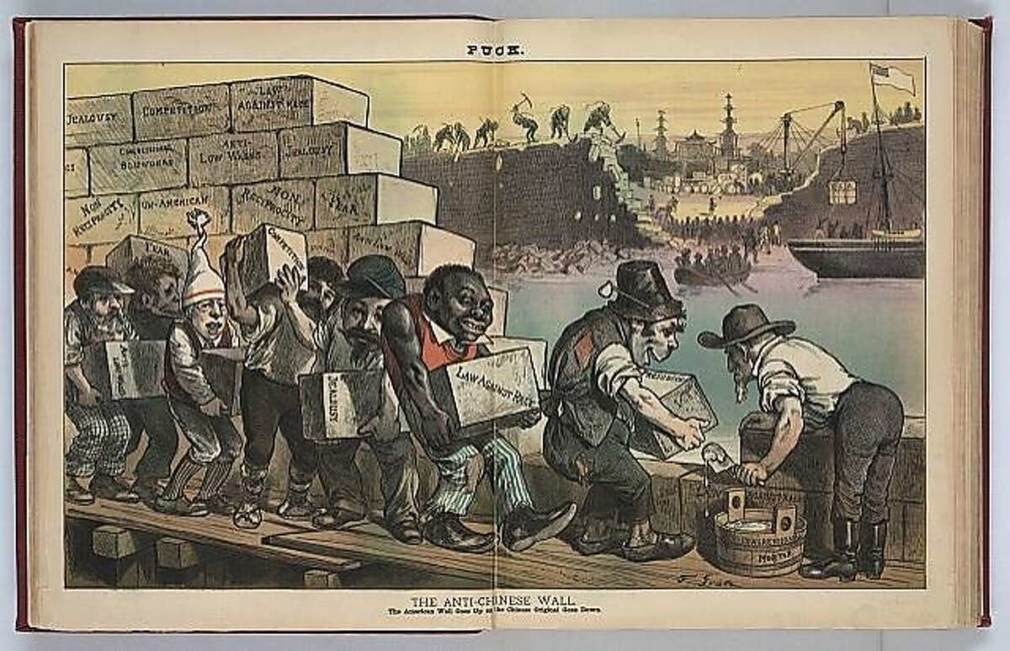

That larger, more insidious effort and its objectives—which boil down to elimination of avenues for expression of popular democratic oversight in service to consolidation of unmediated capitalist class power—constitute the gravest danger that confronts us. And centering on the racial dimension of stratagems like the Cantrell recall plays into the hands of the architects of that agenda and the scapegoating politics on which they depend by focusing exclusively on an aspect of the tactic and not the goal. From the perspective of that greater danger, whether the recall effort was motivated by racism is quite beside the point. The same applies to any of the many other racially inflected, de-democratizing initiatives the right wing has been pushing. With or without conscious intent, and no matter what shockingly ugly and frightening expressions it may take rhetorically, the racial dimension of the right wing’s not-so-stealth offensive is a smokescreen. The pedophile cannibals, predatory transgender subversives, and proponents of abortion on demand up to birth join familiar significations attached to blacks and a generically threatening nonwhite other in melding a singular, interchangeable, even contradictory—the Jew as banker and Bolshevik—phantasmagorical enemy.

Thierry de Duve is one of very few leading figures in recent art theory to make Kant’s aesthetics central to their theory of contemporary art. But de Duve’s use of Kant is both idiosyncratic and controversial. In what follows I try to figure out what, exactly, de Duve believes Kant “got right,” and whether this is: i) plausible as a reading of Kant and, if not; ii) philosophically coherent, independently of its claims on Kant. Coming to a view on the latter also involves asking whether: iii) appeal to Saul Kripke’s theory of proper names helps or hinders Duve’s case.

BY Mike Macnair

Our three authors are all, in very different ways, possibilists. They assume that socialism in some extremely general sense is desirable; but then frame their “what is to be done” entirely by what looks practical in the very short term. But the result in all three cases is practical unrealism: none of these prescriptions are likely to produce anything other than “more of the same” – meaning a labour movement dominated by the right and a left splintered into little pieces, each of which pursues its own “possible” tactics.

The present paper is devoted to addressing the basic asymmetry of a move from what can be called “passive metaphysics” to “active metaphysics,” the overcoming of formalism, structuralism, and semiotics by post-structuralism and its hasty replacement with new forms of thought that presume matter that is alive or animate transparently makes itself available to experiencing subjects, who are affected by it immediately, without mediation, directly. For various reasons, the various forms of thought I will review—historiography, affect, metaphysics—have not cashed out this active metaphysics. But the general orientation remains there, ready to be abused at any time. If postmodernism turned swords into ploughshares, we have recently turned ploughshares into swords.

BY Sam Gindin

This is not a matter of rejecting electoral politics—winning a majority of citizens to radical change through democratic means is fundamental. But coming to governance without a solid social base while the powerful centrifugal influences of capitalism remain in place leads to the disappointments we and others abroad have repeatedly experienced. Without the ability to monitor, check, support, and pressure governments to stay the course, government promises fade. Elections alone become largely irrelevant. Participation in elections may have a tactical role in reaching people, but building the base for social transformation is what is so overwhelmingly central today. Only that will make elections truly relevant down the road.

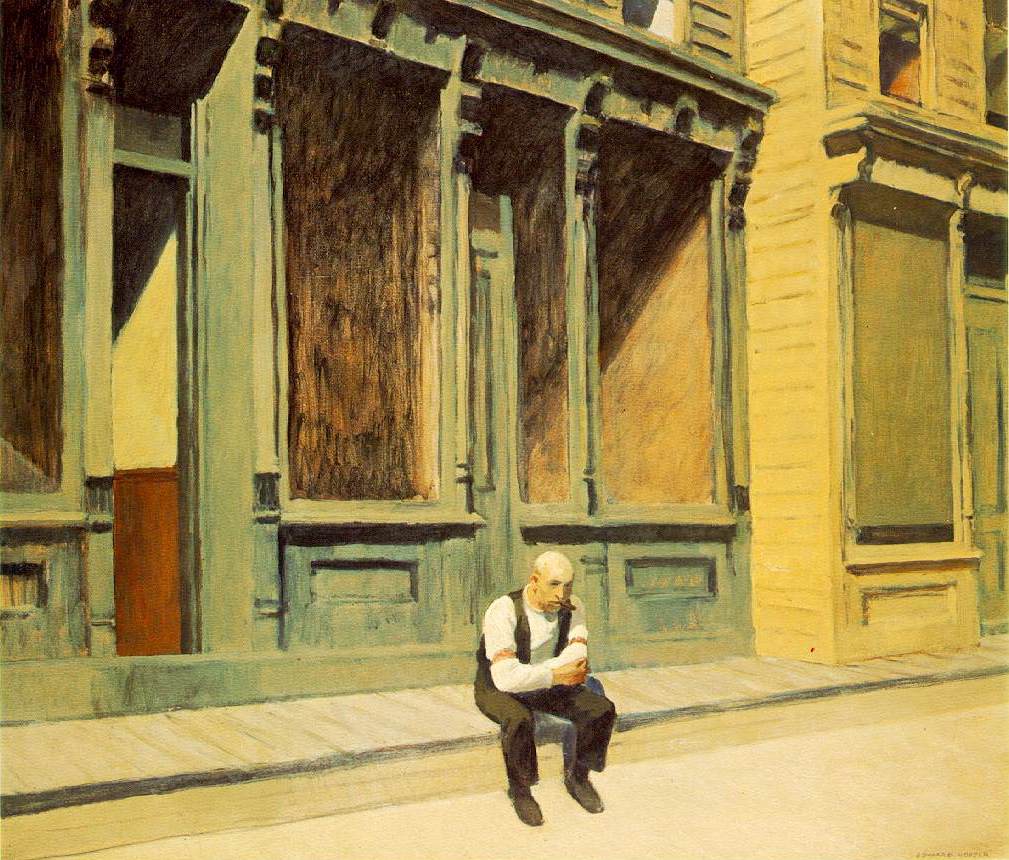

Only rarely does the plan survive the making; more often the sculpture takes over, establishing its own rules, its own reality. Each shape goes down on the paper as an expanse of uninflected, transparent color, the shapes are determined by stencils prepared beforehand. As other shapes are added, the overlapping hues create new densities and new colors. Changing the sequence can further alter these tonal and chromatic relationships, creating new spatial suggestions, so that we read each of these unique images differently.

The causes of this relatively bleak state of affairs is, as Reed and Macnair show, that at the level of civil society the dominant political institutions, parties, or NGO-like formations like BLM only allow citizens with a means of engaging in political life by assuming a standpoint reliant on confused and obfuscatory concepts which preclude an understanding of society in class terms.

Together with the sharp-edged quality of the shapes, the intensity of the color-juxtapositions, and the interplay between the shapes with minimal thickness and the ones backed by PVC, the layering adds a note of enhanced plasticity to the ensemble. Put another way, the “Shards” are at once intensely “pictorial,” for reasons already given, and intensely tactile, which is to say that one’s perception of the “Shards” veers continually between a sense of their strength as compositions—as if in the flat—and their presence as a special sort of material artifact, their character as an entirely new variety of relief.

The dominant economic class has always been at the motivating center of the spread of racial antagonism. This is to be expected since the economic content of the antagonism, especially at its proliferating source in the South, has been precisely that of labor-capital relations. The biological difference of color provides a concrete symbol upon which attitudes of fear and hate might be anchored. The dominant class, furthermore, has been explicit in its terms of living together in “peace” and harmony with Blacks. Its pivotal condition has been that the latter be content to work hard, willingly, and unorganized. “Love” tends to vanish as soon as Blacks begin to show signs of unionization, of movements for normal political status, and of desires to bring themselves up to cultural parity.

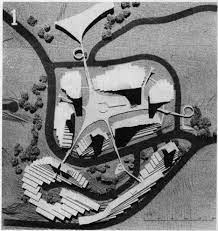

Architectural history is replete with visionaries, those creatives with the singular capacity to conceive and represent visually the default tension of the discipline to constantly reformulate its own norms. Their function is as structural for the evolution of the field as it is statistically bound to yield minimal built results. The extraordinarily rapid ascent of Polish-born American-based Jan Lubicz-Nycz (1925–2011) and his equally precipitous descent into oblivion falls squarely into this singular dynamic.