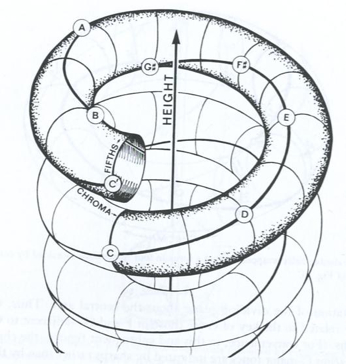

In excavating the optische Schichten in which artworks—that is, drawings, paintings, sculptures, and so on—are constituted…post-formalist art history calls for histories of the aesthetic orders and structures (as it were the “art”) of human vision, of imaging and envisioning, that is, of its active imaginative force whether or not any actual historical artwork was (or is) in vision or in view. The optical appearance of visual artworks—the supposed object of Wöfflinian formalism—is becoming less important analytically than the configuring force of imaging, regardless of what is imaged.