It will, I want to argue, be hard to describe Owen Kydd’s practice as appealing to the plurality of the medium against Art; on the contrary, it will be better understood as doing just the opposite, as redeploying the idea of the medium precisely on behalf of the idea of Art—and against a pluralism that is not only aesthetic but political.

I do not have this privilege because I have seen the works only on the small screen that, to many of us, is the whole world. These screens in our offices and homes are more isolating than even the whitest of white walls in the most pristine of white cubes. They are much more theater-like than even those small project spaces which resemble theaters—ones in which patrons are constantly walking in late and leaving early—which Kydd presumably meant to reject in favor of placing his works on gallery walls. An increasing number of artists with access to technology and a gallery have made a similar choice.

It has been a defining and enduring feature of photographic discourse up to now that automaticity and automatism have been available to us through photography. An important task for the history of photography will be not just to invoke photography’s automaticity, but to describe—for any photographic work or enterprise it takes up—the nature and importance of its automaticity in that instance or set of instances.

I am going to abstract, here, from the ideas of “automatic” and “automaticity,” and from “mechanism” and “mechanicity,” in order to focus on the following question: how should the idea of “automatism” be understood, and what theoretical resources can be used to illuminate it?

BY nonsite

The following six essays are intended as three exchanges around three topics—the autonomy of the photographic image, automatism, and time and meaning—that will be the themes of three panels in a two-day conference at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, March 13 and 14, 2015.

The conference is sponsored by the museum and by the Mellon Foundation and is being organized by nonsite.org. We are looking for creative approaches to these themes that will engage with works in the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection at LACMA. Send proposals for session papers to nonsite@nonsite.org. Proposals must be submitted by November 15, 2014.

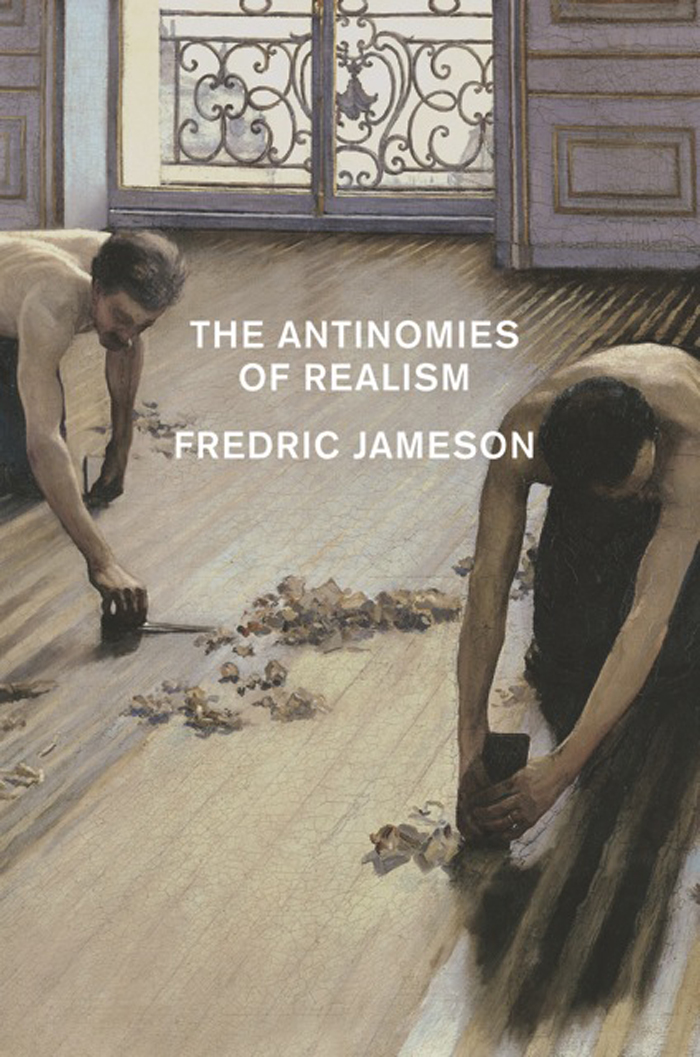

This brings us back to Jameson and realism. Jameson continues to insist upon the idea of meaninglessness in Zola’s abundant descriptive lists; in referring to the copious description of the cheeses in the shop in Le Ventre de Paris, he speaks of “their veritable liberation from meaning in all their excess.” The pungent cheese passage indeed shows a “delirious multiplicity,” but the cheeses are far from being meaningless or “autonomous.” For what does it mean when it is said that an element of a literary work is meaningless? Can it be true that multiplicity or excess leads to meaninglessness? Or that the moment something exists in the bodily realm, it does not signify?

What needs to be understood about my distance from those debates around affect polemics is that I still believe in the binary opposition, and am in that sense, I guess, some kind of structuralist Hegelian, or better still, that I include Hegel in Marx and structuralism in the dialectic. “Oppositions without positive terms”: such was Saussure’s great formula, his reinvention of the dialectic on a linguistic basis. Concepts do not exist in isolation, they are defined by their opposites: it is a dialectical lesson as well as a structuralist one, and in the best of worlds the latter should lead back to the former, which it reinvents in a new and contemporary way.

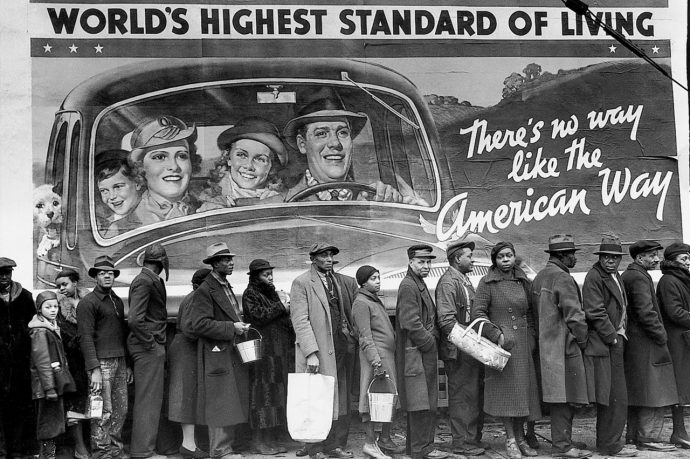

BY Todd Cronan

Once the door had been opened onto the phenomena of the chronically unemployed, it appeared there was no closing it. Which is to say, even though the intervening period—at least between 1945 and 1979—was characterized by something wildly different than rank unemployment, nothing about this fact altered the vision of revolutionary progress centered on the figure of the precariat. It would be fairer to say exactly the opposite. The “affluent society,” as Kenneth Galbraith described it in 1958, was the source of endless lament on the Left (the Right’s attitude toward the growing equality in wealth is another, but related, story).

BY Brian Kane

Nonsite.org is proud to announce “B-Side Modernism,” a research fellowship and conference at the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library (Emory University, Atlanta), starting in late 2013 and continuing in three phases through summer 2015:

Phase 1: A fellowship competition and fellowship residencies for research in the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library in the Emory University Library. Four selected fellows will spend 4-5 days with the early holdings (1910-1945) of the collection and identify a group of specimen texts, some of which will also form the basis of an article for a special feature issue and online exhibition on nonsite.org.

The Call for Proposals for the B-Side fellowship competition opens on October 1, 2013, with full research proposals due on December 20, 2013.

Phase 2: A nonsite.org feature issue, “B-Side Modernism,” slated for late 2014, including articles by the fellows and an online exhibition of the specimen texts from their research. Note: Publication is contingent upon review and approval by the editorial board of nonsite.org.

Phase 3: “B-Side Modernism” symposium, which will involve eight invited speakers at Emory University in mid-2015. Papers are expected to be published in one or two installments as a special issue of nonsite.org in late 2015.

“B-side Modernism” is generously supported by a grant from the Mellon Foundation.

----

“B-Side Modernism”/Raymond Danowski Poetry…