The blinkered vision of the leading voices in contemporary race theory when it comes to the politics of the present is also linked to how they misunderstand the past. Because their analyses are primed to search for continuities in anti-Black racism over time, they tend to ignore an equally pernicious and consistent factor in American history—the assault on organized efforts by working people of all races to challenge the power of capital, to evade or undermine the power of the wage relationship and market compulsion, and to harness the power of the state to put the needs of working people above the pursuit of capitalist profits. Ironically, contemporary race theorists’ ignorance of the political economy of “anti-racism” in the past has meant that the conceptual anchors upon which they build their analysis—racial community and racial interest—and the cognate construct to these, “race relations,” are actually Jim Crow era formulations. In their vigorous promotion of these ideas, they can be seen as intellectual architects of the very thing that their scholarship purports to reveal and thereby dismantle—a “new” Jim Crow.

BY nonsite

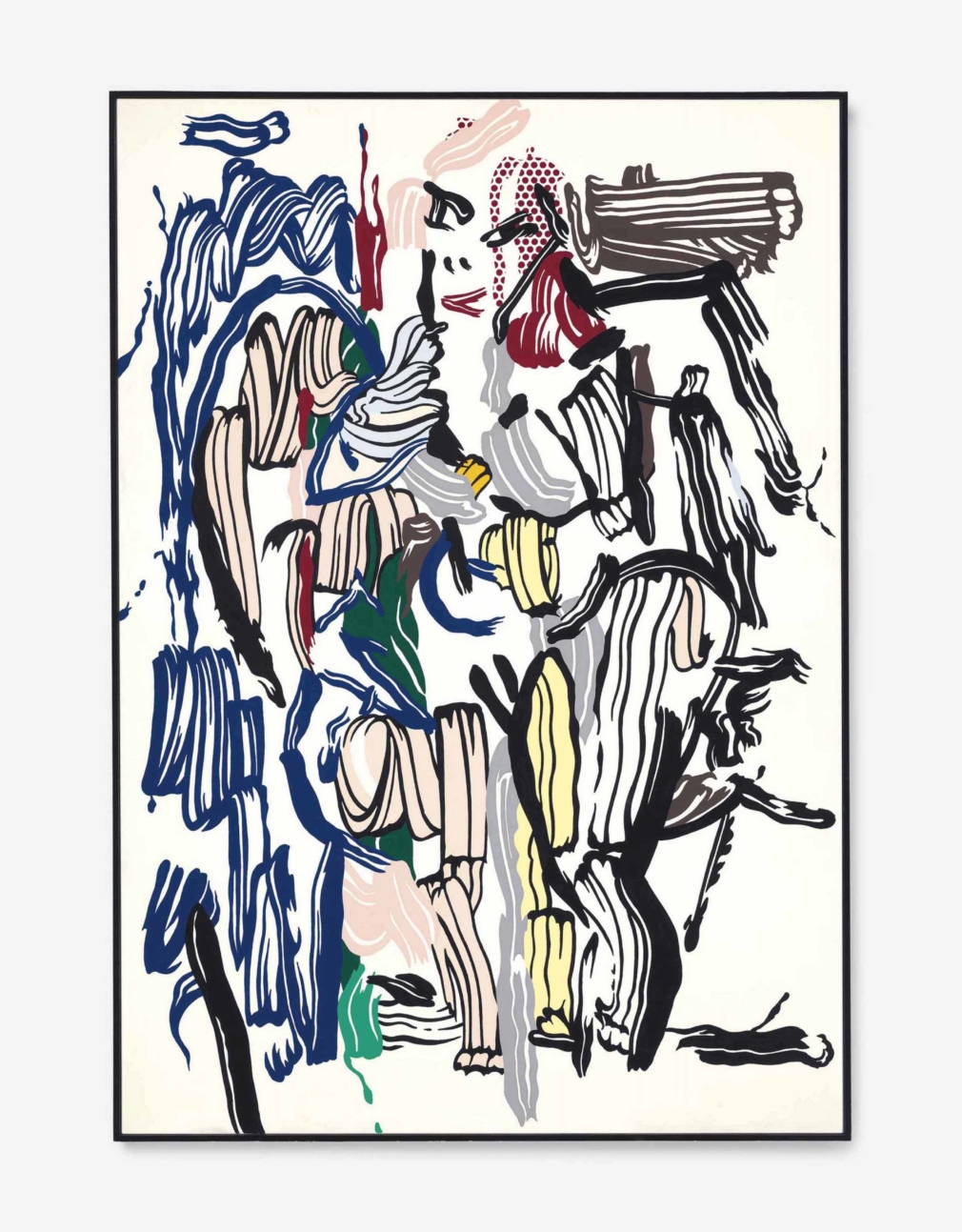

The second in a pair of issues featuring new scholarship and essays on contemporary art, a professional-managerial enterprise. Edited by Elise Archias.

At the same moment during the late 1970s that the Ehrenreichs formulated their theory of the PMC, Art & Language and October were likewise problematizing the growing gap between themselves and the working class and rethinking the relations between art, criticism, theory, and politics. This essay examines the emergence and schism of the Art & Language collective followed by the rise of the October group, focusing on the former’s once-famous 1976 critique of the latter, titled “The French Disease.”

If we take the question about art that is supportive of the PMC as a question about art that is supportive of capitalism, we can see that it’s only incidentally a question about art’s compatibility with the self-understanding of one class rather than another. It’s fundamentally a question about what there can be in art that isn’t reducible to the self-understanding of any class.

Sierra’s tattooed horizontal line conveys the narrative of a modernist outcry that once called for “Workers of the World, Unite!”—or today could call for the people shackled together in debt slavery to unite against neoliberal capitalism. Instead of being ostracized by the burden of carrying a mark for life on their backs, these paid people are united by their tattooed line as much as by their condition as collective subjects of exploitation.

For Clark, the “moment” is not an outlet to the world that would in principle allow a self-absorbed consciousness to find meaning beyond its own interiority. Nor is it a means by which the subject may reach a higher form of mental life. The “moment” is an end in itself.

BY nonsite

The first in a pair of issues featuring new scholarship and essays on contemporary art, a professional-managerial enterprise. Edited by Elise Archias.

BY Chris Reitz

Maurizio Cattelan couches his artworks as clever, if cynical, escapes from labor. But in truth, he rarely gets out of work. Instead, his art enacts a Euro-Atlantic shift from “productive labor” to “creative management,” a shift that he traces (counterintuitively) to the legacy of Marxian theory in Italy.

Warhol’s trajectory as a working-class Pittsburgh boy turned commercial illustrator turned New York art world icon, we might say, primed him to be particularly attuned to the class dynamics of postwar artistic labor, and particularly able to make them visible. But in fact, I’d like to argue, these dynamics are central to the emergence of pop art in general—in a very real way, they are pop art.

None of David Smith’s constructions is ever truly virtualized, truly vaporized, but still, at serendipitous moments, their surfaces spark and crackle with light, and the sculpture’s body is banished, replaced by a scribble, a cipher, a flash. Meanwhile, back in the studio, yet another sculpture is nudged into shape on a much-stained concrete floor.