Doesn’t the image’s power lie in its proliferation of meanings? So what is the point of arguing for such autonomy? Is it possible to separate ourselves from all the forces that teach us how to act in a room with an artwork?

Another way of putting this is to say that the violence of the frame consists above all in making our lives as irrelevant as hers, and it’s in this indifference to our particularity (this allegorizing of its irrelevance) that I locate the politics of Kydd’s work.

BY nonsite

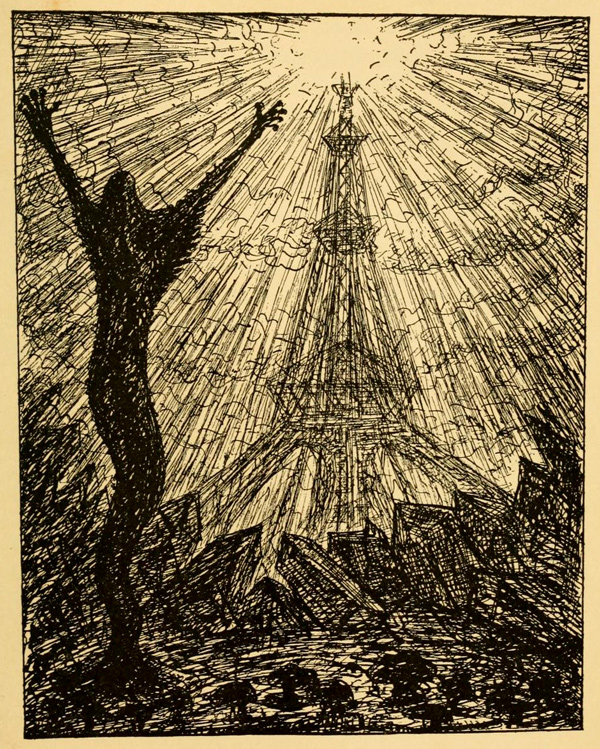

In nonsite’s 12th issue, a collection of views on the meaning and uses of postcolonial theory in and around modern Poland, plus photography and ’sixties Paris and a feature essay on Thomas Piketty’s celebrated Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Study death. Learn it by heart.

Following to the rules of spelling

dead words.

Spell it together

like commonwealth or toadflax.

Do not split it

among the dead.

BY Todd Cronan

For admirers of the work of Walter Benjamin, a translation of Paul Scheerbart’s Lesabéndio: An Asteroid Novel is a major event. Benjamin’s interest in Scheerbart spans the whole of his career, from Gershom Scholem’s gifting him the book at his wedding to an essay on Scheerbart written near the end of his life. Most significantly, Benjamin intended to write an extensive essay on the book that was meant as a fulfillment of the claims set out in “The Destructive Character” and was to be provocatively entitled “The True Politician.” As the Benjamin literature grows, so does Scheerbart’s reputation.

Deschenes then begins to build into the logic of each of her photographs a specific quality – scale, frame, posture, and sometimes color. This is what abstraction means, in case we have forgotten: a work of art does not “look abstract” and it “is” not “an abstraction.” A work of art abstracts a specific quality. Sometimes such qualities derive from observation: a subject can be abstracted, but that does not mean that it is rendered blurry or otherwise stylistically abstract.

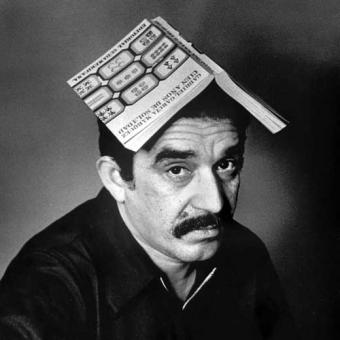

We will have had to forget García Márquez in order to read García Márquez, that is, to read in his texts the chronicle of his own decline and death foretold, and thus to read in these texts the very body of literature itself. That would be the condition of his works’ potential actuality.

The six essays included in nonsite’s 11th issue are intended as three exchanges around three topics—the autonomy of the photographic image, automatism, and time and meaning—that will be the themes of three panels in a two-day conference at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, March 13 and 14, 2015.

The conference is sponsored by the museum and by the Mellon Foundation and is being organized by nonsite.org. We are looking for creative approaches to these themes that will engage with works in the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection at LACMA. Send proposals for session papers to nonsite@nonsite.org. Proposals must be submitted by November 15, 2014.

Photography is—as I hope to demonstrate—radically anti-Cartesian. It shows us that there really is a world, that it wants to be seen by us, and that it exceeds our capacity to know it. Photography also shows us that the world is structured by analogy, and helps us find our place within it….Each of us is connected through similarities that are neither of our making or our choosing to countless other beings. We cannot extricate ourselves from these relationships, because there is no such thing as an individual; the smallest unit of Being is two interlocking terms. There is also nowhere else to go.

BY Todd Cronan

Photography helps us to see and to feel what we are but cannot know. Then again, knowing when to trust our feelings—when we feel them to be right and not just ours—is not just a matter of affect, but of assertion, about what we think others could have meant. Not knowing what they could have meant does not mean they did not mean something or that we cannot know it. Properly acknowledging one’s “kin” requires that we risk the public and corrigible claim to understanding what was said.