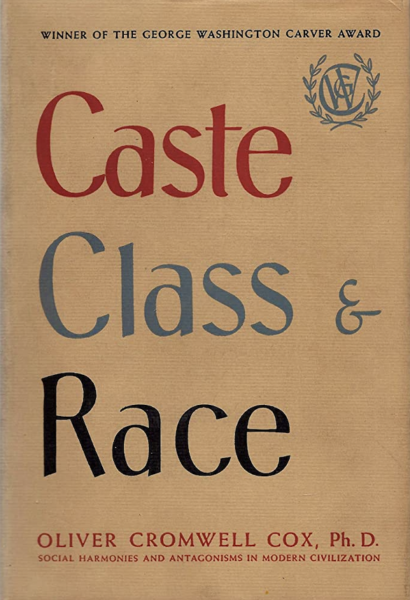

Oliver C. Cox, Gunnar Myrdal, and the Political Limits of Race Relations

From Cox’s perspective, Myrdal falls tragically short at the most crucial moments. Myrdal holds fast to abstractions and to a reformist program where he needed to identify material causes and the overarching requirement of a ruling political class to exploit the labor of the great majority of its population. In a sad but predictable irony, he gave the exploiting class pride of place as the best ally of the dominated caste.

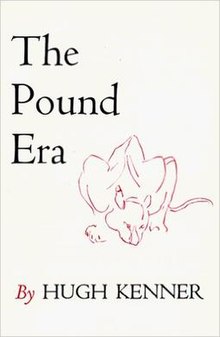

Issue #42: Hugh Kenner’s The Pound Era at 50

In this issue scholars address the underexamined writings of literary critic Hugh Kenner.

Hugh Kenner’s The Pound Era: FAQ

What is The Pound Era about? “How our epoch was extricated from the fin de siècle.” A circle of writers and artists with Ezra Pound at its center: James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, William Carlos Williams, T.S. Eliot. “They were born within a six-year span,” Kenner observes. How poems are made and how they work. How scholarship leads to new ways of seeing: Ernest Fenollosa’s ideogram, C.H. Douglas’s A+B theorem, Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations: “For Joyce’s was the archaeologist’s Homer.” The impact of World War I. The potential of vorticism, the tragedy of vorticism. Defending Pound.

Experience, Criteria, Action, Art

While much has since been written about the relation of mental happenings to outward criteria, that work tends to follow the problem into various kinds of skepticism. Here I want to look at Murdoch’s differently attuned understanding of how inner experience is compatible with Ryle on the ghost and Wittgenstein on public criteria, as well as her occasional interlocutor Elizabeth Anscombe’s account of the relation of intention and action and, in a last section, Hugh Kenner’s elaboration of what T.S. Eliot called the “objective correlative”. In such examples the outer (observable) structure of concepts doesn’t so much block or occlude access to the inner, as invite us to consider what it would mean to think that experience, intention, emotion—to use the words of Murdoch, Anscombe, and Eliot respectively—have an outside structure.

Hugh Kenner and the Visit as Method

I want to say that this tradition of implausible explanations helps us to see why poetry might be a powerful place to think about the problem of historical change: because poems seem like storehouses of precisely the kinds of action that are hard to see as already legible. They “elude foresight utterly,” and are “occulted from most present sight.” They are a site of action in which the third-person category of meaningful action is encountered where it always and everywhere undertaken: in a resolutely first person form.

Hugh Kenner and the Origin of the Work of Art

This is what Kenner calls the Gulliver game, embodied in its purest form in the Turing game, which identifies what it is to be human with the ability to produce the Goodmanian letters and spaces that would look just like the letters and spaces a human would produce, thereby making the computer indistinguishable from the human. The computer (and here he anticipates John Searle’s Chinese Room argument, which makes sense since Goodman’s idea of a text is a syntax independent of any semantics) is the most advanced player in the you’re not allowed to understand what you’re talking about game.

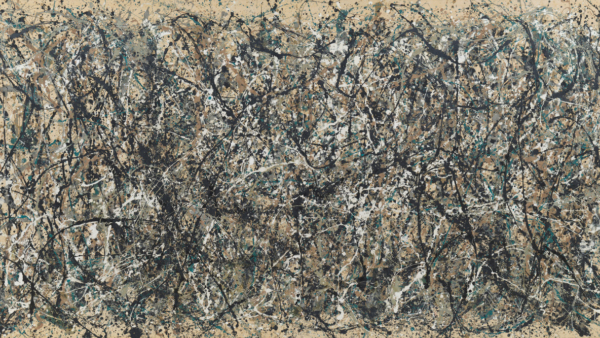

Syntax in Santa Barbara

On the one hand, the eruption of materiality into the representational artwork so vividly illustrated by the Hartpence story will put modernism into motion—it will be “the exact place … modern art began.” On the other, the totalization of this materiality will threaten, as we’re beginning to see, to spell modernism’s end.

“I Don’t Do What Happens”: Hugh Kenner’s Theory of Action

So if it is the case that, as Anscombe says, “I do what happens,” then Kenner’s project is to explore a mode of artistic production that hinges precisely on the point where what happens purposefully occludes what someone is doing. Kenner describes the “principal component” of Eliot’s dramatic method as “his unemphatic use of a structure of incidents in which one is not really expected to believe.” In other words, he builds a counterfeit world for his characters. When we come to categorically not believe what is happening, we begin to think about what they might be doing, “thus throwing attention on to the invisible drama of volition and vocation. The plot provides, almost playfully, external and stageable points of reference for this essentially interior drama.”

Kenner as an Eliot Fan

Even for a reader who cares not a whit about Emily Hale the historical person, the letters, in pointing out sources and underscoring potential autobiographical readings, further point to the fictional nature of Eliotic impersonality. It is both a fiction in being impossible (i.e., a poet can’t write something and truly divorce the writing from the life) but it’s also a fiction-making process, because it mirrors the creation of narrative fiction, where an author imagines works not confined by real events. Kenner’s “invisible” poet is a product and author of fiction.

Four Poems

:: your message is of ordinary length :: so you may be assured of its delivery within the year :: providing we have not so bad a mud season as may depress the mules