1.

The room is perhaps the fundamental element of any architecture. As a primitive hut, a simple shelter, a cave or a retreat, the room commands a unique and unrepeatable definition of a place. Making room means to clear a space for oneself: to identify a limit between inside and outside (room, from the proto-Indoeuropean root reue-“to open, space”).

Like organs in a body, specific arrangements of rooms correspond to species of buildings with distinctive characteristics. Despite its concatenations, a room always preserves the possibility of autonomy, as a stand-alone entity. In the Western classical tradition—from Vitruvius to Alberti and Palladio—rooms are usually categorized according to forms accurately proportioned to their fulfilled functions.

Within an imaginary catalog of rooms, the cell could be considered its contradictory expression. In opposition to the functional determinacy of the room, the nature of the cell is, in fact, ambiguous. A cell always implies its subordination to a larger whole, either considered as the hidden core of a temple (cell, from the Indoeuropean root kel-“to cover, conceal, save”), a storage room, or a more ordinary a small chamber. Its confined dimensions suggest the idea of being protected within a mass, contained in a sequence, or held in rhythm.

The cell speaks through the language of tissues and membranes rather than organs, referring to the whole body as its minute constituent atom. As a unit that could be repeated, it is inherently collective. Whereas the room can be indifferent to its surroundings, a cell is always deduced from the assembling logic of which it is part of. In this regard, it is not a coincidence that the use of cells characterizes particular collective buildings such as housing blocks, barracks, hospitals, schools, prisons, monasteries, and other institutions; all of which are based on compliance to a set of imposed measures.

A cellular organization constitutes the fundamental trait of any disciplinary regime. Cells compartmentalize space, minimize gestures, enclose bodies, and amplify control. In Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault remarks the relation between cell and confinement within the panopticon prison: “They are like so many cages, so many small theatres, in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible….He is seen, but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject in communication.” 1

For Foucault, the panopticon was a paradigmatic architecture: the spatial expression of a much wider social machine, the one that progressively instituted a disciplinary ensemble of norms and crimes, surveillance and punishment as a distinctive way of exerting power. The prison building, in this sense, was the formalization of a different composition of forces: a technology that already existed in the past but became relevant when a new sensibility in the art of punishment emerges in parallel to the evolution of penal law in the 18th century. In other words, the cell is a neutral architectural element that becomes extremely effective when innervated by specific power relations and inserted within a disciplinary diagram.

Not by chance, in his analyses of Bentham’s Panopticon, Foucault explains how similar architectures previously worked under different regimes of power and how the origin of the panoptic cellular segmentation was first experimented in Christian monasteries, where spaces for individual meditation and reclusion were juxtaposed next to collective facilities.2 Paraphrasing Robin Evans, the Panopticon stripped the soul out of the Christian monastery and made good use of its carcass, turning the anchorite’s voluntary withdrawal from the moral contamination of the world into the forced reclusion and permanent control over the prisoners.3

From here, the cell inherited many of the negative connotations we now hold of it: as the simple minimum space for survival, or the restrictive entity subjected to the authority and rigorous control of an external architectural apparatus. Yet, it would be a mistake to interpret the cell solely as an instrument of control and coercion. By reversing this perspective, the cell could instead be regarded as the constituent spatial module to imagine new forms of collective living. As a vessel to consciously limit and negotiate individuality within the broader societal domain, the cell might also help to discover how to live together through mutual acquaintance and construction of habits in common.

Solitary life does not connote a system of rules. For the isolated individual there is no problem of confrontation or negotiation, and hence no problem of form. Form only arises through the encounter and the negotiation of limits between different entities. The collective formulation of a rule coincides with the cellular concatenation.

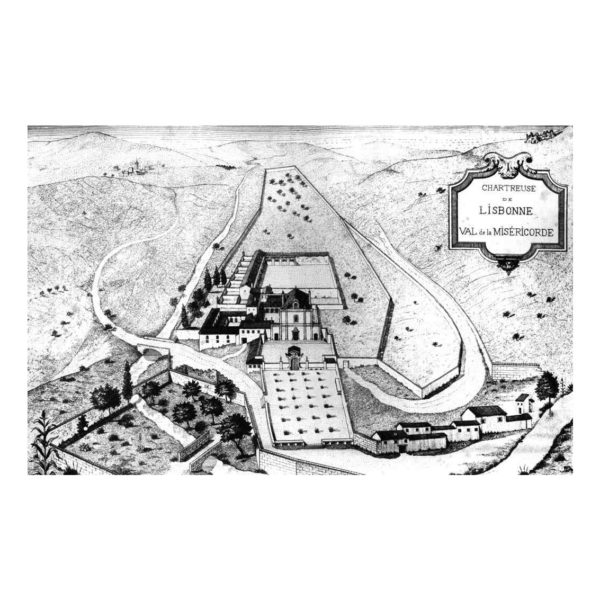

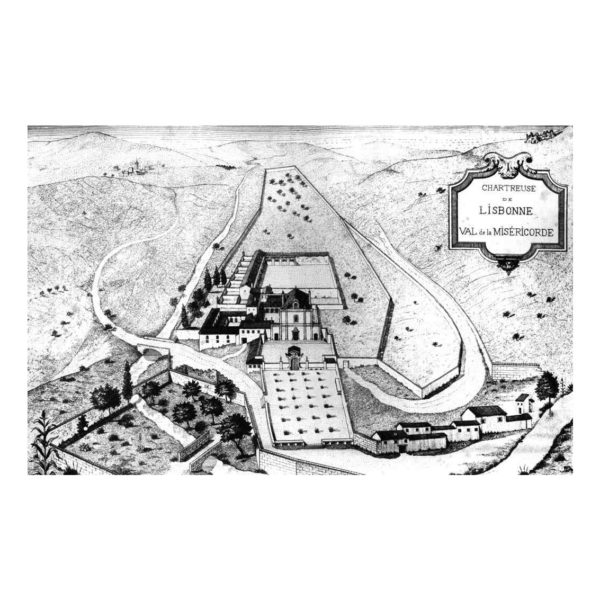

The Cartuxa de Laveiras of Lisbon is, in this sense, paradigmatic. Established as a Carthusian monastery—where monks lived in permanent isolation from society within their cells—and later converted into a correctional center—where groups of teenagers were subjected to the order of the reformatory and lived within large dormitories fabricated from the destruction of the original monks’ cells—the Cartuxa demonstrates the alternative possibilities of an architecture of first chosen, and later imposed rules. More than a solitary retreat, or an assigned amount of inhabitable square meters, the cell was the instrument to refine a way of living that was collectively ordered, but individually enacted.

As the Carthusians would conceive it, the cell is a mental condition: a desert. The cell conceptually formalizes the desert where Jesus wandered fasting for forty days, fighting against evil temptations. Its constrained space embraces the vast extensions of a journey, which is “long, and the way dry and barren, that must be traveled to attain the fount of water, the land of promise.”4

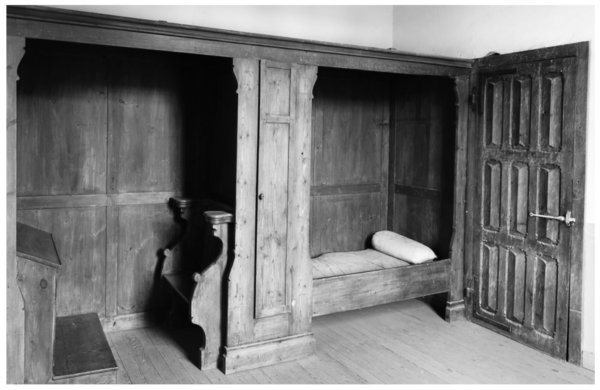

Following the founder of the Carthusian Order’s aspirations, St. Bruno, the cell provides a space of solitude in which a form of life can be conducted under constant thought, without distractions and away from temptations. In the cell nothing is superfluous: every single object, space or ritual performed is necessary to the Carthusian monk for her journey of awakening. Life sediments within a constellation of firm points—a cubiculum for sleeping and a prie-dieu for praying, a table and a chair, the workshop, a garden with a porch—which becomes progressively more intense through constant repetition.

Such an extreme form of estrangement could be perhaps considered a valid paradigm especially in our contemporary condition. Living in a society that continually demands of us to exhibit, document, and share every single performed activity, a critical distance can steer us away from the apparatuses indexing out existences, our curated profiles and codified identities. Carthusian asceticism thus turns into a lesson of productive rationalism: an antidote against collective hypnosis, social bonds, constructed farces and imposed behaviors.

In the Genealogy of Morals, Friedrich Nietzsche redefines the notion of asceticism, not as a denial of existence or a withdrawal from society, but rather an affirmation of existence, a way to penetrate life in its most profound depths and to exalt the human potential. Zarathustra would abandon his retreat and descend from the mountains to the villages predicating a return to the earth and the body. The etymology of the word “asceticism”—from the Greek verb askein—indicates a form of exercising and training or, in other words, a way to rationally control the self, to administer its capacities and intensify the will to power.

Along the same trajectory, Max Weber distinguished an “outer-worldly asceticism,” entirely projected towards a complete detachment from mundane temptations, characterized by mysticism and hermetic contemplation, from an “inner-worldly asceticism” which instead demands a complete devotion to mundane activities. Weber finds the origin of this immanent form of asceticism in the Protestant concept of the “calling,” according to which the highest form of moral obligation for the individuals was to fulfill their duties in the society. In this way, labor becomes an absolute end in itself, a form of vocation and responsibility: a way of worshiping God through one’s worldly affairs.5

To Weber, the celebration of labor, crafts, and daily life activities celebrated by the Protestant ethics, revealed the emergence of new spiritual drive aimed at gaining profit for its own sake in the pursuit of a “calling:” the spirit of Capitalism.6 “The person who lives as a worldly ascetic is a rationalist”—Weber writes—“not only in the sense that he rationally systematizes his conduct but also in his rejection of everything that is ethically irrational, esthetic, or dependent upon his emotional reactions to the world and its institutions. The distinctive goal always remains the alert, methodical control of one’s pattern of life and behavior. This type of inner-worldly asceticism included, above all, ascetic Protestantism, which taught the principle of loyal fulfillment of obligations within the framework of the world as the sole method of proving religious merit, though its several branches demonstrated this tenet with varying degrees of consistency.”7

Such a mundane asceticism turns rationalism into an operative tool for increasing efficacy and control over daily actions. The austere space of the cell, minutely calculated to fulfill domestic necessities and rituals, becomes a testing ground to transform the mystic contemplation of monks into the immanent search for awareness of the alienated soul. Whereas the disciplinary regime subordinates the cell into a machine of constrictions, the inner-worldly asceticism transforms the cell into an instrument of emancipation and estrangement from the overwhelming spectacle of society in our everyday individual acts.

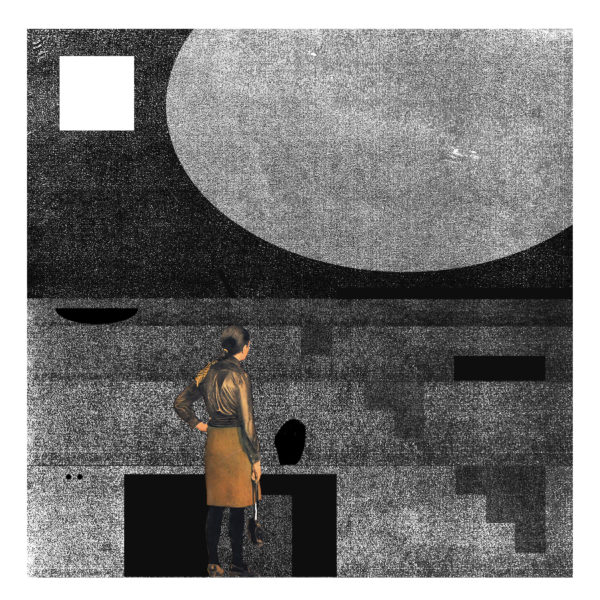

A Certain Kind of Life explores the typology of the Carthusian monastery as an architecture of absolute rationality, wherein the form of life cannot be detached from the space and rituals of the liturgy the monastery shelters. Drawing from nine centuries of monastic architecture, the project reconsiders asceticism as a way to meditate upon present living and working conditions: a necessary estrangement to look closely at reality, its daily gestures and rituals.

In a society wherein maximum integration generates maximum alienation, a rudimentary practice of asceticism offers both a strategy of resistance and an antidote against collective hypnosis, social bonds, and constructed farces and behaviors. The asceticism that A Certain Kind of Life advocates is a form of productive rationalism, to conduct life under constant thought by dispelling anxieties of endless competition, consumerism, and the consequential illusions of promise.

Taking place at the Cartuxa de Laveiras as an associated project of the 2019 Lisbon Architecture Triennale, A Certain Kind of Life proposes three interventions: a Cell for a Certain Individual, an architectural evocation of worldly asceticism; an Atlas detailing the charterhouse type in exemplary reiterations; and Deserts, an exhibition of prototypes for contemporary living, which distill the rationalism of daily rituals into architectural forms through specific procedures in space.

2.

From the solitary fugues of St. Antoninus or St. Paul in the Egyptian desert to the earliest experiments of isolated communities in Thebaid, Palestine, Judea, Syria, and North Africa between the third and fourth centuries, two primary forms of monasticism developed within the history of Christianity: the eremitic, corresponding to the solitary retreat from the world in remote hermitages, and the cenobitic, or the collective attempt to live together in isolation according to an established rule, confined within an architectural enclosure.

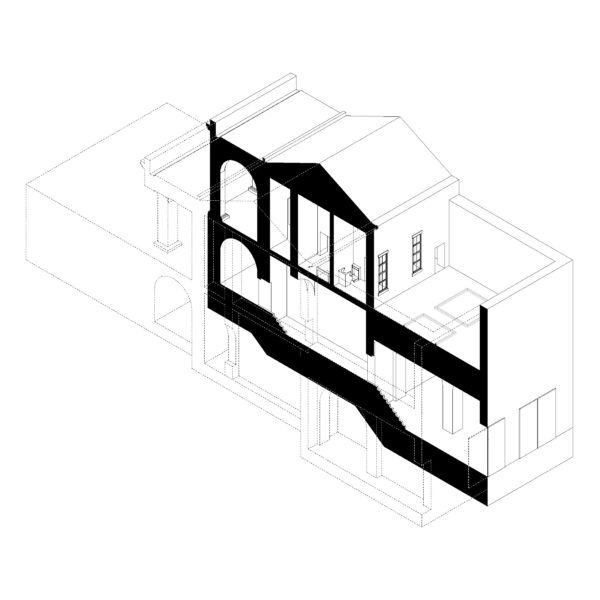

The Carthusian monastery, or charterhouse, offers a spatial combination of both of these forms of living: an architecture that inseparably connects the individual and collective dimensions through the sheer rationality of its spaces and the specificity of its observed principles. The charterhouse strictly separates the living quarters of the monks from the church, the chapter, the workshops, and the gathering halls, combining the various rhythms of the single inhabitants into a collective soul. Both a spiritual and physical form, the charterhouse has persisted since its foundation by St. Bruno in 1084.

Nothing could be added or taken away from its layout. In the charterhouse, nothing is owned, but everything is used. Every spatial aspect is defined by the requirements of liturgy performed: the highest spirituality is attained through the strictest definition of its silent ritual, resonating everywhere in the cloisters, objects, clothes, food, chants, gestures, and activities. When visiting the Charterhouse of Ema near Florence in 1910, Le Corbusier praised its respectful and harmonic combination of privacy and commonality, through which the individual and the collective juxtapose without merging, as in an idiorrhythmic ensemble. It was from this combination that he conjectured his 1922 project for the Immeubles-villas.

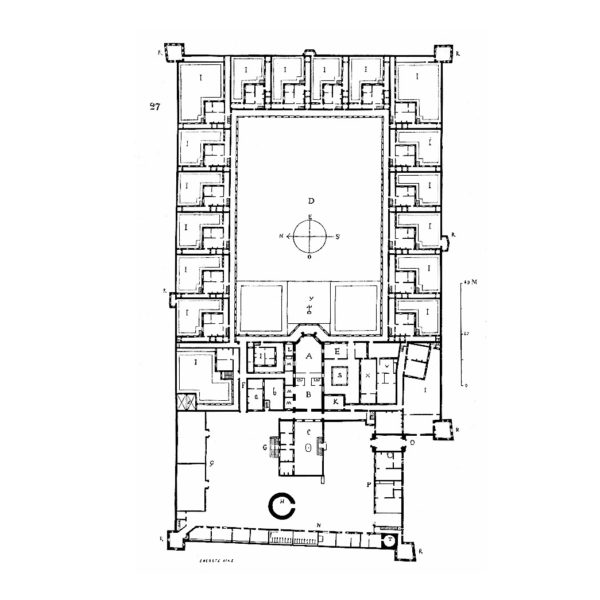

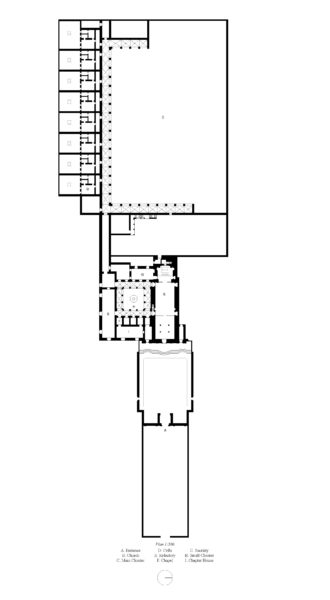

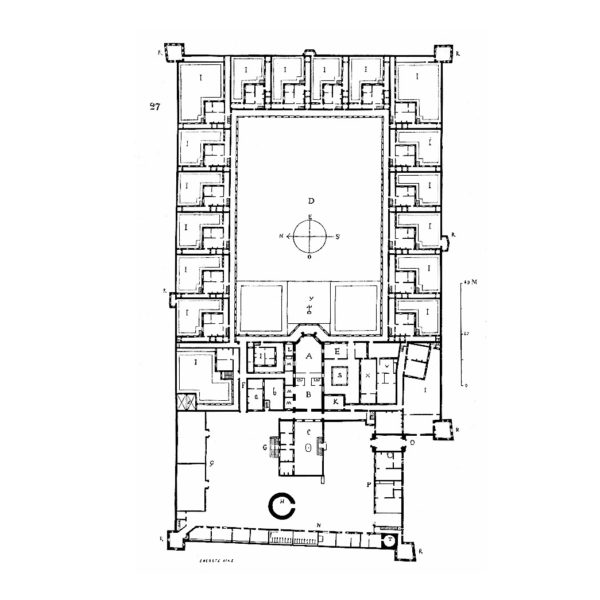

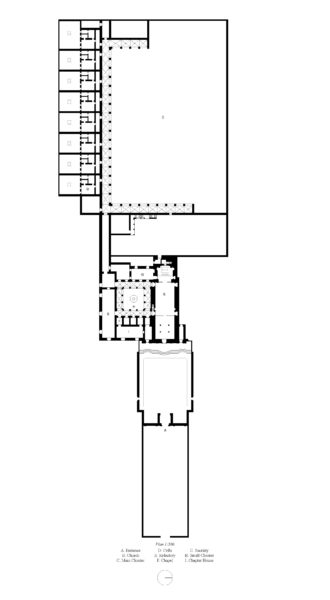

The plan of the Charterhouse is generally organized into three parts: the cells of the monks surrounding a large cloister; a buffer zone with collective programs such as church, chapter house, and refectory, where the daily officia and occasional events are held in common; and a public interface comprising productive facilities, services, and gathering areas—wherein a group of laymen and converse brothers live and interact with the external world, helping the Carthusian monks to preserve their autonomy from society. This part of the charterhouse adapts to the topography and specific contextual conditions, producing unique differences within the assemblage.

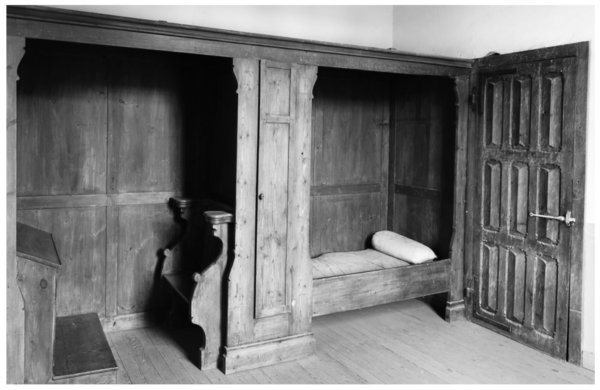

Each monk’s cell, or desert, provides necessary equipment for simple living: a bed, a prie-dieu, a table for studying or eating, a lavatory, a workshop, an ambulatory for recreation, and a garden. The liturgy is what prescribes the life of the monks: it is the form-giver to their activities performed in silence and contemplation. Every single action—praying, reading, studying, working, eating, or resting—is performed in a specific space and inscribed in the plan of the cell and its equipment. From midnight to the afternoon, a series of silent collective gatherings harmonically intersects with the individual rituals in the cell.

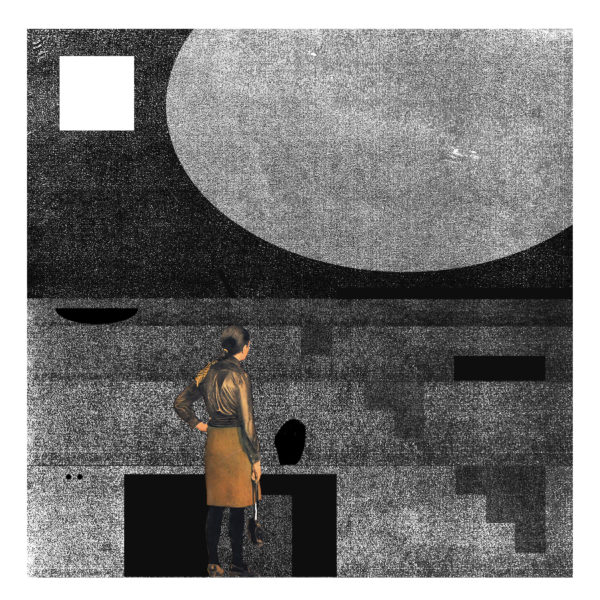

The Cell for a Certain Individual reinterprets the Carthusian monk’s desert as a refuge from the congestion and the hectic rhythms of society. The asceticism of the cell is neither an escape nor a voluntary exodus from the world, but, on the contrary, a total immersion in it: a way to rediscover and reinvent ourselves, rendering the world at a sharper resolution. In this way, the cell turns into a mirror, a window to look at ourselves and critically reframe our daily rhythms and chores.

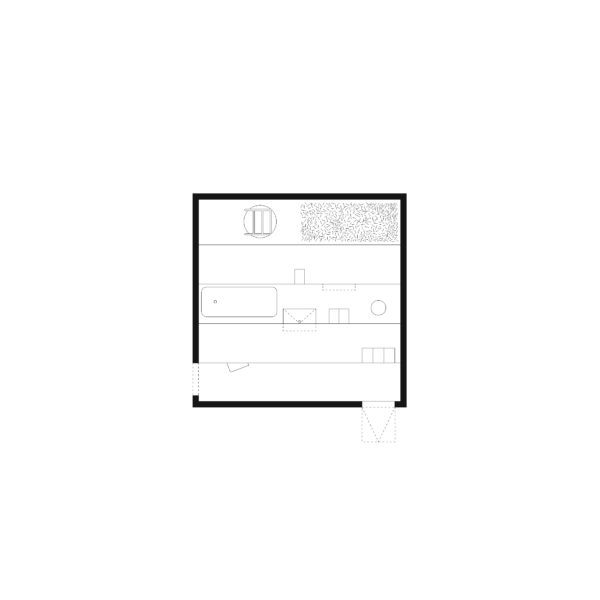

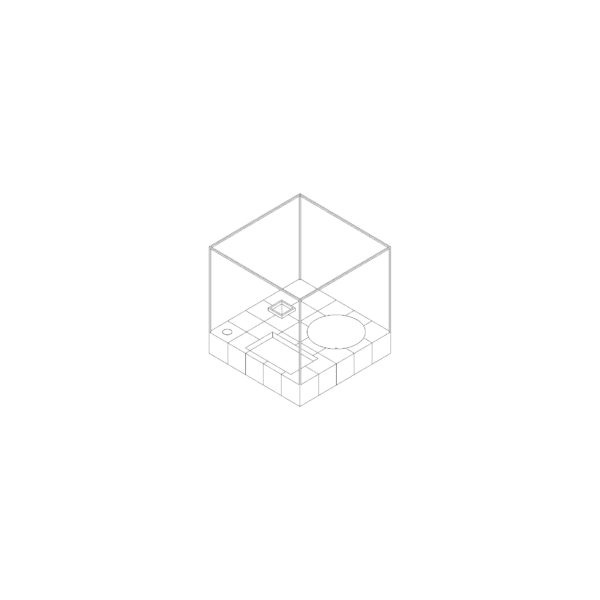

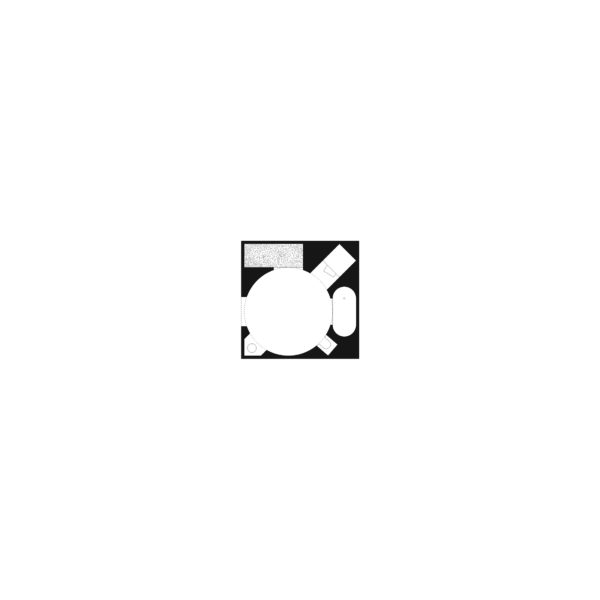

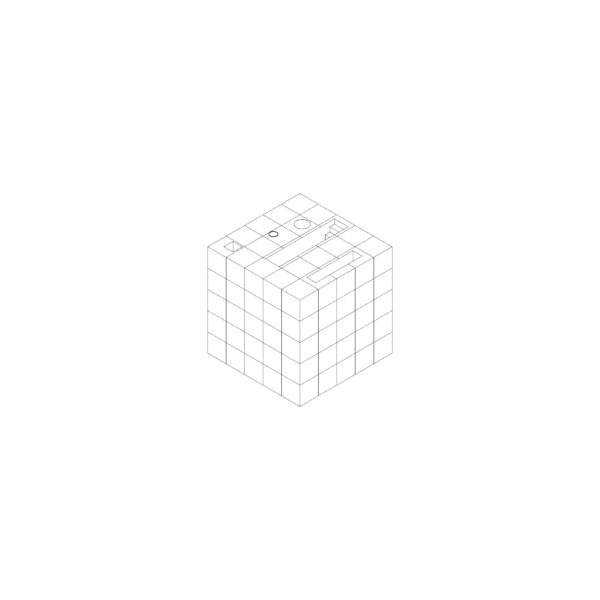

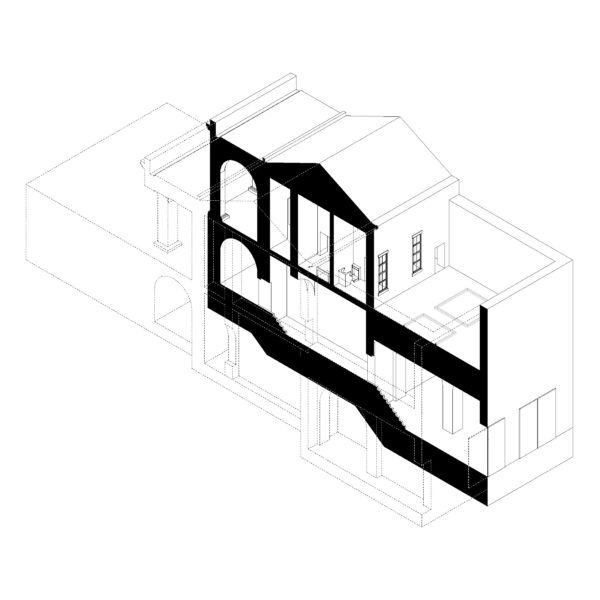

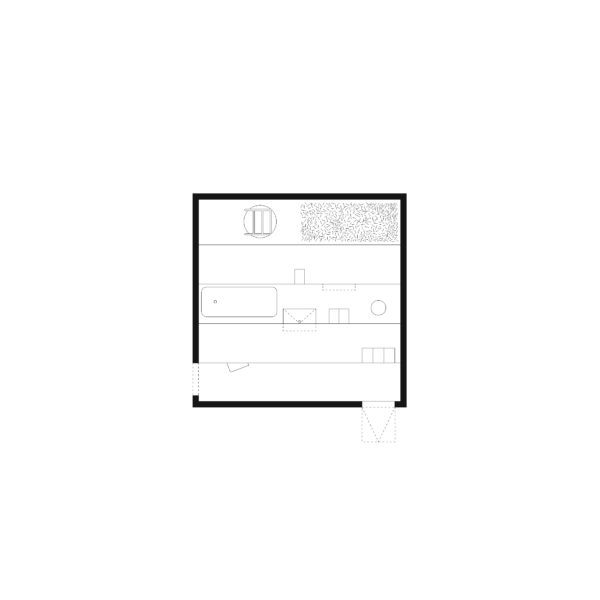

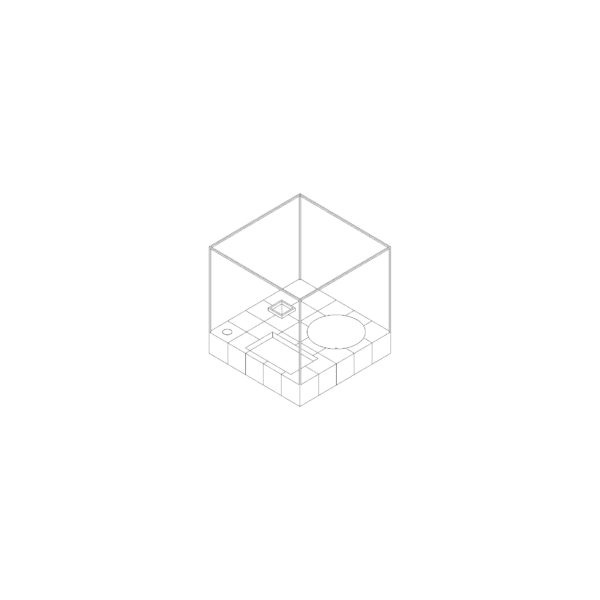

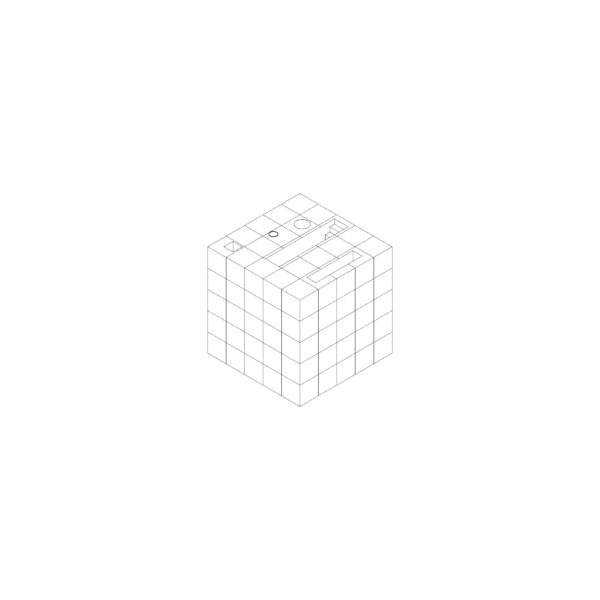

Based on a module of 80 centimeters, this cell is 4 by 4 by 4 meters. Larger than a mere existenzminimum, or a standard one-story dwelling unit, its layout is organized in five steps. Each one is 80 centimeters deep and progressively becomes lower in height to support a specific sequence of actions: a life distributed in vertical shelves.

In a life of work and creativity, leisure and meditation, we have considered four basic bodily necessities: sleeping, eating, washing, and excreting. Through centuries, each of these actions has been standardized, coded, symbolically loaded, and associated with social behaviors and relationships. Within this cell, each basic action is afforded its own condition and position, offering a rule for occupation that can be either followed or not.

At the lower level the possibility for clerical work and the annotation of daily thoughts and activities is provided for by a 80cm high stool and a desk. Any contemporary ascetic, willing to control life to its minute detail and gradually construct a form of living, is offered a space to write. As Foucault explains: “Writing about oneself appears clearly in its relationship of complementarity with reclusion: it palliates the dangers of solitude; it offers what one has done or thought to a possible gaze; the fact of obliging oneself to write plays the role of a companion by giving rise to the fear of disapproval and to shame.”8

On either side of the desk, cupboards are placed to ensure the storage of utensils. The large and long horizontal surface is positioned at a suitable height for preparing and consuming meals. Washing requires a basin of water for immersing the body. This void can either be dug into the ground, emerge from a wall, or be elevated above the floor. In the Cell for a Certain Individual, the water basin is embedded in the second shelf, which is 60cm high. On the opposite side, a defecating hole ensures a comfortable corner for squatting and emptying the bowels. In the middle of the step, and the whole pavilion, the hearth permits the warming of food and water, while heating the environment inside. The third step is dedicated to forms of mediation, and leisure. Providing a space to exercise and stretch, the step sits 40cm high and allows an occupant to sit down and look through the window at the surrounding landscape.

At the top, a sleeping surface is placed. The 20cm step facilitates rest through a soft horizontal plain to lay down upon, and ensures maximum bodily comfort and contact with the floor. Finally, as in many Carthusian cells, a workshop is provided below the staircase. Accessed through a ladder from inside and a doorway from outside, a high bench enables the occupant to dedicate time to practical duties and physical labor. With its position on the site of the Cartuxa de Laveiras, the Cell for a Certain Individual reestablishes an idea of collectivity through its singularity, in an attempt to bridge the lesson of the Carthusian form of living with a projective architecture for our present world.

3.

Carthusians refer to their cells as deserts. The cell is a remote site at the margins of civilization, distant from the noise of society and mundane temptations. A desert is not only the place where all customs, traditions, and historical stratifications fall apart, but also where any consolidated societal structure can be questioned and examined from an estranged point of observation.

The cell is neither an exodus nor a fugue from society but an instrument to sharpen the way we look at and dwell in the world. It offers a mental and spiritual shelter for cultivating new and radical forms of collective organization. It is the point of struggle between death and life, exhaustion and abstraction.

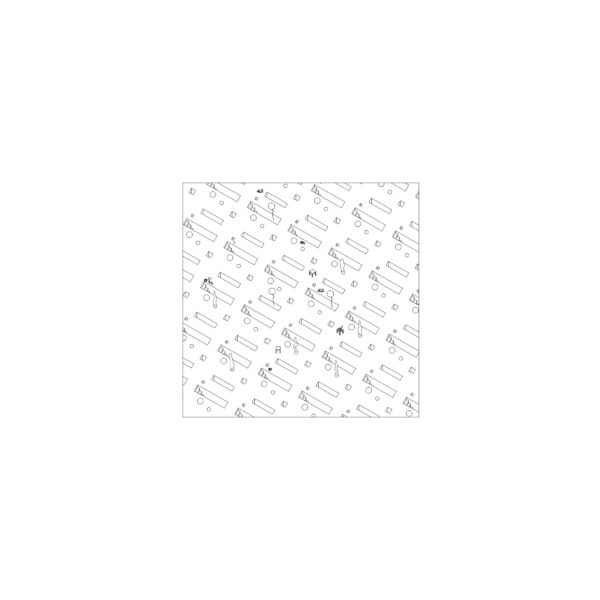

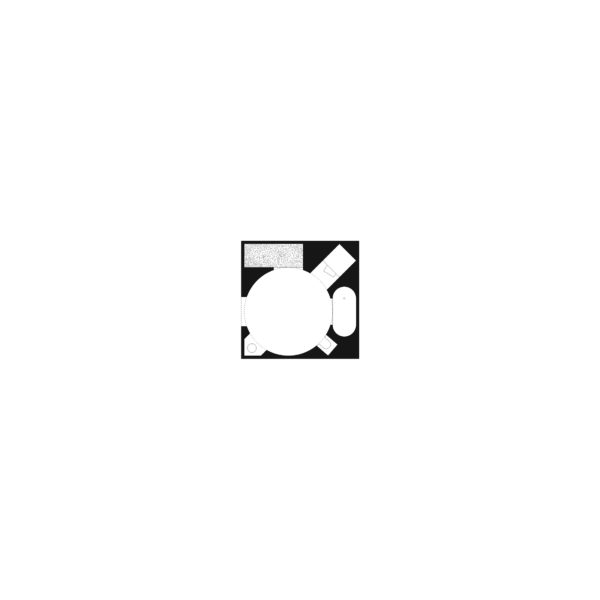

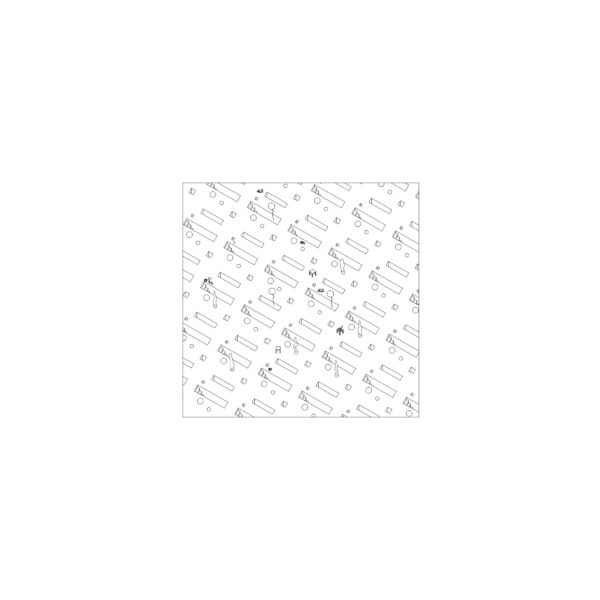

The metaphoric desert is thus a heuristic device to experiment with and rediscover ways of living, from the neolithic to the modern age, from Catal Huyuk to the Co-op Zimmer. Reducing contact with the world, each of the following eight deserts explores ways for creating new universes and rethinking the collectivity through shared rules of individual actions.

The cell does not provide objects, but rather only vertical and horizontal surfaces of different consistency to dissolve any intermediation between space and bodies into a meticulous architecture. The simplicity and emptiness of this zero-degree space exalt the naked concreteness of bodily gestures and their repetition. This distillation of dwelling to its most elementary forms implies different dynamics and a specific organization of necessary bodily actions: sleeping, washing, eating, and excreting. Each cell formulates an arrangement of the same gestures through various spatial devices, resulting in distinct configurations and different forms of living.

The four actions could be scattered across various islands as an archipelago of intensities or distributed around the boundary of the cell in a continuous inhabitable wall. They could be split by thick partitions or light membranes, separated in a series of equal compounds, or aligned in sequences. They could be arranged into a compact core, flattened on the floor or above the ceiling, separated by a chasm or a wall.

Traditional objects are thus stripped of their embedded social constructions and eroded to their quintessential uses. A table is neither round nor square but a surface at 80 centimeters above the ground. Similarly, a seat is a solid cube 40 centimeters wide; a bed is a soft surface above the floor measuring 80 by 200 centimeters; a bathtub is a concave basin containing 200.000 cubic centimeters; a toilet is a 30 centimeter hole in the ground; a circular stove acts as a hearth for fire which is necessary to process food, generate energy, and alter the temperature within the cell.

These primary forms establish a grammar for living in common. The simple aggregation of cells does not produce the collective; instead, the collectivity permeates each individual, passing through the singularity of each cell and the language it speaks.

A Certain Kind of Life was an associated project to the Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2019 “The Poetics of Reason,” realized in collaboration with our students Nash Kennedy, Alexandra Madsen, Jacob Patnode, William Stauffer, Julia Turner, Andreina Yepez, and thanks to the precious support of the University of Illinois at Chicago, and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

Notes

1.

The room is perhaps the fundamental element of any architecture. As a primitive hut, a simple shelter, a cave or a retreat, the room commands a unique and unrepeatable definition of a place. Making room means to clear a space for oneself: to identify a limit between inside and outside (room, from the proto-Indoeuropean root reue-“to open, space”).

Like organs in a body, specific arrangements of rooms correspond to species of buildings with distinctive characteristics. Despite its concatenations, a room always preserves the possibility of autonomy, as a stand-alone entity. In the Western classical tradition—from Vitruvius to Alberti and Palladio—rooms are usually categorized according to forms accurately proportioned to their fulfilled functions.

Within an imaginary catalog of rooms, the cell could be considered its contradictory expression. In opposition to the functional determinacy of the room, the nature of the cell is, in fact, ambiguous. A cell always implies its subordination to a larger whole, either considered as the hidden core of a temple (cell, from the Indoeuropean root kel-“to cover, conceal, save”), a storage room, or a more ordinary a small chamber. Its confined dimensions suggest the idea of being protected within a mass, contained in a sequence, or held in rhythm.

The cell speaks through the language of tissues and membranes rather than organs, referring to the whole body as its minute constituent atom. As a unit that could be repeated, it is inherently collective. Whereas the room can be indifferent to its surroundings, a cell is always deduced from the assembling logic of which it is part of. In this regard, it is not a coincidence that the use of cells characterizes particular collective buildings such as housing blocks, barracks, hospitals, schools, prisons, monasteries, and other institutions; all of which are based on compliance to a set of imposed measures.

A cellular organization constitutes the fundamental trait of any disciplinary regime. Cells compartmentalize space, minimize gestures, enclose bodies, and amplify control. In Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault remarks the relation between cell and confinement within the panopticon prison: “They are like so many cages, so many small theatres, in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible….He is seen, but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject in communication.” 1

For Foucault, the panopticon was a paradigmatic architecture: the spatial expression of a much wider social machine, the one that progressively instituted a disciplinary ensemble of norms and crimes, surveillance and punishment as a distinctive way of exerting power. The prison building, in this sense, was the formalization of a different composition of forces: a technology that already existed in the past but became relevant when a new sensibility in the art of punishment emerges in parallel to the evolution of penal law in the 18th century. In other words, the cell is a neutral architectural element that becomes extremely effective when innervated by specific power relations and inserted within a disciplinary diagram.

Not by chance, in his analyses of Bentham’s Panopticon, Foucault explains how similar architectures previously worked under different regimes of power and how the origin of the panoptic cellular segmentation was first experimented in Christian monasteries, where spaces for individual meditation and reclusion were juxtaposed next to collective facilities.2 Paraphrasing Robin Evans, the Panopticon stripped the soul out of the Christian monastery and made good use of its carcass, turning the anchorite’s voluntary withdrawal from the moral contamination of the world into the forced reclusion and permanent control over the prisoners.3

From here, the cell inherited many of the negative connotations we now hold of it: as the simple minimum space for survival, or the restrictive entity subjected to the authority and rigorous control of an external architectural apparatus. Yet, it would be a mistake to interpret the cell solely as an instrument of control and coercion. By reversing this perspective, the cell could instead be regarded as the constituent spatial module to imagine new forms of collective living. As a vessel to consciously limit and negotiate individuality within the broader societal domain, the cell might also help to discover how to live together through mutual acquaintance and construction of habits in common.

Solitary life does not connote a system of rules. For the isolated individual there is no problem of confrontation or negotiation, and hence no problem of form. Form only arises through the encounter and the negotiation of limits between different entities. The collective formulation of a rule coincides with the cellular concatenation.

The Cartuxa de Laveiras of Lisbon is, in this sense, paradigmatic. Established as a Carthusian monastery—where monks lived in permanent isolation from society within their cells—and later converted into a correctional center—where groups of teenagers were subjected to the order of the reformatory and lived within large dormitories fabricated from the destruction of the original monks’ cells—the Cartuxa demonstrates the alternative possibilities of an architecture of first chosen, and later imposed rules. More than a solitary retreat, or an assigned amount of inhabitable square meters, the cell was the instrument to refine a way of living that was collectively ordered, but individually enacted.

As the Carthusians would conceive it, the cell is a mental condition: a desert. The cell conceptually formalizes the desert where Jesus wandered fasting for forty days, fighting against evil temptations. Its constrained space embraces the vast extensions of a journey, which is “long, and the way dry and barren, that must be traveled to attain the fount of water, the land of promise.”4

Following the founder of the Carthusian Order’s aspirations, St. Bruno, the cell provides a space of solitude in which a form of life can be conducted under constant thought, without distractions and away from temptations. In the cell nothing is superfluous: every single object, space or ritual performed is necessary to the Carthusian monk for her journey of awakening. Life sediments within a constellation of firm points—a cubiculum for sleeping and a prie-dieu for praying, a table and a chair, the workshop, a garden with a porch—which becomes progressively more intense through constant repetition.

Such an extreme form of estrangement could be perhaps considered a valid paradigm especially in our contemporary condition. Living in a society that continually demands of us to exhibit, document, and share every single performed activity, a critical distance can steer us away from the apparatuses indexing out existences, our curated profiles and codified identities. Carthusian asceticism thus turns into a lesson of productive rationalism: an antidote against collective hypnosis, social bonds, constructed farces and imposed behaviors.

In the Genealogy of Morals, Friedrich Nietzsche redefines the notion of asceticism, not as a denial of existence or a withdrawal from society, but rather an affirmation of existence, a way to penetrate life in its most profound depths and to exalt the human potential. Zarathustra would abandon his retreat and descend from the mountains to the villages predicating a return to the earth and the body. The etymology of the word “asceticism”—from the Greek verb askein—indicates a form of exercising and training or, in other words, a way to rationally control the self, to administer its capacities and intensify the will to power.

Along the same trajectory, Max Weber distinguished an “outer-worldly asceticism,” entirely projected towards a complete detachment from mundane temptations, characterized by mysticism and hermetic contemplation, from an “inner-worldly asceticism” which instead demands a complete devotion to mundane activities. Weber finds the origin of this immanent form of asceticism in the Protestant concept of the “calling,” according to which the highest form of moral obligation for the individuals was to fulfill their duties in the society. In this way, labor becomes an absolute end in itself, a form of vocation and responsibility: a way of worshiping God through one’s worldly affairs.5

To Weber, the celebration of labor, crafts, and daily life activities celebrated by the Protestant ethics, revealed the emergence of new spiritual drive aimed at gaining profit for its own sake in the pursuit of a “calling:” the spirit of Capitalism.6 “The person who lives as a worldly ascetic is a rationalist”—Weber writes—“not only in the sense that he rationally systematizes his conduct but also in his rejection of everything that is ethically irrational, esthetic, or dependent upon his emotional reactions to the world and its institutions. The distinctive goal always remains the alert, methodical control of one’s pattern of life and behavior. This type of inner-worldly asceticism included, above all, ascetic Protestantism, which taught the principle of loyal fulfillment of obligations within the framework of the world as the sole method of proving religious merit, though its several branches demonstrated this tenet with varying degrees of consistency.”7

Such a mundane asceticism turns rationalism into an operative tool for increasing efficacy and control over daily actions. The austere space of the cell, minutely calculated to fulfill domestic necessities and rituals, becomes a testing ground to transform the mystic contemplation of monks into the immanent search for awareness of the alienated soul. Whereas the disciplinary regime subordinates the cell into a machine of constrictions, the inner-worldly asceticism transforms the cell into an instrument of emancipation and estrangement from the overwhelming spectacle of society in our everyday individual acts.

A Certain Kind of Life explores the typology of the Carthusian monastery as an architecture of absolute rationality, wherein the form of life cannot be detached from the space and rituals of the liturgy the monastery shelters. Drawing from nine centuries of monastic architecture, the project reconsiders asceticism as a way to meditate upon present living and working conditions: a necessary estrangement to look closely at reality, its daily gestures and rituals.

In a society wherein maximum integration generates maximum alienation, a rudimentary practice of asceticism offers both a strategy of resistance and an antidote against collective hypnosis, social bonds, and constructed farces and behaviors. The asceticism that A Certain Kind of Life advocates is a form of productive rationalism, to conduct life under constant thought by dispelling anxieties of endless competition, consumerism, and the consequential illusions of promise.

Taking place at the Cartuxa de Laveiras as an associated project of the 2019 Lisbon Architecture Triennale, A Certain Kind of Life proposes three interventions: a Cell for a Certain Individual, an architectural evocation of worldly asceticism; an Atlas detailing the charterhouse type in exemplary reiterations; and Deserts, an exhibition of prototypes for contemporary living, which distill the rationalism of daily rituals into architectural forms through specific procedures in space.

2.

From the solitary fugues of St. Antoninus or St. Paul in the Egyptian desert to the earliest experiments of isolated communities in Thebaid, Palestine, Judea, Syria, and North Africa between the third and fourth centuries, two primary forms of monasticism developed within the history of Christianity: the eremitic, corresponding to the solitary retreat from the world in remote hermitages, and the cenobitic, or the collective attempt to live together in isolation according to an established rule, confined within an architectural enclosure.

The Carthusian monastery, or charterhouse, offers a spatial combination of both of these forms of living: an architecture that inseparably connects the individual and collective dimensions through the sheer rationality of its spaces and the specificity of its observed principles. The charterhouse strictly separates the living quarters of the monks from the church, the chapter, the workshops, and the gathering halls, combining the various rhythms of the single inhabitants into a collective soul. Both a spiritual and physical form, the charterhouse has persisted since its foundation by St. Bruno in 1084.

Nothing could be added or taken away from its layout. In the charterhouse, nothing is owned, but everything is used. Every spatial aspect is defined by the requirements of liturgy performed: the highest spirituality is attained through the strictest definition of its silent ritual, resonating everywhere in the cloisters, objects, clothes, food, chants, gestures, and activities. When visiting the Charterhouse of Ema near Florence in 1910, Le Corbusier praised its respectful and harmonic combination of privacy and commonality, through which the individual and the collective juxtapose without merging, as in an idiorrhythmic ensemble. It was from this combination that he conjectured his 1922 project for the Immeubles-villas.

The plan of the Charterhouse is generally organized into three parts: the cells of the monks surrounding a large cloister; a buffer zone with collective programs such as church, chapter house, and refectory, where the daily officia and occasional events are held in common; and a public interface comprising productive facilities, services, and gathering areas—wherein a group of laymen and converse brothers live and interact with the external world, helping the Carthusian monks to preserve their autonomy from society. This part of the charterhouse adapts to the topography and specific contextual conditions, producing unique differences within the assemblage.

Each monk’s cell, or desert, provides necessary equipment for simple living: a bed, a prie-dieu, a table for studying or eating, a lavatory, a workshop, an ambulatory for recreation, and a garden. The liturgy is what prescribes the life of the monks: it is the form-giver to their activities performed in silence and contemplation. Every single action—praying, reading, studying, working, eating, or resting—is performed in a specific space and inscribed in the plan of the cell and its equipment. From midnight to the afternoon, a series of silent collective gatherings harmonically intersects with the individual rituals in the cell.

The Cell for a Certain Individual reinterprets the Carthusian monk’s desert as a refuge from the congestion and the hectic rhythms of society. The asceticism of the cell is neither an escape nor a voluntary exodus from the world, but, on the contrary, a total immersion in it: a way to rediscover and reinvent ourselves, rendering the world at a sharper resolution. In this way, the cell turns into a mirror, a window to look at ourselves and critically reframe our daily rhythms and chores.

Based on a module of 80 centimeters, this cell is 4 by 4 by 4 meters. Larger than a mere existenzminimum, or a standard one-story dwelling unit, its layout is organized in five steps. Each one is 80 centimeters deep and progressively becomes lower in height to support a specific sequence of actions: a life distributed in vertical shelves.

In a life of work and creativity, leisure and meditation, we have considered four basic bodily necessities: sleeping, eating, washing, and excreting. Through centuries, each of these actions has been standardized, coded, symbolically loaded, and associated with social behaviors and relationships. Within this cell, each basic action is afforded its own condition and position, offering a rule for occupation that can be either followed or not.

At the lower level the possibility for clerical work and the annotation of daily thoughts and activities is provided for by a 80cm high stool and a desk. Any contemporary ascetic, willing to control life to its minute detail and gradually construct a form of living, is offered a space to write. As Foucault explains: “Writing about oneself appears clearly in its relationship of complementarity with reclusion: it palliates the dangers of solitude; it offers what one has done or thought to a possible gaze; the fact of obliging oneself to write plays the role of a companion by giving rise to the fear of disapproval and to shame.”8

On either side of the desk, cupboards are placed to ensure the storage of utensils. The large and long horizontal surface is positioned at a suitable height for preparing and consuming meals. Washing requires a basin of water for immersing the body. This void can either be dug into the ground, emerge from a wall, or be elevated above the floor. In the Cell for a Certain Individual, the water basin is embedded in the second shelf, which is 60cm high. On the opposite side, a defecating hole ensures a comfortable corner for squatting and emptying the bowels. In the middle of the step, and the whole pavilion, the hearth permits the warming of food and water, while heating the environment inside. The third step is dedicated to forms of mediation, and leisure. Providing a space to exercise and stretch, the step sits 40cm high and allows an occupant to sit down and look through the window at the surrounding landscape.

At the top, a sleeping surface is placed. The 20cm step facilitates rest through a soft horizontal plain to lay down upon, and ensures maximum bodily comfort and contact with the floor. Finally, as in many Carthusian cells, a workshop is provided below the staircase. Accessed through a ladder from inside and a doorway from outside, a high bench enables the occupant to dedicate time to practical duties and physical labor. With its position on the site of the Cartuxa de Laveiras, the Cell for a Certain Individual reestablishes an idea of collectivity through its singularity, in an attempt to bridge the lesson of the Carthusian form of living with a projective architecture for our present world.

3.

Carthusians refer to their cells as deserts. The cell is a remote site at the margins of civilization, distant from the noise of society and mundane temptations. A desert is not only the place where all customs, traditions, and historical stratifications fall apart, but also where any consolidated societal structure can be questioned and examined from an estranged point of observation.

The cell is neither an exodus nor a fugue from society but an instrument to sharpen the way we look at and dwell in the world. It offers a mental and spiritual shelter for cultivating new and radical forms of collective organization. It is the point of struggle between death and life, exhaustion and abstraction.

The metaphoric desert is thus a heuristic device to experiment with and rediscover ways of living, from the neolithic to the modern age, from Catal Huyuk to the Co-op Zimmer. Reducing contact with the world, each of the following eight deserts explores ways for creating new universes and rethinking the collectivity through shared rules of individual actions.

The cell does not provide objects, but rather only vertical and horizontal surfaces of different consistency to dissolve any intermediation between space and bodies into a meticulous architecture. The simplicity and emptiness of this zero-degree space exalt the naked concreteness of bodily gestures and their repetition. This distillation of dwelling to its most elementary forms implies different dynamics and a specific organization of necessary bodily actions: sleeping, washing, eating, and excreting. Each cell formulates an arrangement of the same gestures through various spatial devices, resulting in distinct configurations and different forms of living.

The four actions could be scattered across various islands as an archipelago of intensities or distributed around the boundary of the cell in a continuous inhabitable wall. They could be split by thick partitions or light membranes, separated in a series of equal compounds, or aligned in sequences. They could be arranged into a compact core, flattened on the floor or above the ceiling, separated by a chasm or a wall.

Traditional objects are thus stripped of their embedded social constructions and eroded to their quintessential uses. A table is neither round nor square but a surface at 80 centimeters above the ground. Similarly, a seat is a solid cube 40 centimeters wide; a bed is a soft surface above the floor measuring 80 by 200 centimeters; a bathtub is a concave basin containing 200.000 cubic centimeters; a toilet is a 30 centimeter hole in the ground; a circular stove acts as a hearth for fire which is necessary to process food, generate energy, and alter the temperature within the cell.

These primary forms establish a grammar for living in common. The simple aggregation of cells does not produce the collective; instead, the collectivity permeates each individual, passing through the singularity of each cell and the language it speaks.

A Certain Kind of Life was an associated project to the Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2019 “The Poetics of Reason,” realized in collaboration with our students Nash Kennedy, Alexandra Madsen, Jacob Patnode, William Stauffer, Julia Turner, Andreina Yepez, and thanks to the precious support of the University of Illinois at Chicago, and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

Notes