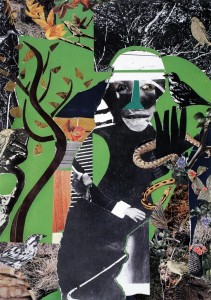

Miró’s Politics

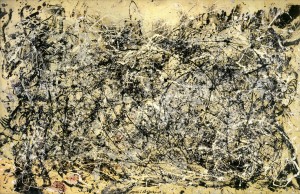

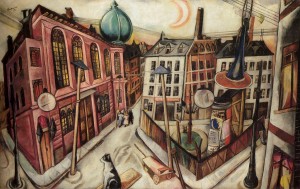

So we have two modes of politics. One that depends on your subject position and one that doesn’t. And we have two kinds of art: one that depends on your subject position and one that doesn’t. And they align themselves, one with the other, according to what they assume about representation and about truth. Which kind of art is Miró’s? Or is it another kind altogether? And what kind of politics does it embody?