Although we rarely speak of the “infrastructure” of nineteenth-century British painting, historians have long been concerned with many of its core elements: the institutions through which artists trained and exhibited works, the social circuitry of patronage, the colonial and mercantile arteries through which art supplies were sourced from around the world, and the networks of printmakers and vendors through which printed reproductions were disseminated. One reason we don’t describe these elements as “infrastructure” is that the term would have been unrecognizable to those involved. The word didn’t emerge until the late nineteenth century and wasn’t commonly used until the early twentieth century.1 To speak of the “infrastructure” of nineteenth-century British painting nonetheless allows certain features to surface more clearly for us now: the physical scaffolding that facilitated the circulations of artists and artworks among a whole host of related human and nonhuman things, as well as the embeddedness of this infrastructure itself within multiple interacting systems. It can be narrowly defined in terms of the “hard” infrastructure of physical systems, described by Brian Larkin as the “built networks that facilitate the flow of goods, people, or ideas.”2 But “soft” infrastructure can also designate immaterial networks, as in another definition offered by Larkin: “things and also the relation between things.”3 We might therefore glimpse hard infrastructure in the painted canal system of John Constable’s The Lock (fig. 1), while also recognizing the soft infrastructure of the institution (the Royal Academy) through which that painting was exhibited and sold. Infrastructure even transformed the luminous contours of Constable’s world: the streets, shops, and theaters around the Royal Academy were increasingly lit by gas lamps supplied with gas through extensive networks of underground pipes.4

Infrastructural technologies—particularly associated with steam-powered transit and manufacturing—enabled the colonial expansion, urbanization, and industrialization we now regard as synonymous with the emergence of “modernity” in nineteenth-century Britain. While art historians have often remarked upon the conditions of industrialization in Western Europe and particularly the reorganization of labor and class, infrastructure names an essential but underrecognized component of that transformation. As indicated by the prefix infra—“below” in Latin—infrastructure typically lies beneath the visible surface. Even when it is visually present it is designed to evade our conscious attention.5 This article takes seriously the logic of infrastructure as both a material feature of nineteenth-century British modernity and as a conceptual framework that aspires to the frictionless transit of materials, people, information, and economic value across space. The accelerating circulation of information, of images, and of commodities across Europe and its colonial networks required various forms of physical scaffolding which dictated the parameters of how things could circulate.6 Media histories have been exceptionally alert to this dynamic.7 Inspired by such work, by research in environmental history, and by recent scholarship on contemporary art, might the idea of infrastructure permit us to apprehend a broader dynamic developing at this moment?8 Did the nineteenth century bring with it new possibilities for what it could mean for an artist to work and to think infrastructurally?

To sketch out some of the forms this may have taken, I focus on one of the most literally infrastructural artists of the nineteenth century, John Martin. Best known for his spectacular historical landscapes and popular mezzotints, Martin was also a prolific amateur engineer. In many regards, Martin was an atypical artist: never admitted to the Royal Academy, he enjoyed periods of intense public popularity but was also criticized for pandering to middle-class tastes.9 His epic paintings of destruction coupled intense atmospheric effects with the careful rendering of precisely measured architectural formations—a conjunction that left his artworks somewhere between the sublime and the actuarial.10 Yet Martin was also intensely “of his time.” His obsessive historicism—his extensive and laborious efforts to recreate ancient settings with mathematical exactitude in his artworks—gave pictorial form to a broader Victorian popular interest in the past.11 Foregrounding the infrastructural components of Martin’s work enables us to think differently about both Martin and his contemporary moment.

Because they concern physical systems for circulating people and materials, Martin’s engineering projects supply unusually compressed examples of an infrastructural way of thinking about and picturing the world in the early nineteenth century. But infrastructure, I argue, entails more than this. I take infrastructure to designate a characteristically modern understanding of space in terms of the managed circulation of material and immaterial forces. The concept operates in tandem with the economic imperatives of extractive capitalism. Extraction “names,” in the words of Nathan Hensley, “not just a material practice but an … orientation toward the world … based on use.”12 It is an epistemology of instrumentalization and disposability that requires the physical circulation of people and commodities as well as the metaphorical circulation of economic value. By excavating the infrastructural “stakes” of Martin’s work, we also encounter the metabolic disturbances that were being confronted by an industrializing and carbonizing Britain.

In what follows I revisit three aspects of Martin’s work: his artistic printmaking, his engineering projects, and his large-scale oil paintings. Across them, we can recognize Martin’s modernity as a function of his ability to conceptualize the world in terms of flows and the infrastructure that manages those flows. It included but was not limited to pictorial representations of physical infrastructure. Precisely because infrastructure strives to conceal its operations, I pursue alternative ways we might recognize its presence and in doing so come to apprehend its centrality for early nineteenth-century British art.

Mezzotint Flows

In 1827, Martin produced a mezzotint and etched print (fig. 2) of his first truly successful oil painting, Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still (1816, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Like many of his compositions, Joshua contrasts a detailed rendering of an Old Testament architectural setting with a churning swell of natural and supernatural forces that encircle the scene. Martin’s recently completed mezzotint series illustrating John Milton’s Paradise Lost earned him both critical and financial success. Critics who found his large-scale spectacular oil paintings vulgar or garish were more approving of the prints, which had simplified compositions and fewer architectural details. “When reduced to the mere black and white of mezzotint prints,” one reviewer observed in 1829, the “power of his designs” were “undiminished if not indeed increased.”13 John Ruskin later captured the view of many when he remarked that Martin’s “chief sublimity consists in lamp-black,” referring to the sooty pigment which dominated the mezzotint compositions.14

Joshua is a print that hinges on the drama of circulation. In the center of the composition stands the eponymous leader of the Israelite forces, Joshua, who has been defending the city of Gibeon from attack. On the right, Gibeon’s monumental architecture is illuminated from above by bleaching sunshine. On the left, the dense accumulation of clouds over the receding landscape signals the divine storm of hail and fire that will be brought upon the Amorites as they flee. Martin pictures the moment when Joshua appeals to God to halt the movement of the sun and prolong the solar day, giving him more time to defeat the Amorite forces. When rendered in the limited tonalities of mezzotint, the composition sets the ominous power of divine darkness seen on the left against the creative extrusion of supernatural daylight shown on the right. In other words, this is a narrative in which a human protagonist has endeavored to disrupt the natural cycle of day and night for his own advantage.

Rather than look to the lucid repetition of modular architectural units, I take the infrastructural interest of this print to ultimately reside in its narrative and compositional investment in managing powerful flows. It is the convergence of atmospheric, luminous, and military forces upon the Amorites that will guarantee Joshua’s success. The upper perimeter of the print is dominated by the directional movement of atmospheric forces toward the retreating Amorites. A dense procession of Israelite soldiers spills into the right foreground from Gibeon in pursuit, channeled along a narrow built road. These flows have been activated by Joshua, who further directs the circulation of the planets themselves, albeit through a divine intermediary. Joshua’s appeal to prolong the day takes on particular intensity in the context of a rapidly carbonizing British economy, in which steam-powered combustion was creating a form of labor power that was not constrained by alternating diurnal periods of work and nocturnal periods of rest.15 The radiant intensity of artificially extended daylight seen drenching the city of Gideon likewise recalls the luminous operations of steam-powered blast furnaces used widely in Britain for iron production since the late eighteenth century. These effects were installing themselves in central London, too, through the extension of coal-powered gas lighting on the streets. (“Not a dark corner to be got for love or money,” complains a man in Thomas Rowlandson’s 1802 caricature of the new gas lights at Pall Mall.) Industrial metaphorics aside, the print bespeaks an investment in the conditions of multiple, interacting modes of circulation—and a sense that civilizational survival coincides with and depends upon controlling those modes.

Martin was more attentive than most artists of his stature to the physical systems and material flows through which a print came into being. Spurred by his successful prints of the late 1820s, Martin built a workshop below his studio where he personally engraved and produced impressions of several of his large mezzotints, experimented extensively with new printmaking techniques, and supervised the assistants who printed the rest of his output. His print studio, I am suggesting, is one site where we might begin to trace Martin’s investment in devising physical systems for enabling and directing circulation. As his son Leopold later described it, the workshop contained: “fly-wheel and screw presses of the latest construction; ink grinders, glass and iron; closets for paper; French, India, and English drawers for canvas, blankets, inks, whiting, leather shaves, &c.; out-door cupboards for charcoal and ashes ….”16 This was a complex setting designed by Martin which comprised large devices operated by rotaries and shafts, industrial products such as iron, and industrial by-products such as ash. Although he was hardly the first artist to maintain his own print studio, Martin’s attentiveness to the technical specifications and physical systems through which prints come into being resonates with a broader set of preoccupations in his artwork and his engineering projects.

Martin was particularly known for pioneering mezzotint on large steel plates, which were more difficult to engrave than copper but proved much more durable in the printmaking process. For Joshua, “a large steel plate was procured from Harris and Co.” which was first given a mezzotint ground upon which etching was then done.17 Steel engraving itself was still a relatively new technique that had been introduced in Britain less than a decade earlier. Martin’s great innovation was to employ it for mezzotint and to do so on a physically significant scale—his print of Belshazzar’s Feast from 1826 was the first large-scale soft mezzotint of an artwork. As described by Leopold, Martin would distribute varying mixtures of oils and inks on the plate between each pull as he worked the mezzotint up to its finished state: “at the outset he would pull a plain proof of the plate, using ordinary ink; then work or mix the various inks. First, he made a stiff mixture in ink and oil; secondly, one with oil and less ink; and thirdly, a thick mixture of both ink and oil.”18 The repeated pull of intermediate states was typical of the mezzotint process. What this description highlights, though, is that Martin’s print studio was a space for employing novel technologies and industrial materials in a manner that was newly possible in the early nineteenth century. Martin sourced steel, oils, and charcoal. For example, lamp black, the source of Martin’s “chief sublimity” according to Ruskin, was an ink typically pigmented with chimney soot. It was a cheap form of industrial waste. Martin’s printmaking entailed guiding the interaction of soot and steel, directing how one moves across the surface of the other. Not unlike Joshua himself, Martin managed the distribution of light and dark in his workshop—he could direct the flows of pigmented darkness, draw out fields of luminosity, and when he was satisfied with a given apportioning of light and dark, he could halt the process and affix it to paper.

The Infrastructural Metropolis

Printmaking was also an arena in which Martin envisaged large-scale interventions in the built environment that would create dedicated areas of light and darkness, that would channel viscous flows, and that would facilitate the transit of waste, people, goods, and economic value. The same year that he produced his mezzotint of Joshua he published the first of many engineering plans, which would eventually include a railway circuit linking London’s rail terminals, a coastal lighting scheme for ship navigation, and numerous systems for managing London’s water supply and sewage. As many have noted, Martin grew up outside of Newcastle and was exposed at an early age to coal pits, lead mines, and glassworks.19 Although he received no formal training as an engineer, his brother William published nearly 150 technical plans and inventions and even won a medal in 1813 for his design for a spring weighing machine.20 Martin counted among his friends J.K. Brunel, engineer of the Great Western Railways, and the inventor Charles Wheatstone, whose early experiments with the electric telegraph were witnessed by Martin.21

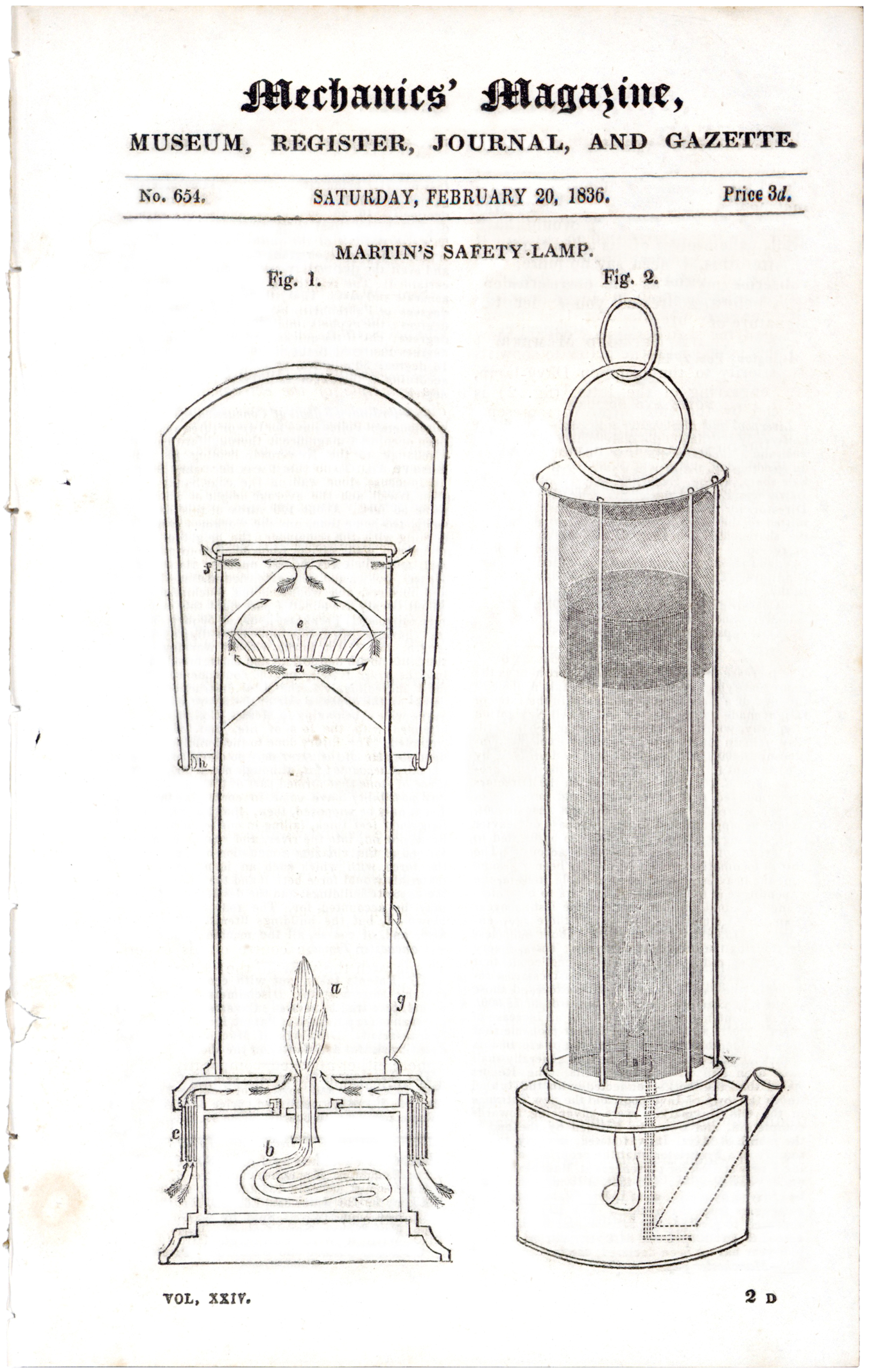

Martin’s own invention for a mine safety lamp exemplifies his investment in the labor conditions of industrializing Britain and more specifically his ability to conceptualize a dynamic field of desirable and undesirable flows which require physical structures to manage (fig. 3). The print shows Martin’s lamp on the left and the famous Davy-lamp on the right for comparison. Mining explosions were known to be caused by the accumulation of “fire damp,” a form of highly flammable methane released by coalbeds. When a concentration of these gasses came into contact with the lamp flames needed to illuminate the dark mine shafts, they triggered large-scale, deadly explosions. Martin’s lamp design disaggregates the desired in-flow of oxygen to feed the lamp’s flame from the undesired ingress of flammable firedamp. The ventilation system at the top of the lamp likewise permits the outflow of the gases released by the flame without enabling firedamp to enter.

In reality, Martin’s plan was unsuccessful: both he and his brother submitted designs for mining safety lamps that were tested for the Committee on Accidents in Mines. When his lamp exploded, Martin immediately withdrew it from consideration.22 Nonetheless the lamp enacts, on a small scale, what I have been suggesting we term an infrastructural form of thought predicated on managing the flows set in motion by modern industry. Here, too, Joshua comes to emblematize the place of the human within such a configuration—firstly in his role guiding natural and atmospheric movements, and secondly in his pursuit of prolonging or augmenting conditions of illumination. The mine shaft was a site in which Martin sought to maintain distinct spaces of light and darkness, not unlike the work undertaken in his print studio. Indeed, the sooty by-product of oil lamps (including the one designed by Martin himself) was precisely what was used to make black ink for printmaking. Illumination within the mine created the material conditions for the picturing of darkness within the print.

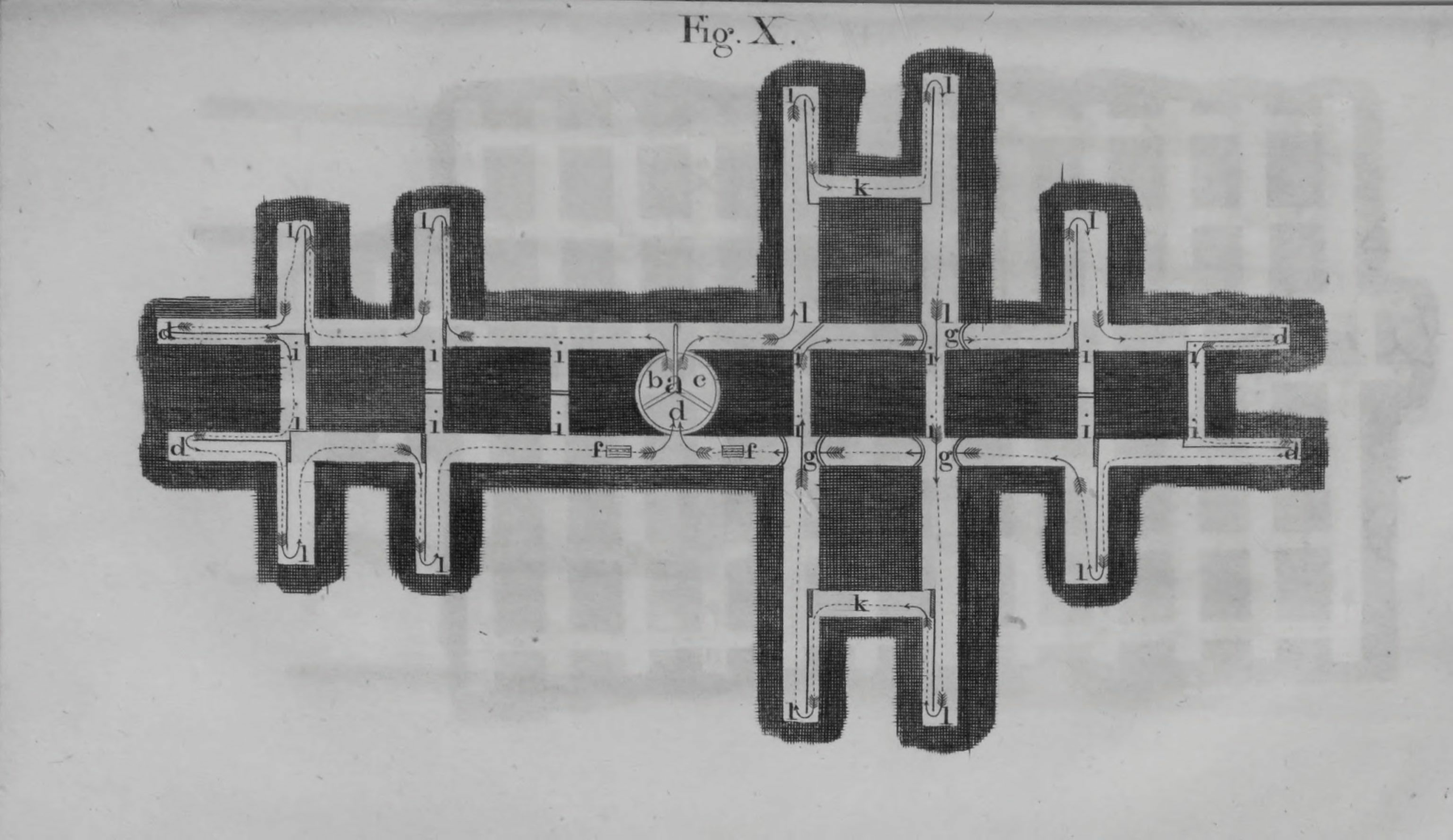

A similar logic was employed in the design of large-scale mining ventilation, which envisioned the unidirectional channeling of air currents. Martin would have been introduced to this subject by his brother William, whose mine ventilation systems and engines John produced illustrations for.23 Martin would go on to publish a plan for mining ventilation in addition to the design for a safety lamp, later testifying for the government’s Select Committee on Accidents in Mines in 1835. The logic is concisely captured in one of the early plans published by John Buddle in 1814 (fig. 4). (Buddle, a proponent of the Davy lamp, repeatedly disagreed with the Martin brothers about some of their rival designs. However, the general principles of mining ventilation and safety were undisputed.) The circular opening designates a partitioned vertical shaft through which air was drawn down into the mine and later expelled upwards. Routed along two linear itineraries in the depths of the mine that are plotted out in dotted lines, fresh air was guided by wooden air-doors, designated in the print by shaded double lines, and would eventually re-enter the vertical shaft—typically fitted with a furnace beneath it to propel the air back up to the surface. Airflow was just one kind of circulation upon which coal mining relied; elaborate transit networks both within the mine and at the surface used interlinked systems of pulleys, pumps, and small railways to transport miners, working materials, water, and extracted coal. In short, like many of the growing industries of early nineteenth-century Britain, mining relied upon multi-level systems for managing the movement of both visible and invisible entities. It further required the measured interaction of surface and subsurface worlds.

Mining ventilation systems, located deep beneath the earth’s surface, typified the self-concealing operations of nineteenth-century infrastructure. However, infrastructure did sometimes entail highly visible interventions into the built surface of the physical environment. Prominent metropolitan building projects included the construction of New London Bridge beginning in 1824, the steady extension of railway lines, gas-powered street lighting that quickly spread across central London from 1807 onwards, and the transformation of London’s docks from 1802 to 1828, to say nothing of the major urban planning projects underway in the growing cities of Edinburgh, Liverpool, Glasgow, Newcastle, and elsewhere.24 One of the half-dozen docks that were built during this period, the West India Docks of 1800 exemplify the imbrication of modern transit infrastructure with colonial commerce: with imports on the right and exports on the left, these two docks enabled Britain’s trade in sugar, tobacco, cotton, and other valuable commodities produced through enslaved labor in the Caribbean (fig. 5). Daniell’s aquatint emphasizes the rational linearity of the scene, with bright and uniform warehouses bordering each dock. The reflective light blue surface of the Thames evokes the fantasy not only of an immaculate urban waterway but also the ease of smooth transit across the physical itineraries of the empire and the metaphorical space of the marketplace. A print like this serves as a vivid reminder that images we tend to classify as “British landscapes” were often characterized by and took as their subject matter the built infrastructure of a modernizing capitalist economy predicated on the extraction and circulation of resources across colonial networks. To move through the urban spaces of London entailed locating oneself within enormous multi-level systems for managing the movement of people, commodities, energy sources, and waste.

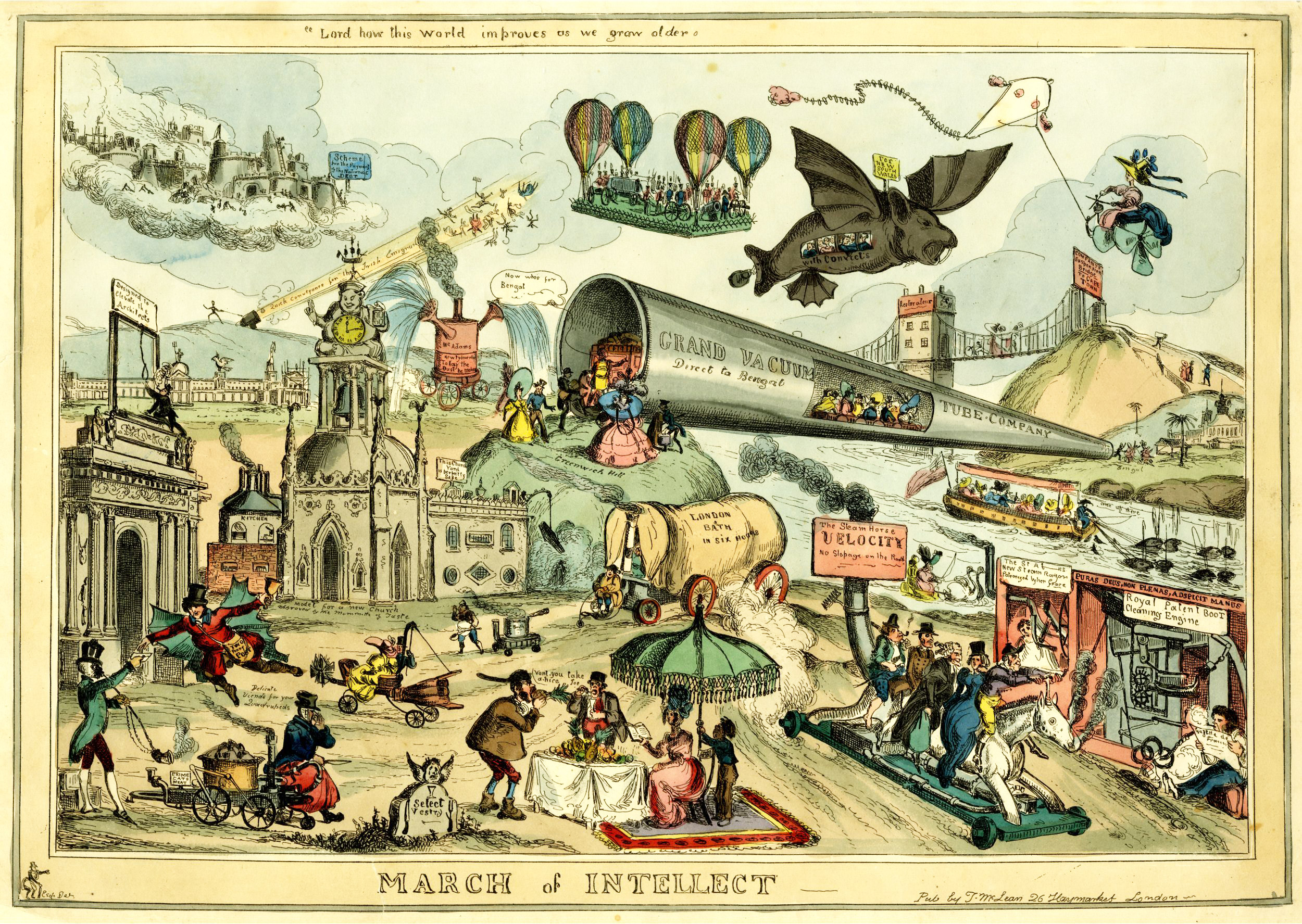

William Heath’s famous series March of Intellect captured some of the sinister aspects of this configuration (fig. 6). Like Daniell, he portrayed a physical environment that was dominated by transit systems. Heath likewise evokes a sense of intimacy between London and its colonies, although here it is disorienting and threatening rather than orderly and pristine. A telescopic metal tube in the center of the composition offers transit via the “Grand Vacuum Tube Company” from London “direct to Bengal.” A monstrous bat-like creature flying overhead carries convicts to New South Wales in colonial Australia. On a distant hillside, figures are shot into the air out of a cannon that advertises itself as a “quick conveyance for the Irish emigrant.” Unlike the Daniell print or the Buddle mine ventilation diagram, Heath summons a nightmarish vision in which new forms of transit have collapsed the geographical distances of Britain’s empire. More importantly, their movement is not guided along discrete linear vectors; several of Heath’s fantastical modern forms of transit appear to be on the verge of crashing into one another, to say nothing of the Irish immigrants who are literally falling from the sky. This is a scene of metropolitan Britain whose infrastructure is failing to properly manage the circulation of people and forces.

What the Heath and Daniell prints ultimately share is an experience of emergent modernity characterized not by industrialization in a generic sense but by the practical and aesthetic presence of infrastructure—infrastructure in the narrower sense of built systems for enabling and managing the movement of commodities, people, energy, waste, and other materials. It is from this vantage point that I propose we revisit John Martin’s engineering projects, and specifically just one of his plans for improving London’s supply of drinking water and its disposal of human waste. Although some of Martin’s designs incorporated railways and docks, it was with the water and waste infrastructure of London that Martin primarily occupied himself, eventually attempting to form multiple failed joint-stock companies to enact his plans.25

Martin and Metabolic Rift

Controversies over London’s water and waste infrastructure were mounting in the first two decades of the nineteenth century. Domestic sewage was typically collected in cesspits, where it would be periodically emptied by “nightmen” who transported the waste by wagon. It would be sold to farmers and their intermediaries where the waste could be repurposed as valuable manure. The agricultural produce whose growth was supported by manure would later be transported back into the city and consumed as food, where it would presumably be converted into waste once more. Although some forms of this urban-rural exchange persisted into the early twentieth century, it declined drastically in the early nineteenth century as Britain’s cities began producing much more waste than was needed by farms. The advent of flush toilets and the rise of more effective fertilizers (initially bonemeal and later superphosphates and imported nitrogen-rich guano) precipitated the near-total collapse of the market for urban nightsoil by the middle of the century.26 Instead, British industrial agriculture became increasingly dependent upon imported fertilizers that disrupted the nutrient cycle which had formerly sustained the long-term fertility of the soil. In the mid-nineteenth century, the German chemist Justus von Leibig even characterized this depletionary model of British agriculture as a form of theft.27

The disruption of a self-sustaining system in which urban manure supported rural agriculture was later held up by Karl Marx as a paradigmatic example of the destructive effects of capitalism on the relationship between human laborers and the natural world. In a famous passage in Capital, Marx writes that “capitalist production … disturbs the metabolic interaction between man and the earth, i.e. it prevents the return to the soil of its constituent elements consumed by man in the form of food and clothing; hence it hinders the operation of the eternal natural condition for the lasting fertility of the soil.”28 In place of a metabolic system of material exchange with the soil, the human encounters material estrangement from the environment. John Bellamy Foster evocatively termed the development a “metabolic rift.”29 This names a broader category within Marxist and now environmental thought in which self-renewing systems of exchange between human activity and the natural world are catastrophically terminated.30 In the case of London’s waste infrastructure crisis, the existing soil nutrient cycle was derailed, the pursuit of ever-greater agricultural productivity intensified soil degradation, and the accumulation of waste in urban centers produced an ancillary form of pollution: sewage was increasingly directed into the Thames, which was also one of the primary sources of water for portions of the city. (Of course, the formerly metabolic system of urban-rural manure exchange had its problems too—among other things, it propagated the spread of deadly diseases.)

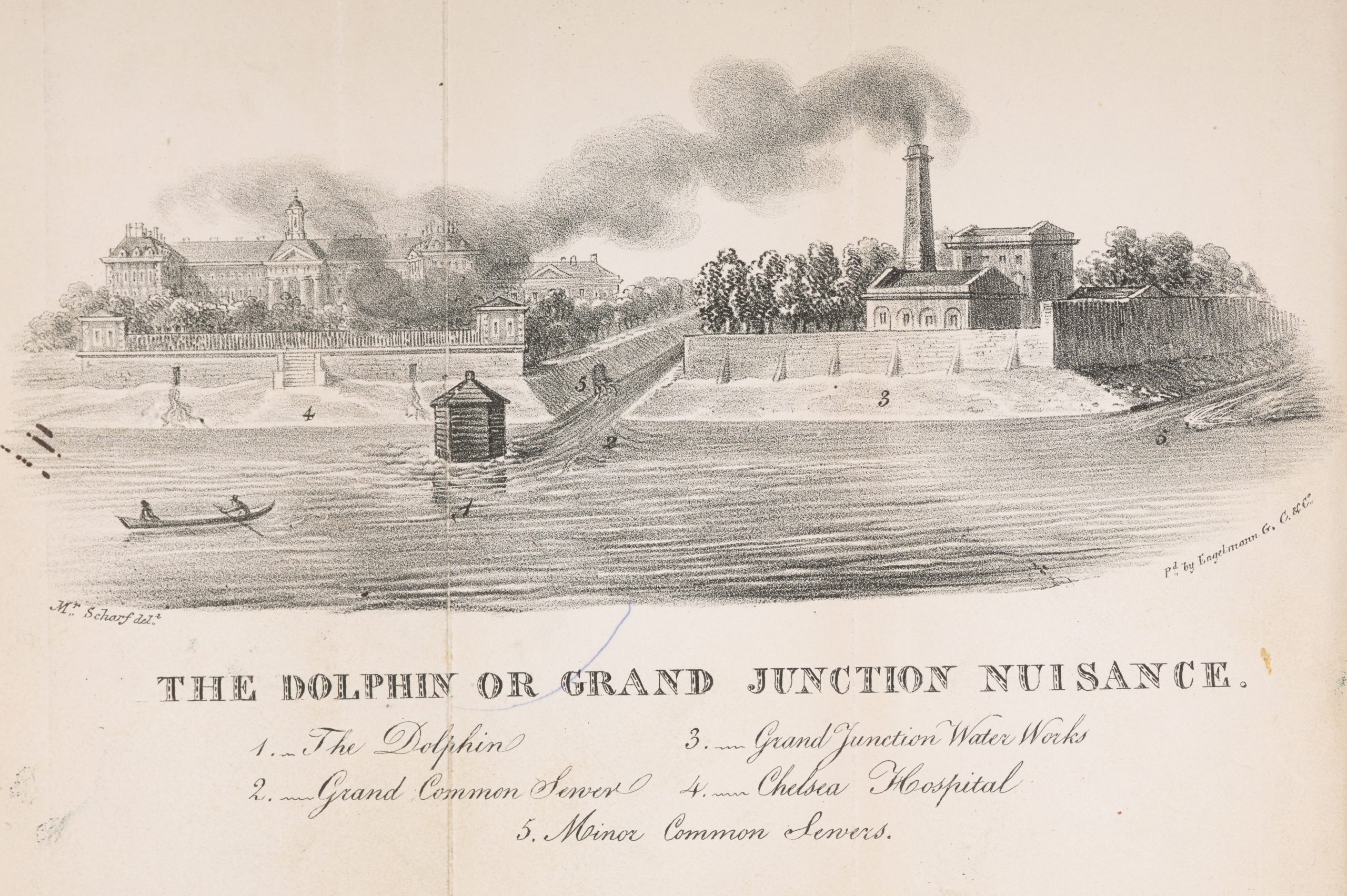

Martin spent roughly two decades publishing a series of plans for improving the water supply and waste management of London (whose history has been most extensively documented and discussed by Lars Kokkonen).31 At various points this included filtering sewage out of the Thames and transporting it via boat to the countryside; sourcing additional water from the Colne river; creating new public urban baths, fountains, and waterfalls; the building of new water towers, aqueducts, and centralized sewage repositories; and a range of designs to prevent sewage from entering the Thames in the first place. Martin’s first plan, published in 1827, was almost certainly inspired by the publication of an incendiary pamphlet that accused the Grand Junction Waterworks Company of sourcing their water just meters from one of the Thames’s large open sewers. The Dolphin; or, Grand Junction Nuisance characterized the water as “offensive to the sight, disgusting to the imagination, and destructive to health.”32 The frontispiece portrayed the company’s in-take pipe in the center, which it described as a “wooden-headed, dingy-coloured, ill-shapen, insidious engine of destruction” (fig. 7).33 To the right, the company’s buildings include a steam-powered pump that draws the water up into its system while also releasing large quantities of smoke onto the grounds of the neighboring Chelsea Hospital shown to the left of the Dolphin. The frontispiece animates the contrasting architectural styles of Sir Christopher Wren’s late seventeenth-century design for the hospital with the plain buildings and tall smokestack of the Grand Junction, although previous water-supply companies had operated on the site as well. The Grand Junction Waterworks Company was among five companies that had held a monopoly on the supply of drinking water to London since 1817, and which the pamphlet blamed for the degradation of its quality. Its water, the pamphlet alleged, was “saturated with the impurities of fifty thousand houses—a dilute solution of animal and vegetable substances in a state of putrefaction.”34 The resulting scandal triggered the creation of a Royal Commission which published a report criticizing the quality of London’s water in 1828. Among the material discussed in this report was a plan from John Martin to create an aqueduct sourcing water from the Colne.35

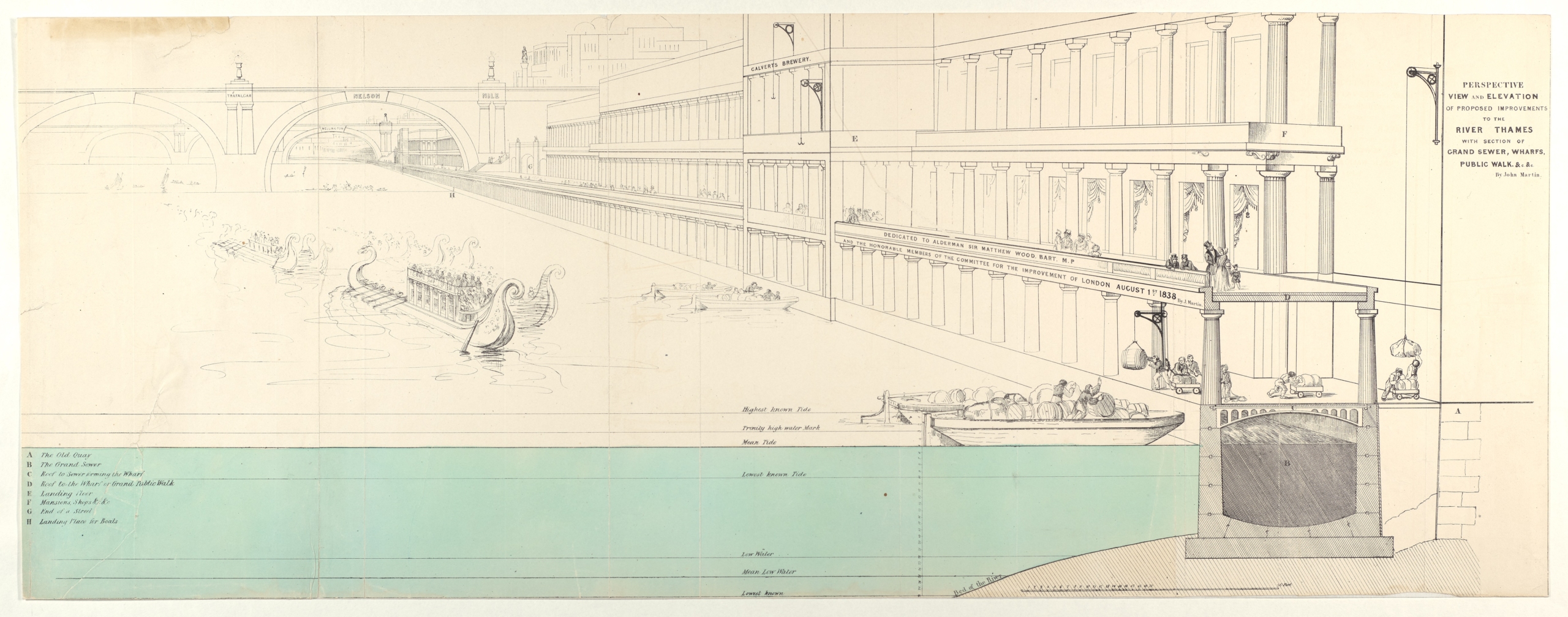

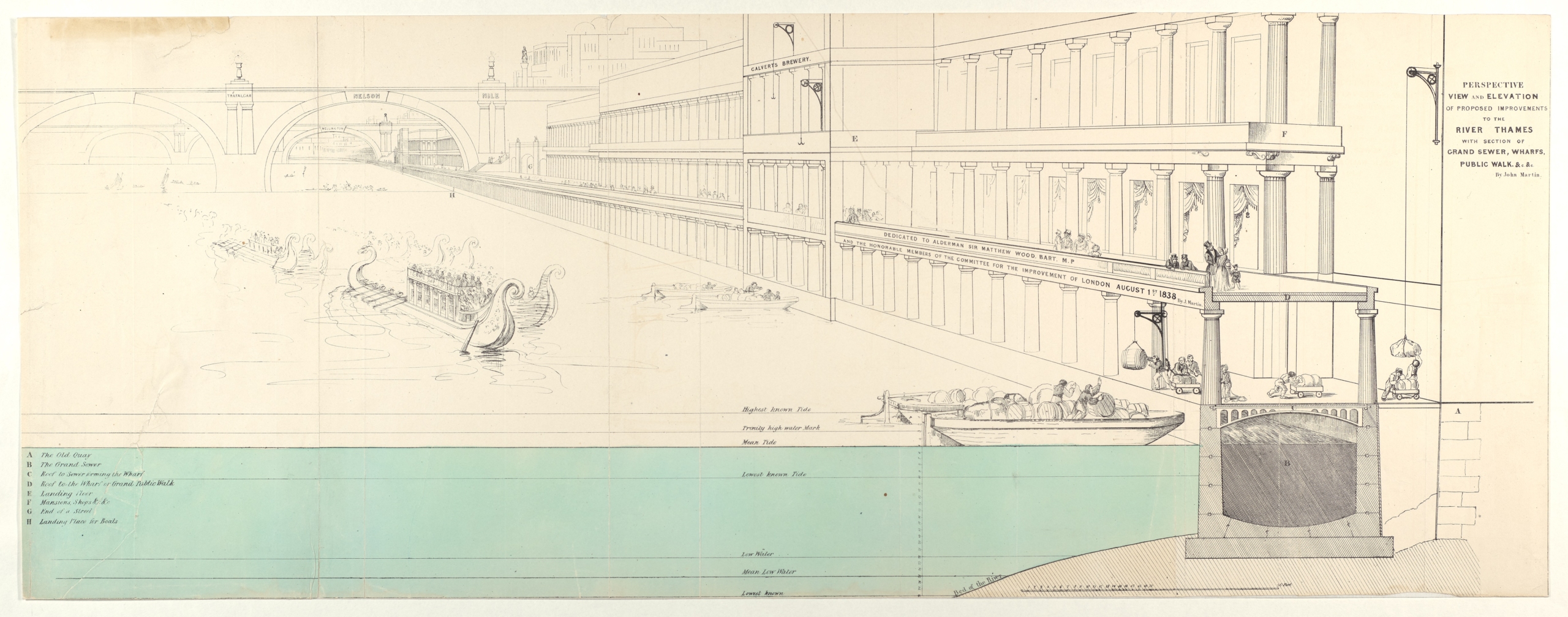

Martin’s infrastructural ambition for London is best glimpsed in a plan published a decade after the first Royal Commission report (fig. 8). He ultimately came to advocate for the complete embankment of the Thames, which would contain two sewers running parallel to the river, wharves for loading and unloading goods, and a grand public walkway. Although his designs were never realized, the subsequent embankment of the Thames overseen by Joseph Bazalgette in the second half of the century included many elements that were originally proposed by Martin. I am not the first to observe certain common features across Martin’s engineering drawings and his artworks—his preferred use of monumental architectural colonnades in both was commented on even by some of his contemporaries.36 Rather than identify visual homologies between, for example, the Joshua mezzotint (fig. 2) and this proposal for embanking the Thames (fig. 8), I propose that we recognize in them an especially infrastructural way of understanding the lived conditions of emergent nineteenth-century British modernity, characterized by human efforts to manage the powerful and potentially dangerous forces circulating around them.

Martin’s embankment print proposes dedicated circuits through which each kind of flow can be channeled, with an emphasis on discrete conduits of unidirectional circulation and the disaggregation of desired and undesired materials. It is a logic that surfaces in his plans for mining lamps, for example, and which likewise finds expression in the systems of mining ventilation that Buddle and his contemporaries were promoting (fig. 4). Although Martin was unusually attuned to the conditions of circulation, he was hardly unique. Like the West India Docks celebrated in the print by Daniell, Martin’s vision for London is a terrain of inflows and outflows, of systems for facilitating the activities of commerce and industrial manufacturing, and of structures that promote the value-generating transit of people and goods.

The embankment print also shares, albeit indirectly, in some of the material dynamics of the mezzotint process in which the artist was so invested. Recall that the metal plate is first roughened all over with a rocker that creates tiny pits that hold ink. The printmaker then smooths portions of the surface back down to create fields of light. Put differently, the dark “ground” of the mezzotint plate in its initial state is an interactive field in which above and below are not stable and distinct positionalities. They instead comprise a single, variegated field. It is the task of the printmaker to restore or reassert a distinction between the surface of the plate and its depths, to create new planar barriers through which pictorial legibility becomes possible. The embankment plan likewise insists upon a new division between the surface and subsurface worlds. It envisions stone expanses that will impose smoothness and uniformity on a formerly varied field, that will enforce the separability of desires and undesired flows. A material terrain of disorderly interactions is segregated into portions of darkness and portions of light.

Martin’s engineering plans for London were responsive to the negative conditions of metabolic rift, although he would have found little common ideological ground with Marx. Not only did Martin endeavor to improve the operation of Britain’s capitalist industries but he was also an explicitly commercially minded artist. Martin himself proclaimed a “strong interest … in the improvement of the condition of the people, and the sanatory state of the country,” which is likewise borne out in his designs to improve the working conditions of coal miners.37 But as Kokkonen has shown, Martin’s plans for the water and waste infrastructure of London were motivated by a desire to “prevent economic waste to the nation,” rather than by a particular concern for pollution or for the soil cycle.38 In spite of this, Martin’s plans did prioritize restoring metabolic properties to British agriculture, going to great lengths to design systems by which urban manure could once again become a cost-effective fertilizer for rural farmers. In one version of his Thames embankment plan, he proposed redirecting the air pressure produced by sewage ventilation to manufactories along the river, another mechanism for recuperating at least partial metabolic exchange between the generation of waste and its productive repurposing.39

Technological infrastructure enabled the conditions of metabolic rift: for example, by making possible the growth of cities, by enabling the transit of food across vast distances, and by intervening into traditional cycles of waste and re-use. It was also called upon to manage the harmful consequences of metabolic rift—for example, through the creation of an enormous multi-level system for disaggregating the inflow of water and the outflow of sewage in London. Although he may have held little in common with Marxist ideology, Martin appears to have been more alert than most to the negative disruption of a system of urban-rural exchange, more anxious than most about failing to harness the latent economic value of waste, and more motivated than most to see in infrastructure the potential for compensatory systems.

The Infrastructure of Experience

Of the many monumental scenes of catastrophe that Martin painted, it is in his Deluge of 1834 that his infrastructural anxieties are most acute—all the more so because the painting omits the elaborate colonnades and finely-rendered architectural settings that have been formerly identified as a point of contact between his engineering interests and his artworks (fig. 9).40 As I have already suggested, an artist can picture things in infrastructural terms without portraying the literal subject matter of infrastructure. We might equally seek out in formal, material, narrative, or even perceptual terms a notion of physical space that is characterized by powerful flows and by human efforts to manage those flows. It requires thinking in terms of systems of circulation and exchange. It both creates and attempts to compensate for the metabolic disruptions of industrial capitalism. Martin embraced industrial capitalism, but he also seems to have been aware that the powerful forces it set into motion required careful management.

The Deluge evokes the failure of infrastructure on a civilization-ending scale. The sole form of transit that will preserve human and animal life, Noah’s Ark, is almost impossible to see, perched atop one of the rocky ledges in the distance. It is perceptually and narratively inaccessible to the viewer. The only space to which the viewer has access is a narrow bluff around which a number of life-terminating forces gather: lightning, boulders, and churning water. The rest of the scene is marked by the absence of systems for managing flows and channeling circulations. That which is meant to be located below (namely, water) swells up above the human figures in the center of the composition. That which is meant to be located far above (for example, the rocky substrate of the mountain on the right) is now tumbling down. It is an environment that is structurally contrasted with the scene invoked in the London embankment print, in which the secure positionalities of above and below are rendered in linear clarity.

The geologist Georges Cuvier allegedly observed this painting while it was in Martin’s studio, praising the artist for picturing a contemporary scientific theory that the biblical Flood had been triggered by the simultaneous presence of the sun, the moon, and a comet.41 (Martin was unusually interested in geology and the nascent field of palaeontology.42) As an astronomical event, it cannot help but recall one of Martin’s monumental scenes from a few years earlier—his painting and subsequent mezzotint of Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still. In that narrative, at Joshua’s urging, the sun and the moon halt their celestial transit, hovering suspended for a day over the scene. Within the original biblical account, this isn’t problematic. When set alongside Martin’s attentiveness to the astronomical causes of the biblical flood, though, other consequences become possible. By bringing the sun and the moon together, Joshua actually creates the conditions under which a civilization-ending flood might be triggered. All that is required is the arrival of a comet. Although this does not itself amount to a metabolic rift, what it shares with that concept is the notion that a self-regulating circuitry that exists in the natural world has been disrupted and that this disruption has self-accelerating consequences that may ultimately imperil the humans who brought it about.

The artist’s infrastructural way of thinking about and picturing the world may have extended to perceptual experience itself. Evidence of this surfaces in the pamphlets that Martin published to accompany most of his major paintings, which often included a textual description and an outline engraving of the painting with a numerical key identifying its key figures and landmarks. Such pamphlets disclose Martin’s uncomfortable proximity to other forms of popular entertainment in early nineteenth-century Britain, for although pamphlets could be purchased at panoramas, dioramas, and other attractions, they were decidedly not a normal part of elite art exhibitions. In one copy of the pamphlet for his Deluge, Martin added a manuscript note about the scale of proportionality that governs the painting: “relative to the scale of proportion, viz. the figures and trees, the highest mountain will be found to be 15,000 Ft., the next in height 10,000 ft., and the middle-ground perpendicular rock 4,000 feet.”43 Although one was not included in the original pamphlet for Deluge, Martin published scalar keys to most of his major paintings.

Martin’s constant recourse to scale in his artworks was impugned by fellow artist Benjamin Robert Haydon, who in 1825 described Martin’s insistence upon assigning enormous and quantifiable measurements to objects in his paintings as “preposterous.”44 When, Haydon continued, Martin says of one of his pictures, “‘There, that horizon is twenty miles long, and therefore God’s leg must be sixteen relatively to the horizon,’ the artist really deserves as much pity as the poorest maniac in Bedlam.”45 It was an effect some regarded as too technical, too literal. But Martin’s repeated insistence upon the measurable quantification of his painted and printed world was also an invocation of the language of engineering.

An important clue as to why Martin would have repeatedly cited these scale effects can be found in the writing of another of Martin’s critics, Charles Lamb. Lamb complained that when looking at the original painting of Joshua it was difficult to perceptually disambiguate its figures. “Doubtless [at the original event] there were to be seen hill and dale, and chariots and horsemen, on open plain … but whose eyes would have been conscious of this array at the interposition of the synchronic miracle [of sun and moon together]? … the [viewer’s] eye may ‘dart through rank and file traverse’ for some minutes, before it shall discover, among his armed followers, which is Joshua!”46 Lamb accuses Martin of providing a surfeit of visual details. But more than this, he laments the lack of a clear compositional hierarchy or focal point. The eye is forced to wander across the surface of the painting without a clear sense of direction, without the proper pictorial infrastructure to direct the flow of the viewer’s perceptual attention. From this vantage point, we might say that sight itself was a flow in transit across the spatial surface of an artwork—and Lamb’s complaint was that it hadn’t been correctly managed or channeled. Such a diagnosis supplies a possible reason for why Martin later wanted to add a scalar key for Deluge: in the absence of all other forms of infrastructure, the viewer’s eye required an additional, extrapictorial scaffolding to guide it.

Martin’s great experiment was to supplant a traditional form of pictorial infrastructure, with its compositional arteries along which the eye is meant to travel, with a virtual one—scale. In the descriptive catalogue of his earlier painting of The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum (1822, Tate Britain), Martin supplies the following:

The scale of proportion may be observed by the figures on the beach, which is more than three hundred feet below the eye of the spectator; by tracing the figures along the Stabian way up to Pompeii will then supply the scale, the great Theatre being two hundred feet in width. An idea of the magnitude of the more remote objects may be formed form the buildings, trees, &c. The height of the crater is here represented four thousand feet above the level of the sea, allowance being made for the diminution it has sustained by the numerous subsequent eruptions. Its present height is computed to be from 3700 to 3900 feet.47

Martin identifies, as he did in many of his pamphlets, a human figure. On the basis of this, the viewer is invited to extrapolate other forms of dimensionality, some of which are extreme. Mobilizing this figure as a scalar key, the viewer can begin to imaginatively perceive increasingly large elements of the scene. The sheer length of the passage is itself instructive, for it suggests that the entire diegetic world of the painting can be apprehended on the basis of a scale whose underlying unit of measurement is a human figure. While scale is often understood as a form of relationality, here it serves as a kind of perceptual infrastructure—a metapictorial system through which experience could be appropriately managed.48 Martin’s scalar guides to his paintings structured the physical and imaginative space across which experience must transit.

To the extent that infrastructure strives to conceal or naturalize its visible presence, in Martin’s embankment plan, this operation is likewise applied to the material being circulated. In a literal sense, the flow of sewage would be hidden from view. But the diagram’s pictorial representation of sewage imagines that its unseemly materiality has also been converted into something homogeneous and translucent. The water of the Thames is nearly invisible, shown only as a bright blue wash and a pure white surface. This fantastical infrastructure is so successful that it’s completely sublimated the materiality of the flows it manages. The London of Martin’s diagram stands in direct contrast with the painted world of his Deluge, in which a lack of infrastructure coincides with a graphic rendering of pigmented material flows. Viscous swoops of paint materialize the catastrophic presence of unconstrained flows.

He may have been one of the most practically infrastructural artists of nineteenth-century Britain, but Martin’s work enables us to observe the extent to which infrastructure was a pervasive material and conceptual framework. Constable is another artist we might begin to understand differently if we recognize his work’s recurrent investment in forms of infrastructure. If it has been sub-visible to historians until recently, that should be taken as a reflection of its self-concealing protocols rather than evidence of its absence. With Martin, we encounter not only the built, “hard” infrastructure of transit, manufacturing, and resource extraction but also the immaterial systems that were guiding the circulation of information—and perhaps even perceptual experience itself. Infrastructure required artists to think in terms of systems, conduits, and flows. It was a distinctly nineteenth-century engine of possibility and of peril that shaped the world we have since inherited.

Notes

I am immensely grateful to Bridget Alsdorf and Marnin Young for the opportunity to contribute to this issue and to think alongside them. I thank Sam Rose and Luke Gartlan for their valuable suggestions about an earlier draft.

Although we rarely speak of the “infrastructure” of nineteenth-century British painting, historians have long been concerned with many of its core elements: the institutions through which artists trained and exhibited works, the social circuitry of patronage, the colonial and mercantile arteries through which art supplies were sourced from around the world, and the networks of printmakers and vendors through which printed reproductions were disseminated. One reason we don’t describe these elements as “infrastructure” is that the term would have been unrecognizable to those involved. The word didn’t emerge until the late nineteenth century and wasn’t commonly used until the early twentieth century.1 To speak of the “infrastructure” of nineteenth-century British painting nonetheless allows certain features to surface more clearly for us now: the physical scaffolding that facilitated the circulations of artists and artworks among a whole host of related human and nonhuman things, as well as the embeddedness of this infrastructure itself within multiple interacting systems. It can be narrowly defined in terms of the “hard” infrastructure of physical systems, described by Brian Larkin as the “built networks that facilitate the flow of goods, people, or ideas.”2 But “soft” infrastructure can also designate immaterial networks, as in another definition offered by Larkin: “things and also the relation between things.”3 We might therefore glimpse hard infrastructure in the painted canal system of John Constable’s The Lock (fig. 1), while also recognizing the soft infrastructure of the institution (the Royal Academy) through which that painting was exhibited and sold. Infrastructure even transformed the luminous contours of Constable’s world: the streets, shops, and theaters around the Royal Academy were increasingly lit by gas lamps supplied with gas through extensive networks of underground pipes.4

Infrastructural technologies—particularly associated with steam-powered transit and manufacturing—enabled the colonial expansion, urbanization, and industrialization we now regard as synonymous with the emergence of “modernity” in nineteenth-century Britain. While art historians have often remarked upon the conditions of industrialization in Western Europe and particularly the reorganization of labor and class, infrastructure names an essential but underrecognized component of that transformation. As indicated by the prefix infra—“below” in Latin—infrastructure typically lies beneath the visible surface. Even when it is visually present it is designed to evade our conscious attention.5 This article takes seriously the logic of infrastructure as both a material feature of nineteenth-century British modernity and as a conceptual framework that aspires to the frictionless transit of materials, people, information, and economic value across space. The accelerating circulation of information, of images, and of commodities across Europe and its colonial networks required various forms of physical scaffolding which dictated the parameters of how things could circulate.6 Media histories have been exceptionally alert to this dynamic.7 Inspired by such work, by research in environmental history, and by recent scholarship on contemporary art, might the idea of infrastructure permit us to apprehend a broader dynamic developing at this moment?8 Did the nineteenth century bring with it new possibilities for what it could mean for an artist to work and to think infrastructurally?

To sketch out some of the forms this may have taken, I focus on one of the most literally infrastructural artists of the nineteenth century, John Martin. Best known for his spectacular historical landscapes and popular mezzotints, Martin was also a prolific amateur engineer. In many regards, Martin was an atypical artist: never admitted to the Royal Academy, he enjoyed periods of intense public popularity but was also criticized for pandering to middle-class tastes.9 His epic paintings of destruction coupled intense atmospheric effects with the careful rendering of precisely measured architectural formations—a conjunction that left his artworks somewhere between the sublime and the actuarial.10 Yet Martin was also intensely “of his time.” His obsessive historicism—his extensive and laborious efforts to recreate ancient settings with mathematical exactitude in his artworks—gave pictorial form to a broader Victorian popular interest in the past.11 Foregrounding the infrastructural components of Martin’s work enables us to think differently about both Martin and his contemporary moment.

Because they concern physical systems for circulating people and materials, Martin’s engineering projects supply unusually compressed examples of an infrastructural way of thinking about and picturing the world in the early nineteenth century. But infrastructure, I argue, entails more than this. I take infrastructure to designate a characteristically modern understanding of space in terms of the managed circulation of material and immaterial forces. The concept operates in tandem with the economic imperatives of extractive capitalism. Extraction “names,” in the words of Nathan Hensley, “not just a material practice but an … orientation toward the world … based on use.”12 It is an epistemology of instrumentalization and disposability that requires the physical circulation of people and commodities as well as the metaphorical circulation of economic value. By excavating the infrastructural “stakes” of Martin’s work, we also encounter the metabolic disturbances that were being confronted by an industrializing and carbonizing Britain.

In what follows I revisit three aspects of Martin’s work: his artistic printmaking, his engineering projects, and his large-scale oil paintings. Across them, we can recognize Martin’s modernity as a function of his ability to conceptualize the world in terms of flows and the infrastructure that manages those flows. It included but was not limited to pictorial representations of physical infrastructure. Precisely because infrastructure strives to conceal its operations, I pursue alternative ways we might recognize its presence and in doing so come to apprehend its centrality for early nineteenth-century British art.

Mezzotint Flows

In 1827, Martin produced a mezzotint and etched print (fig. 2) of his first truly successful oil painting, Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still (1816, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Like many of his compositions, Joshua contrasts a detailed rendering of an Old Testament architectural setting with a churning swell of natural and supernatural forces that encircle the scene. Martin’s recently completed mezzotint series illustrating John Milton’s Paradise Lost earned him both critical and financial success. Critics who found his large-scale spectacular oil paintings vulgar or garish were more approving of the prints, which had simplified compositions and fewer architectural details. “When reduced to the mere black and white of mezzotint prints,” one reviewer observed in 1829, the “power of his designs” were “undiminished if not indeed increased.”13 John Ruskin later captured the view of many when he remarked that Martin’s “chief sublimity consists in lamp-black,” referring to the sooty pigment which dominated the mezzotint compositions.14

Joshua is a print that hinges on the drama of circulation. In the center of the composition stands the eponymous leader of the Israelite forces, Joshua, who has been defending the city of Gibeon from attack. On the right, Gibeon’s monumental architecture is illuminated from above by bleaching sunshine. On the left, the dense accumulation of clouds over the receding landscape signals the divine storm of hail and fire that will be brought upon the Amorites as they flee. Martin pictures the moment when Joshua appeals to God to halt the movement of the sun and prolong the solar day, giving him more time to defeat the Amorite forces. When rendered in the limited tonalities of mezzotint, the composition sets the ominous power of divine darkness seen on the left against the creative extrusion of supernatural daylight shown on the right. In other words, this is a narrative in which a human protagonist has endeavored to disrupt the natural cycle of day and night for his own advantage.

Rather than look to the lucid repetition of modular architectural units, I take the infrastructural interest of this print to ultimately reside in its narrative and compositional investment in managing powerful flows. It is the convergence of atmospheric, luminous, and military forces upon the Amorites that will guarantee Joshua’s success. The upper perimeter of the print is dominated by the directional movement of atmospheric forces toward the retreating Amorites. A dense procession of Israelite soldiers spills into the right foreground from Gibeon in pursuit, channeled along a narrow built road. These flows have been activated by Joshua, who further directs the circulation of the planets themselves, albeit through a divine intermediary. Joshua’s appeal to prolong the day takes on particular intensity in the context of a rapidly carbonizing British economy, in which steam-powered combustion was creating a form of labor power that was not constrained by alternating diurnal periods of work and nocturnal periods of rest.15 The radiant intensity of artificially extended daylight seen drenching the city of Gideon likewise recalls the luminous operations of steam-powered blast furnaces used widely in Britain for iron production since the late eighteenth century. These effects were installing themselves in central London, too, through the extension of coal-powered gas lighting on the streets. (“Not a dark corner to be got for love or money,” complains a man in Thomas Rowlandson’s 1802 caricature of the new gas lights at Pall Mall.) Industrial metaphorics aside, the print bespeaks an investment in the conditions of multiple, interacting modes of circulation—and a sense that civilizational survival coincides with and depends upon controlling those modes.

Martin was more attentive than most artists of his stature to the physical systems and material flows through which a print came into being. Spurred by his successful prints of the late 1820s, Martin built a workshop below his studio where he personally engraved and produced impressions of several of his large mezzotints, experimented extensively with new printmaking techniques, and supervised the assistants who printed the rest of his output. His print studio, I am suggesting, is one site where we might begin to trace Martin’s investment in devising physical systems for enabling and directing circulation. As his son Leopold later described it, the workshop contained: “fly-wheel and screw presses of the latest construction; ink grinders, glass and iron; closets for paper; French, India, and English drawers for canvas, blankets, inks, whiting, leather shaves, &c.; out-door cupboards for charcoal and ashes ….”16 This was a complex setting designed by Martin which comprised large devices operated by rotaries and shafts, industrial products such as iron, and industrial by-products such as ash. Although he was hardly the first artist to maintain his own print studio, Martin’s attentiveness to the technical specifications and physical systems through which prints come into being resonates with a broader set of preoccupations in his artwork and his engineering projects.

Martin was particularly known for pioneering mezzotint on large steel plates, which were more difficult to engrave than copper but proved much more durable in the printmaking process. For Joshua, “a large steel plate was procured from Harris and Co.” which was first given a mezzotint ground upon which etching was then done.17 Steel engraving itself was still a relatively new technique that had been introduced in Britain less than a decade earlier. Martin’s great innovation was to employ it for mezzotint and to do so on a physically significant scale—his print of Belshazzar’s Feast from 1826 was the first large-scale soft mezzotint of an artwork. As described by Leopold, Martin would distribute varying mixtures of oils and inks on the plate between each pull as he worked the mezzotint up to its finished state: “at the outset he would pull a plain proof of the plate, using ordinary ink; then work or mix the various inks. First, he made a stiff mixture in ink and oil; secondly, one with oil and less ink; and thirdly, a thick mixture of both ink and oil.”18 The repeated pull of intermediate states was typical of the mezzotint process. What this description highlights, though, is that Martin’s print studio was a space for employing novel technologies and industrial materials in a manner that was newly possible in the early nineteenth century. Martin sourced steel, oils, and charcoal. For example, lamp black, the source of Martin’s “chief sublimity” according to Ruskin, was an ink typically pigmented with chimney soot. It was a cheap form of industrial waste. Martin’s printmaking entailed guiding the interaction of soot and steel, directing how one moves across the surface of the other. Not unlike Joshua himself, Martin managed the distribution of light and dark in his workshop—he could direct the flows of pigmented darkness, draw out fields of luminosity, and when he was satisfied with a given apportioning of light and dark, he could halt the process and affix it to paper.

The Infrastructural Metropolis

Printmaking was also an arena in which Martin envisaged large-scale interventions in the built environment that would create dedicated areas of light and darkness, that would channel viscous flows, and that would facilitate the transit of waste, people, goods, and economic value. The same year that he produced his mezzotint of Joshua he published the first of many engineering plans, which would eventually include a railway circuit linking London’s rail terminals, a coastal lighting scheme for ship navigation, and numerous systems for managing London’s water supply and sewage. As many have noted, Martin grew up outside of Newcastle and was exposed at an early age to coal pits, lead mines, and glassworks.19 Although he received no formal training as an engineer, his brother William published nearly 150 technical plans and inventions and even won a medal in 1813 for his design for a spring weighing machine.20 Martin counted among his friends J.K. Brunel, engineer of the Great Western Railways, and the inventor Charles Wheatstone, whose early experiments with the electric telegraph were witnessed by Martin.21

Martin’s own invention for a mine safety lamp exemplifies his investment in the labor conditions of industrializing Britain and more specifically his ability to conceptualize a dynamic field of desirable and undesirable flows which require physical structures to manage (fig. 3). The print shows Martin’s lamp on the left and the famous Davy-lamp on the right for comparison. Mining explosions were known to be caused by the accumulation of “fire damp,” a form of highly flammable methane released by coalbeds. When a concentration of these gasses came into contact with the lamp flames needed to illuminate the dark mine shafts, they triggered large-scale, deadly explosions. Martin’s lamp design disaggregates the desired in-flow of oxygen to feed the lamp’s flame from the undesired ingress of flammable firedamp. The ventilation system at the top of the lamp likewise permits the outflow of the gases released by the flame without enabling firedamp to enter.

In reality, Martin’s plan was unsuccessful: both he and his brother submitted designs for mining safety lamps that were tested for the Committee on Accidents in Mines. When his lamp exploded, Martin immediately withdrew it from consideration.22 Nonetheless the lamp enacts, on a small scale, what I have been suggesting we term an infrastructural form of thought predicated on managing the flows set in motion by modern industry. Here, too, Joshua comes to emblematize the place of the human within such a configuration—firstly in his role guiding natural and atmospheric movements, and secondly in his pursuit of prolonging or augmenting conditions of illumination. The mine shaft was a site in which Martin sought to maintain distinct spaces of light and darkness, not unlike the work undertaken in his print studio. Indeed, the sooty by-product of oil lamps (including the one designed by Martin himself) was precisely what was used to make black ink for printmaking. Illumination within the mine created the material conditions for the picturing of darkness within the print.

A similar logic was employed in the design of large-scale mining ventilation, which envisioned the unidirectional channeling of air currents. Martin would have been introduced to this subject by his brother William, whose mine ventilation systems and engines John produced illustrations for.23 Martin would go on to publish a plan for mining ventilation in addition to the design for a safety lamp, later testifying for the government’s Select Committee on Accidents in Mines in 1835. The logic is concisely captured in one of the early plans published by John Buddle in 1814 (fig. 4). (Buddle, a proponent of the Davy lamp, repeatedly disagreed with the Martin brothers about some of their rival designs. However, the general principles of mining ventilation and safety were undisputed.) The circular opening designates a partitioned vertical shaft through which air was drawn down into the mine and later expelled upwards. Routed along two linear itineraries in the depths of the mine that are plotted out in dotted lines, fresh air was guided by wooden air-doors, designated in the print by shaded double lines, and would eventually re-enter the vertical shaft—typically fitted with a furnace beneath it to propel the air back up to the surface. Airflow was just one kind of circulation upon which coal mining relied; elaborate transit networks both within the mine and at the surface used interlinked systems of pulleys, pumps, and small railways to transport miners, working materials, water, and extracted coal. In short, like many of the growing industries of early nineteenth-century Britain, mining relied upon multi-level systems for managing the movement of both visible and invisible entities. It further required the measured interaction of surface and subsurface worlds.

Mining ventilation systems, located deep beneath the earth’s surface, typified the self-concealing operations of nineteenth-century infrastructure. However, infrastructure did sometimes entail highly visible interventions into the built surface of the physical environment. Prominent metropolitan building projects included the construction of New London Bridge beginning in 1824, the steady extension of railway lines, gas-powered street lighting that quickly spread across central London from 1807 onwards, and the transformation of London’s docks from 1802 to 1828, to say nothing of the major urban planning projects underway in the growing cities of Edinburgh, Liverpool, Glasgow, Newcastle, and elsewhere.24 One of the half-dozen docks that were built during this period, the West India Docks of 1800 exemplify the imbrication of modern transit infrastructure with colonial commerce: with imports on the right and exports on the left, these two docks enabled Britain’s trade in sugar, tobacco, cotton, and other valuable commodities produced through enslaved labor in the Caribbean (fig. 5). Daniell’s aquatint emphasizes the rational linearity of the scene, with bright and uniform warehouses bordering each dock. The reflective light blue surface of the Thames evokes the fantasy not only of an immaculate urban waterway but also the ease of smooth transit across the physical itineraries of the empire and the metaphorical space of the marketplace. A print like this serves as a vivid reminder that images we tend to classify as “British landscapes” were often characterized by and took as their subject matter the built infrastructure of a modernizing capitalist economy predicated on the extraction and circulation of resources across colonial networks. To move through the urban spaces of London entailed locating oneself within enormous multi-level systems for managing the movement of people, commodities, energy sources, and waste.

William Heath’s famous series March of Intellect captured some of the sinister aspects of this configuration (fig. 6). Like Daniell, he portrayed a physical environment that was dominated by transit systems. Heath likewise evokes a sense of intimacy between London and its colonies, although here it is disorienting and threatening rather than orderly and pristine. A telescopic metal tube in the center of the composition offers transit via the “Grand Vacuum Tube Company” from London “direct to Bengal.” A monstrous bat-like creature flying overhead carries convicts to New South Wales in colonial Australia. On a distant hillside, figures are shot into the air out of a cannon that advertises itself as a “quick conveyance for the Irish emigrant.” Unlike the Daniell print or the Buddle mine ventilation diagram, Heath summons a nightmarish vision in which new forms of transit have collapsed the geographical distances of Britain’s empire. More importantly, their movement is not guided along discrete linear vectors; several of Heath’s fantastical modern forms of transit appear to be on the verge of crashing into one another, to say nothing of the Irish immigrants who are literally falling from the sky. This is a scene of metropolitan Britain whose infrastructure is failing to properly manage the circulation of people and forces.

What the Heath and Daniell prints ultimately share is an experience of emergent modernity characterized not by industrialization in a generic sense but by the practical and aesthetic presence of infrastructure—infrastructure in the narrower sense of built systems for enabling and managing the movement of commodities, people, energy, waste, and other materials. It is from this vantage point that I propose we revisit John Martin’s engineering projects, and specifically just one of his plans for improving London’s supply of drinking water and its disposal of human waste. Although some of Martin’s designs incorporated railways and docks, it was with the water and waste infrastructure of London that Martin primarily occupied himself, eventually attempting to form multiple failed joint-stock companies to enact his plans.25

Martin and Metabolic Rift

Controversies over London’s water and waste infrastructure were mounting in the first two decades of the nineteenth century. Domestic sewage was typically collected in cesspits, where it would be periodically emptied by “nightmen” who transported the waste by wagon. It would be sold to farmers and their intermediaries where the waste could be repurposed as valuable manure. The agricultural produce whose growth was supported by manure would later be transported back into the city and consumed as food, where it would presumably be converted into waste once more. Although some forms of this urban-rural exchange persisted into the early twentieth century, it declined drastically in the early nineteenth century as Britain’s cities began producing much more waste than was needed by farms. The advent of flush toilets and the rise of more effective fertilizers (initially bonemeal and later superphosphates and imported nitrogen-rich guano) precipitated the near-total collapse of the market for urban nightsoil by the middle of the century.26 Instead, British industrial agriculture became increasingly dependent upon imported fertilizers that disrupted the nutrient cycle which had formerly sustained the long-term fertility of the soil. In the mid-nineteenth century, the German chemist Justus von Leibig even characterized this depletionary model of British agriculture as a form of theft.27

The disruption of a self-sustaining system in which urban manure supported rural agriculture was later held up by Karl Marx as a paradigmatic example of the destructive effects of capitalism on the relationship between human laborers and the natural world. In a famous passage in Capital, Marx writes that “capitalist production … disturbs the metabolic interaction between man and the earth, i.e. it prevents the return to the soil of its constituent elements consumed by man in the form of food and clothing; hence it hinders the operation of the eternal natural condition for the lasting fertility of the soil.”28 In place of a metabolic system of material exchange with the soil, the human encounters material estrangement from the environment. John Bellamy Foster evocatively termed the development a “metabolic rift.”29 This names a broader category within Marxist and now environmental thought in which self-renewing systems of exchange between human activity and the natural world are catastrophically terminated.30 In the case of London’s waste infrastructure crisis, the existing soil nutrient cycle was derailed, the pursuit of ever-greater agricultural productivity intensified soil degradation, and the accumulation of waste in urban centers produced an ancillary form of pollution: sewage was increasingly directed into the Thames, which was also one of the primary sources of water for portions of the city. (Of course, the formerly metabolic system of urban-rural manure exchange had its problems too—among other things, it propagated the spread of deadly diseases.)

Martin spent roughly two decades publishing a series of plans for improving the water supply and waste management of London (whose history has been most extensively documented and discussed by Lars Kokkonen).31 At various points this included filtering sewage out of the Thames and transporting it via boat to the countryside; sourcing additional water from the Colne river; creating new public urban baths, fountains, and waterfalls; the building of new water towers, aqueducts, and centralized sewage repositories; and a range of designs to prevent sewage from entering the Thames in the first place. Martin’s first plan, published in 1827, was almost certainly inspired by the publication of an incendiary pamphlet that accused the Grand Junction Waterworks Company of sourcing their water just meters from one of the Thames’s large open sewers. The Dolphin; or, Grand Junction Nuisance characterized the water as “offensive to the sight, disgusting to the imagination, and destructive to health.”32 The frontispiece portrayed the company’s in-take pipe in the center, which it described as a “wooden-headed, dingy-coloured, ill-shapen, insidious engine of destruction” (fig. 7).33 To the right, the company’s buildings include a steam-powered pump that draws the water up into its system while also releasing large quantities of smoke onto the grounds of the neighboring Chelsea Hospital shown to the left of the Dolphin. The frontispiece animates the contrasting architectural styles of Sir Christopher Wren’s late seventeenth-century design for the hospital with the plain buildings and tall smokestack of the Grand Junction, although previous water-supply companies had operated on the site as well. The Grand Junction Waterworks Company was among five companies that had held a monopoly on the supply of drinking water to London since 1817, and which the pamphlet blamed for the degradation of its quality. Its water, the pamphlet alleged, was “saturated with the impurities of fifty thousand houses—a dilute solution of animal and vegetable substances in a state of putrefaction.”34 The resulting scandal triggered the creation of a Royal Commission which published a report criticizing the quality of London’s water in 1828. Among the material discussed in this report was a plan from John Martin to create an aqueduct sourcing water from the Colne.35

Martin’s infrastructural ambition for London is best glimpsed in a plan published a decade after the first Royal Commission report (fig. 8). He ultimately came to advocate for the complete embankment of the Thames, which would contain two sewers running parallel to the river, wharves for loading and unloading goods, and a grand public walkway. Although his designs were never realized, the subsequent embankment of the Thames overseen by Joseph Bazalgette in the second half of the century included many elements that were originally proposed by Martin. I am not the first to observe certain common features across Martin’s engineering drawings and his artworks—his preferred use of monumental architectural colonnades in both was commented on even by some of his contemporaries.36 Rather than identify visual homologies between, for example, the Joshua mezzotint (fig. 2) and this proposal for embanking the Thames (fig. 8), I propose that we recognize in them an especially infrastructural way of understanding the lived conditions of emergent nineteenth-century British modernity, characterized by human efforts to manage the powerful and potentially dangerous forces circulating around them.

Martin’s embankment print proposes dedicated circuits through which each kind of flow can be channeled, with an emphasis on discrete conduits of unidirectional circulation and the disaggregation of desired and undesired materials. It is a logic that surfaces in his plans for mining lamps, for example, and which likewise finds expression in the systems of mining ventilation that Buddle and his contemporaries were promoting (fig. 4). Although Martin was unusually attuned to the conditions of circulation, he was hardly unique. Like the West India Docks celebrated in the print by Daniell, Martin’s vision for London is a terrain of inflows and outflows, of systems for facilitating the activities of commerce and industrial manufacturing, and of structures that promote the value-generating transit of people and goods.

The embankment print also shares, albeit indirectly, in some of the material dynamics of the mezzotint process in which the artist was so invested. Recall that the metal plate is first roughened all over with a rocker that creates tiny pits that hold ink. The printmaker then smooths portions of the surface back down to create fields of light. Put differently, the dark “ground” of the mezzotint plate in its initial state is an interactive field in which above and below are not stable and distinct positionalities. They instead comprise a single, variegated field. It is the task of the printmaker to restore or reassert a distinction between the surface of the plate and its depths, to create new planar barriers through which pictorial legibility becomes possible. The embankment plan likewise insists upon a new division between the surface and subsurface worlds. It envisions stone expanses that will impose smoothness and uniformity on a formerly varied field, that will enforce the separability of desires and undesired flows. A material terrain of disorderly interactions is segregated into portions of darkness and portions of light.

Martin’s engineering plans for London were responsive to the negative conditions of metabolic rift, although he would have found little common ideological ground with Marx. Not only did Martin endeavor to improve the operation of Britain’s capitalist industries but he was also an explicitly commercially minded artist. Martin himself proclaimed a “strong interest … in the improvement of the condition of the people, and the sanatory state of the country,” which is likewise borne out in his designs to improve the working conditions of coal miners.37 But as Kokkonen has shown, Martin’s plans for the water and waste infrastructure of London were motivated by a desire to “prevent economic waste to the nation,” rather than by a particular concern for pollution or for the soil cycle.38 In spite of this, Martin’s plans did prioritize restoring metabolic properties to British agriculture, going to great lengths to design systems by which urban manure could once again become a cost-effective fertilizer for rural farmers. In one version of his Thames embankment plan, he proposed redirecting the air pressure produced by sewage ventilation to manufactories along the river, another mechanism for recuperating at least partial metabolic exchange between the generation of waste and its productive repurposing.39

Technological infrastructure enabled the conditions of metabolic rift: for example, by making possible the growth of cities, by enabling the transit of food across vast distances, and by intervening into traditional cycles of waste and re-use. It was also called upon to manage the harmful consequences of metabolic rift—for example, through the creation of an enormous multi-level system for disaggregating the inflow of water and the outflow of sewage in London. Although he may have held little in common with Marxist ideology, Martin appears to have been more alert than most to the negative disruption of a system of urban-rural exchange, more anxious than most about failing to harness the latent economic value of waste, and more motivated than most to see in infrastructure the potential for compensatory systems.

The Infrastructure of Experience

Of the many monumental scenes of catastrophe that Martin painted, it is in his Deluge of 1834 that his infrastructural anxieties are most acute—all the more so because the painting omits the elaborate colonnades and finely-rendered architectural settings that have been formerly identified as a point of contact between his engineering interests and his artworks (fig. 9).40 As I have already suggested, an artist can picture things in infrastructural terms without portraying the literal subject matter of infrastructure. We might equally seek out in formal, material, narrative, or even perceptual terms a notion of physical space that is characterized by powerful flows and by human efforts to manage those flows. It requires thinking in terms of systems of circulation and exchange. It both creates and attempts to compensate for the metabolic disruptions of industrial capitalism. Martin embraced industrial capitalism, but he also seems to have been aware that the powerful forces it set into motion required careful management.

The Deluge evokes the failure of infrastructure on a civilization-ending scale. The sole form of transit that will preserve human and animal life, Noah’s Ark, is almost impossible to see, perched atop one of the rocky ledges in the distance. It is perceptually and narratively inaccessible to the viewer. The only space to which the viewer has access is a narrow bluff around which a number of life-terminating forces gather: lightning, boulders, and churning water. The rest of the scene is marked by the absence of systems for managing flows and channeling circulations. That which is meant to be located below (namely, water) swells up above the human figures in the center of the composition. That which is meant to be located far above (for example, the rocky substrate of the mountain on the right) is now tumbling down. It is an environment that is structurally contrasted with the scene invoked in the London embankment print, in which the secure positionalities of above and below are rendered in linear clarity.