When we look at a painting or photograph, or read a poem or novel, how relevant are authorial intentions?1 I’m going to agree (strongly) with Walter Benn Michaels that we need to keep caring about these intentions, and also that we need to do so in a sophisticated way. Michaels and I will part company only when it comes to the details. Should our new, sophisticated theory really be Anscombian, or is there a way to make sense of artworks while still preserving our ordinary understandings of intentional action?2

What I’ll suggest is that the latter is indeed possible, as long as we keep in place a set of important distinctions: between generic intentions and specific intentions; between empirical painters and postulated artists; and between intention at time of conception and intention at time of display. If we hang on to those, I think we can solve the problems Michaels rightly wants to tackle—even, perhaps, at a lower conceptual cost.

I

Let’s start from the relevance of intention to the understanding and appreciation of artworks. This is a notoriously vexed and difficult question, but Michaels marshals an excellent set of arguments, both here and in his other writings, for taking intention into account. (“The Shape of the Signifier” should be required reading, in my opinion, for all students of literature.3) I may be reading between the lines, but I take one of Michaels’s thoughts to be that intention is already essential at the moment when we decide that something is an artwork, even before we decide what, more specifically, it’s up to.4

One fun example: in 2004, a bag of trash was found on the floor at Tate Britain, and the janitor threw it away. It turned out, unfortunately, to be part of a million-dollar artwork, Gustav Metzger’s “Recreation of the First Public Demonstration of Auto-Destructive Art.”5 So what’s the difference between part of an artwork and a pile of garbage left on the floor in a museum? Intention. Superficially, the two are identical (“indiscernible,” in Danto’s sense6); but the presence of intention gives one of them an altered effect, a new significance. Trash functions differently when it’s deliberately placed on the floor of a museum, because of what we imagine the artist is trying to do by putting it there. (Michaels might not like this Warholesque example, but I actually think it goes in his general direction.)

So even what looks like a mere description—calling something an “artwork,” not a “bag of trash”—is swimming in intentionality. Something similar is on view in a lovely experiment conducted by Paul Bloom and Susan Gelman.7 You take a given object (say, a crudely-fashioned box) and show it to a small child, explaining how it came into existence. In one condition, you tell the child it was deliberately fashioned: “Elizabeth had a piece of cardboard. She carefully cut it out with scissors. Then she folded it and glued it together. This is what it looked like.” In the other condition, you tell the child it was a matter of happenstance: “Elizabeth had a piece of cardboard. She accidentally left it on the floor. When she came back to get it, her cat had been scratching on it. This is what it looked like.” In the first condition, five-year-olds are much more likely to call the result a box. In the second condition, five-year-olds are much more likely to call the result a piece of cardboard. Two identical objects receive different descriptions from kids the same age, merely because of perceived intentionality.

The same is true at a more granular level of specificity. Is A Modest Proposal a serious suggestion that people should eat babies or a biting piece of satire? Is Plan 9 From Outer Space a hilarious failure or, like The Evil Dead, a brilliant joke? Those decisions, which we often make without realizing it, are decisions about intention. (Verbal irony always implies an author.) Or again: have you ever found yourself saying “oops” when you saw a boom microphone straying onto camera? “Oops” means that someone messed up, which means that they failed to do what they meant to, which means that, again, you’re assuming intentions whether you think you are or not. And did you feel “wow” when you looked at the Sistine Chapel ceiling? The experience of awe in response to virtuosity is another place where we’re thinking about artists, however much we take ourselves to agree with Roland Barthes.8

In addition, as Michaels brilliantly demonstrates, artworks can even draw on questions of intentionality, thematize them, be about them.9 They can make process more or less visible; they can play with the complexities and raise difficult questions for us to answer. Winogrand’s photographs, Michaels shows, are about the difference between a mere document and a work of art—very similar to the difference between a mere piece of cardboard and a box. Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation, to take a different example, features a character called Charlie Kaufman trying to make a movie about flowers but ending up making a movie about himself, Charlie Kaufman, trying to make a movie. How would a “death of the author” type even begin to understand this film?

II

So I think we can safely rule out the extreme anti-intentionalist position, according to which intention either doesn’t or shouldn’t make any difference to how we experience art. But what about photography?10 Ought we to agree with Susan Sontag that since much of what’s in a photo was not put there by the photographer, “photographs don’t seem deeply beholden to the intentions of an artist”?11 No; here again Michaels is surely right. He’s right to say both that intention matters in photography and that photography raises the question of intentionality in a peculiarly sharp way. While some features of the image (such as framing and camera angle) are generally intended, and correctly read as intended, other features (such as how many people happened to surround the Pope at a particular moment) are generally beyond the photographer’s control. For the ideal painting, there would be a good answer to every “why this?” question, in terms of the artist’s project. For even a great photograph, the answer to “why this?” is sometimes going to be “it just happened that way.”

Still, do we need Anscombe in order to head off misguided readings, whether from those who think intention is always irrelevant or from those who think photography is nothing special? I’m not convinced that we do. It seems to me that we can get everything Michaels wants while still holding onto a more everyday (or Davidsonian) understanding of intention.12 On this understanding, there really is a difference between arm-raising and arm-rising (between me calling for attention, say, and the wind blowing my hand up into the air). That difference is my intention to lift my arm, understood as a combination of beliefs and desires. I have a desire to do something (say, indicate to my teacher that I’d like to speak) and a belief about how best to accomplish it (say, by raising my arm). My intention is at once a cause of the action, a reason for the action, and part of the explanation for the action. (“Why did that doofus Landy raise his hand?” “Probably has another idiotic thing to say.”)

Michaels appears to resist this way of thinking about things. He writes, paraphrasing Anscombe, that “neither your intention nor anything else makes a bodily movement [like arm-rising] into an act [like arm-raising].”13 Elsewhere he seems, at least prima facie, to endorse a refusal of the question about the difference between arm-raising and arm-rising.14 And he blames Wimsatt and Beardsley for thinking of intention as a cause.15 Now it may well be that Michaels’s way of understanding intention can work; but I suspect the Davidsonian approach will too, as long as we bear two vital distinctions in mind.

III

The first distinction we need is between the empirical maker and the postulated artist. (What follows is a wretchedly brief summary of Alexander Nehamas’s indispensable essay, “The Postulated Author.”16 In the context of literary works, Nehamas distinguishes between empirical writer and postulated author; I’m tweaking the terms a little to allow for a better fit with visual arts.) Garry Winogrand the maker was the flesh-and-blood human being who lived from 1928 to 1984, briefly joined the air force, was married three times, had three kids, breathed, ate, and slept. Winogrand the artist, by contrast, is the being we imagine as we look at his photographs. That Winogrand is a creature in our head—nothing more nor less than the agent who might have willed all the effects produced by the work.

The word “might” is crucial here. The postulated author—a close cousin of Wayne Booth’s “implied author”—is simply the result we get when we try to assign all the different effects of a text to a single cause, the name we give to the overarching impact produced by the work as a whole. In constructing this figure in our head, we aren’t figuring out what the real-life maker actually wanted; we’re figuring out what she could (and maybe should, ideally) have wanted. The postulated artist, in Nehamas’s sense, is the agent who might, with singular purpose, have willed all the effects produced by the work. She is a plausible variant of the maker: our Winogrand postulate can’t be an ancient Greek philosopher or medieval monarch. But for the most part she is formed on the basis of the work(s) in front of us.

That’s handy, because in many important cases we don’t know anything at all about the maker. (Who wrote Lazarillo de Tormes? Who was—or who were—Homer?) In a second set of cases the maker isn’t talking, or is talking dismissively. (I’m looking at you, Sam Beckett.) And in a third set of cases, the maker is better at making art than at explaining it. Given such concerns, our artist figure had better not be identical to the maker.

Now that we have the postulated artist in place, we can make a second distinction, between two possible moments at which we might situate that artist’s intention. We might think the relevant intention is the one she has before ever setting pen to paper, brush to canvas, or finger to shutter. (Let’s call that a conception-intention.) Or we might think the relevant intention is the one she has when everything is finished and she’s decided to send the artwork out into the world. (Let’s call that a display-intention.) At this second point, our postulated artist might well have some reasonably elaborate, wide-ranging, and worked-out ideas about what the piece could accomplish: moving the viewer to tears, making her laugh, raising questions about intention, defamiliarizing the everyday… And those ideas might intersect in substantial ways with her reasons for considering the artwork (a) finished and (b) worthy of display. For all of that to be the case, there’s absolutely no need for her to have formed any of her plans from the get-go; every single one of them could have emerged along the way. The relevant intentions are the one she has at the end of the creative process.17

The thought above runs counter to what I take to be an assumption of Michaels, who appears to imply that if intention is understood as a mental state, it can only be understood as a state taking place before creation: “once you understand the artist’s intention as the mental state that gets added to the physical fact of the work (the thought you have while taking your picture), you can’t help but start to wonder why it should make any privileged difference to the work’s meaning”; “part of the interest of the photograph is that it runs the risk of reducing the artist’s intention to… what you’re thinking while you take the picture.”18 (My emphasis in both cases.) Michaels is right, it seems to me, to have serious doubts about basing a theory on what’s in the mind of a photographer before she clicks the shutter. But that leaves open what’s in her mind when she chose a negative, printed it, and sent it out for display. And here, suddenly, Winogrand’s 300,000 unprinted negatives suddenly gain a new importance. Winogrand didn’t just take one photograph each time; he took many. Later on, he carefully chose which to print and which to discard. So what we’re interpreting, when we interpret a Winogrand, is his decision to show us this particular image. Because he knew it “worked.”19

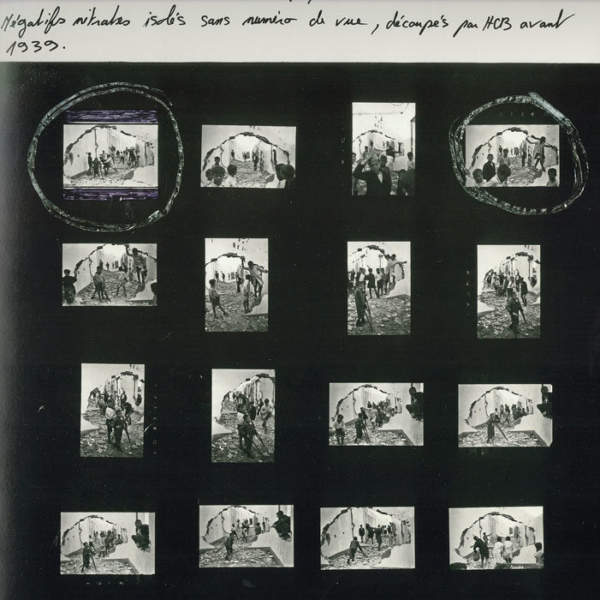

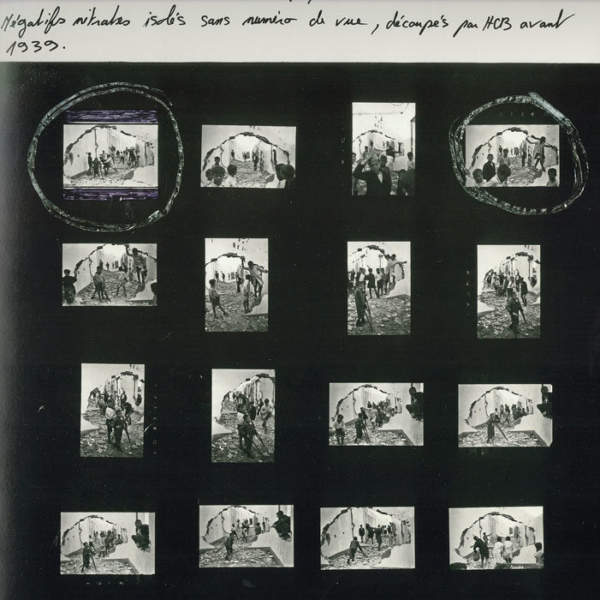

We now have a decent way, as I see it, to understand Cartier-Bresson’s “Cardinal Pacelli” photograph (1938), in which, as Michaels brilliantly notices, there’s a “kind of rhyme between [two] bald men looking down.”20 Cartier-Bresson didn’t tell those two men to go bald, to attend the event, or to stand facing in the same direction. But that doesn’t mean intention (in the everyday sense) isn’t relevant. Cartier-Bresson didn’t control the movement of heads, but he did control the release of the image. He could have chosen a different image on his contact sheet—or he could simply have chosen not to display a picture of the Pope at all. We don’t ask, as we would with a painted canvas, “why are there two bald heads here?”21 (Again, Michaels is excellent on the painting-photography distinction.) But we do ask “why did Cartier-Bresson choose the shot with the two bald heads?” There is still an intention working causally; it’s just a postulated display-intention, not an empirical conception-intention.

Interestingly, Michaels appears to use very similar language when discussing the photo: “Why shouldn’t we think instead that the kind of rhyme between the two (actually three) bald men looking down was part of what made the photograph work for Cartier-Bresson?” (Compare something Michaels says about Winogrand: “this photograph can only have the right effect on us if we understand what Winogrand was trying to do.” Emphasis mine.)”23 Michaels approvingly quotes Cavell as dismissing the idea of “some internal, prior mental event causally connected with outward effects”24—but that’s exactly what we see here, it seems to me. “Part of what made the photograph work for Cartier-Bresson” is a reference to an internal mental event. The mental event is prior—prior, at least, to display, albeit not prior to shutter-clicking. And the internal, prior mental event is causally connected with outward effects, in as much as there would be no outward effects without the decision to develop the photo and show it in an exhibition.

My proposal, then, is that we interpret artworks in the light of intention, that magic feature that turns cardboard into a box, A Modest Proposal into something cunning, and a bag of trash into part of an installation. But that intention is a display-intention. When it comes to generic aims, such as “making a work of art,” we could perhaps make do, in many cases, with conception-intentions; but when it comes to specific projects, like that of raising questions about agency or the aesthetic, display-intentions are going to be indispensable. Further, the display-intention is that of the postulated artist, not that of the empirical maker. The intention remains a cause of the action, a reason for the action, and part of the explanation for the action—it’s just the intention of a postulate once the shutter-clicking is over, not the intention of a flesh-and-blood person before raising the camera. And there’s still a difference between arm-raising and arm-rising (in this case, between the “Cardinal Pacelli” made by Cartier-Bresson and a “Cardinal Pacelli” made by a spill in a chemical factory). To solve the problems Michaels rightly identifies—to keep intention at the heart of interpretation, including of photography; to preserve the unusual situation of photography in this regard; to rule out theories based on conception; to see Winogrand as worrying, through his images, about how to make them come across as what they are—we don’t have to become Anscombians. We just need to be display-intention Nehamasians.

I’ve read this little essay over many times now, and I think I’m ready to send it into the world. It’s far from perfect, and it certainly isn’t what I thought it was going to be when I started. But for good or ill, I think it’s my intention now that counts. Or the postulated me does, at least.

When we look at a painting or photograph, or read a poem or novel, how relevant are authorial intentions?1 I’m going to agree (strongly) with Walter Benn Michaels that we need to keep caring about these intentions, and also that we need to do so in a sophisticated way. Michaels and I will part company only when it comes to the details. Should our new, sophisticated theory really be Anscombian, or is there a way to make sense of artworks while still preserving our ordinary understandings of intentional action?2

What I’ll suggest is that the latter is indeed possible, as long as we keep in place a set of important distinctions: between generic intentions and specific intentions; between empirical painters and postulated artists; and between intention at time of conception and intention at time of display. If we hang on to those, I think we can solve the problems Michaels rightly wants to tackle—even, perhaps, at a lower conceptual cost.

I

Let’s start from the relevance of intention to the understanding and appreciation of artworks. This is a notoriously vexed and difficult question, but Michaels marshals an excellent set of arguments, both here and in his other writings, for taking intention into account. (“The Shape of the Signifier” should be required reading, in my opinion, for all students of literature.3) I may be reading between the lines, but I take one of Michaels’s thoughts to be that intention is already essential at the moment when we decide that something is an artwork, even before we decide what, more specifically, it’s up to.4

One fun example: in 2004, a bag of trash was found on the floor at Tate Britain, and the janitor threw it away. It turned out, unfortunately, to be part of a million-dollar artwork, Gustav Metzger’s “Recreation of the First Public Demonstration of Auto-Destructive Art.”5 So what’s the difference between part of an artwork and a pile of garbage left on the floor in a museum? Intention. Superficially, the two are identical (“indiscernible,” in Danto’s sense6); but the presence of intention gives one of them an altered effect, a new significance. Trash functions differently when it’s deliberately placed on the floor of a museum, because of what we imagine the artist is trying to do by putting it there. (Michaels might not like this Warholesque example, but I actually think it goes in his general direction.)

So even what looks like a mere description—calling something an “artwork,” not a “bag of trash”—is swimming in intentionality. Something similar is on view in a lovely experiment conducted by Paul Bloom and Susan Gelman.7 You take a given object (say, a crudely-fashioned box) and show it to a small child, explaining how it came into existence. In one condition, you tell the child it was deliberately fashioned: “Elizabeth had a piece of cardboard. She carefully cut it out with scissors. Then she folded it and glued it together. This is what it looked like.” In the other condition, you tell the child it was a matter of happenstance: “Elizabeth had a piece of cardboard. She accidentally left it on the floor. When she came back to get it, her cat had been scratching on it. This is what it looked like.” In the first condition, five-year-olds are much more likely to call the result a box. In the second condition, five-year-olds are much more likely to call the result a piece of cardboard. Two identical objects receive different descriptions from kids the same age, merely because of perceived intentionality.

The same is true at a more granular level of specificity. Is A Modest Proposal a serious suggestion that people should eat babies or a biting piece of satire? Is Plan 9 From Outer Space a hilarious failure or, like The Evil Dead, a brilliant joke? Those decisions, which we often make without realizing it, are decisions about intention. (Verbal irony always implies an author.) Or again: have you ever found yourself saying “oops” when you saw a boom microphone straying onto camera? “Oops” means that someone messed up, which means that they failed to do what they meant to, which means that, again, you’re assuming intentions whether you think you are or not. And did you feel “wow” when you looked at the Sistine Chapel ceiling? The experience of awe in response to virtuosity is another place where we’re thinking about artists, however much we take ourselves to agree with Roland Barthes.8

In addition, as Michaels brilliantly demonstrates, artworks can even draw on questions of intentionality, thematize them, be about them.9 They can make process more or less visible; they can play with the complexities and raise difficult questions for us to answer. Winogrand’s photographs, Michaels shows, are about the difference between a mere document and a work of art—very similar to the difference between a mere piece of cardboard and a box. Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation, to take a different example, features a character called Charlie Kaufman trying to make a movie about flowers but ending up making a movie about himself, Charlie Kaufman, trying to make a movie. How would a “death of the author” type even begin to understand this film?

II

So I think we can safely rule out the extreme anti-intentionalist position, according to which intention either doesn’t or shouldn’t make any difference to how we experience art. But what about photography?10 Ought we to agree with Susan Sontag that since much of what’s in a photo was not put there by the photographer, “photographs don’t seem deeply beholden to the intentions of an artist”?11 No; here again Michaels is surely right. He’s right to say both that intention matters in photography and that photography raises the question of intentionality in a peculiarly sharp way. While some features of the image (such as framing and camera angle) are generally intended, and correctly read as intended, other features (such as how many people happened to surround the Pope at a particular moment) are generally beyond the photographer’s control. For the ideal painting, there would be a good answer to every “why this?” question, in terms of the artist’s project. For even a great photograph, the answer to “why this?” is sometimes going to be “it just happened that way.”

Still, do we need Anscombe in order to head off misguided readings, whether from those who think intention is always irrelevant or from those who think photography is nothing special? I’m not convinced that we do. It seems to me that we can get everything Michaels wants while still holding onto a more everyday (or Davidsonian) understanding of intention.12 On this understanding, there really is a difference between arm-raising and arm-rising (between me calling for attention, say, and the wind blowing my hand up into the air). That difference is my intention to lift my arm, understood as a combination of beliefs and desires. I have a desire to do something (say, indicate to my teacher that I’d like to speak) and a belief about how best to accomplish it (say, by raising my arm). My intention is at once a cause of the action, a reason for the action, and part of the explanation for the action. (“Why did that doofus Landy raise his hand?” “Probably has another idiotic thing to say.”)

Michaels appears to resist this way of thinking about things. He writes, paraphrasing Anscombe, that “neither your intention nor anything else makes a bodily movement [like arm-rising] into an act [like arm-raising].”13 Elsewhere he seems, at least prima facie, to endorse a refusal of the question about the difference between arm-raising and arm-rising.14 And he blames Wimsatt and Beardsley for thinking of intention as a cause.15 Now it may well be that Michaels’s way of understanding intention can work; but I suspect the Davidsonian approach will too, as long as we bear two vital distinctions in mind.

III

The first distinction we need is between the empirical maker and the postulated artist. (What follows is a wretchedly brief summary of Alexander Nehamas’s indispensable essay, “The Postulated Author.”16 In the context of literary works, Nehamas distinguishes between empirical writer and postulated author; I’m tweaking the terms a little to allow for a better fit with visual arts.) Garry Winogrand the maker was the flesh-and-blood human being who lived from 1928 to 1984, briefly joined the air force, was married three times, had three kids, breathed, ate, and slept. Winogrand the artist, by contrast, is the being we imagine as we look at his photographs. That Winogrand is a creature in our head—nothing more nor less than the agent who might have willed all the effects produced by the work.

The word “might” is crucial here. The postulated author—a close cousin of Wayne Booth’s “implied author”—is simply the result we get when we try to assign all the different effects of a text to a single cause, the name we give to the overarching impact produced by the work as a whole. In constructing this figure in our head, we aren’t figuring out what the real-life maker actually wanted; we’re figuring out what she could (and maybe should, ideally) have wanted. The postulated artist, in Nehamas’s sense, is the agent who might, with singular purpose, have willed all the effects produced by the work. She is a plausible variant of the maker: our Winogrand postulate can’t be an ancient Greek philosopher or medieval monarch. But for the most part she is formed on the basis of the work(s) in front of us.

That’s handy, because in many important cases we don’t know anything at all about the maker. (Who wrote Lazarillo de Tormes? Who was—or who were—Homer?) In a second set of cases the maker isn’t talking, or is talking dismissively. (I’m looking at you, Sam Beckett.) And in a third set of cases, the maker is better at making art than at explaining it. Given such concerns, our artist figure had better not be identical to the maker.

Now that we have the postulated artist in place, we can make a second distinction, between two possible moments at which we might situate that artist’s intention. We might think the relevant intention is the one she has before ever setting pen to paper, brush to canvas, or finger to shutter. (Let’s call that a conception-intention.) Or we might think the relevant intention is the one she has when everything is finished and she’s decided to send the artwork out into the world. (Let’s call that a display-intention.) At this second point, our postulated artist might well have some reasonably elaborate, wide-ranging, and worked-out ideas about what the piece could accomplish: moving the viewer to tears, making her laugh, raising questions about intention, defamiliarizing the everyday… And those ideas might intersect in substantial ways with her reasons for considering the artwork (a) finished and (b) worthy of display. For all of that to be the case, there’s absolutely no need for her to have formed any of her plans from the get-go; every single one of them could have emerged along the way. The relevant intentions are the one she has at the end of the creative process.17

The thought above runs counter to what I take to be an assumption of Michaels, who appears to imply that if intention is understood as a mental state, it can only be understood as a state taking place before creation: “once you understand the artist’s intention as the mental state that gets added to the physical fact of the work (the thought you have while taking your picture), you can’t help but start to wonder why it should make any privileged difference to the work’s meaning”; “part of the interest of the photograph is that it runs the risk of reducing the artist’s intention to… what you’re thinking while you take the picture.”18 (My emphasis in both cases.) Michaels is right, it seems to me, to have serious doubts about basing a theory on what’s in the mind of a photographer before she clicks the shutter. But that leaves open what’s in her mind when she chose a negative, printed it, and sent it out for display. And here, suddenly, Winogrand’s 300,000 unprinted negatives suddenly gain a new importance. Winogrand didn’t just take one photograph each time; he took many. Later on, he carefully chose which to print and which to discard. So what we’re interpreting, when we interpret a Winogrand, is his decision to show us this particular image. Because he knew it “worked.”19

We now have a decent way, as I see it, to understand Cartier-Bresson’s “Cardinal Pacelli” photograph (1938), in which, as Michaels brilliantly notices, there’s a “kind of rhyme between [two] bald men looking down.”20 Cartier-Bresson didn’t tell those two men to go bald, to attend the event, or to stand facing in the same direction. But that doesn’t mean intention (in the everyday sense) isn’t relevant. Cartier-Bresson didn’t control the movement of heads, but he did control the release of the image. He could have chosen a different image on his contact sheet—or he could simply have chosen not to display a picture of the Pope at all. We don’t ask, as we would with a painted canvas, “why are there two bald heads here?”21 (Again, Michaels is excellent on the painting-photography distinction.) But we do ask “why did Cartier-Bresson choose the shot with the two bald heads?” There is still an intention working causally; it’s just a postulated display-intention, not an empirical conception-intention.

Interestingly, Michaels appears to use very similar language when discussing the photo: “Why shouldn’t we think instead that the kind of rhyme between the two (actually three) bald men looking down was part of what made the photograph work for Cartier-Bresson?” (Compare something Michaels says about Winogrand: “this photograph can only have the right effect on us if we understand what Winogrand was trying to do.” Emphasis mine.)”23 Michaels approvingly quotes Cavell as dismissing the idea of “some internal, prior mental event causally connected with outward effects”24—but that’s exactly what we see here, it seems to me. “Part of what made the photograph work for Cartier-Bresson” is a reference to an internal mental event. The mental event is prior—prior, at least, to display, albeit not prior to shutter-clicking. And the internal, prior mental event is causally connected with outward effects, in as much as there would be no outward effects without the decision to develop the photo and show it in an exhibition.

My proposal, then, is that we interpret artworks in the light of intention, that magic feature that turns cardboard into a box, A Modest Proposal into something cunning, and a bag of trash into part of an installation. But that intention is a display-intention. When it comes to generic aims, such as “making a work of art,” we could perhaps make do, in many cases, with conception-intentions; but when it comes to specific projects, like that of raising questions about agency or the aesthetic, display-intentions are going to be indispensable. Further, the display-intention is that of the postulated artist, not that of the empirical maker. The intention remains a cause of the action, a reason for the action, and part of the explanation for the action—it’s just the intention of a postulate once the shutter-clicking is over, not the intention of a flesh-and-blood person before raising the camera. And there’s still a difference between arm-raising and arm-rising (in this case, between the “Cardinal Pacelli” made by Cartier-Bresson and a “Cardinal Pacelli” made by a spill in a chemical factory). To solve the problems Michaels rightly identifies—to keep intention at the heart of interpretation, including of photography; to preserve the unusual situation of photography in this regard; to rule out theories based on conception; to see Winogrand as worrying, through his images, about how to make them come across as what they are—we don’t have to become Anscombians. We just need to be display-intention Nehamasians.

I’ve read this little essay over many times now, and I think I’m ready to send it into the world. It’s far from perfect, and it certainly isn’t what I thought it was going to be when I started. But for good or ill, I think it’s my intention now that counts. Or the postulated me does, at least.