Ritual Protest and the Theater of Dissent

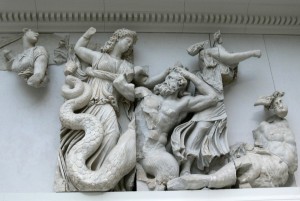

The politics that inform these actions, where not entirely opaque, are based on a semi-spiritual belief that the right recipe of symbolism, passion, and powerful visuals will inspire significant political action that will alter the course of this or that unjust policy or state of affairs. Organizers want to inspire the people who view their protest images on their phones.