Produced and Abandoned: Action and Intention in Derrida

The problem, as we’ve already begun to see, is that once you’re committed to the idea that meaning is something you try to control and/or that it’s something you impose, you’re committed also to an account of the text in which the intention must be (what Derrida rightly denies it can be) outside of it. Indeed, this is exactly what the reduction of the text to the mark requires since the act of writing is here conceived as the writer’s effort to impose a meaning on the mark she has made and since the act of reading involves the impositions of other meanings, which need not be the same as the writer’s. The reason the mark is abandoned is because that imposition necessarily fails, leaving a remainder that remains necessarily “open.”

Corporate Communiqué: The Derrida-Holmes Merger

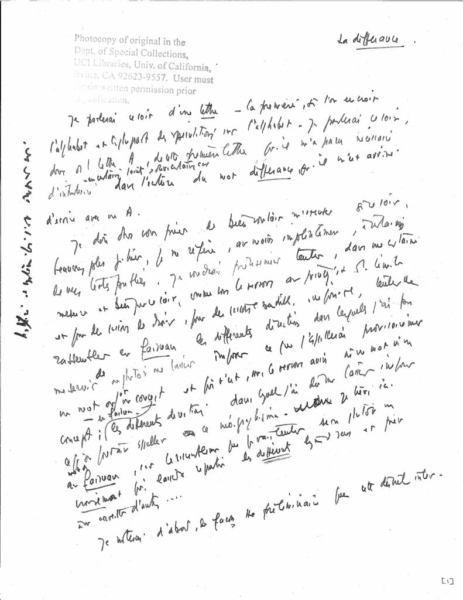

I want to argue that Derrida’s provocative invocation of a corporation reveals certain premises that deconstruction shares with the corporate legal form, and that both mistakenly assume—in their theorizing—that intentions are causes. More specifically, Derrida’s picture of communication was already, for late-nineteenth-century legal theorists, their problem of corporate intention. How should people understand what is happening when they negotiate with vast collective social agents whose intentions seem unreliable or unknowable?

“Signature Event Context” and The Possibility of History

How is history, as a discipline and a practice of writing, possible? “What happens in this case, what is transmitted or communicated,” Derrida argues, “are not phenomena of meaning or signification” (SEC, 309). If we are trying to communicate with or, more importantly, to listen to this distant past, there are traces or fragments of the past that resist immediate significance or comprehensible meaning but are still telling us something of historical value. It is from these traces that we write history.

Performative Contexts

Is all this to say that we should give up on context because we can have no purchase on it? I think it is rather a way of pointing to the constitutively incomplete nature of what is still the necessary task of making sense of texts in context. For every context that fails to determine its text completely because it, itself, is structurally indeterminate, new contexts come to impose their force and their relevance. The flip side of Derrida’s claim that every text ruptures with its context is his assertion that texts are citable and reinscribable in other contexts, for belonging to the structure of every mark is both “the possibility of disengagement and citational graft.”

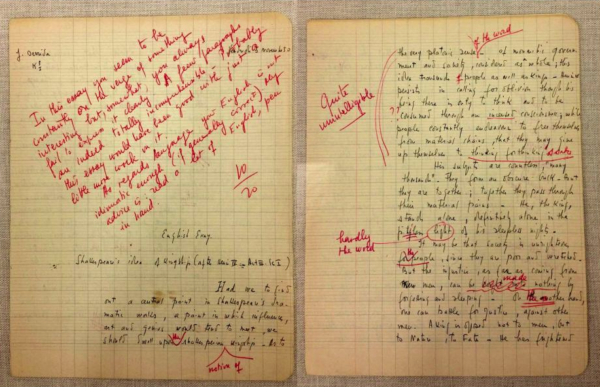

Write, Rinse, Repeat: Text and Context in Derrida’s SEC and in Literary Studies

None of what the text says and is about can be determined beginning from such considerations, however; texts are not functions of cultural, social, or historical “structures” or “logics.” Such suppositions erase the text itself, by subordinating it to new and again unexplained systems or structures, implicitly resurrecting the ideal. Appeals to structures or logics necessarily trade on otherwise unexplained ideal last instances, ones hailing now not from language but from society, history, the economy, and so on. Their invocation thus renders the text in question effectively equivalent to the common understanding of “now is night,” an inscription somehow without a writer, receiver or context—subordinating it to a new ideal instance and thereby depriving it of its status as an authored text.

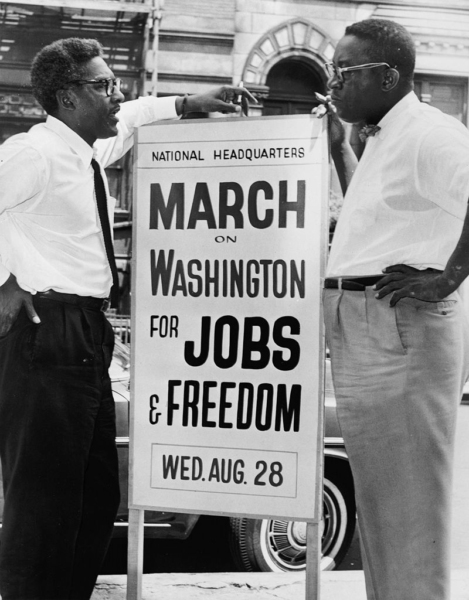

The Obamas’ “Rustin”: Fun Tricks You Can Do on the Past

The project of “reclamation and celebration” proceeds from a common impulse to rediscover/invent black Greats who by force of their own will make “change” or “contributions.” In Ava Duvernay’s Selma Martin Luther King, Jr. shows up and exudes a beatific glow that makes things happen. These films and filmmakers have no clue how movements are reproduced as mass projects, from the bottom up and top down, in a trajectory plotted by continuously improvised response to and anticipation of layers of internal and external pressures. But that’s not their point. Rustin isn’t interested in illuminating the intricacies of the civil rights movement; it wants us to recognize its subject’s place in a pantheon of black and American Greats.

Paula Peatross: Purposefulness with no Purpose

This is not a distinction between nonrepresentational and representational art, but it is one between narrative and nearly everything else. And Peatross’s reliefs are unambiguously nonrepresentational. In addition to not being narratives (stories) of any sort, they are made without reference to anything else outside themselves, such as a landscape, the sole exception to that general rule being that they do preserve the limits and inflexions of her body. That aside, as the artist herself puts it, “Each one is itself.”

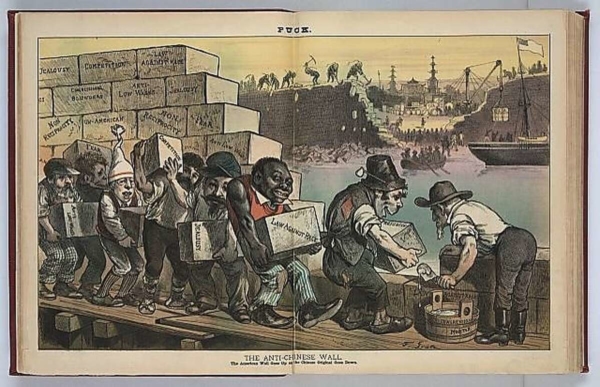

Scapegoating Politics: How Fascism Deploys Race, and How Antiracism Takes the Bait

That larger, more insidious effort and its objectives—which boil down to elimination of avenues for expression of popular democratic oversight in service to consolidation of unmediated capitalist class power—constitute the gravest danger that confronts us. And centering on the racial dimension of stratagems like the Cantrell recall plays into the hands of the architects of that agenda and the scapegoating politics on which they depend by focusing exclusively on an aspect of the tactic and not the goal. From the perspective of that greater danger, whether the recall effort was motivated by racism is quite beside the point. The same applies to any of the many other racially inflected, de-democratizing initiatives the right wing has been pushing. With or without conscious intent, and no matter what shockingly ugly and frightening expressions it may take rhetorically, the racial dimension of the right wing’s not-so-stealth offensive is a smokescreen. The pedophile cannibals, predatory transgender subversives, and proponents of abortion on demand up to birth join familiar significations attached to blacks and a generically threatening nonwhite other in melding a singular, interchangeable, even contradictory—the Jew as banker and Bolshevik—phantasmagorical enemy.

Aesthetic judgement after de Duve: Or, what, exactly, did Kant “get right?”

Thierry de Duve is one of very few leading figures in recent art theory to make Kant’s aesthetics central to their theory of contemporary art. But de Duve’s use of Kant is both idiosyncratic and controversial. In what follows I try to figure out what, exactly, de Duve believes Kant “got right,” and whether this is: i) plausible as a reading of Kant and, if not; ii) philosophically coherent, independently of its claims on Kant. Coming to a view on the latter also involves asking whether: iii) appeal to Saul Kripke’s theory of proper names helps or hinders Duve’s case.

Blind leading the blind

Our three authors are all, in very different ways, possibilists. They assume that socialism in some extremely general sense is desirable; but then frame their “what is to be done” entirely by what looks practical in the very short term. But the result in all three cases is practical unrealism: none of these prescriptions are likely to produce anything other than “more of the same” – meaning a labour movement dominated by the right and a left splintered into little pieces, each of which pursues its own “possible” tactics.