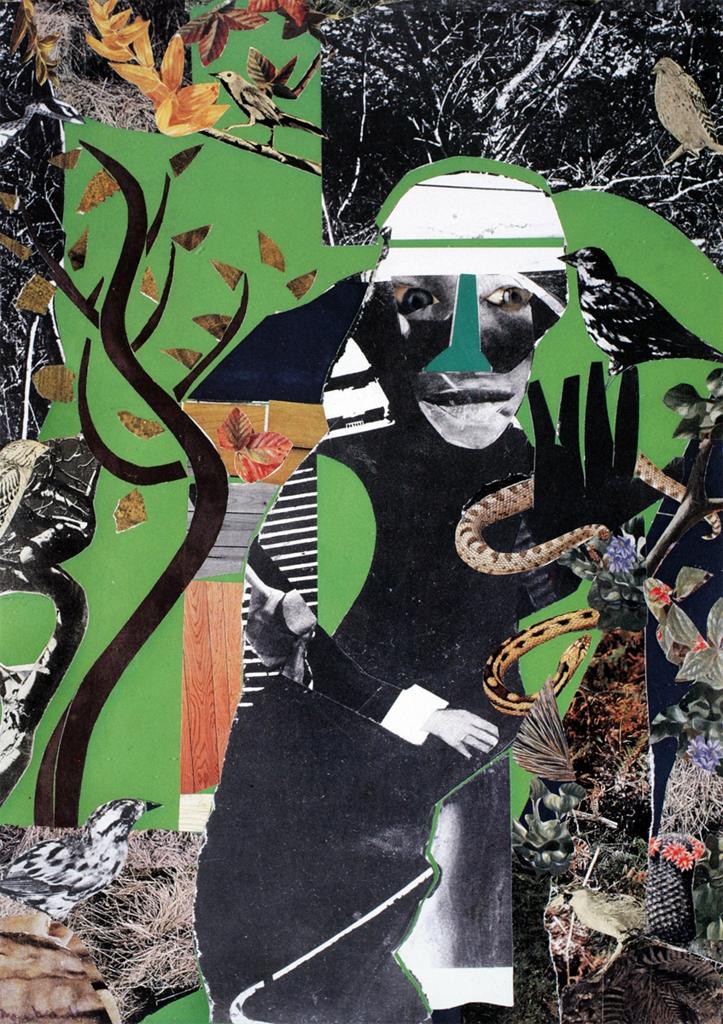

Bearden wanted his collages to conjure. Of course, all representational images conjure in the sense that they gather together colors and shapes to form an image of the world and in so doing call to the minds of their viewers various ideas, emotions, associations, and memories. But in making the conjur woman so prevalent in his imagery and in adopting the medium of collage, which by its very nature extracts material from the world and then transmutes it, turning so many scraps of paper into a novel physical form, Bearden suggested that he had in mind for his art an instrumentality beyond the norm, a capacity, akin to that of the conjur woman, that exceeded human limits and approximated new ways of seeing and being.

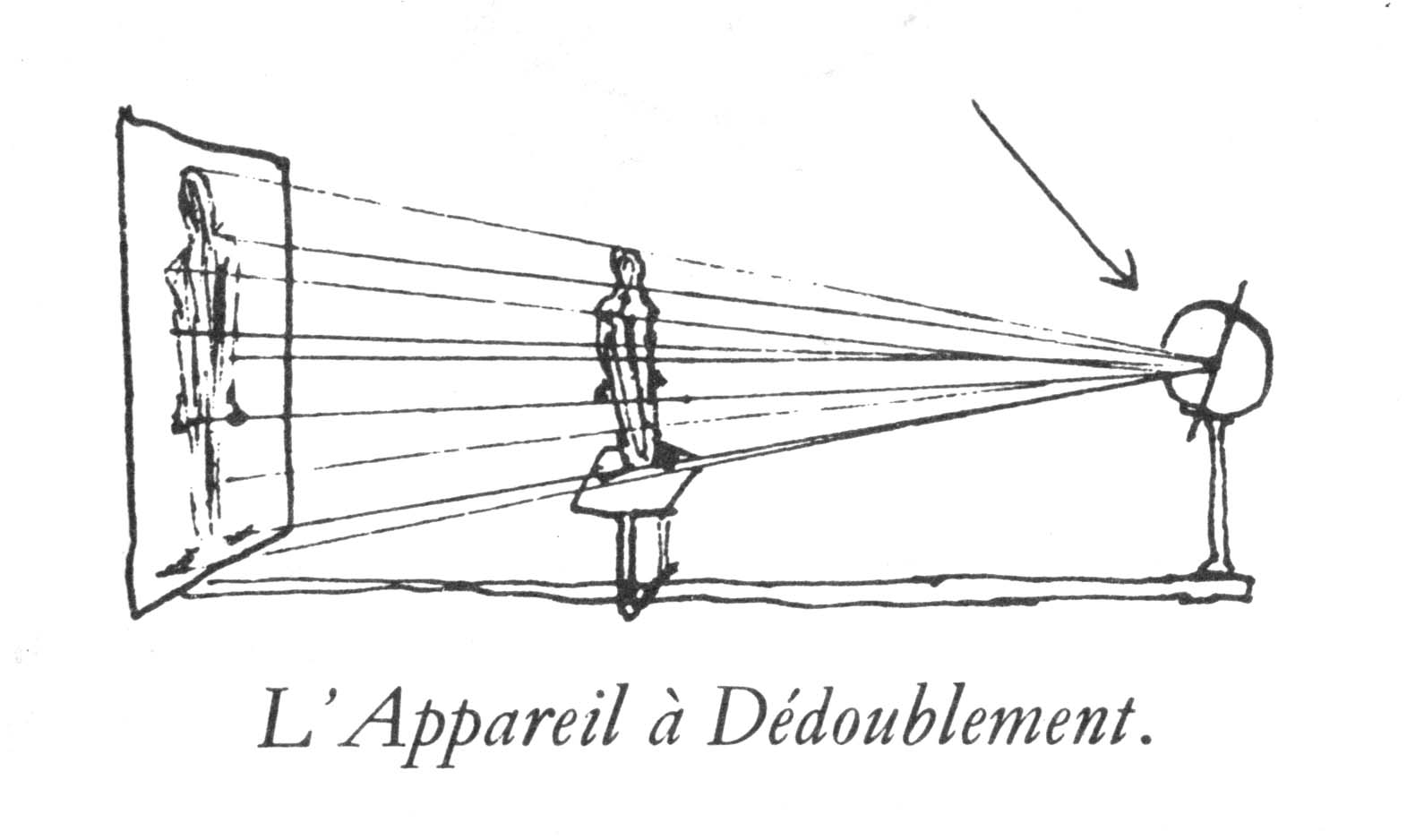

In excavating the optische Schichten in which artworks—that is, drawings, paintings, sculptures, and so on—are constituted…post-formalist art history calls for histories of the aesthetic orders and structures (as it were the “art”) of human vision, of imaging and envisioning, that is, of its active imaginative force whether or not any actual historical artwork was (or is) in vision or in view. The optical appearance of visual artworks—the supposed object of Wöfflinian formalism—is becoming less important analytically than the configuring force of imaging, regardless of what is imaged.

BY Lisa Florman

The combination of flatness, enframing, and the implied interchangeability of consumer goods that we see in Warhol’s Soup Cans is both characteristic and telling. In front of such works, I can only think of what the philosopher Martin Heidegger referred to as the “standing reserve.” Insofar as our present sense of reality is shaped by the technological age in which we live, we increasingly treat all entities, Heidegger claimed, as intrinsically meaningless “resources,” a “reserve” standing by merely to be optimized and ordered for maximally flexible use.