Succoring the West

It was in the year 1683 that the forces of the Holy Roman Empire and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth—mortal enemies up until that point—allied for the first and only time in history in order to defeat their common foe: the Ottoman Empire, believed to have threatened the very existence of the Western world. Polish king Jan III Sobieski, departing from Kraków in late summer, arrived with an army of around thirty thousand soldiers to break the Ottoman siege of Vienna on September 12th; it stopped the Muslim conquest of Europe and began a victorious campaign that pushed the Turks out of large chunks of territory in Central and South-Eastern Europe (mainly the Balkans and today’s Hungary) by the end of the seventeenth century. Christianity was saved, and what seemed to be the unstoppable tide of Islam receded. There are those who claim that the Vienna Relief should be regarded as one of the founding moments of modern Europe, and it’s not only because one of its direct consequences was the creation of the first coffee shop in this part of the world by one of Polish marshals, who found a carriage of coffee while robbing a Turkish camp. One may rightfully argue that it was simply a struggle for control over lands, resources, livestock, and population between two different political entities; however, even at that time it was presented as an apocalyptic confrontation between Good and Evil, a kind of Tolkienesque battle that would decide the fate of the entire world. No wonder that the Pope Innocent XI presented Jan III Sobieski with the title “Defensor Fidei.”

In the Polish context the Vienna Relief plays a very important role—it is one of the major symbols of former Polish glory, of the times when Europe badly needed help and Poland came to the rescue, but above all the symbol of Poland as a European frontier, guarding the civilized world against the dangers lurking behind the borders, ready to flood Christianity with paganism. It plays very well into some defining characteristics of Poland’s national habitus—the combination of an inferiority complex and delusions of grandeur: we were the greatest, the most powerful, the needed; it was us who helped, who sent relief; it is the West that was the helpless and needed support. In this sense, the Vienna Relief is part of a wider mythos, created retrospectively in the nineteenth century when Poland lost its independence and feared losing its identity. Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846-1916), Polish Nobel prize winner for literature—whom Henry Miller called “the dreadful Pole”—was one of the most important creators and proponents of this myth. In his historical fiction novels Sienkiewicz made an attempt to establish modern Polish national identity, casting Poland as the ultimate defender of Europe against alien threats. His most popular creation, The Trilogy, depicts Polish Catholics struggling against the anarchic Cossacks, protestant Swedes, and Islamic Ottoman Turks in the mid-sixteenth century—the barbarians and infidels waiting to crush the civilized world. More or less at the same time, in the late nineteenth century, those who defended the U.S. frontier against the Indigenous people, the Mexicans, and the outlaws became the heroes of public imagination, and tales about them provided the base for American identity. Sienkiewicz himself traveled to the United States in 1876—a trip that included a long itinerary in the American frontier (California, Colorado, Wyoming) heavily influenced his opus magnum, The Trilogy. So, you may think of him as a kind of Polish Karl May, and as a matter of fact, when you see the cinematic adaptation of The Trilogy for the first time, you can’t stop wondering why you are watching this weird western: guys on horses enthusiastically kill the natives but are fighting with sabers instead of colt revolvers.

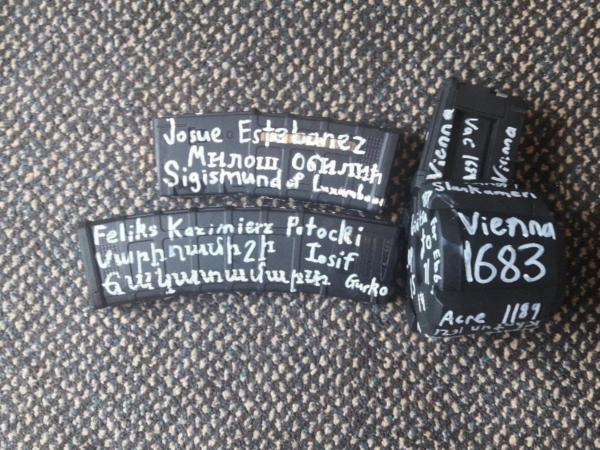

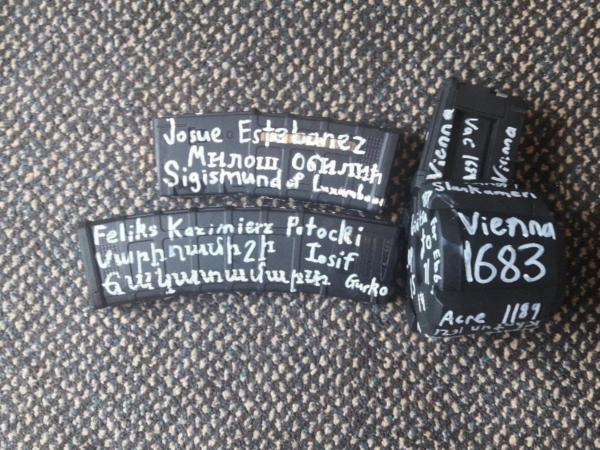

The Vienna Relief has happened to play a role in contemporary radical right-wing narratives: Brenton Tarrant, the infamous shooter who killed forty-three people praying at the Al Noor Mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand on March 15, 2019, mentions the Battle of Vienna of 1683 as an example of the heroic last stand of white European civilization against the mortal threat of Islam. Another Pole appearing in Tarrant’s manifesto and on his weapons was Feliks Kazimierz Potocki, a noble and military leader who took part in the Battle of Vienna of 1683 and was famous for other military expeditions to the Polish Eastern frontier. But that is not all—even though Tarrant was inspired mainly by Serbian and Austrian nationalists and neo-Nazis, he chose Poland as the location for laying a false trail, in his own words, a “red herring” planted into his biography for the secret services to follow after his attack. Three months before the Christchurch shooting, Tarrant visited Poland to take part in a “knighting ceremony” performed by the “Knights Templar Order International.” He wanted to create an illusion (inspired by the Oslo shooter, Anders Breivik, who also claimed to be part of a modern Templar Order), that he belonged to a larger organization, a cabal of heroes united and ready to give their life in defense of the West in the war against what he and people similar to him call the “great replacement” or “white genocide.” In reality, today’s Knights Templar Order International has nothing to do with fighting paganism but is a typical modern con, giving history geeks an opportunity to acquire the title of Knight Templar or Templar merchandise for a hefty sum—murdering Muslims is not really on the menu.1

The conservative fascination with the Ottoman-Habsburg wars spanning three hundred years from the early sixteenth to the late eighteenth century and with other historical conflicts with the Ottoman empire is by no means limited to radical fringes of extremist terrorism. The cover of the last issue of the The European Conservative2 —an online journal that had the late Roger Scruton on its Advisory Council—features a reproduction of an 1859 painting, “The Self-Sacrifice of Titusz Dugovics” by Alexander von Wagner (1838-1919), which depicts a scene from the 1456 Siege of Belgrade. Today’s Poland—ruled by a conservative-populist government of Law and Justice hostile to immigrants, especially Muslims—along with Islamophobic Orbán’s Hungary have become examples that American conservative-populist politicians and pundits put forward for other Western societies to follow, as if it were a kind of reenactment of the historical struggle on the Eastern frontier. After Joe Biden counted these two countries together with Belarus among “totalitarian regimes” during his electoral campaign in 2020, a plethora of voices arose to defend the noble example of Poland and Hungary as “successful countries that insist on maintaining their national identities and traditional values—and doing so with the use of democratically earned political power,” as Gladden Pappin wrote in Newsweek.3

What are we to make of these surprising demonstrations of admiration for semi-peripheral countries uttered by elite intellectuals from the very center of the capitalist world-system? Are these just glitches in their discourse, some kind of contingent ad hoc articulations that have no deeper sense nor meaning? Or maybe they attest to some underlying principles of the contemporary world where a long present tilt to the right is slowly evolving towards a full slide into fascism? Let us attempt to answer these questions, sketching what we believe to be populism’s plane of immanence, understood as its fundamental dimension that also includes its apparent ideological oppositions, a kind of cornerstone on which the uncanny edifice of international populist movement is being constructed before our eyes. The immanent perspective that it implies underlines one of the key features of the contemporary right-wing revolt that is often missing from the mainstream liberal accounts: it is not an unexpected result of some external intervention—a kind of deus ex machina—but a consequence of the internal dynamics of late capitalism. So, populism is not any kind of outside—or Other—of liberal democracy but rather an element of its inner, immanent workings.

One might even argue that modern liberal democracies can only be understood through the lens of populism. To put it in Deleuzian terms, we could say that the plane of consistency/plane of immanence of politics today is centered around the notion of populism. It means that the forces constituting it in this particular moment in the history of capitalism create a “space” of possibilities different in structure from the ones preceding it. The neoliberal narrative on the end of history and post-politics used to generate the effect of truthfulness, and for that reason, it was able to induce the masses to affective investments. But now the allure is long gone, and the once hegemonic discourse sounds erroneous and out of touch with reality. To put it in simpler terms, a plane of consistency determines what is possible—that is, what can be thought, said, and done and how can it be thought, said, and done. So, only through analysis of populism not as an exception but as a determining mode of politics today can we grasp the conditions enabling the success of right-wing backlash worldwide. It is here that a comparative analysis of two culturally remote cases of Poland and the United States comes in handy.

The idiocy of global life

Along the lines of the new Middle Ages that we live in, the only truth that can appear in the court of public opinion is the one articulated by jesters. Thus watching South Park has become more than just entertainment. Seen from the peripheral Polish perspective the series has evolved in an uncanny way: some twenty plus years ago, when it started, it was mainly a funny and bizarre cartoon where celebrities transformed into mechanical dinosaurs, and one of the main protagonists got a parabolic antenna installed in his ass by extraterrestrials. In the last decade, more or less from the moment the HumancentiPad was engineered in one of the episodes by vicious product developers working for Apple, South Park has become a kind of surrealistic documentary representing also our own Polish reality in an insightful and troubling way: gentrification, e-scooters, pedophile scandals, political correctness, COVID pandemics, insurmountable polarization of public opinion, police brutality, populism, even Amazon warehouses—all that has become the very core of our daily lives here in Poland. Here we go—the (in)famous global village, one could say. What’s so new or interesting about it? Actually, the change we mean here goes far beyond the pop-anthropological concept of “global village” so often used in media debates.

First of all, what is rarely or never mentioned, when Marshall McLuhan coined the term, he meant not only the shrinking of the social world provoked by globalization and technical advancement but also a reactionary movement from openness and progress towards what could be labeled with the Marxist term “the idiocy of village life”—our social world resembles more and more a village ruled by gossips (in its commodified incarnation taking the form of “fake news”) and prejudices (or “traditional values,” as conservatives label them): “we have seen in this century the changeover from the debunking of traditional myths and legends to their reverent study. As we begin to react in depth to the social life and problems of our global village, we become reactionaries.”4

Yet, there’s another crucial feature: the reversal of patterns implied by modernization theory according to which the so-called developed countries provided a blueprint for all others to follow. Of course, globalization still contains the crucial element of Americanization and Westernization. No triumphalism intended here: the Western civilization certainly has no moral superiority over other cultures; on the contrary, it seems much more ruthless and devoid of ethical limitations as proven by the history of capitalism. There is, however, more and more of a kind of “Polonization” of the global village, a synecdoche of the world becoming more and more like provincial Poland with the patterns of political and social interactions we have known in Central Eastern Europe for decades becoming something like a gold standard of contemporary politics.5

So, it becomes maybe less surprising that even before Joe Biden brought the Polish authoritarian turn to broader light, likening Kaczynski to Lukaszenko, Poland had its place in the discourse of conservative intellectuals, as the public activity of Harvard-based legal scholar Adrian Vermeule illustrates. In the last couple of years, he used the example of Poland as the one to be followed by the U.S. on several occasions. In one of his texts, Vermeule points to what he believes to be a kind of paradox: the liberals seem to be much more upset with deviations from liberal-democratic playbook in Poland or Hungary than they are with complete rejection of democracy in Saudi Arabia or China.6 As a matter of fact, the same paradox can be attributed to the conservative-populist praises of Poland and Hungary as the examples to follow, while Saudi theocracy or Chinese concentration of power seem to be much closer to what the likes of Trump or Farage would like to see installed in their own countries. Vermeule’s answer to his original paradox provides also the explanation for the latter: while Saudi Arabia and China are countries that have resisted in one way or another liberal modernization, Poland and Hungary eagerly embarked on this path in early 1990s after the fall of the Soviet Bloc, and they seem to have voluntarily departed from it in the last decade (Hungary first with Orbán coming back to power in 2010, Poland following with the double electoral victory of Law and Justice in 2015, when it grabbed both presidency and majority in parliament). Traitors for the liberals and converts for the conservative-populist, Poland and Hungary represent a fundamental loss for the progressives and the ultimate trophy for the reactionaries. The fierce anti-migrant stance assumed by Poland and Hungary, rooted deeply in traditionalism and Catholicism, is not only an inherent element of political projects partaken by Kaczynski and Orbán but also one of features that make it so attractive to reactionaries worldwide. One may say it is ironic given the fact that Poland has received more than a million Ukrainian immigrants (sic!) during the rule of Law and Justice,7 however in the age of spectacular populism the Real matters little—what is important is the phantasy: a phantasm of a community of people unstained by multiculturalism, believing in their own values and ready to put their existence on the line to defend them—in other words, everything the Western World ceased to be (and in fact never was).

To be sure: the phantasmatic nature of the right-wing political narratives as such does not bother us. What is troubling is, of course, its content. Phantasy in itself is the very scaffold of any subjectivity, be it individual or collective. As a matter of fact, the problem of the Left is the poverty or even absence of phantasies—while the Right paints sublime pictures of glorious struggle for the most important ideals and a Brave New-Old (that is: retrotopic) World, the Left has remained obsessed with victimhood. Is it surprising that having a choice of identifying with a victim or with a hero, people chose the latter and not the former?

Poland—the Rorschach’s phantasy

It is not the first time for the Western Men of Letters—an older name for people we call “intellectuals” nowadays—to use Poland as a phantasmatic topos, a term designating a place without properties, at the same time an every-place and no-place. From Calderon de la Barca (Life is a Dream, set in “Poland—that is anywhere”) to Alfred Jarry (Ubu the King, happening in “Poland—that is nowhere”), Poland has played the role of a blank canvas onto which one can paint desired shapes, characters, values, or events. Today the same logic applies: the allure of Poland for the American conservatives is made possible mainly by its lack of precisely defined form and content—it seems liberal enough to resemble the Western democracies, with individualism and consumerism, but not too liberal when it comes to worldviews and values; it’s also traditional, xenophobic, and very white but not authoritarian enough to become something scary and despicable, like Russia. And, conveniently enough, unlike Russia, Poland could not easily become a global empire that would ever threaten any kind of Pax Americana, and as such, it offers a safe space for all sorts of reactionary phantasies.

What is, however, the main attractor that Poland possesses in the eyes of contemporary global right is its homogeneity: with almost no people of color visible on the streets, Poland is like a Texan neocon wet dream come true. At the same time, being a member of European Union, NATO, OECD, and other global organizations, Poland is by no means any kind of isolated white men’s Bhutan. Such a situation allows countries like Poland and Hungary to be used as a model or an example of traditional societies immersed in global capitalism, taking full advantage of the free movement of goods but at the same time apparently able to avoid the social costs of free movement of the workforce, the costs that take the form of racial and/or religious tensions and that are going to keep on popping up as long as the job market remains the only mechanism of social integration. Obviously, it is true only on the level of spectacular narrative—in reality a large share of the low-income jobs in Poland is performed by migrants, mainly from Ukraine. But you couldn’t say that looking at people on the street—the skin color is the same. This whiteness seems to be very reassuring for a conservative mind, as it corresponds well with organicism and naturalism of conservative thought, for which society is a natural extension of family mediated through direct associations.8 So, a white Western country is an embodiment of a righteous family, while the very presence of people of color signals some kind of lack of virtue to a conservative mind—after all, in the eyes of the conservatives, there is only one way a white family can have children of color: the mom fucked around. Anti-immigrant sentiment of the Right and its well-known misogynist stance may be connected after all; it is, however, a separate issue we do not intend to explore here.

The alleged social harmony that the conservatives project on Poland or Hungary is utterly illusional. Both the history and presence of these societies are full of divisions and exclusions, while the so-called “traditional values” have little or no influence on the everyday: the Gospel is not the regulating text for any aspect of social life in Poland nor in Hungary. The supposed harmonious past of organic unity of Polish culture and society is a phantasmatic fabrication of conservative intellectuals. The history of Polish serfdom—much harsher than the one in the West and enduring all the way until the late nineteenth century9 —provides an interesting context for understanding slavery: it was all about exploitation and power with discursively manufactured racial difference justifying economical divisions by the means of naturalization. In the case of Poland and most other countries in Europe, the racial narrative—for lack of obvious material differences between supposed races—introduced the notion of “blue blood,” distinguishing the aristocrats (the owners, in Poland: szlachta), from the commoners (the owned). Polish aristocratic elites colonizing Ukraine employed the term “Czern” (“the Blackness” from “czarny” meaning “black”) to describe the Indigenous rural population that they dominated and turned into de facto slaves in the framework of a manorial economy from the late sixteenth century onwards, though there was no real morphological difference that could justify this kind of distinction. Thus race, empirically lacking, was ideologically constructed. The trick allowed the class conflict to be rearticulated in biological terms in order to put the economy out of the picture and to naturalize socially constructed inequalities, seemingly making it impossible for humans to control or alter. One needs to remember that economical exploitation always ontologically precedes the culturally created divisions, like race. It doesn’t mean that the race doesn’t matter, but that it means anything only in the context of economical exploitation. Or, to put it in different terms: for the racist it is the race that justifies the economical exploitation, while in reality it is the economical exploitation that explains race. That is one of the reasons why it is hard to be at the same time materialist and racist.

Learning from Poland: how the neoliberal shock therapy brought about the populist reaction

The sudden admiration expressed by Western conservative intellectuals towards Poland as a noble example to be followed provides a good opportunity to rethink the place of Eastern Europe—and the entire so-called “Communist Bloc”—in universal history. We need to go back to Francis Fukuyama and his (in)famous “end of history” thesis and look beyond it. Let us sketch some main points that could be elaborated in a more systematic analysis.

Winston Churchill claimed—or at least the claim is attributed to him—that Eastern Europe produced more history than it could ever consume. Lack of understanding of our own past seems to truly be one of the key components of our self-unconsciousness. (So, maybe it should not come as a surprise that the most insightful books about Polish history are not written by Poles.) Thus, the story of the 1989-1990 breakthrough is usually interpreted in the quasi-universal and pseudo-deep categories of a confrontation between freedom and totalitarianism. As is usually the case with such neat juxtapositions, neither side is truly what it claims to be. The very term “totalitarianism” is problematic in itself,10 but even if we accept it, what was left of the Soviet Empire was hardly totalitarian at the time. As a matter of fact, starting from mid-1980s the so-called “Communist” Party governments in various countries of the bloc were gradually releasing the ideological corset and allowing for more and more freedom, especially when it came to economic activities. In Poland, for example, the bulk of pro-capitalist market reforms were introduced by the two last “Communist” governments in the late 1980s.

The year 1989 was a genuine breakthrough not so much in terms of actual basic practice but rather in ideological superstructure: it spelled the end of what Fukuyama believed at the time to be the last genuine alternative to the combination of the free market and liberal parliamentarism. As he put it in the original article that was later developed into the book:

the passing of Marxism-Leninism first from China and then from the Soviet Union will mean its death as a living ideology of world historical significance. For while there may be some isolated true believers left in places like Managua, Pyongyang, or Cambridge, Massachusetts, the fact that there is not a single large state in which it is a going concern undermines completely its pretensions to being in the vanguard of human history.11

Ironically, already at that time there were two other ideological alternatives to liberalism operating in various parts of the world, also within the former Soviet bloc: Islamic fundamentalism and populism. The latter appeared in Poland almost at the very moment when Fukuyama spelled his failed prophecy, in the years 1990 and 1991, embodied in the populist figures of Stan Tyminski and Andrzej Lepper.

As Loïc Vacquant rightly pointed out,12 the actual practice of existing neoliberal regimes is far from neoliberalism’s declared ideals and consists not of dismantling the power of the state but rather of its transfer from the left hand (symbolizing care, protection, redistribution, etc.) to the right hand (coercion, control, incarceration, etc.). In the early 1980s this approach was favored by the regimes of Thatcher and Reagan, who introduced a series of reforms to the social and economic policies in their countries; however, it was only in remote places—mainly in South America, such as Bolivia or Chile—that neoliberal orthodoxy could have been fully applied in all its viciousness at the systemic state level. It’s here that the crucial role of the former Soviet Bloc comes into play: not only a viable systemic alternative to free-market capitalism was removed from play, but what was installed instead had nothing to do with welfare states existing at the time in Europe or North America. It was rather a kind of market fundamentalism postulated by the neoliberals—like Harvard-based economists Jeffrey Sachs or David Lipton—combined with extreme lack of any form of social protection. After the initial experiments in South America, it was at that moment that not only a single country but an entire bloc was reformed according to the neoliberal playbook. In Hegelian terms, it was a repetition that paved the way to universalization: neoliberalism got transformed from a possible alternative into the one and only possibility to which there was no other alternative.

Neoliberalism has always been, of course, much more than just an economic doctrine. As every major political ideology, it also implies a kind of social ontology and, along with it, a certain mode of construction of subjectivity. It was one of the basic and most dangerous illusions of (neo)liberalism to believe that its highly individualistic and atomized mode of subjectivity that may be very attractive for some segments of bourgeoisie would necessarily have a general appeal to any member of any society. We do not need to assume that people have a widespread desire for voluntary servitude to grasp the reasons for basic rejection of the (neo)liberal form of subjectivity. Of course, many—if not all—see individual autonomy as a value, however in the wake of neoliberal precarization accompanied by generalized uncertainty, other needs such as security, belonging, and a sense of support one gets from his or her community eventually come to the forefront, as they did in Poland and in the U.S. as well, despite a quite different social and cultural background.

By the way, it’s worth keeping in mind that historically the model of subjective autonomy and individual emancipation was closely linked to the position of the successful bourgeois “entrepreneur of the self,” to use the term coined by Michel Foucault. The liberals who seem to have truly believed that the buzzwords such as “freedom,” “liberty,” “decency,” “rationality,” etc. serve as the best guiding principles for political action, no matter what class position you occupy and what your daily life looks like, are joined in their naivety by a stream of supposedly left-wing intellectuals, as epitomized by a ridiculously unrealistic concept of the public sphere put forward by Jurgen Habermas. The latter, as observed by French philosopher Alexandre Lacroix, may be useful when it comes to describing a communicational practice of internet chatbots but not real humans in an alienating, humiliating, and deeply disturbing reality of neoliberal capitalism.

It is precisely around the question of the common and community that the current concatenation of conservatism and populism has developed, and it is what seems to be the most troubling in its evolution. As we mentioned before, Poland, right after its exit from the falling Soviet bloc in 1989 and the application of neoliberal shock therapy in 1990, developed a strong populist reaction. It was, however, unanimously rejected at that point by both the liberal and conservative milieus within the mainstream of Polish political life (and those were the only groups we had—the Left was nonexistent in institutionalized politics until 2015 and even at that point it could not articulate anything more than a very moderate, social-democratic project). Populism was rooted in formalized political life; however, it was constantly present on the level of social reality, enjoying between 10 and 20% of electoral support.

At that—that is, in the 1990s—both liberals and conservatives in Poland were equally neoliberal: they firmly believed in the orthodoxy of the free market and judged any developed social policy as a form of clandestine communism, the ultimate danger to be avoided. A symptomatic break happened in Polish politics by the end of the 2000s. Law and Justice came to power for the first time in 2005; it had, however, a fundamentally different approach to the social question than it has nowadays. They were at the time just a regular neocon formation, George W. Bush-style, combining a reactionary approach to the matter of mores and values with unquestioned enthusiasm for the free market. They even took it to a new level of absurdity: after showing in their electoral spots an emptying refrigerator and blaming the government for growing poverty, they not only appointed the chief neoliberal from the rivaling Civic Platform the Ministry of Finance in their cabinet but voted to abandon the uppermost tax bracket, bringing the highest income tax from 40 to 30%, and to get rid of inheritance tax, making the transfer of wealth inside the closest family members totally tax free (all these regulations have not been changed so far). They had the same nationalistic, xenophobic, misogynistic, and homophobic agenda as they have today; it was, however, not enough. Their government was rejected in 2007 in the early elections that they themselves called in an attempt to get a bigger parliamentary majority. As the good old anarchist slogan goes: you can’t put nationalism into a pot to cook a soup with it.

That so-called “first government of Law and Justice” was formed with the chief Polish populist party Samoobrona (meaning “Self-defense”)—a rural political formation resembling quite a lot the American Populist Party of late nineteenth century, though their leader had much worse looks than William J. Bryan.13 Though that government failed after only two years in power, it marked a turning point for Polish conservatism that pushed it in a completely new direction: they discovered the political beauty of the social problem. They were defeated in the 2007 elections; however, they managed to devour the populist electorate of Samoobrona, compromised by a series of scandals (at least to some degree fabricated by the secret service controlled by Law and Justice during that period). They seem to have realized at that point something that the Polish liberals have not understood until today (let’s just hope that Joe Biden is going to be smarter in that respect, but a lot indicates he won’t be): the material question (the problem of material security)—combined with the community question (the need to belong to a group larger than just yourself)—is the best basis for doing any successful and stable politics in the reality of decaying late capitalism. The problem of the Polish conservatives before that breaking point was that they only catered to the latter and not the former, while the so-called New Left (the likes of Corbyn and Sanders) until today seems to understand only the former and not the latter. It is only the contemporary conservative populists that understand the equal importance of both, and that is the simplest answer to the question why they are winning.

An interesting and important issue arises here: to what extent is this social turn within conservatism just an appropriation of the original program of the Left? Maybe right-wing or conservative populism is just a buzzword used to discredit the new manifestation of old socialist ideas? It is a tricky phenomenon, and we may only attempt to answer that question in the Polish context. It is for the reader to judge if it corresponds to the situation in her country. There are two major core features of Polish conservative populism that, despite the emphasis on solving social problems, clearly differentiate its program from socialism as it was advocated by the working class throughout the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. First of all, it seems that the goal of Polish conservative populists is to solve social problems via market mechanisms. As it was neatly expressed by Antoni Maciarewicz, one of the key figures in the ranks of Law and Justice, their aim is to build a “private welfare state”: instead of strengthening and developing public institutions that provide basic services such as healthcare or education for free to the general public, they prefer to rely on cash transfers to individuals in order to help them in seeking these services privately on the market. This is very different from the socialist solution and has not been a part of the program of the working class that rather emphasized the need to develop high quality public services accessible for free to all. We cannot only look at wages, as socialism has never been about the wages alone but also about developing the public sector. Secondly, fetishization of the working-class identity has never been the key component of socialism. Of course, the socialists distanced themselves from classist disdain for the poor; however, the idea of advancing in social hierarchy away from positions traditionally occupied by the members of the working class has always been one of key elements of socialism. It is probably the most visible in the support for women’s emancipation and anticlericalism that socialism traditionally comprised. Surely, not everyone was as radical as Marx, who believed that the key and distinctive feature of the proletarian revolution was its ambition of not transforming the world in the image of proletariat—as it would have amounted to mimicking the bourgeois revolution that aimed at embourgeoisement of the world—but to destroy the very position of the proletariat as such by abolition of waged labor. However, socialism never entailed an uncritical affirmation of what the working class treated as the most noble formation in the history of humanity. It always encouraged proletarians to educate and develop themselves in order to stop being proletarians. It also praised science as a tool of emancipation from material constraints. Conservative populism, at least in Poland, takes precisely the opposite position, telling people that they are perfect the way they are despite the progressives lambasting their superstitions and obscurantism (the support that the anti-vaccine movement and the denial of human-made climate change enjoy in the ranks of conservative right-wing populists are just the most obvious examples) and thus instilling what is presented as “the traditional popular identity.”

The populist desire

The combination of cultural chauvinism and material redistribution is the most troubling element of contemporary conservative populism, and in this respect, the U.S. and Poland seem to be identical, as the discourse of Adrian Vermeule clearly demonstrates. Gilead is just around the corner (mind the uncanny insistence on the ecological in his argumentation). It is that vicious bind that marks the slow yet steady drift of conservatism towards fascism and may very well underpin the populist regimes for decades to come. Donald J. Trump may never get it because of his deep disdain for the poor that limits his cognitive horizon (not very wide at the start, to be honest), but Trumpism is very well poised to evolve towards a model of welfare chauvinism that characterizes European continental populism (you can find it in the discourse of the French Front National or the German AfD): let them perish while we thrive. It taps very well into something that may be labeled as a “populist desire.” We believe we should approach populism in the very same way that Wilhelm Reich approached fascism almost a hundred years ago—the masses were not tricked or manipulated into supporting the hateful and violent regimes; on the contrary, they genuinely desired what these regimes had to offer. It is that desire that needs to be explained and not denied with some pseudo-critical use of concepts such as “false consciousness” or “ideological interpellation.” It looks like the wretched of the Earth of Western/developed/core countries made a deliberate choice: instead of uniting against the rich in an attempt to dispossess them of the unjustly appropriated share of the commonwealth, they have decided to organize in order not to let anyone poorer migrate to the zones of planetary accumulation (Europe, the U.S., and the rest) to get a share in what is left of the welfare state. If it sounds like an elitist classism—blaming the poor for their immoral composure—let us quickly add that however unheroic it may look, it is a rational and pragmatic choice in the ideological landscape—or rather wreck-scape—left after the neoliberal assault.

The populist desire is what gives global consistency to the plane of immanence of contemporary populism. To grasp the nature and origin of that desire, we need to look at our present predicaments from a historical perspective. This is a task of utmost difficulty for the mainstream of public debate—as argued by Frederic Jameson, the postmodern world is devoid of temporal dimension and can easily conceive of itself only in spatial terms. However, we need to approach the populist desire in a genealogical way, and thus, the temporal aspect is indispensable. Let us sketch its very outline, as anything more is not possible in the limited space of an essay.

The twentieth century had undoubtedly seen the largest attempt at egalitarian—or at least equalizing—distribution of wealth ever undertaken in the known history of humanity. It was marked by two waves of progressive struggle and reactionary regress, the second one delivering us to the perils of populism. The first one started with social unrest and revolutions of the first half of the twentieth century. The most well-known was, of course, the October Revolution. However, it was preceded and followed by others; some of them were successful, like the Chinese Communist Revolution, others not, like the 1905 Revolution in the Russian Empire or the German Revolution of 1918-1919. Whatever the direct result of any of them might have been, their very occurrence, combined with two major wars, changed the trajectory of the capitalist world-system. None other than John Maynard Keynes watched closely the developments of the Bolshevik Revolution and argued that the capitalist countries needed to limit the scale of exploitation if they wanted to avoid the same fate.14 It is worth noticing that the brutal repression of the revolution in Germany delivered the German society to the forces of fascism—the rise of the Nazis under the leadership of Hitler started as early as 1921; Italy witnessed the same phenomenon with Mussolini evolving from a communist into a fascist in the same period. “Socialism or barbarism” it was then, as Rosa Luxemburg famously proclaimed.

The so-called three glorious decades—roughly, 1945-1975—saw welfare states installed in many Western countries. Contrary to the Maoist conviction “the worse the better,” the advancement of social rights and redistributive politics undertaken under the leadership of social democracy did not send the repressed into a slumber but rather enticed more revolt, which reached its peak in the stormy 1960s. It was at that point that it became clear that further advancement of radicalism would put capitalism under mortal threat and that the power of the working class achieved thanks to collective struggles and unionization had to be broken.

It was in those circumstances that neoliberalism was born and came to prominence as a handy way of crushing progressive movements. If we look for a turning point, it would be the 1973 Chilean coup d’état carried over by the U.S. in order to stop radical social reforms undertaken by the government of democratically-elected president Salvador Allende. The entire logic and rationale of the neoliberal counter-offensive was to stop the progress of labor in controlling capital. Thus, of course, the first practical enemies were the unions, and the ideological enemy was the very concept of class as such. This double-edged sword was supposed to eradicate two collective focal points of progress: trade unions on the level of practice and the notion of class in theoretical investigations, as those two were accurately judged the main threats to uncontrolled accumulation. The sad truth is that neoliberalism succeeded: unions were effectively dismantled, while the concept of class got eradicated from the mainstream of both public discourse and social science, replaced by apolitical theories of stratification and modernization.

At the same time, neoliberalism found a convenient ally to fill the void left by collective identifications: the notion of tradition with its three collective pillars—nation, family, and religion. Natura horret vacuum, and so does the human being, thus something had to be found to fill that gap. It looked like a perfect plan: instead of union organizing and class analysis, patriotic commemorations, religious celebrations, and family reunions posing not only as no threat to the accumulation process but even as very beneficial for it, as the sphere of nation, religion, and family is not only hierarchical but also hostile to communism, which aspired to eradicate them to a greater or lesser degree.

In those attempts the neoliberals were the ultimate postmodernists, as they apparently believed that there is no hard kernel of reality that could not be covered with the veil of ideology. History proved them wrong: what comes back in the twisted and perverted welfare chauvinism of the populists is the repressed Real of material predicaments. One cannot blame the dispossessed for looking for some kind of shelter from the harsh reality of the free market and for not wanting to be lonely elementary particles. We need to remember that as long as the progressive struggle was possible—so, more or less until the end of the 1970s—the working class organized within its confines. There were many radical ideas around; they were not, however, chauvinistic and misogynistic. The rise of the radical right-wing institutionalized in political parties coincides with the rise of neoliberalism in the 1980s. The French sociologist Didier Eribon neatly demonstrated this link in his auto-biographical book, The Return to Reims, which we have no space to summarize here. Thus, the three crucial elements of the populist-conservative propaganda—religion, family, and nation—should be interpreted as a kind of corrupted common, a lie and illusion in which we can see the truth itself: the very material and animalistic need of a human being not to be left on its own in the times of danger and peril.

The modern history of Poland provides another illustration of the same pattern with slightly different timing. The revolt of the 1960s had no counterpart in Polish history; however by the late 1970s workers’ self-organization gave birth to a truly fascinating and genuinely progressive movement of Solidarity.15 It took the form of a trade union and amassed ten million members, one fourth of the entire population of the country. Just before it was dismantled and repressed with martial law, introduced in December 1981, it formulated its program of a “self-governing republic” that the Polish “Communist” Party rightly characterized as “anarcho-syndicalist deviation,” as it fundamentally affirmed democratic and horizontal self-organization.

The Polish transformation of 1989-1990 is sometimes portrayed as the ultimate victory of Solidarity over communism. This is, however, a major manipulation. The neoliberal reforms enacted by intellectual oppositionists in 1990 not only had nothing to do with ideas of Solidarity but went directly against them: instead of socialization and democratization, we received privatization and plutocracy disguised in the ideological construction of the “free market economy.” Solidarity was defeated and, as mentioned before, at the very same moment in the years 1990-1991, Polish populism was born in the figures of Stan Tyminski, Andrzej Lepper, and his Samoobrona party—established in January of 1992, the very same one that formed the government with Law and Justice in 2005, only to be devoured by it in the populist turn of Polish conservatism, which paved the way to its current dominant position in Polish politics.

Culture does not matter, cultural capital does

Obviously, what we are dealing with here is a class conflict being displaced and played out in symbolic registers. The question is further complicated, especially in the Polish context, by another important factor: highly unequal distribution of cultural capital. We are aware of controversies surrounding the very notion of cultural capital; however, we do believe it may be quite well integrated in the framework of materialistic analysis of both individual and collective subjectivities. Materialistic approach to subjectivity should not be reduced to a purely monetary-economic dimension; it should rather be a materialism-of-a-form-of-life where processes and factors of an immaterial nature—like knowledge or cultural competence—are never devoid of consequences (or correlates) on the material level. One’s cultural capital determines, for example, what and how one eats or how much one cares for one’s body: though it’s much better for your health, a vegetarian diet does not need to be more expensive than eating meat-based fast food—you just need to have enough education to understand it; yoga classes may be expensive, but one may also do yoga with YouTube videos for almost no money at all. A lot of outdoor sports require very little expenses. Many people harm themselves by eating junk food and doing no exercise at all because of how they are limited by their habitus, to use the core concept of Pierre Bourdieu. Thus, having accumulated low amounts of cultural capital has a detrimental effect on one’s functioning on a very material level.

What’s more, there is a key issue linked to cultural capital that has an enormous influence on contemporary politics: the question of recognition. Bourdieu was quite right in observing that there is a part of the dominant class that may not be extremely well off when it comes to material wealth; however, they enjoy a lot of prestige due to their way of life (or the kind of form of life/subjectivity that they represent): their style, their taste—when it comes not only to food, but also to art and culture in general—their knowledge, their opinions, the values they represent, etc. Obviously, Fukuyama is quite wrong in his Hegelian (or rather Hegelian-Kojèvian, as his approach to Hegel is heavily influenced by Kojève) thesis that the struggle for recognition is the ultimate factor explaining all of history. However, it makes little sense to deny that this struggle is a real phenomenon and that it goes beyond pure material wealth as such. It is particularly true in the political landscape of identity politics that we live in—the kind of political practice revolving mainly around the question of prestige and recognition.

While material predicaments are key for understanding the support populism enjoys in lower classes, cultural capital is the main factor that determines the behavior of the lower middle class—or the petite-bourgeoisie, to use a better term. As we know from both Marx and Reich, it is the most problematic and reactionary class—the diagnosis proven by its enthusiastic support for reactionary populist governments around the world. Poland provides a great example of how reactionary conservatives thrive on the desire to be recognized, which is the most frustrated of all the needs that the petite-bourgeoisie possesses.

For historical reasons, cultural capital plays an elevated role in Polish society: transmission of material capital has always been very limited in the Polish context due to the country’s turbulent history; what mattered the most was the preservation and transmission of cultural capital, which the aristocrats made into the very base of their collective identity from the end of eighteenth century onwards. While the post-war Bolshevik experiment was oriented on the emancipation of those who had little cultural capital, after 1989 the old divisions resurfaced: the liberal elites not only reaped the benefits of economic transformation while not having to pay a big price for it (as opposed to workers who were decimated by the neoliberal shock therapy), but they also usurped the role of cultural hegemony, keeping the subjugated classes under check with the use of discursive tools such as shaming or building distinctions of style, taste, and look. The key dimension was how much one managed to fit the modern European/Western standard of behavior that was equated with being civilized as such. Polish sociologist Piotr Sztompka came up with the notion of “civilizational competence” that was allegedly lacking in many segments of Polish society. Those who did not fit this new “civilized” norm were judged to be kinds of Asian barbarians—“a basket of deplorables” to use Hillary Clinton’s (in)famous expression. This discourse was particularly popular in the milieu of Gazeta Wyborcza—the most important Polish daily ran by Adam Michnik, one of opposition intellectuals of the 1970s and 1980s. (Think of it as the Polish equivalent of The New York Times.)

This key trick that allowed Polish reactionary populists to grab power in 2015 and to keep it ever since was their ability to put these two elements on one political puzzle: to cater to the materially deprived with the promise of social policy—on which they delivered, if not entirely then at least to a greater degree than any previous government—and to offer the humiliated lower-middle class a feeling of recognition. The latter was achieved by a combination of positive and negative policies: praising “traditional, Polish values and culture” (with which that class feels much more at ease than it does with the high standards of Western modernity) while expressing strong criticism or even hatred for the liberal intellectual and cultural elites. So, it has been a community of love as much as the one of hatred; in many cases hatred proved to be more important: those who vote for populist politicians feel despised by the same elites that also despise those populists politicians and vice versa; the liberal elites are judged a common enemy by the populist politicians and their voters. It is for this reason that a plethora of scandals surrounding populist politicians had literally zero effect on their popularity. Or even more, they might have made them more popular. In this respect, the U.S. and Poland do seem very similar—the more the liberal media attempt to discredit Trump or Kaczynski, the larger support they enjoy from “the people,” as the same media have also tried to discredit “the people” by denying them recognition and equating them with “a basket of deplorables.” It is a logic of enjoyment that goes beyond any logic of argumentation and makes all empirical evidence of corruption and disgrace futile or even counterproductive.

How democratic is populism? How democratic is democracy?

There’s an interesting question that arises here and links to the attempt to rethink the very basic nature and value of democracy that seems to be present on both sides of the political divide: the (neo)liberals claiming that populism is anti-democratic and boils down to a glitch in the system and the conservatives, like Vermeule or Pappin, who claim that the white/Christian identitarian turn is a result of quite a democratic revolt, however non-liberal it may be. Is the populist desire that we sketched above the sentiment of the majority?

It may be claimed that any attempt at rational explication of the success of conservative populism is doomed to failure because a lot of social research demonstrates that whatever grievances those who support populists may have, they do not correspond to the situation of “an average citizen” or the “majority of people.” It is, for instance, argued that Poland has gone through a period of spectacular economic growth—between the years 1992 and 2019, Polish GDP grew in every single year without even one period of recession. Obviously, what such an argument misses is precisely the question of class positions, which gets obfuscated by the (mis)use of statistics that—as is the case with GDP—only show aggregated numbers telling us nothing about who gets what share of the wealth being produced. But even if we include the distribution factor, it may look like something does not add up in the case of Poland: it is not true that the majority of Poles are materially worse off than they were twenty years ago. So, why in a democratic system with no major electoral irregularities is power grabbed by those whose politics are fueled by resentments and grievances?

To tackle this issue, we need to address the very core question of what contemporary “democratic” regimes really are. We have now internalized the liberal ideology so much that we tend to equate democracy with republican order—that is, the rule of governments supported by parliaments elected in the framework of the so-called “free mandate.” The latter is opposed to the imperative mandate whereby representatives are bound by instructions from their constituencies and can be recalled if they fail to comply with them.16 It is not technically correct to assert that national assemblies express, mirror, represent, or reveal the mythical “will of the people.” As even moderate but honest theorists of democracy—such as, for instance, Joseph Schumpeter—were quite aware in the moment of elections we do not express our will but only our consent to be ruled by this or that politician. We intuitively understand the difference between “will” and “consent”: it is not the same thing when something happens because we want it to happen or when we just agree for it to come true.

For that basic reason republican-parliamentary regimes are almost never the ones where majorities rule. These are, rather, regimes prone to be overtaken by the most determined and well-organized minority. It helps to explain a puzzling paradox that goes against the interpretation of populisms as an expression of any sort of popular will or majoritarian values: a ton of social research and polling done in Poland in the last decades clearly indicates that apart from one single issue—the question of immigration—the majority of Poles do not agree with the choices and opinions of the parliamentary majority. There is a secular trend demonstrating that Polish society has been becoming more and more open; the tolerant and liberal approach is gaining more and more support in most cases: the majority of Polish citizens are now in favor of at least civil unions for homosexuals, against having religion lessons at school (68% believe religion classes should be held at churches and not in school classrooms), very pro-EU (with euroenthusiasm at around 80%), and, as we’ve recently learned, very strongly against making the abortion law stricter: only 15% percent of the Polish population support the verdict passed by the so-called Constitutional Court in October 2020 that denies abortion in the case of fetus malformation (we use the expression “so-called” as it has not been constituted in a legal way that even the Constitutional Court itself confirmed). When it comes to abortion, the opinions of the rest split almost evenly between those who think that it should be accessible at will and those who believe that the regulations voted in mid-1990s that allow abortion only in three cases—rape, mortal danger to the mother, or fetus malformation—are okay (around 35% support for both positions), with another 15% who do not care. The support for abortion at will until the twelfth week has been growing in the last two decades. Polish women have abortions on massive scale; it is just happening either in private clinics that are difficult to control or abroad. There are around a thousand abortions carried out in Poland officially every year, while estimates put the real number at somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000. There’s a website—and it’s a totally legal one, not on the Dark Web—where you can get help if you need to have an abortion trip organized.17

So, when it comes to the “mores and values” of the people—a criteria that conservatives like to evoke—Poland is a liberal country. Ironically enough, political development went in precisely the opposite direction: while Poland has been socially liberalizing, it has also become politically more and more anti-liberal. How can this be? Well, those who represent the anti-liberal part of society are not majoritarian, but they are the most determined and the best organized minority, so they can claim power in the republican-parliamentary regime. They are the most determined because they realize that the liberalization of mores and values is a real phenomenon, and if not countered politically, it will soon transform Polish society in the most fundamental way, especially when it comes to the dominant position of the Catholic Church. As a matter of fact, the recent protests around the change in the abortion law proved that the latter has already happened, and we are just waiting for all its consequences to play out. Those were not only the biggest social protests Poland has experienced since the turbulent 1980s but also openly anti-clerical to such an extent that churches had anti-religious slogans sprayed on the walls and were attacked with improvised paint bombs; they had to be defended by squadrons of police and gendarmerie, just like Party headquarters during the martial law in the 1980s. It was one of the most uncanny images that Polish reality has recently produced.

This widespread liberalization makes the Polish conservatives go into panic mode and gives them their determination. Their main advantage comes also from the fact that, as we argued above, they operate within a collective logic that creates a natural platform for organization. Liberal attitudes are statistically more widespread; however, they are also more atomized and combined with more individualistic ways of coping with reality. Modern societies are intrinsically porous, and they always offer “cracks in the system” for those who have enough resources—be they material or symbolic—to just dodge official regulations. You do not really need to take over the state power to behave in a liberal way in Poland, especially if you live in at least a bigger town, but even the Polish countryside has fundamentally changed. It demobilizes the progressive liberals who prefer to just go on individually with their lives, instead of collectively mobilizing against the government. Conservatism is not about individual dodging but rather about collectively imposing your values on others (just like liberalism, of course, but as the content of liberal ideology is precisely about the possibility of dodging, the liberals would revolt when something is imposed on them—like taxes, for example—rather than when they cannot impose something on others). Everything indicates that, ironically, the only way for conservatives to defend what remains from their “mores and values” (“their” because they are not universally shared anymore) would be for them to become liberals themselves and just assume that if they do not support homosexual marriage or abortion, they can very simply not practice them. That is, however, impossible from the conservative standpoint for obvious reasons.

So, the highly conservative minority of Polish society that supports the populists for ideological reasons is not only fighting for their ways of life but also disposing of collective tools to engage in politics and to gain state power within a parliamentary-republican regime. Any sort of political system that allows for translation of genuinely popular “mores and values” into legislation on the state level would block that option. This is the reason why, in order to counter populism, we need to reform democracy itself beyond “the end of history” slumber. Our political lives will be prone to be overtaken by determined minorities like populist conservatives as long as we are stuck within the liberal mode of free mandate and parliamentary representation. Yet, this is a different matter that we shall not explore here.

The plane of immanence or the Obscurantist International

We opened this essay with the question of populisms’ plane of immanence that determines the uncanny yet, as we have tried to demonstrate, far from irrational or unexplainable convergence of contemporary right-wing politics epitomized by the fascination with countries such as Poland or Hungary among American conservative intellectuals. A preliminary hypothesis—which needs more research and elaboration but seems to us to be a good starting point—would claim that this plane of immanence is constituted by two basic elements: the neoliberal experience and an anti-Enlightenment sentiment that fuels the obscurantist reaction.

We have devoted quite a lot of attention to the link between the neoliberal assault on the welfare state and conservative-populist reaction. Paradoxically, this issue, despite being more obfuscated, is also easier to articulate. Neoliberalism has experienced a steady decline of legitimacy since 2008, and nowadays it is rather an insult than a position anyone would like to defend with pride and enthusiasm, as was the case in the 1990s. A small anecdote from the Polish intellectual scene illustrates it quite neatly. Back in 1991, Donald Tusk, at the time just a simple MP, wrote a preface to a volume of essays entitled Neoliberals Facing the Challenges of the Contemporary World.18 Its author, Janusz Lewandowski, was also a neoliberal politician and served as the Minister of Privatization between 1990 and 1993, so he was the person overseeing one of the largest destructions of the commonwealth in Polish history. He had his fifteen minutes of fame in 2011 when, being the European Commissioner for Financial Programming and the Budget, he questioned the human-made nature of climate change.19 When he made the new edition of his 1991 book in 2013, he symptomatically changed its title to Liberalism Facing the Challenges of the Contemporary World. Obviously, he did not need to change what he wrote, as these challenges did not include what we had not realized in 1991, like climate change for that matter. But the fact that even neoliberals avoid the very term is a sign of change in the public discourse.

Obscurantism is quite another matter. Reactionary populists do not hide their disdain for the Enlightenment. When you explore Adrian Vermeule’s Twitter feed and the entire right-wing micro-blogosphere around it, you often stumble upon vicious attacks on the Enlightenment and particularly on the French Revolution, regarded as the epitomization of the Enlightenment’s violence. As attested by various conservative blogs and portals like The Josias,20 Semiduplex,21 or Ius & Iustitium,22 anti-secular religious fundamentalism—the conviction that state law should follow divine revelation labeled as “integrism”—is a position widely held among conservative scholars and pundits. It is something very familiar in the Polish historical context: the disdain for the Siècle des Lumières has been one of the very cornerstones of not only contemporary right-wing populist politics but of our traditional national culture as such. So-called Sarmatism23 defined itself to a very large extent both by the rejection of Enlightenment ideas and by hatred for the bourgeoisie as a social group (understood here in the descriptive sense of “city dwellers”). It was a deeply agrarian formation explicitly hostile to any idea of progress and reform—an attitude that seems to be a feature of many societies dominated not by city culture, as Western Europe has been starting from at least mid-eighteenth century, but by their countryside, as has been the case of Poland, the Southern and Central United States, or Brazil.24

The reactionaries are not the only ones hostile to the Enlightenment nowadays, or to put it in a different way, one can surprisingly find this hostility also among those who cannot be easily labeled as reactionaries at first glance: the avant-garde of academic humanities. After all, critique of rationality and reason has been at the very core of postmodernism since its very inception in the late 1970s. “Logocentrism” is the buzzword of poststructuralist theory, and its many incarnations, especially in the field of postcolonial theory, equate the Enlightenment and modernity with colonial domination. We do not intend to debate here the merits of poststructuralism in its totality, and we would eagerly agree that some thinkers categorized as poststructuralist are surely worth reading as, for example, Deleuze and Guattari. What we are interested in here is not the objective value of poststructuralist philosophy but rather the political implications it has had. Nor do we intend to blame poststructuralist philosophers for what has become of their theories. As demonstrated by the case of Jacques Derrida, they quite often regretted the link established between their work and the politically reactionary melancholy of contemporary “critical” thought.25 What interests us is the use made of poststructuralist ideas in the public discourse and political life. To what extent this remains faithful to the original poststructuralist philosophy and how much it errs as a (mis)interpretation of its core thesis remains a matter for an altogether different investigation.

What is particularly enlightening in this context is the Polish career of the socio-cultural branch of poststructuralism, namely communitarianism as epitomized by the ideas of, for example, Charles Taylor and Will Kymlicka.26 One of the first to praise them in Poland, long before Derrida became the most fashionable philosopher of Polish academic humanities, was a conservative sociologist, Zdzislaw Krasnodebski.27 Already in the early 1990s, he believed that traditional Polish mores and values stood no chance in confrontation with the Western liberal ideology of individualism. He found a useful tool in communitarianism, as it allowed him to claim that ideas such as “progress,” “emancipation,” or “equality” are a part of a certain cultural tradition that Poland never belonged to (an absolutely correct observation) and, as such, have a colonial status (sic!) in Polish reality. So, paradoxically, in order to emancipate collectively as a nation and society Poland needs, according to this narrative, to negate the universal value of the Enlightenment and its ideas of individual emancipation. Krasnodebski welcomed the “fall of [the] idea of progress” (the actual title of his book published in 1991), as he saw it as an opportunity to get rid of the oppressive label of obscurantism, which is attached to practices incompatible with the rationalist ideology of the Enlightenment like, for example, bigotry or demands for adjusting state law to religious norms (the case of abortion is just the tip of the iceberg here). It is hardly surprising thus that Zdzislaw Krasnodebski became a member of the Program Board of Law and Justice in 2004 and represents this party in the European Parliament nowadays. As a matter of fact, he shares the latter position with Ryszard Legutko, another prominent Polish conservative philosopher and a great admirer of Alasdair MacIntyre (makes sense, no?). They both eagerly engage in the populist mission to at least stop and at best get rid of European integration, as they find the process to be a mortal danger to “traditional Polish mores and values.” And guess what—it earned Legutko praises from no other but Adrian Vermeule.28 Welcome to the Obscurantist International!

Conclusions

If a critical reading of populism is to have any merit, it needs to be a reading of a symptomatologic nature. It is in itself intriguing that a formation with such small cultural capital, supported by so few intellectuals (and none of them having really revealing or impressive things to say), has managed to articulate some kind of truth about our social and political reality. It attests to the fact that we are living in times when even the most simplistic, obscure, knee-jerk, and sometimes just silly ideas of the so-called right-wing intellectuals grasp more of the changing actuality than even the most respected functionaries of the hegemonic discourses. (To be fair, we need to acknowledge that some more enlightened liberals have recently become aware of the decline of liberalism.29) The crisis is obvious—the inability of mainstream liberalism and conservatism and leftwing political discourses not only to solve but to even address the real social conflicts of today leaves the gaming field open for anyone who dares to notice them, even if the proposed solutions are not only false but often nonsensical. Think of Jordan Peterson—he is not going to stop the demise of the patriarchy, but his self-help life guides for men at least acknowledge the fact that the form of subjectivity of the modern western male and his position within the society has changed profoundly. Think of Donald Trump even—the claim that all Mexican are rapists is nonsensical, but the fear he was trying to connect to in his voting base was most certainly real. Obviously, the rape fantasy is just a projection, a phantasm covering the actual reason for those once privileged not feeling safe anymore: their work is gone, outsourced overseas or given to foreign laborers, and the world where blue-collar worker was the king in his castle is long gone. The liberals tell them that it is their own fault and that they are not entrepreneurial enough; the conservatives lie to them and assure them that they will bring back coal mines, steel mills, and factories if only given a chance. But what is sometimes labeled “the Left”—and what Alain Badiou rightly called a part of the problem rather than a solution—is the worst because it shames them and makes them feel guilty. And it is so much better to be angry and hate anyone who could be made responsible for the privilege lost than to feel ashamed and guilty while knowing oneself to be a loser at the same time.

Those who are able to connect to the source of the rightwing backlash are much closer to reality than those who just try to expose the grievances and denounce each and every microaggression. That is why they are not only winning but seem to connect to people, whereas listening to the mainstream political voices makes one wonder if they are trying to reach only those who are interested in the confirmation of their own beliefs and ideas. No matter the political allegiance, most of the mainstream opinion pieces today tend to focus on claims of other journalists or academics, whereas the real conflicts tearing the social field seem to be far less interesting or worthwhile their attention.

What the convergence of the American and Central European political discourse seems to prove is that social conflicts in the era of the global market economy are centered around three main axes: (1) distribution of wealth, (2) destruction of the traditional family along with historically prevailing gender roles, and (3) migration and race. Any progressive political project has to, in one way or another, define, frame, and address those clusters of problems, creating a narrative capable of mobilizing and channeling the social desire away from the conservative-populist alley. In this context the only difference between Left and Right is that the latter, starting from the 1970s, became gradually more and more proficient in translating the real social tensions into the phantasmatic language of populist politics. In the end, it is much easier to blame the decline of Western Civilization on the emancipation of people of color, believers of certain faith, and/or women than to try to understand and redesign endlessly complex flows and fluctuations of global capital. In that regard, it is hard to still be surprised or outraged by the global dominance of right-wing politics, always much more into simple solutions than complicated truths.

Let us note on the margin that for anyone who remembers the intellectual and popular climate of the 1990s, the reorientation of American right-wing discourse towards admiration of anti-liberalism in countries like Poland or Hungary is utterly puzzling. When we were young, most Poles wanted to become Americans; nowadays it looks like about half of Americans want to become Poles. Yet this is symptomatic of the uncanny resemblances between the U.S. and (semi)peripheral zones of the capitalist world-system that often go unnoticed. America was the model of modernization for the peripheric, post-colonial countries all around the world, because it was—and still is—much closer to them on a social and material level than the Western European metropolis. Historically speaking, the U.S. is the most successful former colony in the world and one of few examples of successful decolonization, even if it was only emancipation of one group of white people from their dependence on another group white people. Even during the period of unchallenged global American hegemony after the end of the Cold War, most parts of the inland United States resembled so-called third world countries when it came to the quality of public infrastructure or accessibility of quality public services like healthcare or education. The same can be asserted about the conditions in which the majority of the U.S. population are destined to live in today. The way the United States is policing its population seen from the other side of the Atlantic seems much closer to the practices of so-called “underdeveloped nations” than to the European standard: stumbling upon news from Watts or Fergusson, you could easily mistake the police for foreign occupying military forces on a remote Caribbean island. The recent storm of the right-wing mob on the Capitol did not conform to the noble image of the world’s oldest and leading parliamentary democracy but was rather reminiscent of what we know from the recent political history of Ukraine or Romania.

Both in Poland and in the U.S., the destruction of the trade unions has had a profound impact on political life, especially when it comes to the goals and narrative of the Left. The idea of a universally shared and inferior position that capital imposes on labor and thus the imperative to struggle for a world that would be less alienated both economically and socially was left behind and replaced with emancipation of the individual, bereft of class affiliation and therefore searching for identity. This emphasis on freedoms and liberties of the individual and the rejection of the limitations put on them by traditional values of the community meant that to be considered progressive, one had to denounce the many in the name of the one.

While the mainstream Left remained preoccupied with the particular, the problem of the common was captured by the Right and thus linked to regressive collective formations: nation, family, and religious affinity. The consequence is that nowadays the Right is the only one able to put the crisis of the commons and the communal on the table.30 Ironically, the New Left and its program of liberation of the individual from the shackles of tradition not only turned out to be impotent when it comes to opposing the reactionary populist revolt but proved its usefulness in another equally reactionary way: as an ally for the neoliberal notion of the subject as the consumer, rendering the idea of society as something more than the sum of its parts practically obsolete. How can there be an end to the frenetic search for identity when the very idea of community has been disassembled? The centrality of the notion of identity for the political project is a feature shared by the contemporary Right and Left; it is just a different identity that either side would like to see affirmed. In this sense, conservative populism is just white identity politics.

The identitarian turn was the Left’s adaptation to the failure of revolutionary politics. It happened at a different pace in the West and in the East, as the West witnessed it more or less two decades before the shock therapy of the early 1990s rocked the former Soviet Bloc, but the basic principle has remained the same: switching to symbolic issues as the only ones that can easily advance under the neoliberal hegemony as neoliberalism, in principle, does not have any problems with diversity and symbolic recognition. Of course, many neoliberals were rather neoconservatives with a lot of prejudices, but there has been no major structural obstacle to aligning the politics of recognition with neoliberal hegemony—unlike, for example, the insurmountable obstacles to redistributing material wealth under neoliberal regimes. A new form of white suprematism that emerged from this unfortunate concatenation is epitomized in the struggles around immigration that seem—again—identical in Poland and the U.S., and the same stands for the argumentative strategies of, for example, German AfD when it comes to immigrants. As a matter of fact, it was the latter that, playing on the East-West divide in Germany (that is, a divide of both material and cultural capital), expressed the core issue of populists’ mindset in a concise way: you (i.e., Western/liberal elites) want to integrate immigrants, while you have not been able to integrate us, although we are natural born citizens of this country, and while being oblivious when it comes to religious bigotry of the immigrants, you have nothing but disdain for our own traditional beliefs! It is a phenomenon that may be labelled as “skipping the line”: while we all queue for recognition, the petite-bourgeoisie and lower classes at the very end of the line believe that some others skip the line and steal their recognition—the migrants, ethnic minorities, women, homosexuals, etc.