Greenberg on Dzubas

It’s important to understand that for the greater part of thirty years, Greenberg believed in this artist. But by 1977, his claim was that Dzubas had yet to construct a solid foundation for his future artistic development; that he had failed to “follow up on his achievements and achievedness”; that, instead, he had “let it all lie scattered.”

Chuy for Mayor

Most readers will know that Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, a longtime progressive and respected elected official, after deciding to enter the mayor’s race at the urging of Karen Lewis, the Chicago Teachers Union President whose illness prevented her from running herself, forced Rahm Emanuel into a runoff. Many of you no doubt also know that in a recent poll Chuy scored in a virtual dead heat with Rahm with the election a few days away, on April 7.

The Real Problem with Selma : It doesn’t help us understand the civil rights movement, the regime it challenged, or even the significance of the voting rights act

The victory condensed in the forms of participation enabled by the VRA is necessary—a politics that does not seek institutional consolidation is ultimately no politics at all—but not sufficient for facing the challenges that confront us in this moment of rampant capitalist offensive against social justice, but neither are the essentially nostalgic modalities of protest politics often proposed as more authentic than the mundane electoral domain. It is past time to consider Prof. Legette’s aphorism and engage its many implications. And that includes a warrant to resist the class-skewed penchant for celebrating victories won in the heroic moment of the southern civil rights movement as museum pieces disconnected from subsequent black American political history and the broad struggle for social justice and equality.

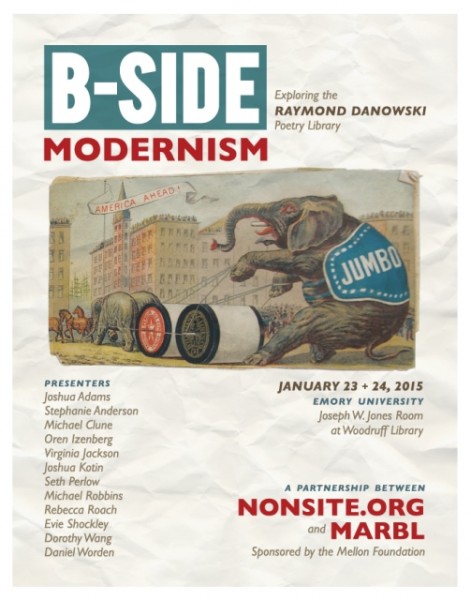

B-Side Modernism: At Emory University, January 23-24

B-Side Modernism is almost here. For more information click on the image below or visit our events page.

The idea behind “B-Side Modernism” is to consider the work of 20th century poets and artists whose meaning and value have yet to be fully realized. The Raymond Danowski Poetry Library at Emory University is an amazing resource; more than any other collection, it represents the richness and diversity of English language poetry in the 20th century and beyond. For nonsite.org, the collection – and the Mellon Foundation’s support of this project – presents a fantastic opportunity, not just to support new scholarly work, but to open up a major archive to meaningful public conversation.

B-Side Modernism

In June of 2014, nonsite.org, with the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, sponsored four fellows to do research in the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library at Emory University. Danowski’s synoptic ambition—to collect literally all poetry in English published in the 20th century, including the independent journals, short-run chapbooks and broadsides that gave modernism its distinctive energy—has created an opportunity to examine the materials out of which our accounts of the century have been made, without the influence of a shaping hand.

The work of our B-Side Fellows, presented here, takes the shapelessness of “everything” as a provocation to investigate the divergences between canonical accounts of modernism in poetry; to explore the many roads not taken, whether they manifest in the unedited arc of a career, in the one-off achievement, or the unclassified ephemera of a moment. What else might modernism have been? And how do such reconsiderations of modernism bear on what happens on the flip side of the mid-century divide? Edited by Jennifer Ashton and Oren Izenberg

Hearing the Tone of the Self: Toward An Alternative Ethics of Translation

Attunement and transaction — rather than forcible replacement— are the preferred metaphors here for describing a good translation. And neither “attunement” nor “transaction” invokes a scenario in which something is being forcibly or forever transformed or deformed into something else.

“Crowded Air”: Previous Modernisms in some 1964 New York Little Magazines

Like Ed Sanders’s antagonistically and aptly named Fuck You Press, whose publication list includes bootleg mimeograph printings of W.H. Auden and Ezra Pound, little magazines from 1964 serve as case studies for an avant-garde scene that grapples with the enshrinement of/resistance to previous avant-gardes…and an engagement with social antagonism….Ultimately, these scenes’ interest in social self-documentation is propelled by an attempt to get around the problem posed by the relegation of poems (of whatever aesthetic genealogy) to the cultural sphere.

‘Endless Talk’: Beat Writers and the Interview Form

While we don’t tend to think of William Burroughs in terms of his engagement with the interview, in fact the form underpins much of his (and his collaborators’) work from the 1960s forwards, including the cut-up. Taking the Beat concept of self-interviewing to its extreme conclusion, Burroughs and frequent collaborator Gysin, turn the form’s interrogative function on the artist and the artwork. In doing so they highlight the interview’s potential to be a critically engaged, radical form.

Joe Brainard’s Grid, or, the Matter of Comics

A comic that merely uses Nancy, rather than a painting that appropriates Nancy, does not seek to elevate its subject matter. Instead, as is so often the case with Brainard’s Nancy drawings and paintings, the point is to devalue painting, to turn painting into a valueless form, by folding painting into comics.

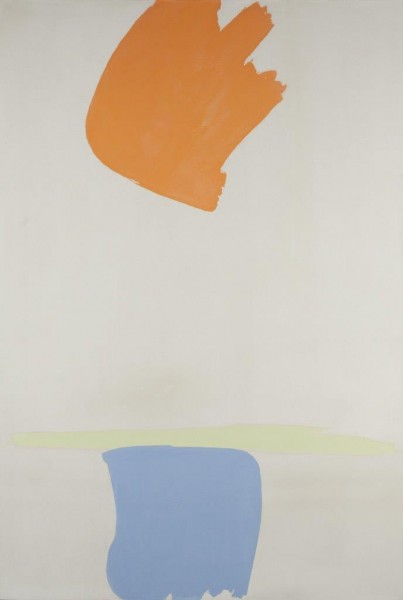

“B-Side Modernism” Exhibition

An exhibition of images from The Raymond Danowski Poetry Library, selected by our B-Side Fellows to accompany the essays in Issue 15.