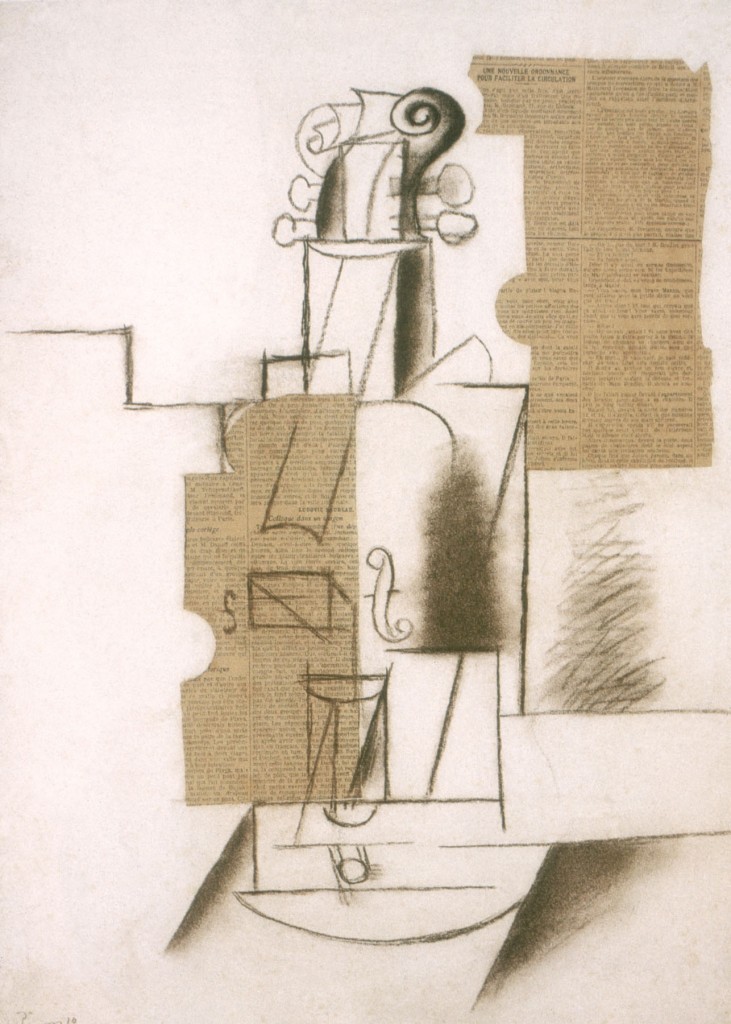

Modernism, Theatricality, and Objecthood

The imperative to establish an artistic medium means that the artist herself must somehow assume the authority to determine and declare how her work is to count for us, determine as just what medium of art it is to confront its specific possibilities of success and failure. In art, as well as in ordinary speech and gesture, possibilities of meaning and expression exist only insofar as there are answers to the criterial questions of what sort of thing is the subject of expression here, what speech, what action, what medium of expression.