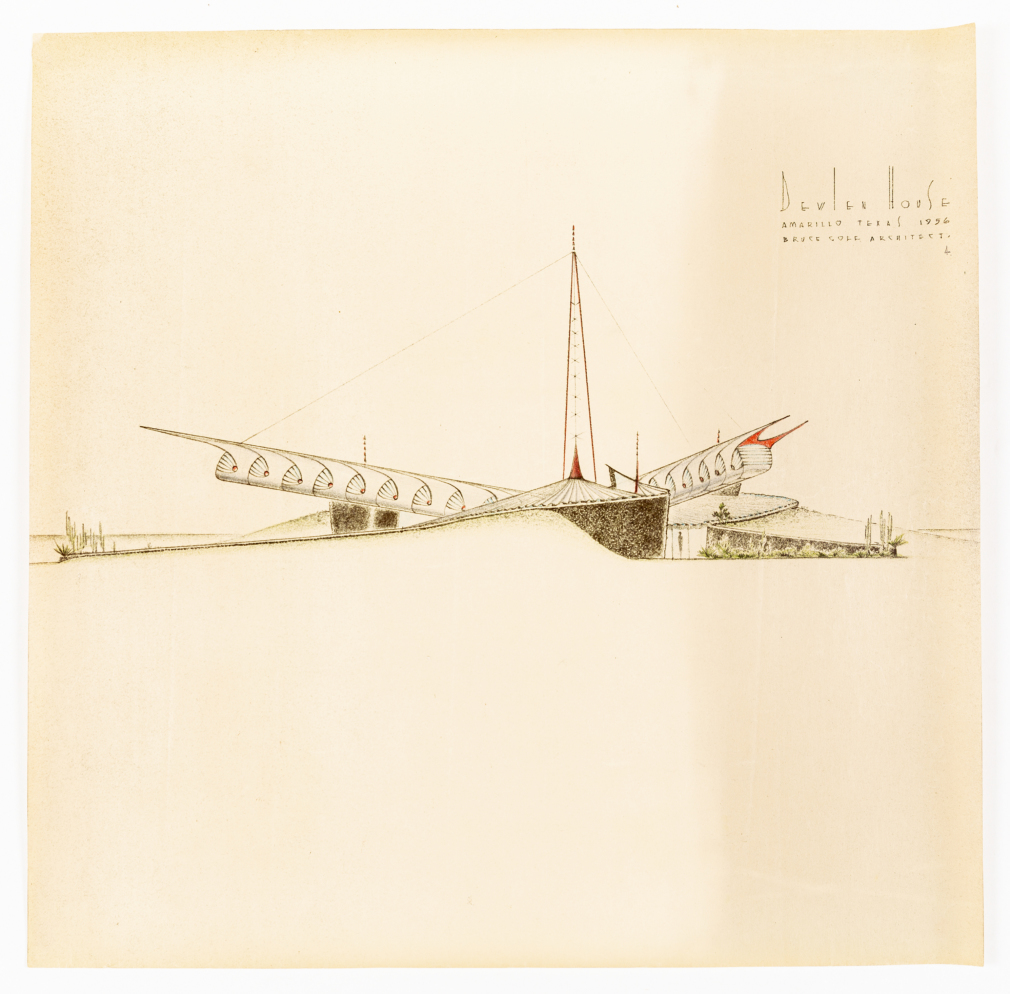

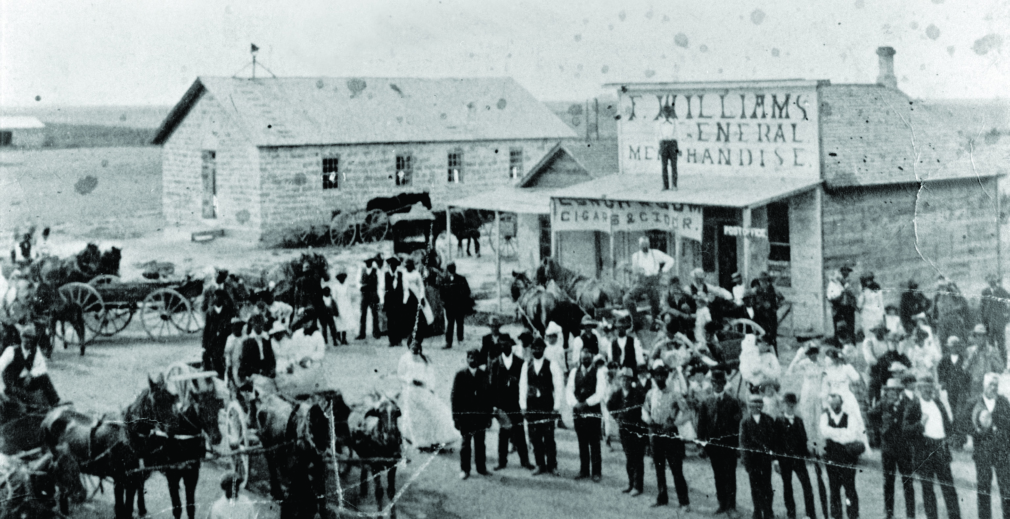

An extraordinary number of aspirational architectural interventions in the wilderness or on its edges began to appear as America moved into the atomic era, as responses to the sublime, the intangible, the cosmic, or the simply inhospitable. They trace a changing, ‘wider’ state of mind towards the earth and the very concept of shelter, as we saw the earth anew from above and contemplated its destruction on a scale unheard of — two perceptual transformations that went hand in hand. The best known of those propositions, such as Saarinen’s St Louis Arch or Soleri’s Arcosanti, work at a metaphysical and material scale of some grandeur. The portfolio that follows – drawn from the collections of Drawing Matter — stands back from those monumental exercises to see what might be learned from more intimate explorations of the architectural path through wilderness and shelter, the proximate and the infinite.

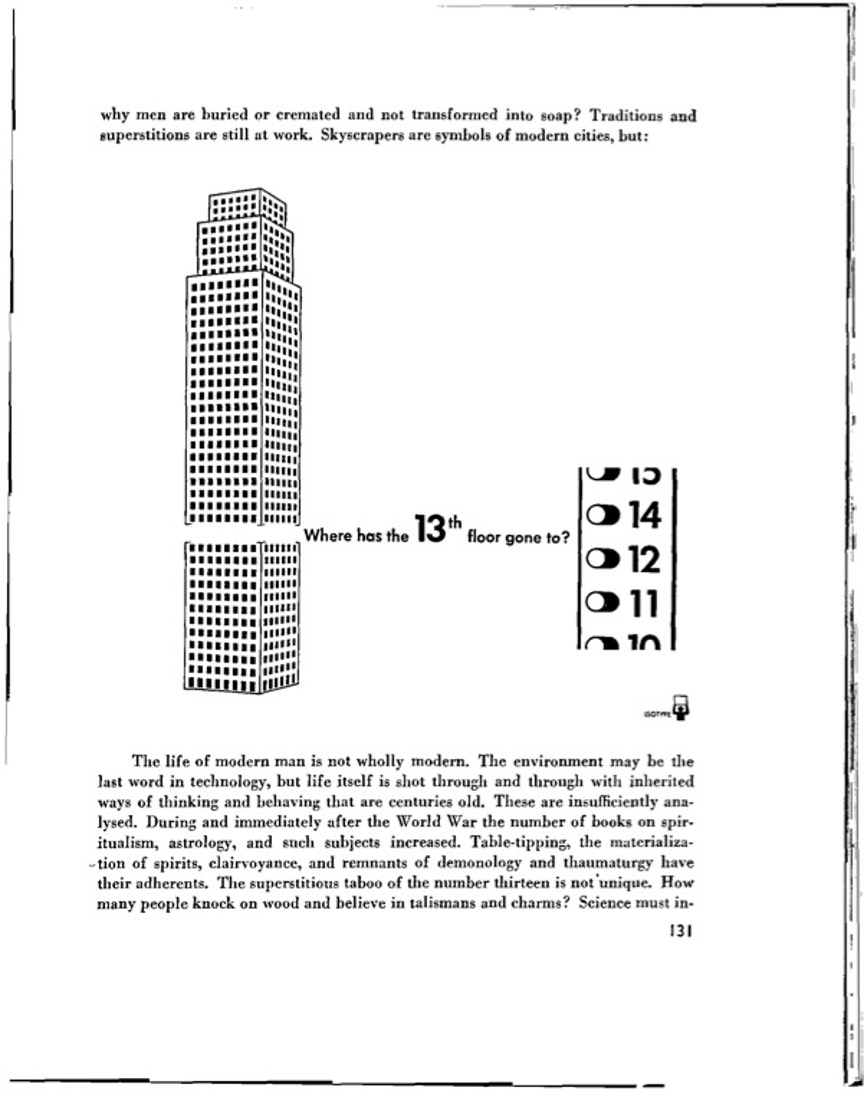

Otto Neurath’s Modern Man in the Making (1939) reflected the practical as well as ideological goals of managerial culture. Neurath rephrased these objectives in his concluding remarks: “men capable of judging themselves and their institutions scientifically, should also be capable of widening the sphere of peaceful co-operation…. The more co-operative man is the more ‘modern’ he is.” Because Neurath was only rarely explicit in his advocacy for Scientific Management, the aim of this essay is to flesh out the underlying managerial goals implicit in Neurath’s proposal.

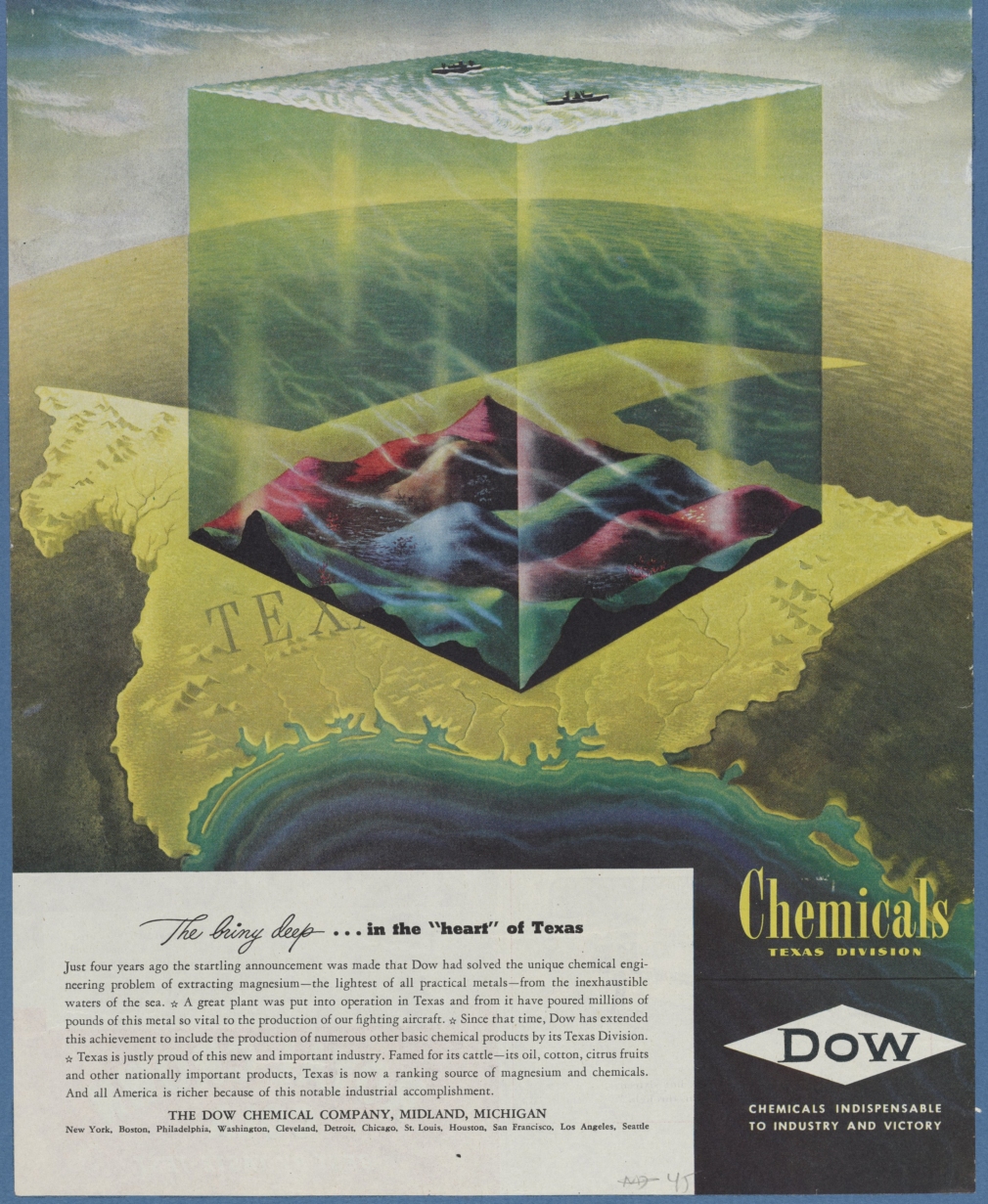

By virtue of its organizational adjacency to his family’s company, Alden B. Dow’s amateur film—documenting a grand, labor-and-capital-intensive feat of wartime resource extraction—offers film and architectural historians a fascinating case study in infrastructural and extractive media. In this case, Dow Chemical’s Texas Division was both building and mediating infrastructure on several scales simultaneously: the production of vital Allied war materials, the provisioning of housing for defense workers, and more profoundly, the making natural and seemingly inevitable of the substrate of the postwar good-life in the products and byproducts of petrochemical modernity. In Freeport-Lake Jackson, modern architecture, moving-image production, and extractive processes of various kinds intersected in the production of value for both for Dow Chemical and Alden B. Dow himself. The result is an example of what I’ll call a “development film,” which bound filmmaking to the work of real-estate speculation.

BY Jenny Breen

Despite the glaring irony, Gorsuch is not talking about judges when he discusses “unaccountable ‘ministers.’” He is instead talking about civil servants in government agencies. In Gorsuch’s view, government agencies pose unique dangers to the American republic. Accordingly, it is essential that courts—and only courts—be tasked with reining in the power of agencies lest the power they wield—to regulate power plants emissions, to establish health and safety standards during a pandemic—destroy the lives of individual Americans.

What the convergence of the American and Central European political discourse seems to prove is that social conflicts in the era of the global market economy are centered around three main axes: (1) distribution of wealth, (2) destruction of the traditional family along with historically prevailing gender roles, and (3) migration and race. Any progressive political project has to, in one way or another, define, frame, and address those clusters of problems, creating a narrative capable of mobilizing and channeling the social desire away from the conservative-populist alley. In this context the only difference between Left and Right is that the latter, starting from the 1970s, became gradually more and more proficient in translating the real social tensions into the phantasmatic language of populist politics.

The Peoplemover does not merely transform what might otherwise be wall-hung or anthology-bound works of concrete poetry into tools for protest; it more fundamentally demands interpretation of what such a transformation of art into activism means in 1968. Solt’s “demonstration poem,” as she calls it, is a revealing engagement with the formal problematics of concretism and the historical contradictions concomitant with the rise of New Left protest politics in the U.S.

BY Éric Michaud

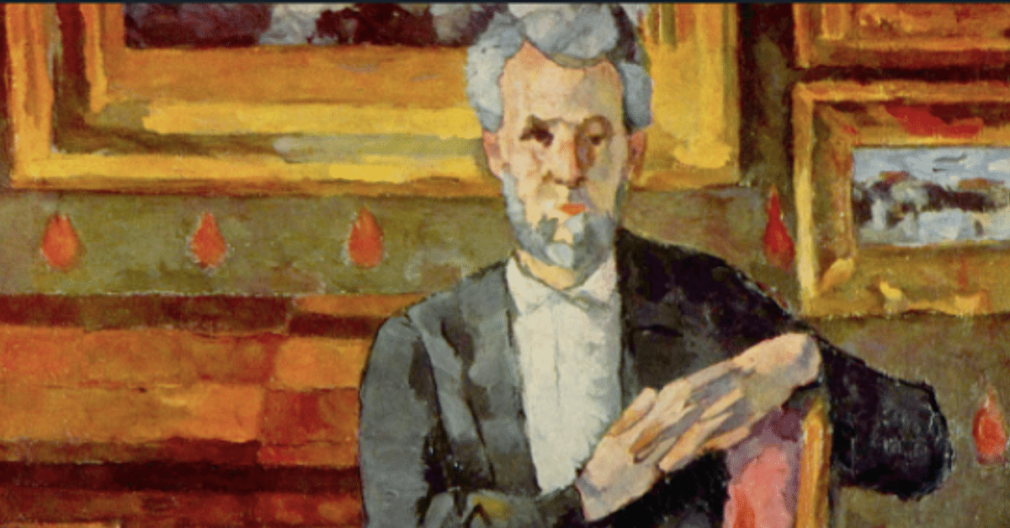

All of Cézanne’s “theory” seems to come down to what he calls “realization,” an operation of conversion that he was the first modern painter to attempt. Critics had a premonition of it, condemning his “too exclusive love of yellow” and warning the public: “If you visit the exhibition with a woman in an interesting position, pass quickly by the portrait of a man by Mr. Cézanne… That strange-looking head, the color of boot cuffs, could make too vivid an impression on her and give her fruit yellow fever before its entry into the world.”

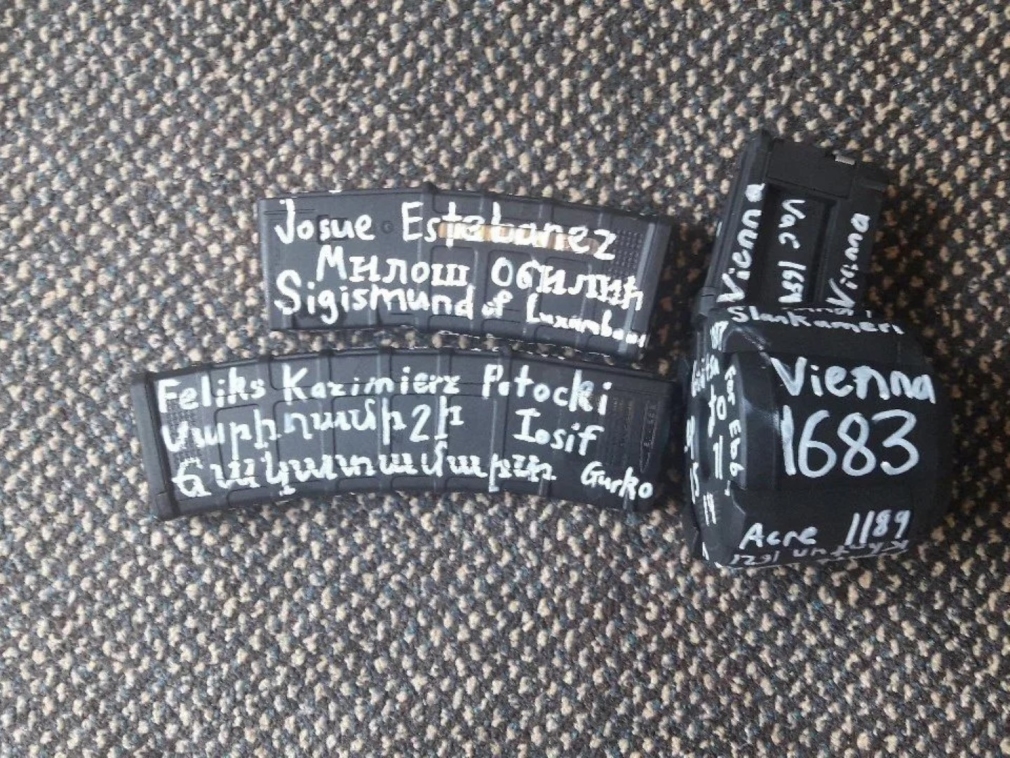

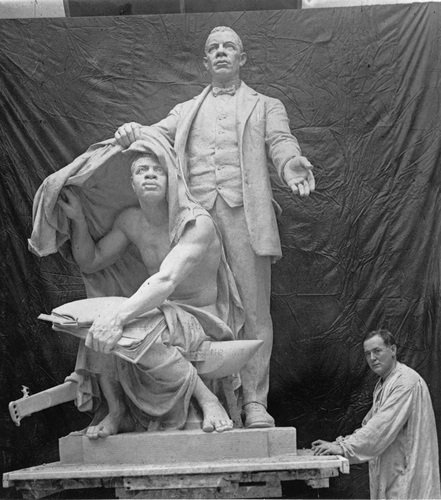

All this makes crystal clear why proponents of race-reductionist politics are so unmoved by criticism based on effectiveness for generating a popular politics or for winning egalitarian reforms at all. Just as with the Bookerite progenitor, developing and advancing a popular politics is not the point at all. It is a politics geared toward bending ears of and currying favor from elements of the ruling class and their gatekeeping minions. The real constituency race-reductionism seeks to address are the “big white men (and women)” who have the power to validate Voices and agendas geared to advance black investor class interests as representing the unproblematic good of the race and thereby use race to do the same thing the ruling class ideologues of militant white supremacy used it to do at the end of the nineteenth century.

The blinkered vision of the leading voices in contemporary race theory when it comes to the politics of the present is also linked to how they misunderstand the past. Because their analyses are primed to search for continuities in anti-Black racism over time, they tend to ignore an equally pernicious and consistent factor in American history—the assault on organized efforts by working people of all races to challenge the power of capital, to evade or undermine the power of the wage relationship and market compulsion, and to harness the power of the state to put the needs of working people above the pursuit of capitalist profits. Ironically, contemporary race theorists’ ignorance of the political economy of “anti-racism” in the past has meant that the conceptual anchors upon which they build their analysis—racial community and racial interest—and the cognate construct to these, “race relations,” are actually Jim Crow era formulations. In their vigorous promotion of these ideas, they can be seen as intellectual architects of the very thing that their scholarship purports to reveal and thereby dismantle—a “new” Jim Crow.

At the same moment during the late 1970s that the Ehrenreichs formulated their theory of the PMC, Art & Language and October were likewise problematizing the growing gap between themselves and the working class and rethinking the relations between art, criticism, theory, and politics. This essay examines the emergence and schism of the Art & Language collective followed by the rise of the October group, focusing on the former’s once-famous 1976 critique of the latter, titled “The French Disease.”