Mostly they died in ways like anyone else. The fifty-seven year old Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, who enthralled Paris audiences with suite of exotic genre and biblical subjects following a year in Asia Minor in 1829-1830, perished in August 1860 after being thrown by a horse, near his home in the forest of Fontainebleau.1 Léon Belly, whose Pilgrims Going to Mecca of 1861 remains one of the best-known Orientalist pictures of the nineteenth century, died in Paris in 1877 after a long and debilitating illness. The French art world was shaken by the news of this artist cut down at the age of fifty, but there was nothing Orientalist about the manner of his death, no reports of dramatic last words or studio deathbed scenes.2 We know even less about how the end came to Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouÿ, a student of Ingres and best known for his White Slave of 1888. His death in Paris in 1921 at the age of eighty-one attracted little attention, silence traceable in large part to a historic artistic reset that saw so many academic masters of the nineteenth century fall into obscurity. To repeat, Orientalist painters left the world under varied circumstances — violent, painful, peaceful, or in ways simply unknown, in other words just like anyone else. And yet the basic argument of this essay is that how Orientalists died is not only an empirical but discursive question. From this latter perspective, their manner of passing would be mediated across a rich poetics of mortality whose shape and texture these remarks explore.

Sometimes an Orientalist simply died a painter’s death. Nothing as emblematic or status-driven as Raphael dying after painting Christ’s face on his unfinished Transfiguration, or Leonardo da Vinci dying in the arms of Francis 1st, to cite two notable deathbed scenes, recounted by Vasari, that Romantic artists took up with gusto. Nevertheless, examples abound of nineteenth-century artists who died in a manner that in some measure evoked their artistic vocation. Take the case of Charles Gleyre, a Swiss painter working in Paris remembered today mostly for his Lost Illusions of 1843, a talismanic, Orientalizing scene of fatalistic disillusion. Three years in Greece, Egypt, and Syria in the mid-1830s saw Gleyre nearly succumb both to fever and severe ophthalmia, including ten months where he lay nearly blind in the vicinity of Khartoum.3 Gleyre’s experience in the Middle East was said to have left its mark on the famously grave and taciturn artist. The end, however, did not come until May 1874, when the sixty-eight year old artist collapsed while viewing an exhibition in support of the lost provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, at the Palais Bourbon.

His biographer Charles Clément, rushing to Gleyre’s house to view his friend’s body, noted that his “tired features, so often wracked with pain,” seem “relaxed.” The painter’s face bore “an extraordinary expression of calm, peace, and serenity.”4 Note that Clément is anxious to stress the precise circumstances surrounding Gleyre’s last moments: the exhibition on behalf of the lost provinces, the gallery where he fell, the fact that he was accompanied by a student, walking with deference “a few steps behind.” He also noted the time of day–precisely 11:50, Clément explained, Gleyre arriving in time still to qualify for half-price admission. Here as elsewhere, the broadly positivist protocols of nineteenth-century biography did not tolerate the kind of strategic fictions that populate Vasari’s deathbed scenes. And yet it’s tempting to treat this recitation of details as embedding a poetics of its own. The site of Gleyre’s death, to be sure–to drop dead in a museum, surely that is a painter’s death; note, too, the image of the respectful student following a few steps behind. And let us not omit the allusion to Gleyre’s parsimoniousness, which Clément cites to pinpoint the time of death, but which also serves as ironic counterpoint to the catastrophe shortly to unfold. Finally note the narrative takes an Orientalist turn, Clément evoking the sense of serenity on Gleyre’s features following his release. Clément imagines Gleyre at last free of physical torments that dogged him from his months in Egypt, torments that nurtured his fatalistic disposition and marked him to the grave.

Eugène Fromentin did not die an “Orientalist” death either, but as with Gleyre, his biographers could not resist bringing Fromentin’s experience in North Africa into play. Fromentin’s Street at Laghouat from the Salon of 1859 emerged as a touchstone of Orientalist art criticism, and to this day his journals recounting his travels to Algeria stands today as among the most accomplished examples of the genre. The fifty-six year old Fromentin died in 1876 in his hometown outside La Rochelle, on the Atlantic coast. He only recently had failed (again) to secure a seat at the Institut, although in literature rather than the section for painters. The prospects of a chair in painting, Fromentin knew, were slim — a career consisting of genre paintings or mere tableaux de circonstance would never qualify him for his profession’s highest honor. Fromentin’s biographers, for their part, evoked a sense of Orientalist irony. Hence the phrase of Emile Montégut, who cited an Arab proverb as he spoke of Fromentin succumbing just as he was in the full maturity of his powers, and on the point of being properly recognized: “When the house is built, death comes and slams the door,” Montégut observes, explaining that certainly Fromentin knew this “fatalistic” proverb, in which seemed “condensed” all the wisdom of the Orient. Surely Fromentin’s “sudden disappearance,” Montégut adds, so “unexpected,” offered a “lugubrious” and alas “all too justified” demonstration of the proverb’s veracity.5

The idea that Fromentin’s death offered an ironic fulfillment of the lessons learned on his travels to Algeria operates as more than rhetorical conceit. We find many similar statements across the corpus of Orientalist artistic biography, as friends and biographers brought to their obituaries and memorial essays a poetics of endings that entwined art and death along an Orientalist axis. In some cases critics improvised with a light touch, Montégut’s phrase about Fromentin offering a case in point. But in other cases the figuration was more ambitious, encompassing for example a painter’s last words, the manner of his death, the kind of memorial made for him, or for that matter who turned up at his funeral. And as the example of Gleyre suggests, the broadly positivist protocols of nineteenth-century historical writing were scarcely immune from such figuration and indeed might be said to have offered this poetics new force and grip. How an Orientalist painter died, to repeat, was not just an empirical but a discursive question, and we must treat such end of life stories as a rich, aspirational, and broadly vocational mythology, at once varied and malleable as per the circumstances of the case, even as certain themes and motifs recur in a manner open to historical and rhetorical analysis.

From Leonardo to Raphael and many others, accounts of artists’ deaths by Vasari and his successors offer an important precedent for these concerns. Across painting, biography, and illustration, artists, critics, and illustrators rewrote the biographies of the old masters through the filter of their own aesthetic and critical positions. We generally treat pictures depicting the last moments of Leonardo, Michelangelo, Titian, and Raphael as doing strategic work, nineteenth-century artists seizing on their presumed ancestors as historical aliases and fashioning a mediated image of the present. And yet the topic of how nineteenth-century artists died remains by and large unexplored. Certainly it might seem hard to elicit from nineteenth-century data the topoi, mythical residue, or “biographical cells” that Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz explored in stories told about artists from antiquity to the Renaissance.6 We commonly associate nineteenth-century life writing with the emergence of positivist evidentiary protocols inhospitable to the kind of mythic formulae projected onto the old masters. The catalogue, the retrospective, the artist’s correspondance, and other instruments of modern artistic biography were generally hostile to figurative play. And yet the emergence of this historiographical edifice should not obscure the sheer fertility of meaning-making associated with artists’ death, meaning-making operating not just side by side but embedded within the edifice itself. That poetics, in short, was sometimes all the more powerful since it took the form of simple description and in this sense did not seem like mythmaking at all.

Only rarely did the deaths of nineteenth-century artists qualify for visual illustration, still less were they staged in drama or fiction. The Death of Gericault, painted in 1824 by a member of his circle, offers an important exception in this regard, notable in part because of its association with a death mask of the Gericault that proved crucial to the legend of the artist as it took shape. Alexandre Decamps painted The Suicide in 1835, inspired it was held by the suicide earlier that year of Léopold Robert. Alexandre Menjaud completed Girodet Bids Farewell to his Studio in 1826 shortly after the master’s death, but despite these examples such visual evocations are rare. By and large, for the nineteenth century these practices of figuration lie on textual terrain, from formal artistic biographies to obituary notices and casual recollections circulated in the press. Inscribed within and sometimes working against the secular protocols of life-writing that eventually came to dominate such writing system wide, they open a revealing window onto the psychologically and historically configured imperatives that shaped and structured an artist’s vocation, from their studios to their deathbeds.

Let me make two additional points before developing a series of examples in greater detail. Whether the deaths of Orientalist artists inspired a more varied or elaborate poetics than, say, the deaths of landscape or history painters in the nineteenth century, is an important question that lies beyond the compass of the present study. “The Sun is God,” Turner is said to have uttered on his deathbed – arguably the most famous last words by any artist (the tale traceable to Ruskin, although whether Turner said them is doubtful). But by way of a preliminary hypothesis, I want to argue that a combination of historical, geopolitical, and cultural factors combined to give Orientalist narratives of mortality singularly deep purchase. Many recent accounts of nineteenth-century Orientalist painting emphasize its invented, idealized, and indeed ideological character – ideological work, as the argument goes, that operates invisibly thanks to that painting’s typically realist idiom. Whether or not we sign on to the charge, at the very least we may say that precisely Orientalist’s invented and escapist character offered a ready platform for end-of-life narratives to take flight. Orientalism perhaps most of all among nineteenth-century art movements nurtured an elegiac poetics of mortality, loss and exile that left painter and career, life and art, mysteriously and sometimes fatally – like “The Orient” itself — intertwined.

Finally, I want to make the additional point that for all its richly imaginative character, this poetics was not simply born from studio voyages. It was fruit of the broadly naturalist climate of the mid- and later-nineteenth century, as Western artists travelled to North Africa and the Middle East, and the profession of the painter-traveler took shape. Each of the artists discussed in this essay actually journeyed to “The Orient,” several of them on multiple occasions and two (Fromentin and Gustave Guillaumet) leaving behind important literary monuments. Following in the tracks laid by colonial expansion, painters and illustrators established commercially successful practices that highlighted the first-hand, observational basis of their exotic representations. Needless to say, artists also mined the classic tropes that in the Western imagination defined the region’s climate and geography — the desert, the caravan, and the oasis, among others. But it was the reality of such journeys that gave this poetics special feeling. Such travel, as it seemed, marked a painter’s eyes, body, speech, and affect — in short how painters lived and how they died.

Death Abroad

The risks were real. The Scottish born history painter David Wilkie died at age fifty-six outside Gibraltar aboard the steamer SS Oriental in June 1841, en route home from Syria and Constantinople. The exact cause of death is uncertain, but the surgeon aboard the Oriental, who took careful notes as Wilkie deteriorated, writes that the artist came aboard in Alexandria already sick, and that his condition deteriorated rapidly following the consumption of fruit and iced lemonade purchased during a stop in Malta. The Spectator reports that passengers on the steamship lobbied the captain to bring Wilkie’s body ashore, but the Governor at Gibraltar refused permission and the artist was buried at sea that evening at 8:30 pm, just before sunset.7

The availability of the surgeon’s notes helped assure that Wilkie’s biographers would confine themselves to clinical descriptions of his final hours. His death resonated in British visual culture for decades after, however, thanks in large part to his friend J. M. W. Turner, who made Wilkie’s burial at sea the subject of one of his most famous pictures. “The midnight torch gleam’d, o’er the steamer’s side,” explained Turner in The Fallacies of Hope, when his Peace-Burial at Sea was first exhibited in 1842 (along side War, The Exile and the Rock Limpet, a pendant also themed on the topic of exile, and featuring Napoleon on the Island of St. Helena). Ruskin, as it happens, was disparaging about Turner’s use of black, and many other critics found fault in Turner’s disinclination to describe the event with exacting accuracy. But eventually it became one of the artist’s best-known pictures, routinely inspiring more sympathetic viewers to spiritual heights. Turner, explained Ralph Nicolson Wornum, keeper of the National Gallery, in account of the picture published next to a mezzotint by Alfred-Louis Brunet-Debaines, was not the kind of artist to be “tested by realism.”

Nor might we add was Turner tested by the facts of the case. The burial time of 8:30pm was widely noted, but perhaps in an effort to motivate the great contrast of light and dark that so puzzled the picture’s first viewers and continues to puzzle scholars into the present day (Paulson goes as far as to suggest the great mass of black on the ship is in fact a London stagecoach, an allusion to the burial at home that was denied to Wilkie), Turner sets the hour at midnight, as if to dramatize the symbolic darkness of the occasion by a striking contrast of light and dark. And while the light is torchlight, John Mollet described the picture’s effect of hyper-natural illumination as almost “mystical” in character — a “great flood of crimson light that seems to consecrate the temporary chapel of the waist of the ship, and the coffin’s plunge into the illuminated wave of crimson flood of light.”8 Of course Mollet was right – transcendent effects of light dominate Turner’s art through and through. But on this occasion we may say that Turner adapts that commitment to a metaphorics of illumination already inscribed in Orientalist painting and criticism, a claim we will have occasion to revisit in the remarks ahead.

Another example, in this case an artist who perished in the field. Clément Boulanger, a pupil of Ingres, saw success at the Salon in the 1820s and 1830s before signing up in 1841 as recorder to an archeological expedition led by Charles Texier to the ancient city of Magnesia, in the Meander Valley. As Alexandre Dumas recalled in his recollections of the artist, in September 1842 the group was at work excavating a magnificent temple to Diana, destroyed in an earthquake and now partially under water. Unwisely seeking to complete a sketch “in the full heat of the midday sun,” Boulanger succumbed to a “one of those bouts of sunstroke, so dangerous in the Orient.” Achmet Bey, the Governor, sent his carriage and attendants “for the use of the sick man,” but too late, and the only medical treatment available was from “bad Greek doctors, like those that killed Byron.” A report in the Smyrna Journal, reprinted in the French press, adds that upon being taken ill, native workers at the site were sent off to fish for leaches (Byron was also bled), but the physician in charge of treatment was not a Greek native but rather was attached to their ship, L’Expéditive.9 Falling into a delirium, Dumas continues, Boulanger was set in a hammock in a nearby mosque and died within five days, “singing and laughing” but “not doubting he was dying.”10

The funeral of this thirty-seven year old painter was prestigious. Boulanger’s body was transported to Scala Nova (present day Ku?adas? in Turkey) by horse, attended by “eight Greeks” and a dozen sailors from L’Expeditive. Reports in the French and English press add that that the ceremony drew local diplomats as well as a contingent of clergy, not to mention all the Christian residents of the city, who gathered to meet the cortege upon its arrival. Dumas claimed that no less than three thousand people trailed Boulanger’s coffin by the time it arrived at the French legation in Constantinople – quite wrong, since the body never travelled there. But we do know that in a show of patriotic solidarity, French houses and commercial institutions adorned their facades with funeral banners and flags, as did ships offshore. Other locals, too, it was reported, would pay their respects to fallen artist. To be sure, the stakes for these communities differed, sited as they were on hierarchically distinct positions on the “imaginative geography” (Said’s term) that mapped Boulanger’s path to the tomb. But in each case, the honors shown an artist charged with retrieving a community’s lost or forgotten history operates as a legitimating topos of imperial culture, just that homage seeming to fuel a sense of solidarity on the ground, and reported up to readers back home.

This cultural work of mourning operates not only over space but over time, the deaths of Boulanger and Wilkie sending out a lingering after-image of the painter-traveller’s journey gone awry. “Poor Clément Boulanger,” writes Louis Gonse in the Gazette des beaux-arts in 1874, upon encountering one of his pictures in Lille. “He rests now, unknown, in the cloister of a Greek church in Smyrna, where probably no traveller thinks of going to render him pious homage.”11 In fact this was not quite right — Gonse’s lament for Boulanger’s forgotten tomb was enabled in part by the fact it was not forgotten, but rather formed part of an elegiac, Orientalist tour. Travelling to Constantinople a decade later after Boulanger’s death, Théophile Gautier reports encountering a plaque honoring Boulanger in the exterior cloister the Greek Church near the marketplace in Smyrna. “The Tomb of a compatriot in a foreign land,” confessed Gautier, has always something of a sadness in its associations, be it from an unacknowledged selfishness of humanity, or from a vague impression that the foreign soil presses more heavily upon the ashes which it covers.”12 Note the chance character of the encounter. It may well be that Gautier had been informed of the memorial, or that his guide took him to see it. But in the narrative as he stages it, serendipity leads him to explore a mysterious cloister in a provincial town, only to discover the faded trace of another who preceded him. “Foreign soil,” Gautier explains, seemed to press “more heavily” on the fallen artist than burial in his native land, although of course what Gautier means is that it pressed more heavily on himself, his encounter with Boulanger’s ashes catalyzing traveller’s anxiety for home. Other travellers, too, in the years ahead, took note of the plaque and sent in reports for readers back home, including Adolphe Joanne and Emile Isambert in 1861, and Emile Bourquelot in 1886.13 A mournful poetics of the forgotten exile rested on the possibility of sometimes being remembered. For Boulanger this took the form of an actual site on a cultural and archeological tour. But the principle obtains for Wilkie as well, British travellers steaming past Gibraltar taking note of the approximate location where the SS Oriental consigned their compatriot to the deep.

Sacrifice and Representation

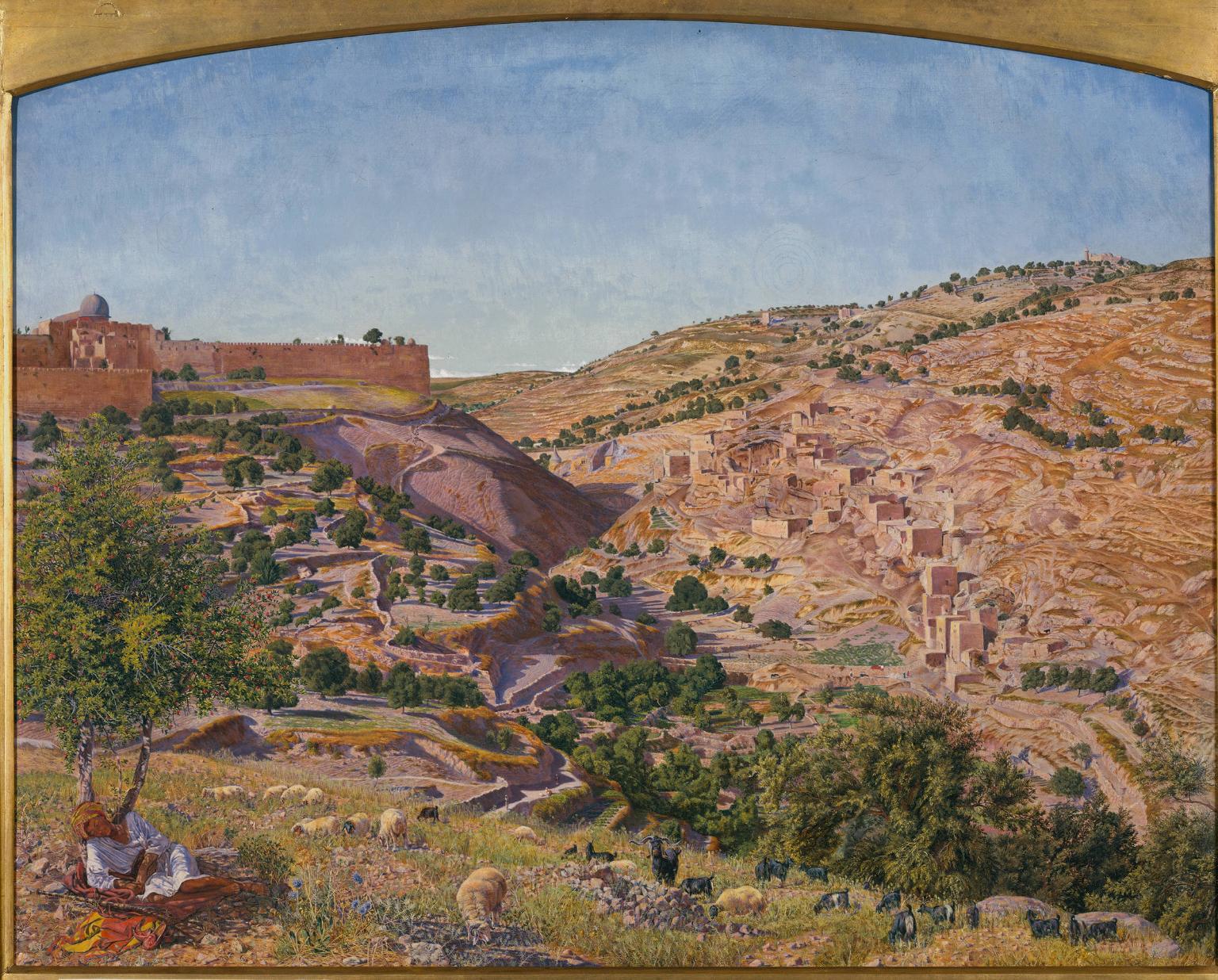

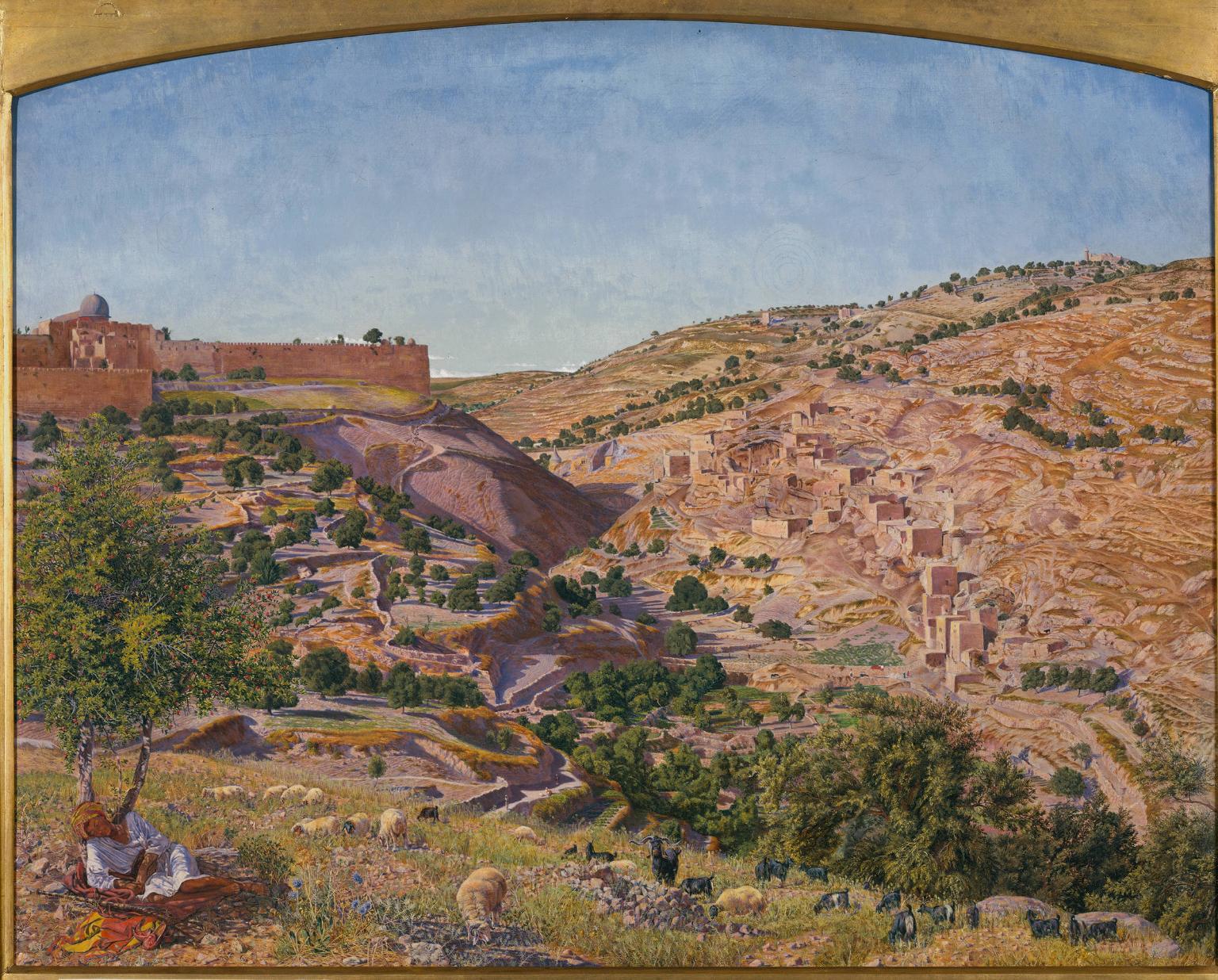

Another death in the field saw friends rally round a painter in an effort to inscribe his fatal pilgrimage in the canon of British art. Affiliated with the Pre-Raphaelite circle, Thomas Seddon died of in November 1856, at the age of thirty-five, while on his second visit to Cairo. Three years earlier the born-again Christian had accompanied Holman Hunt on a voyage to Egypt and subsequently Jerusalem, pitching a tent in the surrounding hills and studying its sites. From this campaign Seddon completed what is generally regarded as his masterpiece, Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from the Hill of Evil Counsel, whose striking topographical and geological accuracy inscribes a tri-partite allegory of resurrection readily accessible to a viewer informed by similar Christian fervor. Commercial success cemented Seddon’s conviction he should return to the Middle East, again with the idea of undertaking sacred subjects, and to which he proposed to bring a new level of documentary veracity based on first hand-observation of the region’s topography, flora, and geology. The motivation for this disciplined program was less artistic than educational – precisely by sacrificing, as it seemed, fatuous claims to originality, Seddon could present the Holy Land to audiences back home for their religious benefit: “He wished to present to those who could not visit it an accurate record, not a fancy view, of the very ground our Savior so often trod,” explained Seddon’s brother, in a note to The Atheneum in 1879.14 All of this is to say that Seddon’s embrace of unmediated realism was less an aesthetic position than a moral obligation. His conviction he must forego anything “fancy” constituted a willing and deliberate act of artistic selflessness.

Within a few weeks of his arrival in Cairo, Seddon came down sick — “thrown for a sharp curb,” he wrote his wife, indeed perhaps “punished” for “a want of attention to His Sabbath,” Seddon confessing to having walked the streets and alleys after church on Sunday, rather than returning home to rest.15 The days ahead offered an uncanny mirror-reversed image of an earlier experience: during his first trip to Egypt, Seddon had nursed a fellow traveller known only as Nicholson, moving him from Cairo to the Pyramids as he declined and finally died. But on this occasion, as commentators rued following a memoir on Seddon published by the artist’s brother, it fell to a physician and missionary in the Cairo community of expatriates to take this obligation on: “and when, after no long period, he himself lay on his deathbed, in the same land of strangers, it is touching to know that a friend as devoted was raised up to him, and the cup of cold water he had given to another held to his own parched lips by a gentle Christian hand.”16 A mere four weeks following his arrival Seddon was dead, felled by dysentery in all likelihood acquired on the passage from Marseilles.

Needless to say, Seddon’s death struck friends and admirers hard, many of them yielding to magical thinking in an effort to assign agency where there was none. Look no further in this regard that Seddon himself, whom as friends report, had recently confessed to intimations of mortality. He neither “expected nor desired,” Seddon’s brother recalled, “to be long lived.” Indeed it “really seemed as if he felt a presentiment of his death, and was studiously making preparation for it.” Seddon’s circle of friends found comfort in this notion, Seddon’s serenity and good nature in the face of these intimations helping to lift the pall cast by his death and mobilizing their commemorative work in turn. The tragic outcome of his second tour would be assimilated to a divinely inspired master plan. The death of this artist in the field was not simply an occupational hazard, but the highest expression of his devotion and even his destiny. The quest for first-hand observation that underwrote his journey was a spiritual quest through and through, an artistic version of an ethics of sacrifice that found its highest expression in Seddon’s early passage into eternal life.

All this and more informed the attitudes of his friends when they gathered at the house of Ford Maddox Brown for the purpose of preserving Seddon’s memory in the annals of British art. Together with Holman Hunt, John Ruskin, and others in the Pre-Raphaelite circle, they launched a subscription campaign to acquire Seddon’s Jerusalem for the nation, in the end purchasing the picture for six hundred pounds and offering it to the National Gallery. This, too, as it seemed, was part of Seddon’s master plan. His brother reports that he had proposed to let the picture go at a low price to a collector, with the proviso it be offered to the Gallery after his death; and that in still another scheme, Seddon had planned to present a large copy of the picture for a “public institution,” so that others may have “a correct representation of the very places that were so often trod by our Redeemer during His sojourn on earth.”17

For an account of Seddon’s aesthetics self-effacement, look no further than Ruskin, who praised Seddon’s Holy Land subjects for their absence of art. It was Seddon’s presence there, Ruskin explained, and the mortal risks that presence entailed, that assured the truthfulness and sincerity of his pictures, and hence his seeming invisibility at the scene of representation. Seddon’s landscapes, Ruskin explained, were “the first” to unite “perfect artistical with topographical accuracy.” The first to be “directed, with stern self-restraint, to no other purpose than to giving those who cannot travel, trustworthy knowledge of the scenes which ought to be most interesting to them.” All previous efforts at truth in this area had been “more or less subordinate to pictorial or dramatic effect,” in other words what Seddon’s brother had termed “fancy.” For Seddon anything fancy was absent. His “primal object,” Ruskin insists, was to “place the spectator, as far as art can do it, in the scene represented, and to give him the perfect sensation of its reality, wholly unmodified by the artist’s execution.”18 It is hard to imagine a fuller statement of an of artful self-sacrifice – artful because the guarantor of Seddon’s invisibility was the fact he was there, his presence assuring his viewers they were seeing the truth even as he relinquished all claims for this art and put his own life at risk. Seddon’s humble dream of unmediated realism on another’s behalf stands as artistic counterpart to his own readiness to follow the path of Christ, literally and figuratively to the Promised Land. Surrendering his art for the sake of a truthful representation, Seddon’s death was not simply a risk associated with his voyage but in a sense its fulfillment — hence Ruskin, as he called on the public to throw itself behind “the sacrifice of the life of a man of genius to the serviceable veracity of his art.”19

The Sun and Death

“Light!” exclaimed Henri Regnault as he fell in January 1871, his “last cry” evoking the immersive, sun-filled dream that took him from Paris to Rome, Madrid, Granada, and finally Tangier.20 Doubtless it is farfetched to imagine the famous hero of the Franco-Prussian War, killed outside Paris on a cold, gray afternoon, to have shouted out the word encapsulating his journey to “the land of the sun” — not least of all because no one saw him fall. But the tale, sent around three decades later by Gabriel Hanotaux, a leading historian and diplomat, speaks to the currency of an Orientalist poetics of illumination that so colored Regnault’s memory that readers could imagine exactly that. For Regnault as for many others, a well-trodden metaphorics of light came utterly to saturate Orientalist art criticism and artistic biography, the sun seeming at once to illuminate their artistic path but also trail them to the grave.

Countless painter-travellers would be described as setting out for the “land of the sun,” at once in an effort to brighten their palettes but also in search of a deeper sense of artistic renewal. The sun stands as a figure of vocational rebirth, artists recharging their enterprise in the face of climatic and atmospheric effects that bordered on the inimitable. Reentry, accordingly, was invariably difficult, Orientalist painters suffering and even dying from withdrawal under the grey skies of Northern Europe. The thirty-six year old Prosper Marilhat, for example, seemingly “haunted” by his journey to the Orient, was “suffocated by the fogs of the North.”21 Théodore Chassériau, a pupil of Ingres but “touched” by Delacroix, made several trips to Algeria only to be cut down in Paris in 1856, at the age of thirty-seven. Chassériau, lamented Gautiert, “sleeps in the darkness of the tomb,” an ironic fate for this “ardent artist who loved the sun” and whose paintings made Gautier “drunk with light” (more on Chassériau shortly).22

Deathbed narratives rewrote the painter’s journey into the sun in spiritual terms, the tracks laid by an Orientalist culminating in a final encounter that marked his passage into eternal life. Take the case of Charles de Tournemine, an underrated Toulon-born painter and curator at the Luxembourg museum (and model for the Orientalist painter Coriolus in the Goncourt’s Manette Salomon).23 Tournemine made several trips to Algeria, Asia Minor, and Egypt in 1850s and 1860s, including an invitation in 1869 to attend the inauguration of the Suez Canal. After helping to safeguard the Luxembourg’s collections during the Franco-Prussian War and Commune, Tournemine returned to his native Toulon to nurse his deteriorating health. To no avail, however, Toulon dying in 1872 following a slow decline in his physical and mental faculties. J.L. Turrel, a noted physician, naturalist, and supporter of the arts in Toulon and Marseilles, reports that in his last days Tournemine fell into a delirium, the artist confusing past and present as he imagined himself once again in the land of the sun. Tournemine’s “poor mind, feverish from sun,” sought a final journey into the light — “he wanted to forge straight into these lands of the sun that he had so loved and were the aspiration of his life.”24 Indeed even to India, its “sun and fruits” tempting his now unhinged mind. But if the illness was “cruel,” the “agony was gentle,” the physician insists, for in the end Tournemine regressed to a childlike state, and the “doors of his tomb” opened precisely in the “crib.” As from “chrysalis to butterfly,” Tournemine finally found himself on the threshold of “what was always his ideal, towards the great, eternal light.”

The lamented Marilhat, remembered today in a striking portrait by Chassériau, offers another version of this regressive scenario, alas less redemptive than poignant and strange. Returning to Paris in the spring of 1833 after a long voyage to Egypt, where he served as recorder to a scientific expedition before eventually striking out on his own, Marilhat sent to the Salon a suite of landscape and urban subjects that captured the interest of Gautier and other Romantic critics. And while he never returned to the Middle East, Marilhat continued to mine this youthful journey until 1847, when syphilis sent the thirty-six year old painter to the grave. Critics who knew him noted creeping signs of mental illness overtook Marilhat in the early 1840s, triggered in part by an unexpected blow to his artistic pride. In 1844 he was nominated for the Légion d’honneur by his ally Prosper Marilhat (or at his urging), only to be rejected. The news came as a shock, although this was hardly a surprise given his youth. In fact later that year Marilhat received something like a consolation prize in the form of a substantial commission that would have allowed him to return to Egypt or elsewhere in North Africa and the Middle East. But this could not soften a blow that embittered the artist and seemed to fuel his instability.

As the delusion took hold, Marilhat fell victim to a compulsive perfectionism, beginning many new canvases only to abandon them in anger and frustration. As Gautier explained, Marilhat did not work from an ébauche but brought different parts of his canvas to completion before touching the rest of the picture, an unusual procedure that his mental illness exaggerated to a dramatic degree.25 In March 1847, overtaken by “melancholy” and prone to fits, Marilhat left Paris and retreated to his native Thiers, in the Auvergne. But the change in setting could not halt the delusions so common to syphilitic dementia, and in the end he quit painting altogether.

Gomot, whose 1884 biography of Marilhat draws on first hand reports, speaks of several instances where Marilhat’s mental illness and his Orientalism seemed unexpectedly to intersect. Marilhat’s family, worried by further signs of deterioration and thinking that a return to the studio might prove therapeutic for the artist, supplied him with materials and encouraged him to draw. To their amazement, they discovered that his abilities had entirely left him. Pencil and paper in hand, he set upon tracing stick figures as if in the margins of a schoolbook — the talent of the “Orientalist painter had been reduced to that of a child.” The artist was dead, Goumot explains, his “light extinguished,” and “his conception (idea) taken flight forever to the land of myrtles and oleander.”26 And from this moment, Gomot explains, Marilhat would speak with strange serenity of the time “when I was a painter” – quant j’étais peintre, Goumot underlining the phrase. Unable even to draw, Marilhat lost himself in memories of the Orient — the dromedaries and serpents in the desert, the “blue ibis in a melancholic pose on the banks of a river,” a “veiled woman passing like shadows,” – all that and more “lived in his spirit from the time when I was a painter.”27 The painter whose powers have left him withdraws into a child-like rehearsal of his earlier life. Dimly conscious of his own transformation, Marilhat calls upon the Orient as mnemonic refuge, allowing him to retreat in his mind where he could no longer travel in space.

The regressive cycle marched inexorably forward. In his last months Marilhat was overtaken by a determination to return to Paris from Thiers. Alarmed by the prospect, Marilhat’s family had him committed. Family and friends who visited the artist in the weeks before his death in September 1847 found he barely recognized them, and for that matter had little sense of his former self. But the blow to his pride held to have triggered his decline clung to him in the form of a compulsive re-enactment. And also to cling to him was his Orientalist dream, only now in the form of a child’s nightmare. As Goumot explained, the painter spent his last days compulsively drawing the outline of the Légion d’honneur on the walls of his room at asylum. When friends spoke to him of Egypt, in an effort to “pluck the strings of his memory,” Marilhat’s mumbled replies were incoherent — except for a phrase, now uttered in fear: “the camels, the camels!”28

Other versions of a quest derailed populate the corpus of Orientalist artistic biography. The sun, for example, could not only redeem but disable. Its regenerative power could go awry, consuming the painter from within. Alfred Dehodencq, who made multiple trips to Morocco in the 1840s and 1850s, would be described as suffering from a withdrawal of illumination that distorted his painting before sending him to the grave. We owe our account of Dehodencq to philosopher Gabriel Séailles, whose texts on Leonardo da Vinci, Eugène Carrière, and other topics once attracted wide readership. Séailles spoke of the dissatisfaction that gradually overtook Dehodencq upon his return to Paris, signaled in his inability to complete his paintings, in their destruction at his own hands, and in the introduction of exaggerated and unnatural light effects. Haunted by the memory of transcendence past, the sun that had fueled his enterprise now drove him into decline: “he could see nothing but what shone inside him. Did his tired eyes lose a feeling for sense of nuance? Were they satisfied with nothing but dazzling light?” In his last years, Séailles adds, Dehodencq brought to his painting a jarring intensity of illumination: he wanted “full-on light . . . direct, immediate impact — force without artifice, without resort to contrasts, an explosion of pure colors at their highest pitch.”29 Unconfirmed reports claim the sixty-year-old Dehodencq took his own life, although Séailles himself is silent on the topic, attributing his death to the painter catching a cold after the funeral of a friend. Regardless of the actual circumstances, at the very least we may say the sun tracks Dehodencq’s decline, luring him into a search for false transcendence. Where once the sun had rejuvenated the artist, its toxic residue now claimed him as victim.

Fiction and artistic biography overlap in the case of Naz de Coriolis, the Orientalist painter whose career the Goncourts recount in Manette Salomon. Following his return from Asia Minor, Coriolis becomes lover to his model Manette. Their union goes awry as Manette, a Jew, gradually isolates Coriolis in a Semitic domestic sphere he neither controls nor understands. The novel ends not with Coriolis dying but with his marrying Manette. But it’s worth emphasizing that his artistic decline, like that of Dehodencq, takes an Orientalist turn, Coriolis succumbing to an optical disorder that appears to “deregulate” and “trouble” his eyesight, and creating an insatiable desire for light. Paintings by the old masters that he once admired seemed too dark: “of light, he could find nothing but the pale memory. Something seemed to be missing in the encounter with these immortal canvases: the sun.”30 Coriolis now works only in the brightest light of day, overcompensating for the seeming darkness around him. His mental deposits of light-filled transcendence proved impossible to stabilize and control, distorting his paintings and tilting him into decline.

Redemption in the Studio

A passing detail concerning Chassériau’s funeral, cited by Gautier 1856, opens a window onto yet another elegiac theme – the painter united with his art from the grave. Gautier spoke of spotting a mysterious Arab man in a great black cape following the Chassériau’s funeral cortege with “Oriental gravity,” reading verses from the Koran, sprinkling water on his coffin, and adorning the painter’s mortuary chapel with a yellow wreath.31 The Luxembourg’s curator Léonce Bénédite, in a manuscript on Chassériau left unfinished at Bénédite’s death in 1925, reported finding a note in Chassériau’s estate that seventy francs should be given to “the Arab,” leading Bénédite to conclude that this mysterious mourner must have been a North African native whom Chassériau employed as model. Certainly this was a reasonable speculation, although the precise circumstances surrounding this mysterious figure are impossible to determine with certainty. But more important is the fact Gautier tells the story in the first place, and that Bénédite takes it up in turn. This mysterious “Arab” who performs rituals at Chassériau’s tomb is for Gautier more than a model. He is the living agent of Chassériau’s Orientalism, at once impenetrable and yet rendering honors to Chassériau for being represented in the first place – indeed not just rendering honors but, as we might put it, interpellated as subject on Orientalist terms. His model, the Orient “itself” – most of all he is the subject that Chassériau sets out to portray, now come alive to mourn his maker. The idea might seem farfetched, were it not that a memorial to another fallen Orientalist would propose exactly that.

For the lofty character of the Orientalist painter’s final journey, for the realization that his voyage into the sun was merely a rehearsal for a moment of transcendence revealed only on the other side of a one-way journey, and for the possibility such a redemptive metaphorics might be tasked with still more intimate work, look no further than Gustave Guillaumet. Today the painter’s fame rests principally on his Desert of 1868, a spectacular panorama that unites the sun, the desert, and a barely visible caravan in an exalted meditation on humanity’s struggle for existence in the face of the sun’s crushing power. Multiple additional trips to Algeria saw Guillaumet retreat from the grandiloquence of his Desert in favor a more Impressionist-style, observational project. Guillaumet’s Laghouat of 1879 and other paintings from this era established him as the leading French interpreter of the Algerian landscape and its local population, his urban scenes seeming to breathe with a sense of terrestrial exhalation nurtured by the sun’s animating embrace.

Of modest origins, success at the Salon brought Guillaumet substantial wealth and the promise of still greater success, promise cut short by his death in 1887 at the age of forty-seven. Twenty minutes before he passed, his biographer reports, Guillaumet was seized by a vision. At last free of pain, his features took on ecstatic expression: “alone with his soul at eternity’s gate,” all of a sudden his face was “transfigured”:

A vision came to him; the abundance of light to which he had dedicated his life reassembled before his eyes like a dazzling Grebe; it was the glory, undoubtedly, it was the goodbye to the sun, that, in this last moment, he believed he saw shining brightly. He stretched forth his arms, and in an attitude of ineffable admiration, he said these words, the last he would ever pronounce: “What gold! What gold! How beautiful it is! What golden palms!”32

Whether these were truly Guillaumet’s last words, and whether he truly died minutes later still with “a smile on his face” is impossible to verify. But verification is beside the point in the face of a deathbed discovery that rewrote Guillaumet’s worldly enterprise as a search for transcendence all along. His quest for the sun the sun was transformed in death, redeeming the painter in spirit as it had sustained his vocation. Bidding the sun goodbye, he welcomes its true face the figure of his future glory. The golden palms of posterity mark his passage into eternal life.

The story neither ends there nor begins there, however. As turns out, the circumstances behind Guillaumet’s demise were scarcely exalted. French papers spoke hesitatingly about the scandal, but the New York Times did not hold back, explaining that Guillaumet apparently shot himself in the chest following a quarrel with his mistress, “a lady who was his senior by many years.” What happened to the mistress in the hours that followed is never made clear, but we learn that his wife along with her son retrieved the mortally wounded artist and had him brought, at his request, to his studio, so that he could be surrounded by his sketches of Algeria “for the last time.”33 Eight days passed before Guillaumet succumbed, long enough for his physicians to regain hope he might survive the trauma; and long enough for the painter to reconcile with his wife, Guillaumet proposing they return to Lhagouat and other sites in Algeria, at once the setting for his art and for the renewal of their vows. The painter’s devotion to his art and his domestic sphere were now united in perfect if tragic identity, as if these historic antimonies could only be recalibrated at death’s door: “’if I get out of this,’ he told his wife, ‘we will return to Lhagouat. Do you remember how well I was working?… I have never worked so well as when I was with you…’” By day six Guillaumet had deteriorated, however. By the next day everyone knew the end was near.

Neither the manner of Guillaumet’s death nor a redemptive metaphorics of light appear to figure in Louis-Ernest Barrias’s magnificent monument to Guillaumet, unveiled in 1890 at Montparnasse Cemetery, and where it remains to this day. The sculpture saw enormous success, although countless reductions in bronze and other materials have served to obscure the commemorative circumstances initially attached to its making. The installation at Montparnasse features a Young Woman of Bou Saâda sitting on the monument, along with a medallion portrait of Guillaumet, also by Barrias, set on its base, together with the titles of Guillaumet’s pictures inscribed in the stone behind. The seated figure was in fact a variant Barrias’s Spinner of Megara, sent up from Rome for the Salon of 1870 while he was still a pensionnaire at the Villa Medici. Reworking the figure for Guillaumet’s tomb, Barrias changes the position of the girl’s hands, so that she now drops flowers on his grave rather than spins. More generally, he “orientalizes her,” switching out the Spinner’s Greek features, hair, and cloak for a melancholy muse with North African features, Algerian dress, a North African rug, and native Algerian flowers that she drops one by one on his Guillaumet’s tomb.

Barrias’s young flower girl also recalls female figures from Guillaumet’s own painting, for example his Weavers at Bou Saâda, exhibited in 1885 and again at a retrospective following his death. Whether it was this picture or similar interior subjects that Barrias had in mind we cannot say, but the notion that the girl derived from Guillaumet’s own painting was central to the conceit Barrias put in place, and was commonly described as exactly that. Charles Bigot, for one, made the point, noting that the features and attitude of this “young woman of Kabyla” owed nothing to Greece. Rather, she was “just the kind of girl Guillaumet frequently painted, either sowing or sitting at home, going to get to water or returning with it.” Indeed she “personified” Guillaumet’s oeuvre, Bigot explained, and surely Guillaumet himself would have wanted “no other image for his tomb.”34 The trope reaches back to Pygmalion, now reborn as a naturalist fantasy in a tragic key. The painter’s muse comes to life in the form of his model, only this muse is not the painter’s lover but his mourner. Nor in fact is she his model in the traditional sense, since Guillaumet was held not to employ models but native girls unaccustomed to posing. In short, and like the “Arab” who trailed Chassériau’s tomb, the young woman who mourns Guillaumet is a figure for the “real Orient” — truly an effect of his naturalist discourse, and yet seemingly offered up by nature itself.

A posthumous retrospective at the École des Beaux-arts offered critics the opportunity to revisit Guillaumet’s Spinners of Bou Saada, and more generally to take stock of the painter’s career and its sudden conclusion. For all their determination to remain silent on the circumstances of Guillaumet’s death, their readings worked to cement the urgent renewal of vows that followed the bizarre conduct that had brought him to his deathbed. Guillaumet’s friend Durand-Gréville, writing in L’Artiste, cites the Spinners of Bou Saada and others like it as evidence of a true “collaboration” between the artist and his spouse. Without her, Duran-Greville insists, Guillaumet would never have been able to secure models, still less overcome their nervous stares as he walked into the studio, not to mention their tendency simply to slip away.35 The peaceful, absorptive, and as it seemed timeless rituals that populate his Algerian subjects were wholly the fruit of a collaboration between husband and wife. Scarcely is it farfetched, under the circumstances, to imagine Barrias’s Young Woman of Bou Saada as re-inscribing on Guillaumet’s tomb the idealized union of art and domesticity that his violent quarrel so scandalously undermined. To be sure such a reading might seem scarcely open to verification. But certainly Barrias was sufficiently well-informed, and indeed sufficiently invested, to put such a message in place. Not only were he and Guillaumet friends, but Guillaumet had studied with Barrias’s brother, the painter Felix-Joseph Barrias (not an Orientalist, deceased in 1907 under circumstances unknown, but author of The Death of Chopin, painted in 1885 and in its day widely reproduced).

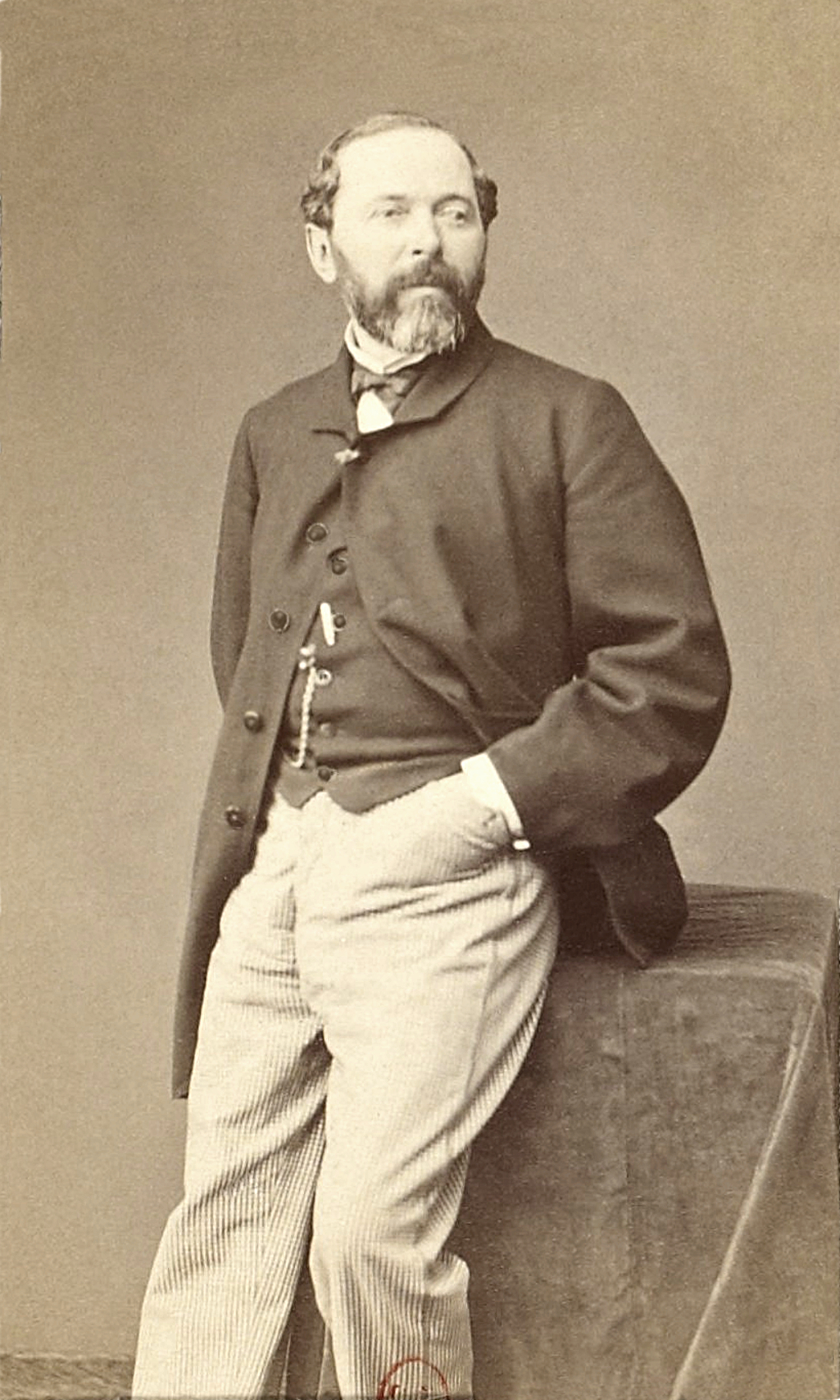

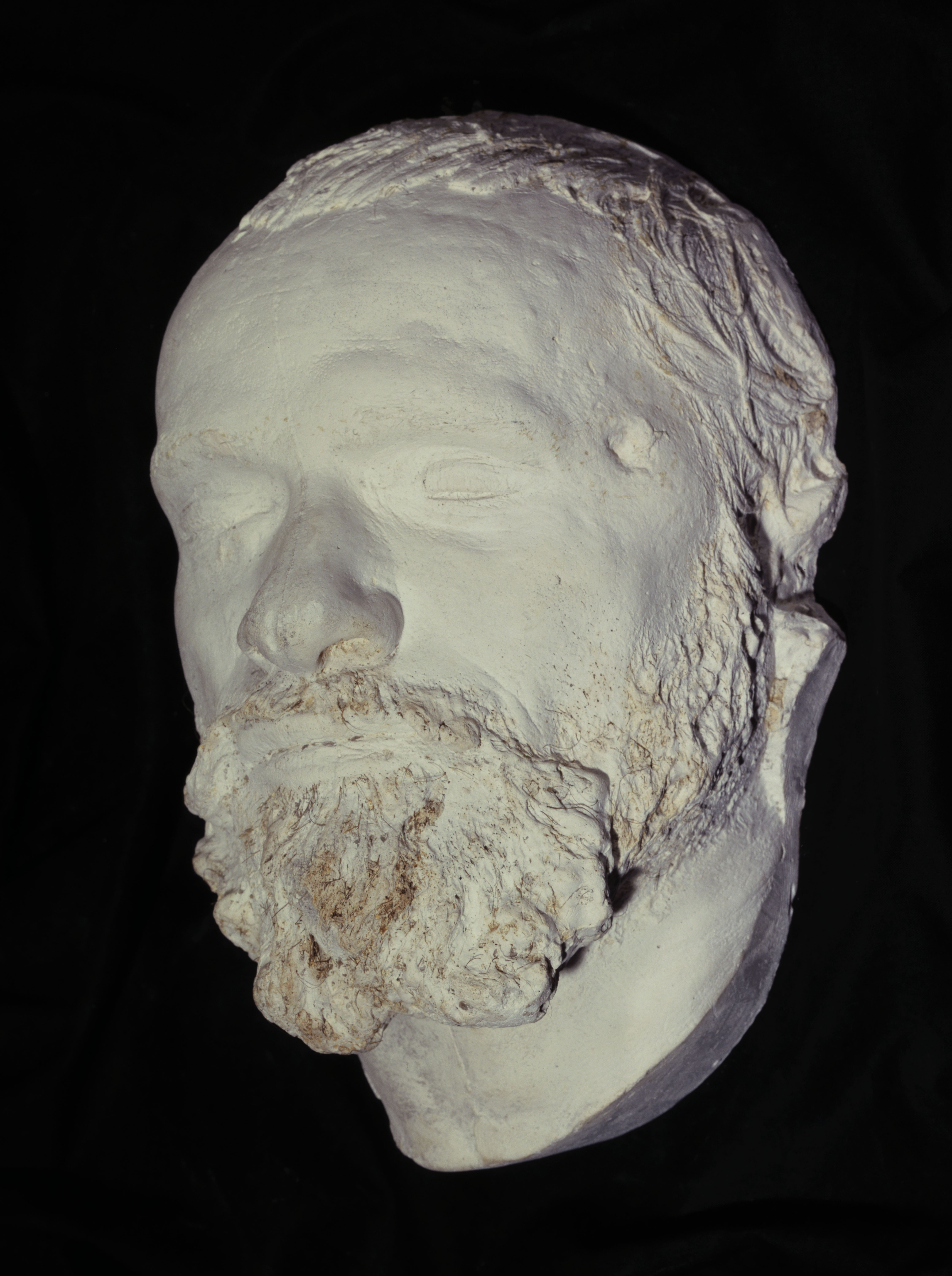

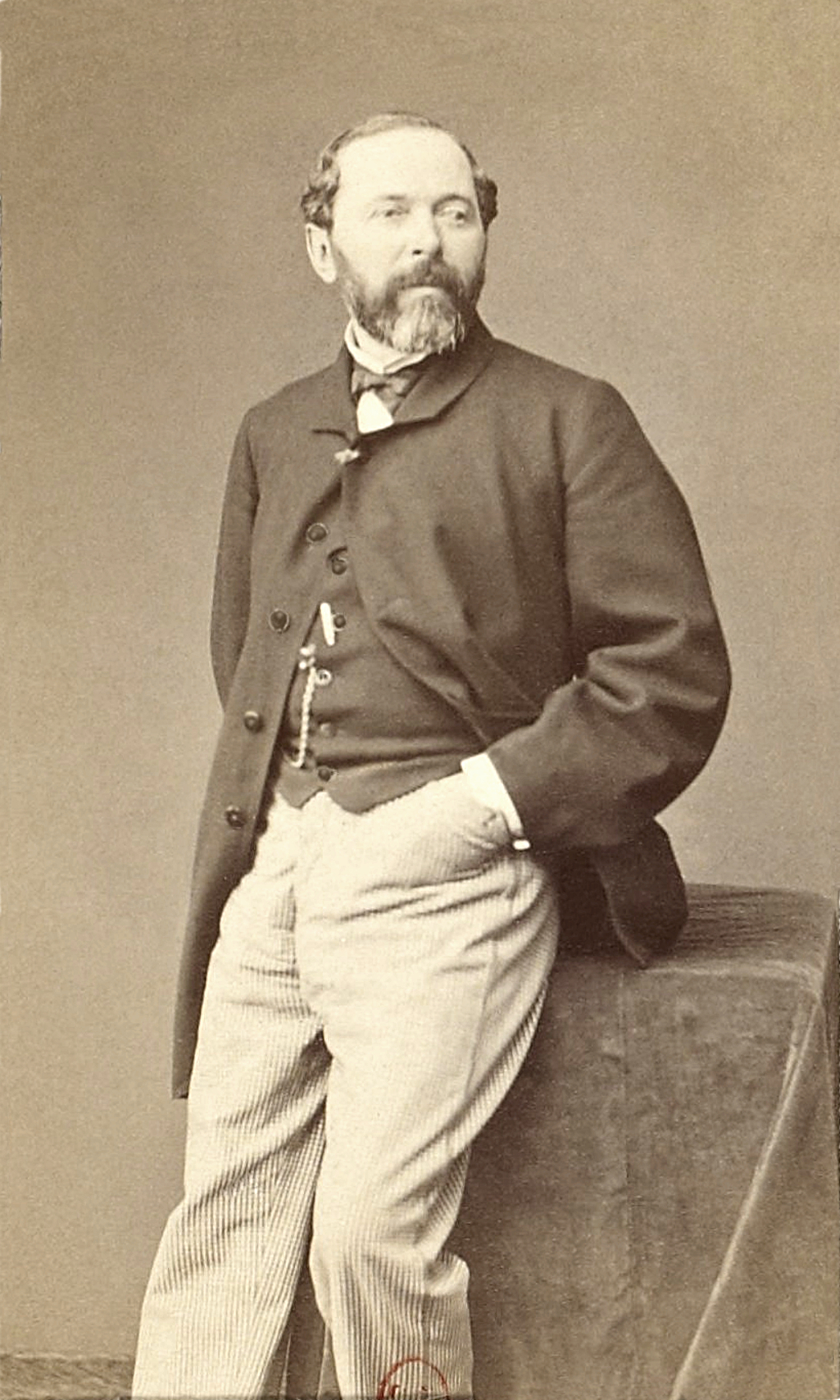

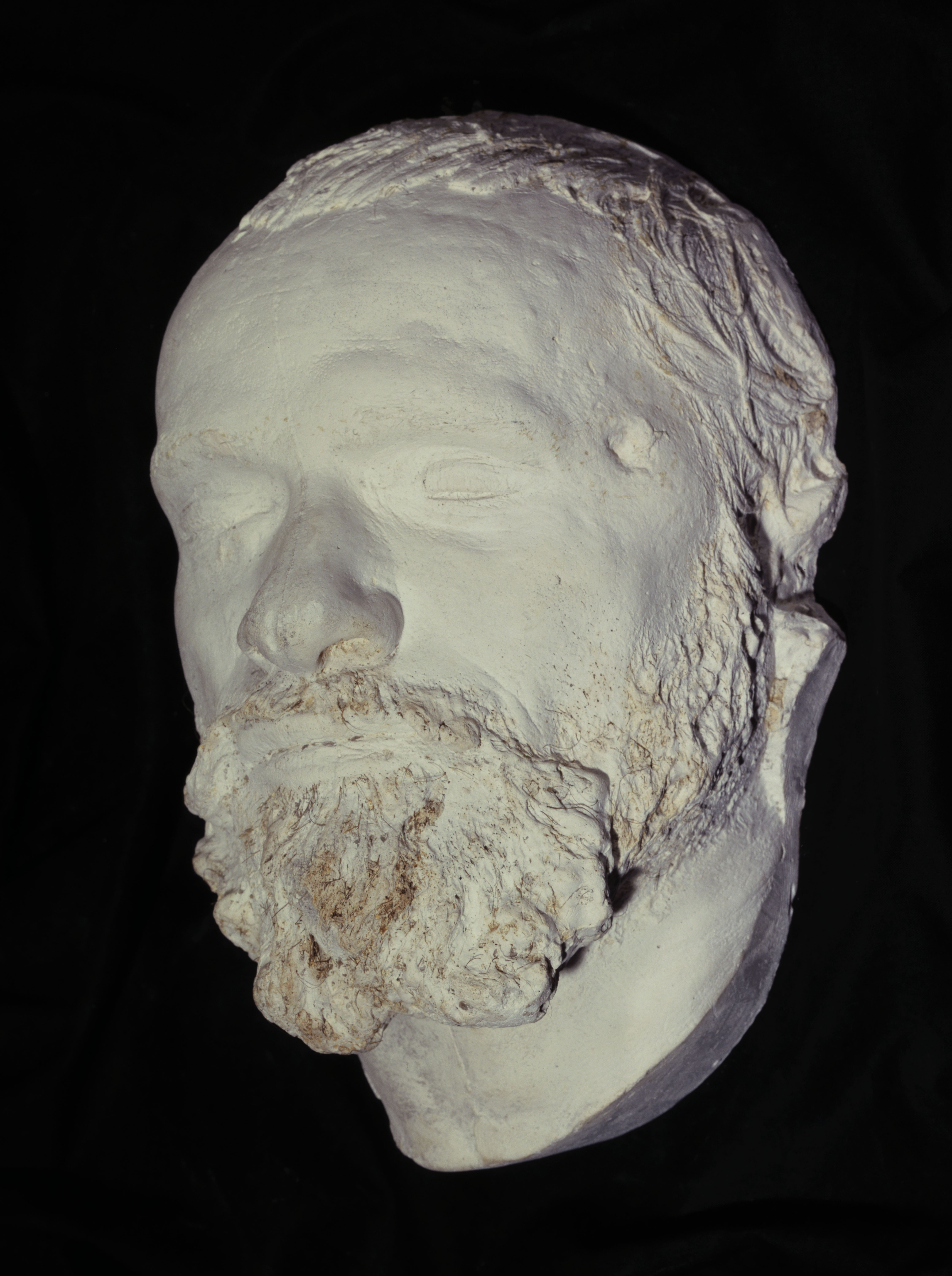

Orientalist artists died in ways like anyone else, but by virtue of their exotic trajectories they attracted to their deathbeds a rich metaphorics of mortality that the present pages have only begun to unpack. Suffice it to close with another example, as it happens another occasion that saw Barrias charged with commemorating a fallen friend. The scene united the work of mourning and representation, even as Barrias effaced the work of his hand in an effort to preserve the features dear to him. On January 27 1871, five days following Henri Regnault’s death at the Battle of Buzenval, Barrias together with Georges Clairin pulled a plaster mold from their dead friend’s face, following the delivery of his body to Père Lachaise. In the years ahead this intimate artifact was molded in plaster, cast in bronze, and widely photographed, allowing countless Frenchmen to reflect on the death of a painter destined, as it seemed, one day to lead the French school.36 The installation in 1900 of the original plaster at the Musée Carnavalet allowed still more viewers to view up close this effigy of the Prix de Rome painter who, returning to Paris from Tangier, joined the National Guard and was killed on his first day of combat. But between the entry wound on Regnault’s left temple and the smashed nose that gave him the features of “a Mongol,” to cite one critic’s phrase, what was called up even more than Regnault’s sun-lit dream was its sudden and definitive end, expressed for all to see in the path left by a bullet to the brain.

Notes

Mostly they died in ways like anyone else. The fifty-seven year old Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, who enthralled Paris audiences with suite of exotic genre and biblical subjects following a year in Asia Minor in 1829-1830, perished in August 1860 after being thrown by a horse, near his home in the forest of Fontainebleau.1 Léon Belly, whose Pilgrims Going to Mecca of 1861 remains one of the best-known Orientalist pictures of the nineteenth century, died in Paris in 1877 after a long and debilitating illness. The French art world was shaken by the news of this artist cut down at the age of fifty, but there was nothing Orientalist about the manner of his death, no reports of dramatic last words or studio deathbed scenes.2 We know even less about how the end came to Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouÿ, a student of Ingres and best known for his White Slave of 1888. His death in Paris in 1921 at the age of eighty-one attracted little attention, silence traceable in large part to a historic artistic reset that saw so many academic masters of the nineteenth century fall into obscurity. To repeat, Orientalist painters left the world under varied circumstances — violent, painful, peaceful, or in ways simply unknown, in other words just like anyone else. And yet the basic argument of this essay is that how Orientalists died is not only an empirical but discursive question. From this latter perspective, their manner of passing would be mediated across a rich poetics of mortality whose shape and texture these remarks explore.

Sometimes an Orientalist simply died a painter’s death. Nothing as emblematic or status-driven as Raphael dying after painting Christ’s face on his unfinished Transfiguration, or Leonardo da Vinci dying in the arms of Francis 1st, to cite two notable deathbed scenes, recounted by Vasari, that Romantic artists took up with gusto. Nevertheless, examples abound of nineteenth-century artists who died in a manner that in some measure evoked their artistic vocation. Take the case of Charles Gleyre, a Swiss painter working in Paris remembered today mostly for his Lost Illusions of 1843, a talismanic, Orientalizing scene of fatalistic disillusion. Three years in Greece, Egypt, and Syria in the mid-1830s saw Gleyre nearly succumb both to fever and severe ophthalmia, including ten months where he lay nearly blind in the vicinity of Khartoum.3 Gleyre’s experience in the Middle East was said to have left its mark on the famously grave and taciturn artist. The end, however, did not come until May 1874, when the sixty-eight year old artist collapsed while viewing an exhibition in support of the lost provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, at the Palais Bourbon.

His biographer Charles Clément, rushing to Gleyre’s house to view his friend’s body, noted that his “tired features, so often wracked with pain,” seem “relaxed.” The painter’s face bore “an extraordinary expression of calm, peace, and serenity.”4 Note that Clément is anxious to stress the precise circumstances surrounding Gleyre’s last moments: the exhibition on behalf of the lost provinces, the gallery where he fell, the fact that he was accompanied by a student, walking with deference “a few steps behind.” He also noted the time of day–precisely 11:50, Clément explained, Gleyre arriving in time still to qualify for half-price admission. Here as elsewhere, the broadly positivist protocols of nineteenth-century biography did not tolerate the kind of strategic fictions that populate Vasari’s deathbed scenes. And yet it’s tempting to treat this recitation of details as embedding a poetics of its own. The site of Gleyre’s death, to be sure–to drop dead in a museum, surely that is a painter’s death; note, too, the image of the respectful student following a few steps behind. And let us not omit the allusion to Gleyre’s parsimoniousness, which Clément cites to pinpoint the time of death, but which also serves as ironic counterpoint to the catastrophe shortly to unfold. Finally note the narrative takes an Orientalist turn, Clément evoking the sense of serenity on Gleyre’s features following his release. Clément imagines Gleyre at last free of physical torments that dogged him from his months in Egypt, torments that nurtured his fatalistic disposition and marked him to the grave.

Eugène Fromentin did not die an “Orientalist” death either, but as with Gleyre, his biographers could not resist bringing Fromentin’s experience in North Africa into play. Fromentin’s Street at Laghouat from the Salon of 1859 emerged as a touchstone of Orientalist art criticism, and to this day his journals recounting his travels to Algeria stands today as among the most accomplished examples of the genre. The fifty-six year old Fromentin died in 1876 in his hometown outside La Rochelle, on the Atlantic coast. He only recently had failed (again) to secure a seat at the Institut, although in literature rather than the section for painters. The prospects of a chair in painting, Fromentin knew, were slim — a career consisting of genre paintings or mere tableaux de circonstance would never qualify him for his profession’s highest honor. Fromentin’s biographers, for their part, evoked a sense of Orientalist irony. Hence the phrase of Emile Montégut, who cited an Arab proverb as he spoke of Fromentin succumbing just as he was in the full maturity of his powers, and on the point of being properly recognized: “When the house is built, death comes and slams the door,” Montégut observes, explaining that certainly Fromentin knew this “fatalistic” proverb, in which seemed “condensed” all the wisdom of the Orient. Surely Fromentin’s “sudden disappearance,” Montégut adds, so “unexpected,” offered a “lugubrious” and alas “all too justified” demonstration of the proverb’s veracity.5

The idea that Fromentin’s death offered an ironic fulfillment of the lessons learned on his travels to Algeria operates as more than rhetorical conceit. We find many similar statements across the corpus of Orientalist artistic biography, as friends and biographers brought to their obituaries and memorial essays a poetics of endings that entwined art and death along an Orientalist axis. In some cases critics improvised with a light touch, Montégut’s phrase about Fromentin offering a case in point. But in other cases the figuration was more ambitious, encompassing for example a painter’s last words, the manner of his death, the kind of memorial made for him, or for that matter who turned up at his funeral. And as the example of Gleyre suggests, the broadly positivist protocols of nineteenth-century historical writing were scarcely immune from such figuration and indeed might be said to have offered this poetics new force and grip. How an Orientalist painter died, to repeat, was not just an empirical but a discursive question, and we must treat such end of life stories as a rich, aspirational, and broadly vocational mythology, at once varied and malleable as per the circumstances of the case, even as certain themes and motifs recur in a manner open to historical and rhetorical analysis.

From Leonardo to Raphael and many others, accounts of artists’ deaths by Vasari and his successors offer an important precedent for these concerns. Across painting, biography, and illustration, artists, critics, and illustrators rewrote the biographies of the old masters through the filter of their own aesthetic and critical positions. We generally treat pictures depicting the last moments of Leonardo, Michelangelo, Titian, and Raphael as doing strategic work, nineteenth-century artists seizing on their presumed ancestors as historical aliases and fashioning a mediated image of the present. And yet the topic of how nineteenth-century artists died remains by and large unexplored. Certainly it might seem hard to elicit from nineteenth-century data the topoi, mythical residue, or “biographical cells” that Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz explored in stories told about artists from antiquity to the Renaissance.6 We commonly associate nineteenth-century life writing with the emergence of positivist evidentiary protocols inhospitable to the kind of mythic formulae projected onto the old masters. The catalogue, the retrospective, the artist’s correspondance, and other instruments of modern artistic biography were generally hostile to figurative play. And yet the emergence of this historiographical edifice should not obscure the sheer fertility of meaning-making associated with artists’ death, meaning-making operating not just side by side but embedded within the edifice itself. That poetics, in short, was sometimes all the more powerful since it took the form of simple description and in this sense did not seem like mythmaking at all.

Only rarely did the deaths of nineteenth-century artists qualify for visual illustration, still less were they staged in drama or fiction. The Death of Gericault, painted in 1824 by a member of his circle, offers an important exception in this regard, notable in part because of its association with a death mask of the Gericault that proved crucial to the legend of the artist as it took shape. Alexandre Decamps painted The Suicide in 1835, inspired it was held by the suicide earlier that year of Léopold Robert. Alexandre Menjaud completed Girodet Bids Farewell to his Studio in 1826 shortly after the master’s death, but despite these examples such visual evocations are rare. By and large, for the nineteenth century these practices of figuration lie on textual terrain, from formal artistic biographies to obituary notices and casual recollections circulated in the press. Inscribed within and sometimes working against the secular protocols of life-writing that eventually came to dominate such writing system wide, they open a revealing window onto the psychologically and historically configured imperatives that shaped and structured an artist’s vocation, from their studios to their deathbeds.

Let me make two additional points before developing a series of examples in greater detail. Whether the deaths of Orientalist artists inspired a more varied or elaborate poetics than, say, the deaths of landscape or history painters in the nineteenth century, is an important question that lies beyond the compass of the present study. “The Sun is God,” Turner is said to have uttered on his deathbed – arguably the most famous last words by any artist (the tale traceable to Ruskin, although whether Turner said them is doubtful). But by way of a preliminary hypothesis, I want to argue that a combination of historical, geopolitical, and cultural factors combined to give Orientalist narratives of mortality singularly deep purchase. Many recent accounts of nineteenth-century Orientalist painting emphasize its invented, idealized, and indeed ideological character – ideological work, as the argument goes, that operates invisibly thanks to that painting’s typically realist idiom. Whether or not we sign on to the charge, at the very least we may say that precisely Orientalist’s invented and escapist character offered a ready platform for end-of-life narratives to take flight. Orientalism perhaps most of all among nineteenth-century art movements nurtured an elegiac poetics of mortality, loss and exile that left painter and career, life and art, mysteriously and sometimes fatally – like “The Orient” itself — intertwined.

Finally, I want to make the additional point that for all its richly imaginative character, this poetics was not simply born from studio voyages. It was fruit of the broadly naturalist climate of the mid- and later-nineteenth century, as Western artists travelled to North Africa and the Middle East, and the profession of the painter-traveler took shape. Each of the artists discussed in this essay actually journeyed to “The Orient,” several of them on multiple occasions and two (Fromentin and Gustave Guillaumet) leaving behind important literary monuments. Following in the tracks laid by colonial expansion, painters and illustrators established commercially successful practices that highlighted the first-hand, observational basis of their exotic representations. Needless to say, artists also mined the classic tropes that in the Western imagination defined the region’s climate and geography — the desert, the caravan, and the oasis, among others. But it was the reality of such journeys that gave this poetics special feeling. Such travel, as it seemed, marked a painter’s eyes, body, speech, and affect — in short how painters lived and how they died.

Death Abroad

The risks were real. The Scottish born history painter David Wilkie died at age fifty-six outside Gibraltar aboard the steamer SS Oriental in June 1841, en route home from Syria and Constantinople. The exact cause of death is uncertain, but the surgeon aboard the Oriental, who took careful notes as Wilkie deteriorated, writes that the artist came aboard in Alexandria already sick, and that his condition deteriorated rapidly following the consumption of fruit and iced lemonade purchased during a stop in Malta. The Spectator reports that passengers on the steamship lobbied the captain to bring Wilkie’s body ashore, but the Governor at Gibraltar refused permission and the artist was buried at sea that evening at 8:30 pm, just before sunset.7

The availability of the surgeon’s notes helped assure that Wilkie’s biographers would confine themselves to clinical descriptions of his final hours. His death resonated in British visual culture for decades after, however, thanks in large part to his friend J. M. W. Turner, who made Wilkie’s burial at sea the subject of one of his most famous pictures. “The midnight torch gleam’d, o’er the steamer’s side,” explained Turner in The Fallacies of Hope, when his Peace-Burial at Sea was first exhibited in 1842 (along side War, The Exile and the Rock Limpet, a pendant also themed on the topic of exile, and featuring Napoleon on the Island of St. Helena). Ruskin, as it happens, was disparaging about Turner’s use of black, and many other critics found fault in Turner’s disinclination to describe the event with exacting accuracy. But eventually it became one of the artist’s best-known pictures, routinely inspiring more sympathetic viewers to spiritual heights. Turner, explained Ralph Nicolson Wornum, keeper of the National Gallery, in account of the picture published next to a mezzotint by Alfred-Louis Brunet-Debaines, was not the kind of artist to be “tested by realism.”

Nor might we add was Turner tested by the facts of the case. The burial time of 8:30pm was widely noted, but perhaps in an effort to motivate the great contrast of light and dark that so puzzled the picture’s first viewers and continues to puzzle scholars into the present day (Paulson goes as far as to suggest the great mass of black on the ship is in fact a London stagecoach, an allusion to the burial at home that was denied to Wilkie), Turner sets the hour at midnight, as if to dramatize the symbolic darkness of the occasion by a striking contrast of light and dark. And while the light is torchlight, John Mollet described the picture’s effect of hyper-natural illumination as almost “mystical” in character — a “great flood of crimson light that seems to consecrate the temporary chapel of the waist of the ship, and the coffin’s plunge into the illuminated wave of crimson flood of light.”8 Of course Mollet was right – transcendent effects of light dominate Turner’s art through and through. But on this occasion we may say that Turner adapts that commitment to a metaphorics of illumination already inscribed in Orientalist painting and criticism, a claim we will have occasion to revisit in the remarks ahead.

Another example, in this case an artist who perished in the field. Clément Boulanger, a pupil of Ingres, saw success at the Salon in the 1820s and 1830s before signing up in 1841 as recorder to an archeological expedition led by Charles Texier to the ancient city of Magnesia, in the Meander Valley. As Alexandre Dumas recalled in his recollections of the artist, in September 1842 the group was at work excavating a magnificent temple to Diana, destroyed in an earthquake and now partially under water. Unwisely seeking to complete a sketch “in the full heat of the midday sun,” Boulanger succumbed to a “one of those bouts of sunstroke, so dangerous in the Orient.” Achmet Bey, the Governor, sent his carriage and attendants “for the use of the sick man,” but too late, and the only medical treatment available was from “bad Greek doctors, like those that killed Byron.” A report in the Smyrna Journal, reprinted in the French press, adds that upon being taken ill, native workers at the site were sent off to fish for leaches (Byron was also bled), but the physician in charge of treatment was not a Greek native but rather was attached to their ship, L’Expéditive.9 Falling into a delirium, Dumas continues, Boulanger was set in a hammock in a nearby mosque and died within five days, “singing and laughing” but “not doubting he was dying.”10

The funeral of this thirty-seven year old painter was prestigious. Boulanger’s body was transported to Scala Nova (present day Ku?adas? in Turkey) by horse, attended by “eight Greeks” and a dozen sailors from L’Expeditive. Reports in the French and English press add that that the ceremony drew local diplomats as well as a contingent of clergy, not to mention all the Christian residents of the city, who gathered to meet the cortege upon its arrival. Dumas claimed that no less than three thousand people trailed Boulanger’s coffin by the time it arrived at the French legation in Constantinople – quite wrong, since the body never travelled there. But we do know that in a show of patriotic solidarity, French houses and commercial institutions adorned their facades with funeral banners and flags, as did ships offshore. Other locals, too, it was reported, would pay their respects to fallen artist. To be sure, the stakes for these communities differed, sited as they were on hierarchically distinct positions on the “imaginative geography” (Said’s term) that mapped Boulanger’s path to the tomb. But in each case, the honors shown an artist charged with retrieving a community’s lost or forgotten history operates as a legitimating topos of imperial culture, just that homage seeming to fuel a sense of solidarity on the ground, and reported up to readers back home.

This cultural work of mourning operates not only over space but over time, the deaths of Boulanger and Wilkie sending out a lingering after-image of the painter-traveller’s journey gone awry. “Poor Clément Boulanger,” writes Louis Gonse in the Gazette des beaux-arts in 1874, upon encountering one of his pictures in Lille. “He rests now, unknown, in the cloister of a Greek church in Smyrna, where probably no traveller thinks of going to render him pious homage.”11 In fact this was not quite right — Gonse’s lament for Boulanger’s forgotten tomb was enabled in part by the fact it was not forgotten, but rather formed part of an elegiac, Orientalist tour. Travelling to Constantinople a decade later after Boulanger’s death, Théophile Gautier reports encountering a plaque honoring Boulanger in the exterior cloister the Greek Church near the marketplace in Smyrna. “The Tomb of a compatriot in a foreign land,” confessed Gautier, has always something of a sadness in its associations, be it from an unacknowledged selfishness of humanity, or from a vague impression that the foreign soil presses more heavily upon the ashes which it covers.”12 Note the chance character of the encounter. It may well be that Gautier had been informed of the memorial, or that his guide took him to see it. But in the narrative as he stages it, serendipity leads him to explore a mysterious cloister in a provincial town, only to discover the faded trace of another who preceded him. “Foreign soil,” Gautier explains, seemed to press “more heavily” on the fallen artist than burial in his native land, although of course what Gautier means is that it pressed more heavily on himself, his encounter with Boulanger’s ashes catalyzing traveller’s anxiety for home. Other travellers, too, in the years ahead, took note of the plaque and sent in reports for readers back home, including Adolphe Joanne and Emile Isambert in 1861, and Emile Bourquelot in 1886.13 A mournful poetics of the forgotten exile rested on the possibility of sometimes being remembered. For Boulanger this took the form of an actual site on a cultural and archeological tour. But the principle obtains for Wilkie as well, British travellers steaming past Gibraltar taking note of the approximate location where the SS Oriental consigned their compatriot to the deep.

Sacrifice and Representation

Another death in the field saw friends rally round a painter in an effort to inscribe his fatal pilgrimage in the canon of British art. Affiliated with the Pre-Raphaelite circle, Thomas Seddon died of in November 1856, at the age of thirty-five, while on his second visit to Cairo. Three years earlier the born-again Christian had accompanied Holman Hunt on a voyage to Egypt and subsequently Jerusalem, pitching a tent in the surrounding hills and studying its sites. From this campaign Seddon completed what is generally regarded as his masterpiece, Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from the Hill of Evil Counsel, whose striking topographical and geological accuracy inscribes a tri-partite allegory of resurrection readily accessible to a viewer informed by similar Christian fervor. Commercial success cemented Seddon’s conviction he should return to the Middle East, again with the idea of undertaking sacred subjects, and to which he proposed to bring a new level of documentary veracity based on first hand-observation of the region’s topography, flora, and geology. The motivation for this disciplined program was less artistic than educational – precisely by sacrificing, as it seemed, fatuous claims to originality, Seddon could present the Holy Land to audiences back home for their religious benefit: “He wished to present to those who could not visit it an accurate record, not a fancy view, of the very ground our Savior so often trod,” explained Seddon’s brother, in a note to The Atheneum in 1879.14 All of this is to say that Seddon’s embrace of unmediated realism was less an aesthetic position than a moral obligation. His conviction he must forego anything “fancy” constituted a willing and deliberate act of artistic selflessness.

Within a few weeks of his arrival in Cairo, Seddon came down sick — “thrown for a sharp curb,” he wrote his wife, indeed perhaps “punished” for “a want of attention to His Sabbath,” Seddon confessing to having walked the streets and alleys after church on Sunday, rather than returning home to rest.15 The days ahead offered an uncanny mirror-reversed image of an earlier experience: during his first trip to Egypt, Seddon had nursed a fellow traveller known only as Nicholson, moving him from Cairo to the Pyramids as he declined and finally died. But on this occasion, as commentators rued following a memoir on Seddon published by the artist’s brother, it fell to a physician and missionary in the Cairo community of expatriates to take this obligation on: “and when, after no long period, he himself lay on his deathbed, in the same land of strangers, it is touching to know that a friend as devoted was raised up to him, and the cup of cold water he had given to another held to his own parched lips by a gentle Christian hand.”16 A mere four weeks following his arrival Seddon was dead, felled by dysentery in all likelihood acquired on the passage from Marseilles.

Needless to say, Seddon’s death struck friends and admirers hard, many of them yielding to magical thinking in an effort to assign agency where there was none. Look no further in this regard that Seddon himself, whom as friends report, had recently confessed to intimations of mortality. He neither “expected nor desired,” Seddon’s brother recalled, “to be long lived.” Indeed it “really seemed as if he felt a presentiment of his death, and was studiously making preparation for it.” Seddon’s circle of friends found comfort in this notion, Seddon’s serenity and good nature in the face of these intimations helping to lift the pall cast by his death and mobilizing their commemorative work in turn. The tragic outcome of his second tour would be assimilated to a divinely inspired master plan. The death of this artist in the field was not simply an occupational hazard, but the highest expression of his devotion and even his destiny. The quest for first-hand observation that underwrote his journey was a spiritual quest through and through, an artistic version of an ethics of sacrifice that found its highest expression in Seddon’s early passage into eternal life.

All this and more informed the attitudes of his friends when they gathered at the house of Ford Maddox Brown for the purpose of preserving Seddon’s memory in the annals of British art. Together with Holman Hunt, John Ruskin, and others in the Pre-Raphaelite circle, they launched a subscription campaign to acquire Seddon’s Jerusalem for the nation, in the end purchasing the picture for six hundred pounds and offering it to the National Gallery. This, too, as it seemed, was part of Seddon’s master plan. His brother reports that he had proposed to let the picture go at a low price to a collector, with the proviso it be offered to the Gallery after his death; and that in still another scheme, Seddon had planned to present a large copy of the picture for a “public institution,” so that others may have “a correct representation of the very places that were so often trod by our Redeemer during His sojourn on earth.”17

For an account of Seddon’s aesthetics self-effacement, look no further than Ruskin, who praised Seddon’s Holy Land subjects for their absence of art. It was Seddon’s presence there, Ruskin explained, and the mortal risks that presence entailed, that assured the truthfulness and sincerity of his pictures, and hence his seeming invisibility at the scene of representation. Seddon’s landscapes, Ruskin explained, were “the first” to unite “perfect artistical with topographical accuracy.” The first to be “directed, with stern self-restraint, to no other purpose than to giving those who cannot travel, trustworthy knowledge of the scenes which ought to be most interesting to them.” All previous efforts at truth in this area had been “more or less subordinate to pictorial or dramatic effect,” in other words what Seddon’s brother had termed “fancy.” For Seddon anything fancy was absent. His “primal object,” Ruskin insists, was to “place the spectator, as far as art can do it, in the scene represented, and to give him the perfect sensation of its reality, wholly unmodified by the artist’s execution.”18 It is hard to imagine a fuller statement of an of artful self-sacrifice – artful because the guarantor of Seddon’s invisibility was the fact he was there, his presence assuring his viewers they were seeing the truth even as he relinquished all claims for this art and put his own life at risk. Seddon’s humble dream of unmediated realism on another’s behalf stands as artistic counterpart to his own readiness to follow the path of Christ, literally and figuratively to the Promised Land. Surrendering his art for the sake of a truthful representation, Seddon’s death was not simply a risk associated with his voyage but in a sense its fulfillment — hence Ruskin, as he called on the public to throw itself behind “the sacrifice of the life of a man of genius to the serviceable veracity of his art.”19

The Sun and Death

“Light!” exclaimed Henri Regnault as he fell in January 1871, his “last cry” evoking the immersive, sun-filled dream that took him from Paris to Rome, Madrid, Granada, and finally Tangier.20 Doubtless it is farfetched to imagine the famous hero of the Franco-Prussian War, killed outside Paris on a cold, gray afternoon, to have shouted out the word encapsulating his journey to “the land of the sun” — not least of all because no one saw him fall. But the tale, sent around three decades later by Gabriel Hanotaux, a leading historian and diplomat, speaks to the currency of an Orientalist poetics of illumination that so colored Regnault’s memory that readers could imagine exactly that. For Regnault as for many others, a well-trodden metaphorics of light came utterly to saturate Orientalist art criticism and artistic biography, the sun seeming at once to illuminate their artistic path but also trail them to the grave.