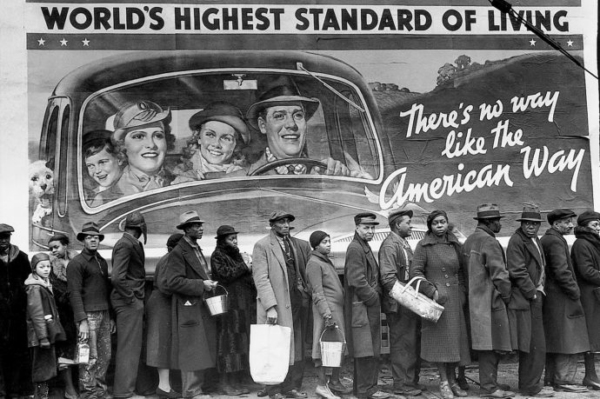

Most political discussions of New Orleans since the 2005 Hurricane Katrina disaster have relied heavily on notions of the city’s exceptionalism. Right-wing pundits pointed to the city’s reputation for corruption and its citizens’ alleged complacency and poor planning decisions (e.g., “Why would they build below sea-level?”) as central causes for the disaster, rather than the austerity or hubris of the Bush White House. This image of New Orleans as a political backwater or banana republic was used by some Congressional Republicans to discourage further federal investment in rebuilding the city. Liberal activists and city boosters, in turn, reached for notions of cultural particularity to stake their claims for the city’s reconstruction, arguing that the Crescent City’s unique colonial heritage, architecture, and sundry contributions to American music and foodways were all precious national resources. The trope of native cultural authenticity ultimately served to unite right of return advocates who insisted that New Orleans would not be the same without its black working class neighborhoods, and the various commercial interests that comprise the tourism-entertainment complex, around a recovery agenda that has still reproduced inequality and segregation. This essay explores and rejects another prevalent notion of exceptionalism, the underclass myth that has been central to the defeat of welfare statism in the United States, and especially influential in shaping the market-oriented reconstruction of New Orleans.