I. Introduction1

In 1939, the Viennese economist and sociologist Otto Neurath (1882–1945) released Modern Man in the Making to an American public. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, Neurath’s pictorial statistical history of human technological adaptation and social cooperation addressed a modern audience searching for optimistic narratives amid an economically, politically, and socially volatile era.2 If not actual members of the managerial class, readers of Neurath’s book were immersed in a “culture of management” that permeated many aspects of modern life.3 The concerns of the broader public were addressed by managerial commitments to profitable business and social betterment through the promotion of efficiency during the interwar years. Between 1917 and 1939 Neurath frequently referenced Scientific Management and its program for promoting cooperation through efficiency.4 Abandoning theology and enlightenment liberalism, he even went so far as to propose an ethics modeled on an extrapolation of Scientific Management which would take the form of the extension of convention and habit into new forms of life.5 Thus Modern Man in the Making reflected the practical as well as ideological goals of managerial culture. Neurath rephrased these objectives in his concluding remarks: “men capable of judging themselves and their institutions scientifically should also be capable of widening the sphere of peaceful co-operation; … the more co-operative man is the more ‘modern’ he is.”6 Because Neurath was only rarely explicit in his advocacy for Scientific Management, the aim of this essay is to flesh out the underlying managerial goals implicit in Neurath’s proposal.

II. Visual Impact

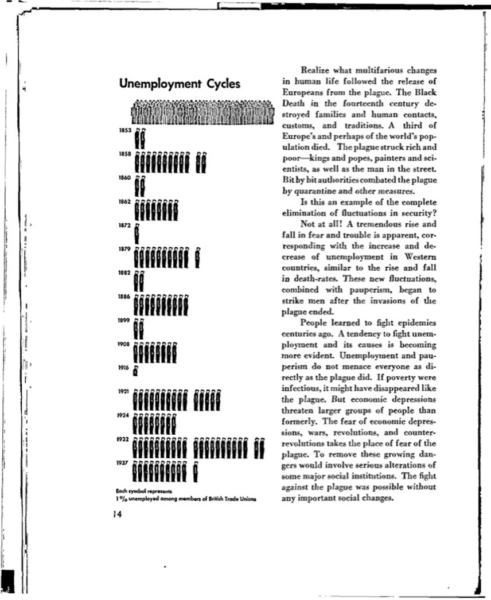

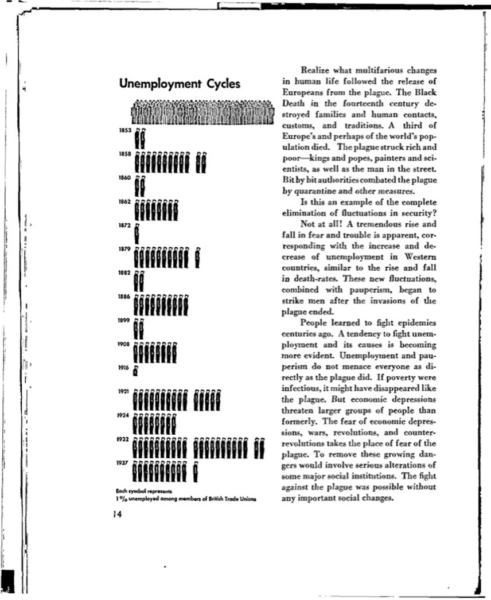

Visual impact was the key selling point of Modern Man in the Making. As reviewers remarked, the pictorial emphasis of Neurath’s book appealed to readers who were attracted to its easily scanned layouts. This was a quality based on the predominance of visually arresting, standardized statistical charts.7 Formally known as the Vienna Method, Neurath’s approach to visualizing statistical data, or ISOTYPE (International System of Typographic Picture Education), contributed to the book’s “reductive genius,” as one critic approvingly commented.8 Ostensibly, ISOTYPE increased a reader’s capacity to observe the progress of a widening scientific concept of the world. The typographic organization of Modern Man in the Making emphasized the one-thing-after-another continuity of information, as can be viewed in a progression of ISOTYPE charts and textual argumentation (fig. 1). Each ISOTYPE chart was constructed from “standardized elements which are put together like building blocks to convey ideas and coherent stories” (MMM 136). Gerd Arntz bore the responsibility for the general design of Modern Man in the Making. His extensive experience with modern and avant-garde publications no doubt informed his precise handling of layout to assemble “building blocks” of information.9

The typographic treatment of Neurath’s text and ISOTYPE charts facilitated the coordination of the twofold task of ISOTYPE: “to show social processes, and to bring all the facts of life into some recognisable relation to social processes.”10 The overall design of the book reinforced Neurath’s intention to achieve a “comprehensive” picture of modernity, and as he remarked in his forward, “Everybody, even one who is no scholar, is able to take a scientific attitude and to regard calmly the Pilgrimage of Man” (MMM 8). Along the way, readers of Modern Man in the Making observed statistical comparisons of periodic changes in trade, war, colonialism, slavery, illness, population, ecologies, migration, leisure, suicide, manufacturing, and poverty (to name just a few areas of data collection and visualization represented in the book).

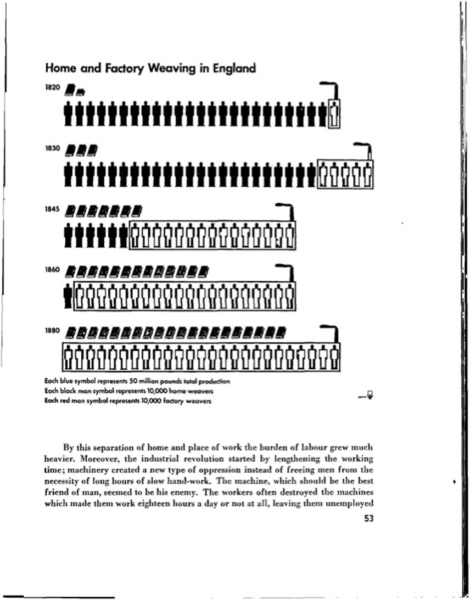

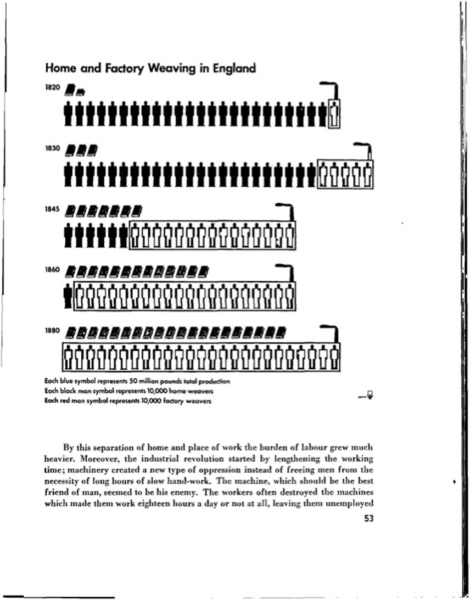

A typical example of Neurath and his team’s approach to the composition of an ISOTYPE chart is best observed in “Home and Factory Weaving in England” (fig. 2) (MMM 53). The chart depicts a statistical comparison of production, home weaving, and factory weaving between the years 1820 and 1880. It shows a massive increase of textile production tied to the increase of factory labor. By 1880 all weaving was done in a factory. A reader of Modern Man in the Making could scan the statistical representation of a shift from home weaving to factory weaving, and the subsequent increase in textile production along the five vertically stacked horizontal lines of pictographs. Speaking in general terms on the creation of a standard ISOTYPE figure, Neurath’s advised: “Above all pictorial signs must be created that can be ‘read,’ just as we can read letters.”11 And, drawing on the history of the mechanical reproduction of alphabetic signs, Neurath linked ISOTYPE to a tradition of typographic design: “A further essential element of ISOTYPE symbols is that they should be suitable for assembling together like the characters of a written or printed line.”12 With very rare exception, Neurath and his team designed ISOTYPE charts like “Home and Factory Weaving in England” to follow a temporal sequencing that was in keeping with alphabetic and line sequencing of traditional western page layout. The time-axis of the ISOTYPE chart, moving downward from upper left (at 1820) to lower left (at 1880), visually connects to text block just below. The adherence to historical standards of design and conventions of reading becomes clear where its text expands the pictured concept: “By this separation of home and place of work the burden of labor grew much heavier” (MMM 53). Neurath intended the information packed into the ISOTYPE chart above to align with the textual representation of historical facts below, thereby extending Neurath’s earlier observation on the impact of mechanization on weaving: “The growing western mechanization changed the whole of life, especially the worker’s life” (MMM 52).13

In general, Neurath’s ISOTYPE was designed to guide viewers, possessing varying degrees of literacy, toward understanding their socio-economic circumstances. From specialists to laypersons, ISOTYPE charts were intended to communicate statistical information to the widest audience possible. As for a more targeted audience, the clarity of his ISOTYPE method appealed to a rising managerial class who were already conversant with methods of pictorial statistical communication. Neurath had introduced his ISOTYPE method to an American audience on the cover of the March 1932 issue of Survey Graphic, and beginning in 1934 his associate Rudolf Modley, working under the aegis of Pictorial Statistics Inc., had designed charts for a variety of institutions including the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, the Works Progress Administration, and the Rural Electrification Administration.14 By 1937 ISOTYPE was so prevalent in institutional, bureaucratic, and administrative contexts that H.G. Funkhouser included a “special bibliography on the Vienna method” to his 1937 article “Historical Development of the Graphical Representation of Statistical Data.”15 In 1939, when Neurath published Modern Man in the Making, ISOTYPE and pictorial statistics were ubiquitous in New Deal administrative and affiliate forms of communication directed at administrators and agents (but rarely to the general public).16 And pictographic charts similar to ISOTYPE could be found in advertisements and articles published in Fortune magazine.

III. Scientific Management

The so called “managerial revolution”—a term made famous by James Burnham in 1941 and which had long since gained a cultural foothold when Neurath published his book Modern Man in the Making—was used to identify the rise of a bureaucratic and technocratic ruling class.17 Critics of a managerial revolution like Burnham argued that a socially engineered utopia would develop from factory to city, to nation, to finally encompass the globe, which would then be divided between three managerially controlled centers—Europe, Asia, and the United States.18 Burnham’s book was, in part, a response to decades-long enthusiasm for Scientific Management and the application of a set of principles originally formulated by Frederick Taylor to efficiently organize labor. Burnham’s analysis of the rise of a managerial class and the resulting creation of massive bureaucratic systems of control in Germany, Soviet Union, and the United States did not mention Neurath, Modern Man in the Making, or the use of ISOTYPE to visualize data relevant to the managerial enterprise. Nevertheless, there was a direct connection between ISOTYPE and Scientific Management in that the management expert Mary Flédderus financed the International Foundation for Visual Education, which was responsible for the design of Modern Man in the Making. And, as already mentioned above, the use of ISOTYPE and its American counterpart Pictorial Statistics across a range of administrative printed materials—pamphlets, posters, magazines, advertisements, educational displays, etc.—in the era of New Deal reform in the United States indicates that it was a preferred mode of bureaucratic communication compatible with Burnham’s analysis.

There exists a very large and still growing scholarly literature on Neurath and his ISOTYPE method.19 Within this body of research several scholarly articles are noteworthy for their reckoning with Neurath’s engagement with managerial trends in the early twentieth century, but they remain underdeveloped.20 It is unclear whether or not Neurath was committed to overturning Taylorism and its legacy as Scientific Management. Neurath’s references to Scientific Management implied integration rather than rejection. And this appears more likely when considering the possibility that Neurath was less than enthusiastic about achieving social-democratic goals, as John Gunnell argues, “from the bottom up than by social planning from the top down.”21 Certainly, as Andrew Shanken indicates, Neurath’s ISOTYPE was an expression of a managerial mind devoted to the technical problems of order and as an expanding method of managerial support in the form of applied diagrams—or instructions—for bureaucratic control. While Neurath did not anticipate Burnham’s predictions, he did register the potential for large-scale administrative control in Modern Man in the Making. Sensing this, one reviewer of the book commented on Neurath’s having “seen the shadow of coming events when he wrote, probably many weeks ago, ‘No alliance is impossible.’” Such an alliance between managers and the state apparatus under the command of “Herr Hitler,” as the reviewer goes on to argue, was hostile to Neurath’s sense of “peaceful cooperation.”22 And yet, it was unclear if Neurath’s prescriptions did not encourage the global expansion of bureaucratic order—peaceful or otherwise.

There exists some evidence that Neurath was immersed in managerial discourses as received and interpreted in the German-speaking world of the early twentieth century. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Scientific Management had encouraged fervent emulation in Europe. The American system of Scientific Management provided a template for advancing technocratic expertise in the analysis of tasks proportional to wages. Less concerned with its technical features, European followers of Taylor from across the political spectrum embraced Scientific Management because of its social and political applications as they related to large scale organization.23 Suggesting something of Neurath’s ambivalence on the topic, Charles Maier posits, “Ostensibly Taylor’s factory could become the nucleic building bock of a post-bourgeois world, or at least a secure managerial one.”24 Taylor and his followers (both in the U.S. and in Europe) were committed to addressing the problems of disorder, and the machine shop provided a case study that would supply solutions for boarder social problems.25 Neurath first encountered Taylorism while directing the Museum of War Economy in Leipzig and while working at the Munich Central Planning Office. In both locations, he would have directly experienced the transfer of Scientific Management to Germany. Mostly academics, German advocates for Taylor’s system promoted both efficiency and cooperation between labor and management, despite known labor tensions that arose in the United States (MAI 179). By the end of World War I “bad” Taylorism (exploitive labor policies and mechanization of work) gave way to “good” Taylorism (Qualität and efficient labor).26

Neurath was cognizant of the deleterious effects of Scientific Management on labor, in keeping with criticisms of “bad” Taylorism. Like academics critical of the movement’s adversarial position to labor in Germany, he was inclined to adapt “good” Taylorism to social issues.27 In “The Converse Taylor System” (1917), Neurath acknowledged the fear that Scientific Management, even where its introduction was to the advantage of workers, could too easily “increase the general mechanization of living” (CTS 130). In his early consideration of the manager’s cost-benefit equations, Neurath was less inclined to assume that the impulse to institute greater managerial oversight merely arose from an “imperious demand,” as Sigfried Giedion later surmised.28 Indeed, in his evaluation of the Taylor system, Neurath proposed an expansion of the principles of Scientific Management to incorporate its effects in “the conscious shaping of life to the whole body politic” (CTS 131). From his perspective, this would include a more extensive approach to labor as an administrative economy aimed for “a fuller use of capacity while trying to abolish the underemployment or non-employment of abilities” (CTS 132). As early as 1915, Horace Drurey had observed that Scientific Management had de-emphasized time-motion study and efficiency in order to devote more energy to the encouragement of “mental change.” The result would be that groups could achieve agreed upon goals through “friendly cöoperation.”29 Importantly, for Neurath, the implications of Taylorism or “technism,” like those of technology as a whole, were not one-sidedly tied to any one system of application (CTS 131). His project was not one that inverted Taylorism, as the title of the early essay suggested. In keeping with a managerial point of view, Neurath later remarked, “To socialize an economy means to lead it toward a planned administration for and by society.”30 In a planned administration, it was the managerial class—largely composed of social engineers and those with a scientific conception of the world—who were tasked with the “conscious shaping of life.”31 Despite the fact that Taylor’s idealistic goals of increasing worker income and providing greater amounts of leisure time were easily discarded, Neurath incorporated the underlying belief that knowledge, efficiency, and administrative planning could effect positive social reform.

For Neurath, progressive or positive social change was an ideal outcome of increased cooperation. In the literature on Scientific Management, cooperation resulted in an optimized working system that, according to its principles, better distributed surplus earnings. Theoretically, cooperation between management and labor would thrive with the implementation of “differential rate,” a calculation to determine premium pay relative to efficient production. Surplus profit derived from increased efficiency would be mutually beneficial to both management and labor.32 Neurath’s specific references to cooperation in Modern Man in the Making, as it related to the orthodoxies of Scientific Management, scientific studies, and technological advances such as time-motion analysis posited continual forms of cooperation to achieve mutually agreed upon goals, as in his example of post-WWI reconstruction in France and Belgium (MMM 106). Scientifically transformed social institutions, according to Neurath, should produce a greater “sense of social security that is now lacking” (MMM 132)

IV. “Collectivization” of Life

Modern Man in the Making’s furtherance of rationalized social reform would have resonated with an American audience, especially those who had experienced the impact of Scientific Management on New Deal policy making throughout the 1930s. Whether the efforts of managerial minded social reformers were successful or not, Scientific Management offered tools for economic recovery and social cohesion along the lines Neurath mentioned in Modern Man in the Making (MAI 260–62).

That same audience had to contend with radical changes to everyday life—especially work, leisure, home, and family life—as it was being reconfigured by modernity. In Modern Man in the Making, Neurath drew a correspondence between the social concept of “‘only child’ [as] an urgent modern problem” in the Netherlands and the rise of kindergartens, playgrounds, and other social institutions (MMM 113–14). In “Man’s Daily Life,” the final section of his book, the text enumerated data collected from statistical atlases and yearbooks. Neurath touched on the growing population of working mothers, industrialization, women’s suffrage, labor and leisure time, sporting event attendance, militarization of public and private life, travel, prolongation of life, household technologies, and falling church attendance. He asked, “What do all these trends towards modernity mean in man’s daily life” (MMM 113)? Appearing at strategic intervals throughout the layout of the book, ISOTYPE charts vividly presented a range of statistical facts that seemed to answer that question. The combination of statistical charts provided readers with a schematic map with multiple views—or visualizations—of socially organized human life.33 His account provided readers with insight into the waning of a premodern oikos, or the shift from a social emphasis on family and home to a modern economic emphasis on population overseen by a managerial class.

The problem of the “only child” prompted Neurath to speculate on the role that managerialism might play in the social organization of a child’s life. “The ‘only child’ does not easily learn within the family how to adapt itself to its environment. Hence kindergartens are necessary not only for modern pedagogy in general, but also for mental hygiene” (MMM 114). Traditionally, large families took on the role of early education. But, as Neurath observed, a decrease in birth-rates obsolesced familial “collective educational groups” (MMM 114). In addition to other significant factors, namely two working parents, there was an increase in the “support all kinds of children’s communities,” such as kindergartens, playgrounds, and alternative institutions intended for children (MMM 114). Therefore, family elders who previously were responsible for guiding children in strategies of environmental adaptation were replaced by experts in childcare. He concluded, “This collectivization of the life of children is connected not only with the trend in the birth-rate but also with other changes” (MMM 114). By “other changes” Neurath meant to indicate a general trend toward secularization in the West.

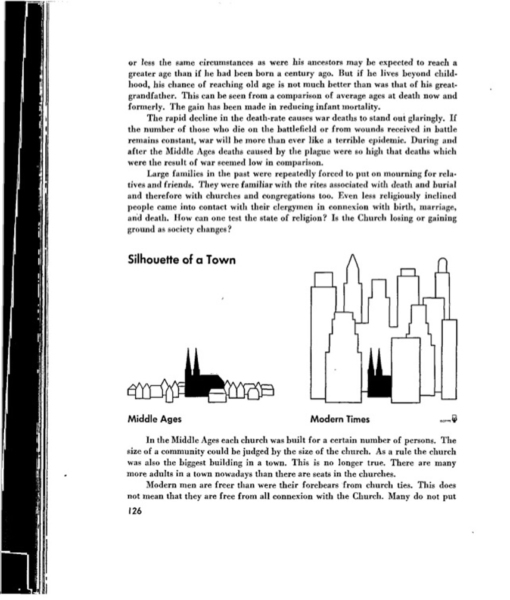

Children collectivized under the organizational oversight of experts in childcare was, according to Neurath’s social-physical calculations of the impact of modernization, correlated to the decline of religious observance. In the concluding passages of “Man’s Daily Life,” a series of charts compared population rates with the increasing decentralized role of the church in contemporary life. Using all of this data and more, Neurath presented his fundamental point: dwindling birthrates correlated to the waning influence of religion in the modern world. Neurath and his team visualized this transition—what he referred to as a liberation from “church ties”—with a pictographic comparison of a town in the “Middle Ages” and a city in “Modern Times” (fig. 3) (MMM 126). The comparative depiction of both eras features a silhouette of a cathedral, with the latter dominating the buildings that are arrayed around it and the latter dwarfed by surrounding skyscrapers. Neurath’s visual comparison implied that where there was a loss of theological authority there was a simultaneous gain in what he referred to elsewhere as a “scientific world-conception.”34

In the bibliographic appendix of Modern Man in the Making, Neurath appended a reference to the American journalist Walter Lippmann’s A Preface to Morals (1929) to “Silhouette of a Town.” There he quoted Lippmann’s observation: “[Modern man] must be guided by his conscience. But when he searches his conscience, he finds no fixed point outside of it by which he can take his bearings. He does not really believe that there is such a point, because he himself has moved about too fast to fix any point long enough in his mind” (MMM 157).35 Lippmann’s book diagnosed the anxiety of an American public facing the panic raising dissolution of “certainty itself” (APM 19). To the extent that “modern man” had lost “his bearings,” he claimed that this dissipation of a center was due to the waning influence of traditional authority (APM 59). Both Lippmann and Neurath were skeptical of fixed belief. Lippmann veered closest to Neurath’s anti-foundationalist philosophy—a Whiggish concept of perpetual epistemic renewal—where he advocated for a rational morality akin to self-discipline.36 Like Neurath, Lippmann believed it a gain for human progress to be released from the dogmas of theology. And, like Lippmann, Neurath too ventured to propose principles that lent coherence and direction for modern living. Both writers agreed that a scientifically educated managerial class was best situated to school a public in rational morality commensurate with a modern social sphere.

Neurath’s account of modern progress—namely the demise of theological thought in the West—was consistent with his program to ban metaphysics from philosophy, sociology, and economics. Neurath’s “world conception” provided the groundwork for his establishment of a physicalist approach to all three fields. For Neurath, a physicalist approach refuted the idealistic-metaphysical current of his era—more commonly known as Geisteswissenschaften—a science of spirit. The physicalist thing-language of his statistically grounded sociology was meant as a deflationary tactic aimed at Geisteswissenschaften, an approach that Neurath hoped would overcome a pointless a priori metaphysics (SWC 45). For Neurath, the natural sciences provided the appropriate starting point for his ongoing production of a unified world conception, a concept that would eradicate the misguided profundities of “spirit” and other fallacious abstractions. He preferred more “empirically meaningful concepts as offer, demand, export and import, warfare, emigration, etc.” (SWC 44). His was an approach “without a world-view” that endeavored to confront “‘world-views’ of all kinds.”37 Importantly, Neurath’s anti-metaphysics entailed the rejection of a lingering “residue of theology”—what he took to be a habit that filled a gap between an ostensible invisible structure and a concrete experience.38

In response to the decrease of theologically inspired Geisteswissenschaften and an increase of a general “technical organization” of all things, Neurath invoked Scientific Management as presenting a guiding principle. On this point, Neurath wrote:

Ethics, which dealt formerly either with the laws of God or at least with laws “an sich,” in other words, laws from which in a certain sense God had been eliminated, is now supplanted by inquiries which make it possible for man to attain happiness by definite arrangements or definite methods of conduct (behavior). Instead of the priest we find the physiological and the sociological organizer. (PVC 50)

Neurath’s use of the term “an sich” was a thinly veiled reference to Kantian enlightenment liberalism in his account of what was displaced by “the physiological and the sociological organizer.”39 This newly installed organizer—or manager—followed the natural sciences. Organization and its oversight were not to be based on what one ought to do but based on an empirical account of what is. As he went on assert, “No science can teach what ‘should be done;’ it can assert only that because A and B have happened, a very definite C follows” (PVC 50). Neurath compared the ethical-causal equation to a machine “tested to measure its lifting effect” (PVC 50). Such an approach involved “engineering, gymnastics (hygiene) and the social technology of today, all of which have an influence on scientific management and commercial organization and thus on human life as a whole” (PVC 50).40 This view was commensurate with the influence of Marx and Engels and their materialist conception of history on Neurath’s physicalism and his scientific world-conception.41 Neurath took their concept of history—the abolishment of the past based on a grouping of contemporary propositions—“as a strictly scientific way of looking at things” that posits “testable assertions.”42

V. Conclusion: Managerial Mind

Managerialism had yet to win the day in 1939. Was this a testable assertion in the form of ISOTYPE? If it was the case that the decline of church attendance resulted in the rise of a new clerisy in the form of a managerial class that increasingly attended to all aspects of social organization including the “collectivization of the life of children,” then it was likely that kindergartens, playgrounds, and other childcare institutions were symbols of modernity. In 1937, Neurath and his team had designed a cartogram of a fictional modern city, in order to demonstrate the ISOTYPE method applied to urban planning (fig. 4). The cartogram was featured in his article, “Visual Representation of Architectural Problems,” which appeared in Architectural Record.43 The cartogram featured factories, kindergartens, playgrounds, and other urban structures (but, significantly, no churches). The cartogram charted the expansion of managerialism in keeping with what could be referred to as the Taylorized city. Neurath and his team could have designed a similar cartogram for a city in the United States to include in Modern Man in the Making, perhaps drawing on data that was used for the cartogram of New York City included in Gesellschaft und Wirtschaft atlas from 1930 (fig. 5). If this had been the case, Modern Man in the Making would have supplied readers with the transcendent view of the social engineer. Readers could have tested Neurath’s cartographic assertion in the form of an ISOTYPE against their experiences in urban spaces across America.44 The addition of a cartogram, however, would not solve the problem of Neurath’s conflation of correlation and causality. There simply were too many data points and too little context to have drawn a firm conclusion.45 Instead, Neurath opted to conclude his book with a caution and an ISOTYPE of a skyscraper (fig. 6).

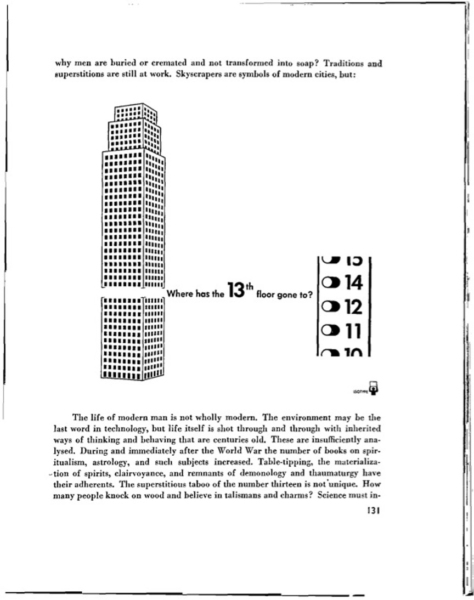

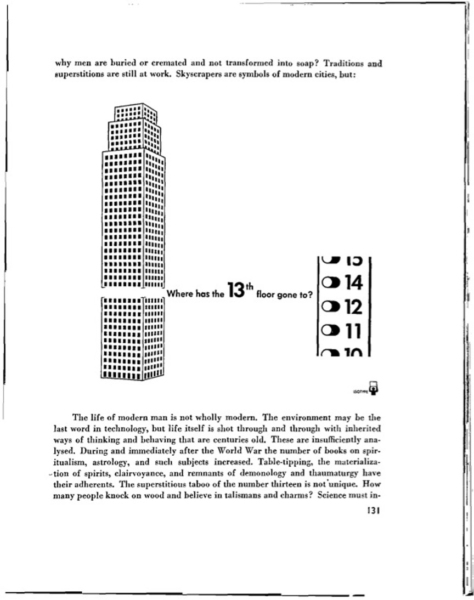

“Skyscrapers are symbols of modern cities, but:” an ISOTYPE of a skyscraper followed, with the colon indicating that the image was meant to be read as a continuation of the text. The skyscraper displays two tiers at its top, and a cut-away shows a missing floor near the lower portion of the building with text that reads: “Where has the 13th floor gone to?” To the right of the text there is a graphic/typographic representation of a section of an elevator control panel. As an example of physicalist thing-language of ISOTYPE, the image was itself an articulation of content that completed Neurath’s thought. What was striking about Neurath’s inclusion of this ISOTYPE was that it stood as an icon of socio-technological achievement and symbolized the fulfillment of managerialism. At the same time, it represented the postponement of the ultimate achievement of managerial rationality in the form of a superstition. In this sense, the image of the skyscraper with its absent thirteenth floor was a reminder to those readers who occupied tall buildings that “modern man” was still in the “making.” Just below the image a new paragraph began: “The life of modern man is not wholly modern. The environment may be the last word in technology, but life itself is shot through and through with inherited ways of thinking and behaving that are centuries old. These are insufficiently analysed” (MMM 131).

Neurath’s ISOTYPE skyscraper accomplished two goals. First, in order to solidify the relevance of the book to a managerial audience, Neurath concluded Modern Man in the Making with an icon of managerial ascent in the United States. The image of the skyscraper was a sure-fire attention grabber because it was consistent with an existing popular cultural imaginary.46 The image of the skyscraper had caught the attention of the American public across a range of media: from displaying feats of technological progress such as Lewis Hine’s photo-essay, “Up From the Streets,” in The Survey (1931) and a photograph of construction workers having lunch high above Manhattan published in The Herald Tribune (1932); to featuring tall buildings in popular films like Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last (1923) and Feet First (1930) and Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy’s Liberty (1929); to John Dos Passos’s novel Manhattan Transfer (1925), to name just a few examples. It was the case that the skyscraper figured into what Roland Marchand has identified as a pictorial formula in American advertising established in the 1920s and that persisted throughout the 1930s. These advertising images, according to Marchand, symbolized the status and authority of the rising managerial class, whose members occupied the well-appointed offices towering over urban spaces.47 By the late 1930s, when Knopf published Modern Man in the Making, urban American readers could turn away from the book in their hands and survey a skyline that expressed managerial concentration in the form of vertically rising corporate offices.48

If read with the above in mind, Modern Man in the Making was an historical account of the concentration of managerial control. “But: …” the corrosive “acids of modernity,” as Lippmann put it, left a remainder from the past (APM 61–63). Cognizance of this remainder posited Neurath’s second goal. The image of the skyscraper signified the deferral of the triumph of managerial rationality in the form of a superstition. To enter a lobby of any number of tall buildings in New York City in the late 1930s would be to confront customs that were both contemporary and archaic.49 A lingering habit of mind was embedded within an icon of technological expertise and managerial control. As Neurath remarked some years earlier, “It is easy to see that our life is full of habits which have no technical basis, which spring only from tradition. … Usually, we grasp the possibility of detaching habits only when we have overcome them.”50 Neurath intended the concluding image of Modern Man in the Making to highlight a detachable habit in the form of a prohibition against the use of the number “13.”

He went on to observe that residual habits and traditions without technical basis persisted into the modern era. And, in the case of the managerial class who occupied the tall buildings of Manhattan, adherents to modern forms of life carried on their avoidance of a “superstitious taboo,” which had its “roots in ancient beliefs” (MMM 131–32). Neurath directed his caution to managers who, in following the up-to-date managerial sciences, may have neglected to reflect on still active ancient beliefs. As Neurath advised, “[N]o scientist can avoid the influence of tradition when he begins his investigations” (MMM 132). Neurath’s appeal to the “scientist” echoed already existing literature and forms of instruction within business management programs. While Drurey had observed that Scientific Management had encouraged “mental change” in laborers (as mentioned above), managers themselves had yet to interrogate the signs and symptoms of their own mental outlook. As Neurath advised, release from the encumbrances of the residue of past beliefs required that a scientifically informed manager rigorously follow a step-by-step transformation of the self. The manager as a modern man in the making was to be, therefore, on the alert for unconsciously held beliefs, which he must endeavor to eradicate in the interest of achieving the goal of suppressing non-technically relevant habits.

As a diagnostic tool, Neurath’s skyscraper ISOTYPE and its use to historicize managerialism revealed that while the managerial class had been emancipated from the orthodoxies of theology and from enlightenment liberalism, they were still subject to the lingering dictates of traditions in forms of magical thinking and superstition.51 In other words, despite the gains made by the managerial revolution, there had yet to be a complete break with the covenantal bonds with the past.

The interpretation of Modern Man in the Making that I propose takes the skyscraper as having obsolesced the cathedral as a beacon of authority. In the wake of an acknowledgement of theological outmodedness and of the limits of enlightenment liberalism—both instances of metaphysics, according to Neurath—the principles of Scientific Management superseded dogma and moral and ethical guidance. As discussed above, it was the managerial class populated by social engineers and those administrators who possessed a scientific conception of the world who took on the responsibility of a “conscious shaping of life,” as Neurath put it.53 The new clerisy was to dedicate itself to a therapeutic process of identifying and eliminating metaphysically grounded habits. In Neurath’s case, this came in the form of his advice to readers of Modern Man in the Making. They should remain vigilant so as not to unconsciously reproduce customs inherited from the past. Guided by the “physiological and the sociological organizer,” progress made in the project of making modern man, therefore, was measured in stages of coming to self-consciousness. The secular ritual of constant self-evaluation and perpetual self-revelation was, no doubt, performed in the offices of personnel departments within corporations, where experts practiced therapies of managerial administration on management.

Notes

I. Introduction1

In 1939, the Viennese economist and sociologist Otto Neurath (1882–1945) released Modern Man in the Making to an American public. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, Neurath’s pictorial statistical history of human technological adaptation and social cooperation addressed a modern audience searching for optimistic narratives amid an economically, politically, and socially volatile era.2 If not actual members of the managerial class, readers of Neurath’s book were immersed in a “culture of management” that permeated many aspects of modern life.3 The concerns of the broader public were addressed by managerial commitments to profitable business and social betterment through the promotion of efficiency during the interwar years. Between 1917 and 1939 Neurath frequently referenced Scientific Management and its program for promoting cooperation through efficiency.4 Abandoning theology and enlightenment liberalism, he even went so far as to propose an ethics modeled on an extrapolation of Scientific Management which would take the form of the extension of convention and habit into new forms of life.5 Thus Modern Man in the Making reflected the practical as well as ideological goals of managerial culture. Neurath rephrased these objectives in his concluding remarks: “men capable of judging themselves and their institutions scientifically should also be capable of widening the sphere of peaceful co-operation; … the more co-operative man is the more ‘modern’ he is.”6 Because Neurath was only rarely explicit in his advocacy for Scientific Management, the aim of this essay is to flesh out the underlying managerial goals implicit in Neurath’s proposal.

II. Visual Impact

Visual impact was the key selling point of Modern Man in the Making. As reviewers remarked, the pictorial emphasis of Neurath’s book appealed to readers who were attracted to its easily scanned layouts. This was a quality based on the predominance of visually arresting, standardized statistical charts.7 Formally known as the Vienna Method, Neurath’s approach to visualizing statistical data, or ISOTYPE (International System of Typographic Picture Education), contributed to the book’s “reductive genius,” as one critic approvingly commented.8 Ostensibly, ISOTYPE increased a reader’s capacity to observe the progress of a widening scientific concept of the world. The typographic organization of Modern Man in the Making emphasized the one-thing-after-another continuity of information, as can be viewed in a progression of ISOTYPE charts and textual argumentation (fig. 1). Each ISOTYPE chart was constructed from “standardized elements which are put together like building blocks to convey ideas and coherent stories” (MMM 136). Gerd Arntz bore the responsibility for the general design of Modern Man in the Making. His extensive experience with modern and avant-garde publications no doubt informed his precise handling of layout to assemble “building blocks” of information.9

The typographic treatment of Neurath’s text and ISOTYPE charts facilitated the coordination of the twofold task of ISOTYPE: “to show social processes, and to bring all the facts of life into some recognisable relation to social processes.”10 The overall design of the book reinforced Neurath’s intention to achieve a “comprehensive” picture of modernity, and as he remarked in his forward, “Everybody, even one who is no scholar, is able to take a scientific attitude and to regard calmly the Pilgrimage of Man” (MMM 8). Along the way, readers of Modern Man in the Making observed statistical comparisons of periodic changes in trade, war, colonialism, slavery, illness, population, ecologies, migration, leisure, suicide, manufacturing, and poverty (to name just a few areas of data collection and visualization represented in the book).

A typical example of Neurath and his team’s approach to the composition of an ISOTYPE chart is best observed in “Home and Factory Weaving in England” (fig. 2) (MMM 53). The chart depicts a statistical comparison of production, home weaving, and factory weaving between the years 1820 and 1880. It shows a massive increase of textile production tied to the increase of factory labor. By 1880 all weaving was done in a factory. A reader of Modern Man in the Making could scan the statistical representation of a shift from home weaving to factory weaving, and the subsequent increase in textile production along the five vertically stacked horizontal lines of pictographs. Speaking in general terms on the creation of a standard ISOTYPE figure, Neurath’s advised: “Above all pictorial signs must be created that can be ‘read,’ just as we can read letters.”11 And, drawing on the history of the mechanical reproduction of alphabetic signs, Neurath linked ISOTYPE to a tradition of typographic design: “A further essential element of ISOTYPE symbols is that they should be suitable for assembling together like the characters of a written or printed line.”12 With very rare exception, Neurath and his team designed ISOTYPE charts like “Home and Factory Weaving in England” to follow a temporal sequencing that was in keeping with alphabetic and line sequencing of traditional western page layout. The time-axis of the ISOTYPE chart, moving downward from upper left (at 1820) to lower left (at 1880), visually connects to text block just below. The adherence to historical standards of design and conventions of reading becomes clear where its text expands the pictured concept: “By this separation of home and place of work the burden of labor grew much heavier” (MMM 53). Neurath intended the information packed into the ISOTYPE chart above to align with the textual representation of historical facts below, thereby extending Neurath’s earlier observation on the impact of mechanization on weaving: “The growing western mechanization changed the whole of life, especially the worker’s life” (MMM 52).13

In general, Neurath’s ISOTYPE was designed to guide viewers, possessing varying degrees of literacy, toward understanding their socio-economic circumstances. From specialists to laypersons, ISOTYPE charts were intended to communicate statistical information to the widest audience possible. As for a more targeted audience, the clarity of his ISOTYPE method appealed to a rising managerial class who were already conversant with methods of pictorial statistical communication. Neurath had introduced his ISOTYPE method to an American audience on the cover of the March 1932 issue of Survey Graphic, and beginning in 1934 his associate Rudolf Modley, working under the aegis of Pictorial Statistics Inc., had designed charts for a variety of institutions including the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, the Works Progress Administration, and the Rural Electrification Administration.14 By 1937 ISOTYPE was so prevalent in institutional, bureaucratic, and administrative contexts that H.G. Funkhouser included a “special bibliography on the Vienna method” to his 1937 article “Historical Development of the Graphical Representation of Statistical Data.”15 In 1939, when Neurath published Modern Man in the Making, ISOTYPE and pictorial statistics were ubiquitous in New Deal administrative and affiliate forms of communication directed at administrators and agents (but rarely to the general public).16 And pictographic charts similar to ISOTYPE could be found in advertisements and articles published in Fortune magazine.

III. Scientific Management

The so called “managerial revolution”—a term made famous by James Burnham in 1941 and which had long since gained a cultural foothold when Neurath published his book Modern Man in the Making—was used to identify the rise of a bureaucratic and technocratic ruling class.17 Critics of a managerial revolution like Burnham argued that a socially engineered utopia would develop from factory to city, to nation, to finally encompass the globe, which would then be divided between three managerially controlled centers—Europe, Asia, and the United States.18 Burnham’s book was, in part, a response to decades-long enthusiasm for Scientific Management and the application of a set of principles originally formulated by Frederick Taylor to efficiently organize labor. Burnham’s analysis of the rise of a managerial class and the resulting creation of massive bureaucratic systems of control in Germany, Soviet Union, and the United States did not mention Neurath, Modern Man in the Making, or the use of ISOTYPE to visualize data relevant to the managerial enterprise. Nevertheless, there was a direct connection between ISOTYPE and Scientific Management in that the management expert Mary Flédderus financed the International Foundation for Visual Education, which was responsible for the design of Modern Man in the Making. And, as already mentioned above, the use of ISOTYPE and its American counterpart Pictorial Statistics across a range of administrative printed materials—pamphlets, posters, magazines, advertisements, educational displays, etc.—in the era of New Deal reform in the United States indicates that it was a preferred mode of bureaucratic communication compatible with Burnham’s analysis.

There exists a very large and still growing scholarly literature on Neurath and his ISOTYPE method.19 Within this body of research several scholarly articles are noteworthy for their reckoning with Neurath’s engagement with managerial trends in the early twentieth century, but they remain underdeveloped.20 It is unclear whether or not Neurath was committed to overturning Taylorism and its legacy as Scientific Management. Neurath’s references to Scientific Management implied integration rather than rejection. And this appears more likely when considering the possibility that Neurath was less than enthusiastic about achieving social-democratic goals, as John Gunnell argues, “from the bottom up than by social planning from the top down.”21 Certainly, as Andrew Shanken indicates, Neurath’s ISOTYPE was an expression of a managerial mind devoted to the technical problems of order and as an expanding method of managerial support in the form of applied diagrams—or instructions—for bureaucratic control. While Neurath did not anticipate Burnham’s predictions, he did register the potential for large-scale administrative control in Modern Man in the Making. Sensing this, one reviewer of the book commented on Neurath’s having “seen the shadow of coming events when he wrote, probably many weeks ago, ‘No alliance is impossible.’” Such an alliance between managers and the state apparatus under the command of “Herr Hitler,” as the reviewer goes on to argue, was hostile to Neurath’s sense of “peaceful cooperation.”22 And yet, it was unclear if Neurath’s prescriptions did not encourage the global expansion of bureaucratic order—peaceful or otherwise.

There exists some evidence that Neurath was immersed in managerial discourses as received and interpreted in the German-speaking world of the early twentieth century. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Scientific Management had encouraged fervent emulation in Europe. The American system of Scientific Management provided a template for advancing technocratic expertise in the analysis of tasks proportional to wages. Less concerned with its technical features, European followers of Taylor from across the political spectrum embraced Scientific Management because of its social and political applications as they related to large scale organization.23 Suggesting something of Neurath’s ambivalence on the topic, Charles Maier posits, “Ostensibly Taylor’s factory could become the nucleic building bock of a post-bourgeois world, or at least a secure managerial one.”24 Taylor and his followers (both in the U.S. and in Europe) were committed to addressing the problems of disorder, and the machine shop provided a case study that would supply solutions for boarder social problems.25 Neurath first encountered Taylorism while directing the Museum of War Economy in Leipzig and while working at the Munich Central Planning Office. In both locations, he would have directly experienced the transfer of Scientific Management to Germany. Mostly academics, German advocates for Taylor’s system promoted both efficiency and cooperation between labor and management, despite known labor tensions that arose in the United States (MAI 179). By the end of World War I “bad” Taylorism (exploitive labor policies and mechanization of work) gave way to “good” Taylorism (Qualität and efficient labor).26

Neurath was cognizant of the deleterious effects of Scientific Management on labor, in keeping with criticisms of “bad” Taylorism. Like academics critical of the movement’s adversarial position to labor in Germany, he was inclined to adapt “good” Taylorism to social issues.27 In “The Converse Taylor System” (1917), Neurath acknowledged the fear that Scientific Management, even where its introduction was to the advantage of workers, could too easily “increase the general mechanization of living” (CTS 130). In his early consideration of the manager’s cost-benefit equations, Neurath was less inclined to assume that the impulse to institute greater managerial oversight merely arose from an “imperious demand,” as Sigfried Giedion later surmised.28 Indeed, in his evaluation of the Taylor system, Neurath proposed an expansion of the principles of Scientific Management to incorporate its effects in “the conscious shaping of life to the whole body politic” (CTS 131). From his perspective, this would include a more extensive approach to labor as an administrative economy aimed for “a fuller use of capacity while trying to abolish the underemployment or non-employment of abilities” (CTS 132). As early as 1915, Horace Drurey had observed that Scientific Management had de-emphasized time-motion study and efficiency in order to devote more energy to the encouragement of “mental change.” The result would be that groups could achieve agreed upon goals through “friendly cöoperation.”29 Importantly, for Neurath, the implications of Taylorism or “technism,” like those of technology as a whole, were not one-sidedly tied to any one system of application (CTS 131). His project was not one that inverted Taylorism, as the title of the early essay suggested. In keeping with a managerial point of view, Neurath later remarked, “To socialize an economy means to lead it toward a planned administration for and by society.”30 In a planned administration, it was the managerial class—largely composed of social engineers and those with a scientific conception of the world—who were tasked with the “conscious shaping of life.”31 Despite the fact that Taylor’s idealistic goals of increasing worker income and providing greater amounts of leisure time were easily discarded, Neurath incorporated the underlying belief that knowledge, efficiency, and administrative planning could effect positive social reform.

For Neurath, progressive or positive social change was an ideal outcome of increased cooperation. In the literature on Scientific Management, cooperation resulted in an optimized working system that, according to its principles, better distributed surplus earnings. Theoretically, cooperation between management and labor would thrive with the implementation of “differential rate,” a calculation to determine premium pay relative to efficient production. Surplus profit derived from increased efficiency would be mutually beneficial to both management and labor.32 Neurath’s specific references to cooperation in Modern Man in the Making, as it related to the orthodoxies of Scientific Management, scientific studies, and technological advances such as time-motion analysis posited continual forms of cooperation to achieve mutually agreed upon goals, as in his example of post-WWI reconstruction in France and Belgium (MMM 106). Scientifically transformed social institutions, according to Neurath, should produce a greater “sense of social security that is now lacking” (MMM 132)

IV. “Collectivization” of Life

Modern Man in the Making’s furtherance of rationalized social reform would have resonated with an American audience, especially those who had experienced the impact of Scientific Management on New Deal policy making throughout the 1930s. Whether the efforts of managerial minded social reformers were successful or not, Scientific Management offered tools for economic recovery and social cohesion along the lines Neurath mentioned in Modern Man in the Making (MAI 260–62).

That same audience had to contend with radical changes to everyday life—especially work, leisure, home, and family life—as it was being reconfigured by modernity. In Modern Man in the Making, Neurath drew a correspondence between the social concept of “‘only child’ [as] an urgent modern problem” in the Netherlands and the rise of kindergartens, playgrounds, and other social institutions (MMM 113–14). In “Man’s Daily Life,” the final section of his book, the text enumerated data collected from statistical atlases and yearbooks. Neurath touched on the growing population of working mothers, industrialization, women’s suffrage, labor and leisure time, sporting event attendance, militarization of public and private life, travel, prolongation of life, household technologies, and falling church attendance. He asked, “What do all these trends towards modernity mean in man’s daily life” (MMM 113)? Appearing at strategic intervals throughout the layout of the book, ISOTYPE charts vividly presented a range of statistical facts that seemed to answer that question. The combination of statistical charts provided readers with a schematic map with multiple views—or visualizations—of socially organized human life.33 His account provided readers with insight into the waning of a premodern oikos, or the shift from a social emphasis on family and home to a modern economic emphasis on population overseen by a managerial class.

The problem of the “only child” prompted Neurath to speculate on the role that managerialism might play in the social organization of a child’s life. “The ‘only child’ does not easily learn within the family how to adapt itself to its environment. Hence kindergartens are necessary not only for modern pedagogy in general, but also for mental hygiene” (MMM 114). Traditionally, large families took on the role of early education. But, as Neurath observed, a decrease in birth-rates obsolesced familial “collective educational groups” (MMM 114). In addition to other significant factors, namely two working parents, there was an increase in the “support all kinds of children’s communities,” such as kindergartens, playgrounds, and alternative institutions intended for children (MMM 114). Therefore, family elders who previously were responsible for guiding children in strategies of environmental adaptation were replaced by experts in childcare. He concluded, “This collectivization of the life of children is connected not only with the trend in the birth-rate but also with other changes” (MMM 114). By “other changes” Neurath meant to indicate a general trend toward secularization in the West.

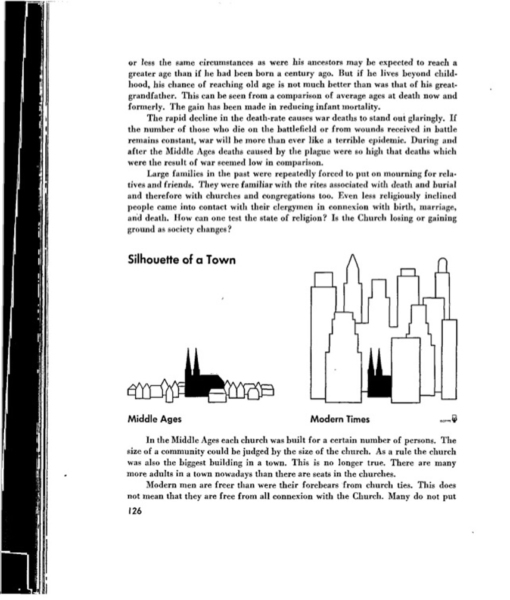

Children collectivized under the organizational oversight of experts in childcare was, according to Neurath’s social-physical calculations of the impact of modernization, correlated to the decline of religious observance. In the concluding passages of “Man’s Daily Life,” a series of charts compared population rates with the increasing decentralized role of the church in contemporary life. Using all of this data and more, Neurath presented his fundamental point: dwindling birthrates correlated to the waning influence of religion in the modern world. Neurath and his team visualized this transition—what he referred to as a liberation from “church ties”—with a pictographic comparison of a town in the “Middle Ages” and a city in “Modern Times” (fig. 3) (MMM 126). The comparative depiction of both eras features a silhouette of a cathedral, with the latter dominating the buildings that are arrayed around it and the latter dwarfed by surrounding skyscrapers. Neurath’s visual comparison implied that where there was a loss of theological authority there was a simultaneous gain in what he referred to elsewhere as a “scientific world-conception.”34

In the bibliographic appendix of Modern Man in the Making, Neurath appended a reference to the American journalist Walter Lippmann’s A Preface to Morals (1929) to “Silhouette of a Town.” There he quoted Lippmann’s observation: “[Modern man] must be guided by his conscience. But when he searches his conscience, he finds no fixed point outside of it by which he can take his bearings. He does not really believe that there is such a point, because he himself has moved about too fast to fix any point long enough in his mind” (MMM 157).35 Lippmann’s book diagnosed the anxiety of an American public facing the panic raising dissolution of “certainty itself” (APM 19). To the extent that “modern man” had lost “his bearings,” he claimed that this dissipation of a center was due to the waning influence of traditional authority (APM 59). Both Lippmann and Neurath were skeptical of fixed belief. Lippmann veered closest to Neurath’s anti-foundationalist philosophy—a Whiggish concept of perpetual epistemic renewal—where he advocated for a rational morality akin to self-discipline.36 Like Neurath, Lippmann believed it a gain for human progress to be released from the dogmas of theology. And, like Lippmann, Neurath too ventured to propose principles that lent coherence and direction for modern living. Both writers agreed that a scientifically educated managerial class was best situated to school a public in rational morality commensurate with a modern social sphere.

Neurath’s account of modern progress—namely the demise of theological thought in the West—was consistent with his program to ban metaphysics from philosophy, sociology, and economics. Neurath’s “world conception” provided the groundwork for his establishment of a physicalist approach to all three fields. For Neurath, a physicalist approach refuted the idealistic-metaphysical current of his era—more commonly known as Geisteswissenschaften—a science of spirit. The physicalist thing-language of his statistically grounded sociology was meant as a deflationary tactic aimed at Geisteswissenschaften, an approach that Neurath hoped would overcome a pointless a priori metaphysics (SWC 45). For Neurath, the natural sciences provided the appropriate starting point for his ongoing production of a unified world conception, a concept that would eradicate the misguided profundities of “spirit” and other fallacious abstractions. He preferred more “empirically meaningful concepts as offer, demand, export and import, warfare, emigration, etc.” (SWC 44). His was an approach “without a world-view” that endeavored to confront “‘world-views’ of all kinds.”37 Importantly, Neurath’s anti-metaphysics entailed the rejection of a lingering “residue of theology”—what he took to be a habit that filled a gap between an ostensible invisible structure and a concrete experience.38

In response to the decrease of theologically inspired Geisteswissenschaften and an increase of a general “technical organization” of all things, Neurath invoked Scientific Management as presenting a guiding principle. On this point, Neurath wrote:

Ethics, which dealt formerly either with the laws of God or at least with laws “an sich,” in other words, laws from which in a certain sense God had been eliminated, is now supplanted by inquiries which make it possible for man to attain happiness by definite arrangements or definite methods of conduct (behavior). Instead of the priest we find the physiological and the sociological organizer. (PVC 50)

Neurath’s use of the term “an sich” was a thinly veiled reference to Kantian enlightenment liberalism in his account of what was displaced by “the physiological and the sociological organizer.”39 This newly installed organizer—or manager—followed the natural sciences. Organization and its oversight were not to be based on what one ought to do but based on an empirical account of what is. As he went on assert, “No science can teach what ‘should be done;’ it can assert only that because A and B have happened, a very definite C follows” (PVC 50). Neurath compared the ethical-causal equation to a machine “tested to measure its lifting effect” (PVC 50). Such an approach involved “engineering, gymnastics (hygiene) and the social technology of today, all of which have an influence on scientific management and commercial organization and thus on human life as a whole” (PVC 50).40 This view was commensurate with the influence of Marx and Engels and their materialist conception of history on Neurath’s physicalism and his scientific world-conception.41 Neurath took their concept of history—the abolishment of the past based on a grouping of contemporary propositions—“as a strictly scientific way of looking at things” that posits “testable assertions.”42

V. Conclusion: Managerial Mind

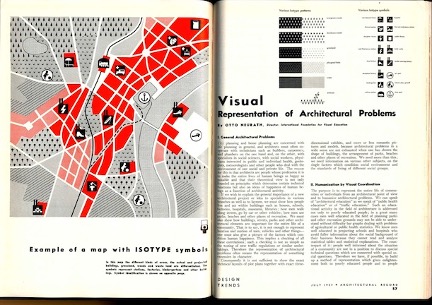

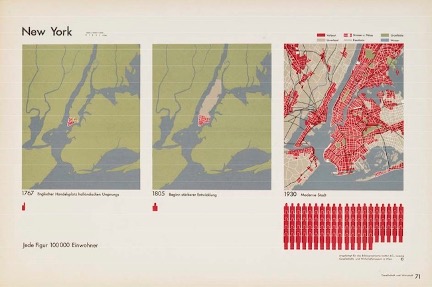

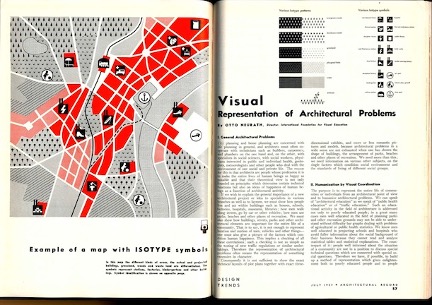

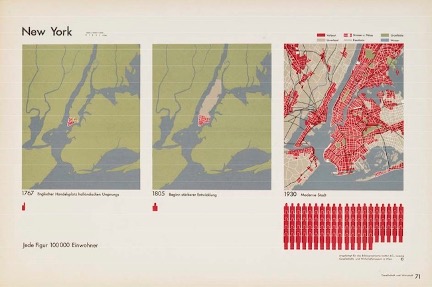

Managerialism had yet to win the day in 1939. Was this a testable assertion in the form of ISOTYPE? If it was the case that the decline of church attendance resulted in the rise of a new clerisy in the form of a managerial class that increasingly attended to all aspects of social organization including the “collectivization of the life of children,” then it was likely that kindergartens, playgrounds, and other childcare institutions were symbols of modernity. In 1937, Neurath and his team had designed a cartogram of a fictional modern city, in order to demonstrate the ISOTYPE method applied to urban planning (fig. 4). The cartogram was featured in his article, “Visual Representation of Architectural Problems,” which appeared in Architectural Record.43 The cartogram featured factories, kindergartens, playgrounds, and other urban structures (but, significantly, no churches). The cartogram charted the expansion of managerialism in keeping with what could be referred to as the Taylorized city. Neurath and his team could have designed a similar cartogram for a city in the United States to include in Modern Man in the Making, perhaps drawing on data that was used for the cartogram of New York City included in Gesellschaft und Wirtschaft atlas from 1930 (fig. 5). If this had been the case, Modern Man in the Making would have supplied readers with the transcendent view of the social engineer. Readers could have tested Neurath’s cartographic assertion in the form of an ISOTYPE against their experiences in urban spaces across America.44 The addition of a cartogram, however, would not solve the problem of Neurath’s conflation of correlation and causality. There simply were too many data points and too little context to have drawn a firm conclusion.45 Instead, Neurath opted to conclude his book with a caution and an ISOTYPE of a skyscraper (fig. 6).

“Skyscrapers are symbols of modern cities, but:” an ISOTYPE of a skyscraper followed, with the colon indicating that the image was meant to be read as a continuation of the text. The skyscraper displays two tiers at its top, and a cut-away shows a missing floor near the lower portion of the building with text that reads: “Where has the 13th floor gone to?” To the right of the text there is a graphic/typographic representation of a section of an elevator control panel. As an example of physicalist thing-language of ISOTYPE, the image was itself an articulation of content that completed Neurath’s thought. What was striking about Neurath’s inclusion of this ISOTYPE was that it stood as an icon of socio-technological achievement and symbolized the fulfillment of managerialism. At the same time, it represented the postponement of the ultimate achievement of managerial rationality in the form of a superstition. In this sense, the image of the skyscraper with its absent thirteenth floor was a reminder to those readers who occupied tall buildings that “modern man” was still in the “making.” Just below the image a new paragraph began: “The life of modern man is not wholly modern. The environment may be the last word in technology, but life itself is shot through and through with inherited ways of thinking and behaving that are centuries old. These are insufficiently analysed” (MMM 131).

Neurath’s ISOTYPE skyscraper accomplished two goals. First, in order to solidify the relevance of the book to a managerial audience, Neurath concluded Modern Man in the Making with an icon of managerial ascent in the United States. The image of the skyscraper was a sure-fire attention grabber because it was consistent with an existing popular cultural imaginary.46 The image of the skyscraper had caught the attention of the American public across a range of media: from displaying feats of technological progress such as Lewis Hine’s photo-essay, “Up From the Streets,” in The Survey (1931) and a photograph of construction workers having lunch high above Manhattan published in The Herald Tribune (1932); to featuring tall buildings in popular films like Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last (1923) and Feet First (1930) and Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy’s Liberty (1929); to John Dos Passos’s novel Manhattan Transfer (1925), to name just a few examples. It was the case that the skyscraper figured into what Roland Marchand has identified as a pictorial formula in American advertising established in the 1920s and that persisted throughout the 1930s. These advertising images, according to Marchand, symbolized the status and authority of the rising managerial class, whose members occupied the well-appointed offices towering over urban spaces.47 By the late 1930s, when Knopf published Modern Man in the Making, urban American readers could turn away from the book in their hands and survey a skyline that expressed managerial concentration in the form of vertically rising corporate offices.48

If read with the above in mind, Modern Man in the Making was an historical account of the concentration of managerial control. “But: …” the corrosive “acids of modernity,” as Lippmann put it, left a remainder from the past (APM 61–63). Cognizance of this remainder posited Neurath’s second goal. The image of the skyscraper signified the deferral of the triumph of managerial rationality in the form of a superstition. To enter a lobby of any number of tall buildings in New York City in the late 1930s would be to confront customs that were both contemporary and archaic.49 A lingering habit of mind was embedded within an icon of technological expertise and managerial control. As Neurath remarked some years earlier, “It is easy to see that our life is full of habits which have no technical basis, which spring only from tradition. … Usually, we grasp the possibility of detaching habits only when we have overcome them.”50 Neurath intended the concluding image of Modern Man in the Making to highlight a detachable habit in the form of a prohibition against the use of the number “13.”

He went on to observe that residual habits and traditions without technical basis persisted into the modern era. And, in the case of the managerial class who occupied the tall buildings of Manhattan, adherents to modern forms of life carried on their avoidance of a “superstitious taboo,” which had its “roots in ancient beliefs” (MMM 131–32). Neurath directed his caution to managers who, in following the up-to-date managerial sciences, may have neglected to reflect on still active ancient beliefs. As Neurath advised, “[N]o scientist can avoid the influence of tradition when he begins his investigations” (MMM 132). Neurath’s appeal to the “scientist” echoed already existing literature and forms of instruction within business management programs. While Drurey had observed that Scientific Management had encouraged “mental change” in laborers (as mentioned above), managers themselves had yet to interrogate the signs and symptoms of their own mental outlook. As Neurath advised, release from the encumbrances of the residue of past beliefs required that a scientifically informed manager rigorously follow a step-by-step transformation of the self. The manager as a modern man in the making was to be, therefore, on the alert for unconsciously held beliefs, which he must endeavor to eradicate in the interest of achieving the goal of suppressing non-technically relevant habits.

As a diagnostic tool, Neurath’s skyscraper ISOTYPE and its use to historicize managerialism revealed that while the managerial class had been emancipated from the orthodoxies of theology and from enlightenment liberalism, they were still subject to the lingering dictates of traditions in forms of magical thinking and superstition.51 In other words, despite the gains made by the managerial revolution, there had yet to be a complete break with the covenantal bonds with the past.

The interpretation of Modern Man in the Making that I propose takes the skyscraper as having obsolesced the cathedral as a beacon of authority. In the wake of an acknowledgement of theological outmodedness and of the limits of enlightenment liberalism—both instances of metaphysics, according to Neurath—the principles of Scientific Management superseded dogma and moral and ethical guidance. As discussed above, it was the managerial class populated by social engineers and those administrators who possessed a scientific conception of the world who took on the responsibility of a “conscious shaping of life,” as Neurath put it.53 The new clerisy was to dedicate itself to a therapeutic process of identifying and eliminating metaphysically grounded habits. In Neurath’s case, this came in the form of his advice to readers of Modern Man in the Making. They should remain vigilant so as not to unconsciously reproduce customs inherited from the past. Guided by the “physiological and the sociological organizer,” progress made in the project of making modern man, therefore, was measured in stages of coming to self-consciousness. The secular ritual of constant self-evaluation and perpetual self-revelation was, no doubt, performed in the offices of personnel departments within corporations, where experts practiced therapies of managerial administration on management.

Notes

nonsite.org is an online, open access, peer-reviewed quarterly journal of scholarship in the arts and humanities. nonsite.org is affiliated with Emory College of Arts and Sciences.