You can watch the full event here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wqTfM56s4aA.

Introduction

Katherine Rader

The essays included in this symposium were written by the panelists for the event “Checking Your Privilege? Perspectives on the Politics of White Identity,” hosted by the Andrea Mitchell Center at the University of Pennsylvania in March 2021.1 In preparation for the panel, each panelist prepared a short essay addressing the question, “What kind of politics are enabled by the study of white identity and/or white privilege?” This notion has garnered significant attention from politicians, activists, and academics alike in the past half-century. Proponents argue that “checking” this privilege or reforming white identity (think: Peggy McIntosh and the Invisible Knapsack) is a necessary first step in dismantling structural racism. Critics of this position argue that this insistence on a shared white identity actually obscures the material basis of contemporary racism and hampers efforts to achieve meaningful racial equality. Ultimately, these arguments connect back to debates over identity politics and the utility of a politics or political analysis grounded in group demarcation.

The hope was that in focusing on the politics enabled by the study of white identity and white privilege, the panel might avoid the trap of the esoteric academic panel and engage a broader audience around the political question (at least in numbers we were somewhat successful here, with over 900 registrants to the event). The panelists invited to participate in this event represented these two broad perspectives on white identity and approached these questions from a variety of methodological, epistemological, and disciplinary perspectives. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva is a professor in sociology and African American Studies at Duke University and author of Racism without Racists: Color-blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America, which explores the ideology of “color-blind racism.” Ashley Jardina is an assistant professor of political science at Duke University and author of the 2019 book White Identity Politics, which offers empirical evidence of a discernible and politically significant white racial group identification. Hadass Silver is a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania and is currently writing a critical theory dissertation examining white privilege discourse and its connections to movements for racial and economic justice. Walter Benn Michaels is a professor in English at the University of Illinois at Chicago and author of The Trouble with Diversity, where he considers how the pervasive focus on diversity obscures issues of economic inequality.

The goal of the panel, as Jardina aptly put it, was to “step back from the minutiae of our research to consider not just the normative implications of group identities, but also to reflect on the social and political implications of studying the concept in the first place.” Unsurprisingly, one central political goal shared by all the panelists is to secure greater racial equality. In addition, three of the four papers (save Jardina’s) point to the necessity of a more economically redistributive version of democratic socialism for the realization of greater racial equality. But these shared goals did not occupy the majority of the discussion, rather it hinged on the question of whether the study of white identity could further or hinder racial equity and democratic socialism.

The first position, advanced by Bonilla-Silva and Jardina, is that issues of white identity and other racial divisions need to be addressed before other political projects can be pursued. Bonilla-Silva, invoking Charles Mills and Stuart Hall, argues that to attain a democratic socialist society, it is first necessary to confront and deconstruct racial divisions. In other words, the primary obstacles to realizing democratic socialism are racial divisions and animus.2 However, Bonilla-Silva does not lay the blame at the feet of fringe white nationalists—he argues that “nice white liberals” and those with even “marginal whiteness” materially benefit from the production of a white habitus and systemic racism. Further, Jardina contends that “racial identities are what members of marginalized groups use collectively to fight against an arbitrary distinction.” In other words, these identities have become necessary tools for fighting for racial equity. And crucially, both scholars maintain that subsuming issues of race into a broader pursuit of redistribution or equality would have a deleterious effect on struggles for racial justice.

Silver and Michaels, on the other hand, push back against the idea that racial reckoning in the mold of white identity and privilege discourse is a necessary first step. Rather, they argue that such a focus is, in fact, a detractor from a broader social-democratic agenda. Instead of working to advance shared goals, Silver argues that “implying that economic hardship primarily derives from the differential treatment of whites and nonwhites” ultimately “distracts from the systemic mechanisms that underlie material disparities.” Michaels attends closely to these material disparities—pointing out that these “material benefits” incurred by whiteness are not clear when considering the trajectory of economic inequality in the past half-century, when “the difference between rich people and the poor (of all races) has steadily increased, [the knapsack] redescribes that difference as the disparity between white and black.”

The panel discussion itself expanded on these key themes and questions from the audience attempted to probe further into the consequences of these identity politics debates for contemporary struggles on the left, including the Black Lives Matter movement and the Amazon unionization campaign in Bessemer, Alabama. While the discussion hardly resolved these sharp differences, it certainly shed light on this increasingly prominent debate over identity politics and the potential for racial and economic equality.

Notes

[tab: Jardina]

Ashley Jardina

In the 1970s, four scholars participated in a panel discussion for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. They were asked to address questions about the social and academic value of ethnic identity.1 In response, Orlando Patterson, a professor of sociology, wrote, “The particularistic and divisive social philosophy of pluralism is, in my mind, one of the most tragic intellectual developments of our time” (32). Taking a somewhat more sanguine perspective, University of Chicago sociologist Andrew Greeley lamented the lack of diversity within the academy and wrote, “The critical challenge is not to eliminate or reject ethnic identity—that is a self-defeating effort—but rather to understand how diversity and the tensions it engenders can be integrated into some form of unity” (25). In response, the Harvard sociologist and soon-to-be U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan told both Patterson and Greely, somewhat snidely, to get over themselves. They should instead, he argued, accept the world as it is, which for Moynihan meant acknowledging that, “For too long, world affairs have been looked at from the viewpoint of Marxist economics or the traditional balance of power, with little attempt to understand the role of ethnic factors” (33).

It seems that the concepts of identity and identity politics have beguiled, fascinated, troubled, frustrated, irked, and angered academics in the U.S. since at least the 1960s. Today is no exception. The study of group identity is flourishing in academia. A Google scholar search for the term “group identity” yields over 700,000 results. The term “identity politics” produces more than 600,000 results, nearly 33,000 of which have appeared since 2017. Despite overwhelming interest in the concept, however, it is not often that scholars take the opportunity we have been given—to step back from the minutiae of our research to consider not just the normative implications of group identities, but also to reflect on the social and political implications of studying the concept in the first place.

From where I’m sitting, as a social scientist, it appears that my discipline often overlooks such opportunities. We largely see our academic work as taking a positivist approach that reveals the world simply as it is and not as we would like it to be. But some might argue that in studying group identities, we are breathing too much life into a problematic concept. The most common critique of identity politics is that it is fracturing society, allowing groups to make political demands that narrowly benefit their group at the expense of the greater good.2 Some have argued, for instance, that the failings of the Democratic Party in the U.S. lie in its obsession with the rhetoric of diversity and the degree to which it has over-extended itself and alienated mostly white Americans by appealing explicitly to Black, Latino, and LGBT voters. Others have argued that identity politics is what drives support for far-right leaders, and it is the impetus for the rise of white nationalist and white supremacist groups. From these perspectives, there is little social utility to identity politics, and so far from being studied, it should be snuffed out.

Another, albeit less common, critique is that academics who study racial identity as part of a normative effort to achieve racial equality are misguided. It is not race, but rather class and economic inequality, on which our efforts should be focused. Undoubtedly, economic inequality is an enormous problem in a democratic society where citizens claim to value egalitarian norms. But this puzzling juxtaposition misses some fundamental points. The first is that racial identity is not merely a “celebration of difference,” nor is it a distraction from efforts to achieve economic inequality. Suggesting that attending to identity politics is what keeps us from fighting growing inequality is just barking up the wrong tree.

Both racial identity and economic inequality in the U.S. are the products of the construction and maintenance of the idea of race both as a somewhat inevitable feature of human psychology and as a politically, economically, and socially strategic project. This project dates back to European conquest, colonization, and slavery and is long rooted in the service of creating and maintaining the power and dominant status of people deemed white at the expense of other groups. When we understand race in this way, we can see that the question we should be asking today is not what politics we are enabling by studying racial identity, but instead what politics are we enabling by not studying racial identity.

One answer is that we are enabling the politics of colorblindness, which strategically dismisses the value of racial identities among subordinated groups to disempower them. What social science makes clear is that for black Americans and other marginalized groups, identity politics has been a tool to fight centuries of racial oppression. Identity politics is the foundation from which black Americans and other marginalized groups have fought for access to political, social, and economic power. It was the fuel for the Civil Rights Movement, which led to black Americans’ democratic inclusion. If we pejoratively dismiss, for instance, “black identity” as merely self- absorbed, neoliberal theater, we make several mistakes. The first is that we miss the extent to which identities are ways that groups have reclaimed and preserved dignity in the face of centuries of being told their art and music and literature and so on is inferior because of the arbitrary concept of race. Second, and more to the point, we miss that racial identities are what members of marginalized groups use collectively to fight against an arbitrary distinction that makes them more likely to be denied a job or a mortgage, to be incarcerated, to be killed by a police officer, to be denied adequate medical treatment, and so forth. Put bluntly, supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement are not protesting on the streets because they feel black history month does not adequately celebrate their group; they are protesting to demand that police officers no longer murder members of their group because of their race. And finally, by railing against identity politics among racial and ethnic minority groups, we undermine, dismiss, and insult the very tool marginalized groups have used strategically and effectively to fight for greater equality.

Among white Americans, by not studying identity, we also overlook an important reality: Racism comes not only from the irrational hostilities or prejudices harbored by some individuals, but also from a sense of solidarity many whites feel with their racial group.3 This sense of white identity exists in the service of maintaining the racial hierarchy—one that affords whites significant power, privileges, and resources. Racial identity for whites, then, is a tool for maintaining the status quo established via the long project of race-making. By ignoring this truth about the world, we enable the politics of strategic plausible deniability. We allow politicians and elites to claim that draconian immigration policies, colorblindness, ending affirmative action, denying reparations, and rejecting diversity are in the service of national unity. Instead, we should see them for what they typically are: efforts to maintain white dominance.

By studying the role of race and racial identities, we can be more clear-eyed about the extent to which elites use whites’ status in the racial hierarchy as a way to distinguish working class whites from working class blacks. Similarly, we can recognize that the enduring political strategy of stoking whites’ racial fears is meant to stymie the development of class solidarity. It also serves to motivate whites to vote against their own class interests in order to consolidate whites’ social and economic power. One path to fighting economic inequality therefore comes not from criticizing the left for promoting identity politics, or scholars for studying it, but instead from working to dismantle the racial hierarchy that facilitates the need for identity politics in the first place.

Notes

[tab: Michaels]

Walter Benn Michaels

At a crucial moment in The Leopard’s Spots (1902)—it’s when a young white woman has disappeared and she’s believed to have been raped and murdered by a “damned black beast”—Thomas Dixon describes the effect of fear and anger on the assembled crowd. “In a moment,” he says, “the white race had fused into a homogenous mass of love, sympathy, hate and revenge. The rich and the poor, the learned and the ignorant, the banker and the blacksmith, the great and the small, they were all one now.”

I know about this moment because, 25 years ago, I wrote what might plausibly (or at least partially) be described as a literary history of white identity (Our America: Nativism, Modernism, and Pluralism) and this passage seemed to me then as it seems to me now very useful for understanding what white identity did—it made people who were in many respects very different (rich and poor, learned and ignorant) feel that they were in a crucial sense the same. But, of course, that’s too anodyne a description. It would be better to say it made them mistakenly feel they were the same. As Judith Stein argued, in a world where the class interests of white planters and industrialists depended on “the exploitation of black labor” and thus on preventing blacks and poor whites from uniting to assert their class interests, both white identity and black identity were useful inventions.1 From the standpoint of capital, it was important for poor whites to see blacks not as fellow workers but as “beasts.” And, also from the standpoint of capital, it was at least as important for blacksmiths to see bankers not as their class enemy but as their racial brothers.

Today, of course, among liberals, it’s black identity more often than white that’s invoked as a technology of solidarity. Think of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s praise for Critical Race scholars at Harvard Law School articulating a “radical” “redistributional conception of law teaching jobs” which viewed those “positions as resources that should be shared with communities of color.”2 If you were to characterize the relation between poor black people and black Harvard professors in terms of class rather than community, it would be adversarial—the difference between people who get paid a great deal of money to make capitalism work and people who get paid almost no money also to make capitalism work. But once you replace class with color, the rewards of your job at Harvard can be imagined as shared with rather than extracted from at least some of the people who are cleaning your office and serving your meals. Apparently, we hope that even if Dixon’s dream hasn’t come true—if the white students at Bunker Hill Community College aren’t filled with pride by the sight of all the white students at Harvard—racial identity might still work for black people, turning rich people of color into the representatives rather than the adversaries of poor people of color.

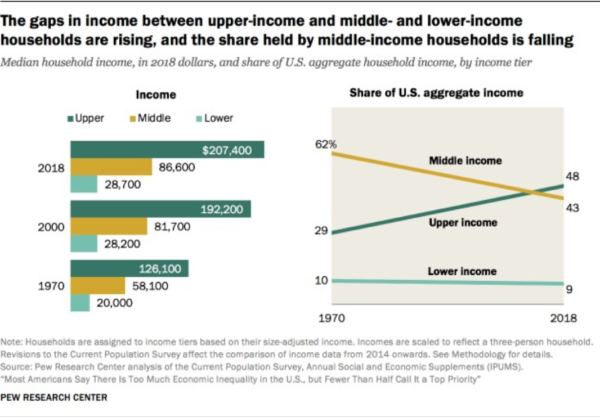

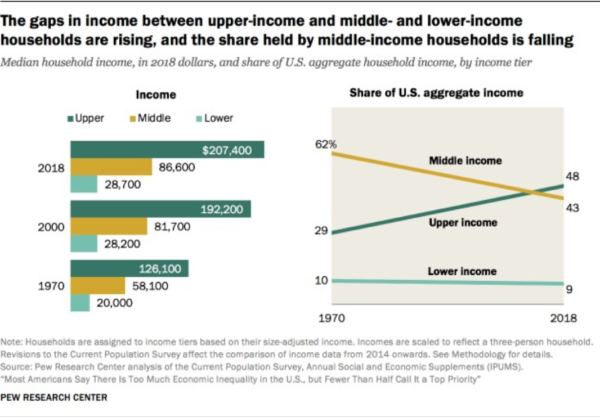

By contrast, the value of white identity today is as a site of abjection. What today’s blacksmith has in common with the banker is not the “soul of a race of pioneer white freemen” but a knapsack filled with privilege. Nonetheless, that knapsack performs the same function. In a society where, for the last half century, the difference between rich people and the poor (of all races) has steadily increased, it redescribes that difference as the disparity between white and black.3

Pride in white identity defended the class system by reassuring poor whites that what they had in common with rich whites—their whiteness—was more valuable than what separated them—their money. Guilt about white privilege defends the class system by reassuring rich whites (and rich people of color too) that if they can just redistribute not the wealth but the skin colors of the people who hold the wealth, everything will be OK—that the underrepresentation of black and brown people among the rich (rather than the mere existence of the rich) is the problem.

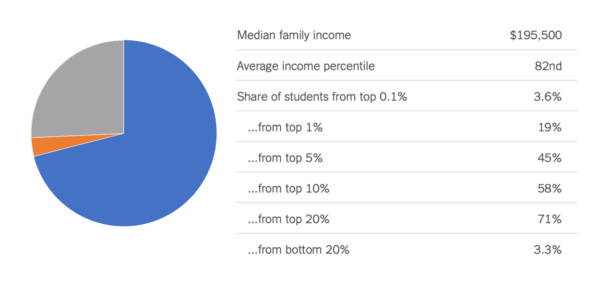

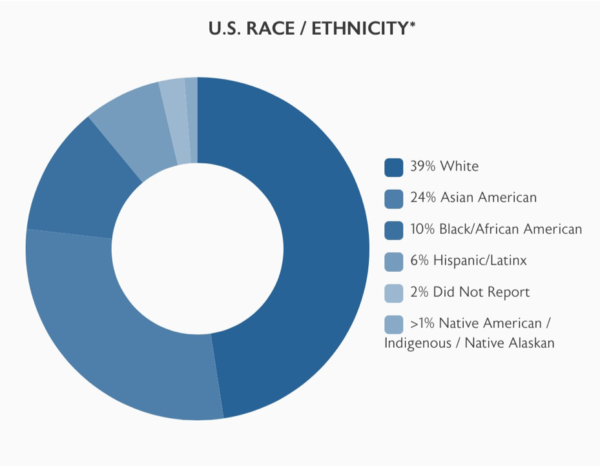

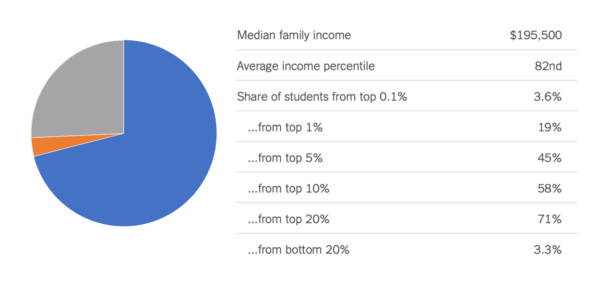

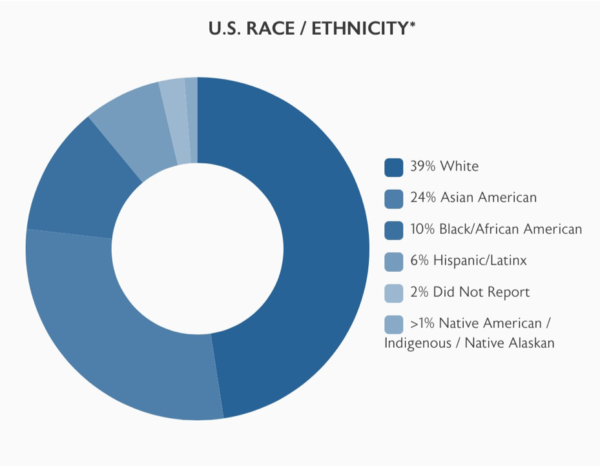

Nothing illustrates the appeal of this vision better than institutions like the ones we represent. At Penn, for example, the student body is about 41% white, 7.5% black, 10% percent Latinx and 20% Asian.4 The proportions aren’t perfect but they’re way better than the numbers for income. If I showed you the chart below and told you the 71% in blue was white people at Penn, we’d all be outraged. But when I tell you it’s rich people, no one’s even surprised: Penn so white is a scandal; Penn so rich is a business model.

So white identity does a lot of work, and—since naturalizing the inequalities produced by capitalism confronts rich people not with the prospect of their extinction but only with the need to add a few black and brown people to their mix—it does it mainly for rich white people. Every time a white student at Wharton checks his privilege, a venture capitalist gets her wings.5

But if you ask most white people to check their privilege, they’re hard put even to find it. The bottom 50% of white people hold less than three 3% of white wealth. And if it’s still true that (despite Wharton’s leadership) most of the rich people in the U.S. (81% of those making over $200K) are white (next come Asian Americans with 9%, what’s left is divided between black and brown people), it’s also true that most of the poor people are white, and it makes no more sense to translate the fact that white people are over-represented among the rich into white privilege than it would to translate the over-representation of Asian Americans into Asian privilege. Or rather, it makes exactly the same kind of non-sense. What good is the money of rich Asians to poor Asians? Actually, in the same post-1970 period in which inequality in the U.S. has been increasing, it’s increased most among Asian Americans who, if only in this respect, truly are the model minority—they’ve led the way in income inequality.6

Furthermore, it’s not just that the focus on white privilege hurts poor white people, it also hurts poor black people. Why? Because, in making the gap between whites and blacks the primary object of our attention we ignore a crucial contributor to keeping black people disproportionately poor: the fact that even though the various anti-discrimination measures put into place over the last half century have been effective in producing a 30% rise in relation to white earnings, the general (non-race specific) increase in inequality between blacks and whites has utterly negated that rise and left things almost exactly where they were in 1968.7 Of course, even the vanished 30% rise would not be enough, and no one (in this discussion anyway) thinks we should abandon a complete commitment to anti-discrimination. But anti-discrimination can’t make things better for poor black people as long as everything else is making things worse for poor people of every race.

And, even if it could and you could eliminate the gap between black and white without radically decreasing the gap between rich and poor you would not, of course, have a more equal society, you would just have a racially proportionate unequal one. Which, it seems to me, is the great utility of the concern with white privilege today: it replaces a goal that is utterly antithetical to capitalism (equality) with a goal that neoliberal capitalism has learned to embrace (racial equality). In doing so, it transforms the leftist ambition to eliminate the gap between the rich and the poor into the conservative ambition to make sure that racism doesn’t play any role in determining who gets to be rich and poor. Thus, coupled with the concept of systemic racism, the concept of white privilege succeeds in emptying the commitment to equality of any political edge and redeploying it on the fields of human resources and personal morality.

Systemic racism has its origin in the theory of institutional racism, which “challenged the idea that inequality” resulted from “prejudice alone,” and pointed to the ways in which “social institutions” could produce “different opportunities” for whites and blacks.8 But what began as the effort to explain racialized consequences even when some people weren’t actually racist has now become a way to describe a society in which almost everyone is imagined to be in some degree racist—“biased” if not exactly prejudiced, and insufficiently alert to the racialized consequences of their actions, words, etc. This is how antiracism becomes a moral and personal project; as Ibram Kendi says in How to Be an Antiracist, “The heartbeat of antiracism is confession… We must continuously reflect on ourselves so that we can reflect on our society.” Of course, some of us end up reflecting more on other people than ourselves but the point is the same: antiracism centers the individual’s effort to be good. And it’s no respecter of class; it enables us to distinguish between the virtuous and the unvirtuous poor; more useful still, it enables us to distinguish between the unvirtuous poor and the virtuous rich and, perhaps most useful of all, it enables us to distinguish between the virtuous and unvirtuous rich.

My point here is not that these distinctions are illusory but that they’re merely moral, that is, moral instead of political. Morally, we all prefer rich people who don’t lie and cheat and who give money to causes we approve and who actually follow through and recruit more people of color into higher management. Politically, why should we care how rich people behave? Our goal is to redistribute wealth and transfer power to workers, to get rid of rich people not to make them more effective HR managers.

Of course, I don’t mean to suggest that anti-racism in itself is conservative; I mean that anti-racism by itself is conservative. This conservativism is obvious when we worry about racism on corporate boards or about how many people of color get to teach at or attend elite universities. But it’s even there when we worry about the disproportionate number of unarmed black people shot by the police or about the disproportionate number of people of color in poverty. Conservativism is baked into the logic of disproportionality, into an anti-racism or anti-sexism that identifies the injustice of inequality with discrimination. And it’s that identification that’s promulgated by the interest in white identity and white privilege, which is why the only thing we should do with white identity is expose it for the con it is and why the effort to get rid of white privilege should be understood as simply an instance of the universalist effort to get rid of privilege itself.

Notes

[tab: Silver]

Hadass Silver

White identity and white privilege scholars argue that we must understand whiteness and the advantages it confers to address racial inequity and inequality. But the contrary is true. Whiteness and white privilege studies buttress a racially inegalitarian status quo. The claim that one’s whiteness provides meaningful information about one’s beliefs and experiences reifies racial categories used to exploit and dehumanize nonwhites. And the claim that whiteness confers “privilege” hamstrings efforts to realize meaningful racial equality by undermining cross-racial worker solidarity and calls for universal goods. Ultimately, scholarship that centers “understanding whiteness” and “white privilege” promotes conservative politics that harm most Black and brown Americans.

Marxist activists and critical race theorists Noel Ignatiev and Ted Allen are widely recognized as the forefathers of whiteness studies and white privilege discourse. Like Marx—who wrote that “labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin, when in the black it is branded”1 —Ignatiev and Allen believed that social, economic, and political equality could only be advanced by a unified, multiracial proletariat. However, unlike their predecessors, Ignatiev and Allen argued that overcoming white supremacy was a precondition of proletarian revolution. To dismantle white supremacy, they asserted, white workers needed to renounce their “white-skin privileges.” Ignatiev and Allen explained that such privileges—like “a monopoly of the skilled job” and “health and education facilities superior to those of the nonwhite population”—were developed by the bourgeoisie to inhibit the formation of a united working class opposed to bourgeois interests.2 While these fleeting privileges enticed white workers, Ignatiev and Allen argued that they were ultimately shackles. By deterring cross-racial worker solidarity, these “privileges” subverted white workers’ true material, social, and human interests.

Contemporary white privilege theorists agree with Ignatiev and Allen that white people must abandon their privileges to advance racial equality. However, unlike Ignatiev and Allen, these scholars argue that white privileges meaningfully improve the lives of all white people, and they abandon the fight for cross-racial, worker solidarity. In 1969, the Weathermen—drawing inspiration from third world and Black liberation movements—initiated this break with Marxist thought. Ever since, calls for racial solidarity and universalized goods have been increasingly supplanted by calls for identity politics and particularized demands. This shift has come at the expense of the most exploited members of society, including the majority of Black and brown Americans.

Examining what whiteness scholars mean by “white” and “white privilege” reveals the quotidian politics their work promotes. Although “white” is not used univocally in or across these works, when the term is used, it consistently reifies racial categories. Take the definitions of “white” offered by white privilege scholars Barbara Flagg and Charles W. Mills. Flagg defines a white person “as an individual of European descent who… has no known trace of African or other non-European ancestry.”3 Mills similarly equates European and white when he writes, “Both globally and within particular nations… white people, Europeans and their descendants, continue to benefit from the Racial Contract.”4 Here, both Flagg and Mills (astoundingly) use segregationists’ one-drop rule to taxonomize people by race. Although those who identify as white usually have European ancestry, “white” and “having European ancestry” are not synonymous. There have always been groups within Europe excluded from the categories—e.g., Aryan, Anglo-Saxon, etc.— analogous to the American category of “white.” By using “white people” as a proxy for “Europeans and their descendants,” Flagg and Mills—like many white privilege scholars—advance white supremacists’ position that race is objectively discernable.

When not appealing to geneticist or culturist understandings of race, white privilege scholars use circular logic. Whiteness, they claim, confers power and privilege because powerful and privileged people are white. Mills also offers this understanding of whiteness when he asserts, “Whiteness is not really a color at all, but a set of power relations.”5 White guilt evangelist Robin DiAngelo does so too when she states, “Race… was created to legitimize racial inequality and protect white advantage.”6 In these statements, Mills and DiAngelo, like most white privilege scholars, assume their conclusions from the outset: white people created whiteness to secure white privilege, they profess. In so doing, these scholars obscure the origins of “white” and “whiteness” and the mechanism through which these concepts are maintained. Rather than demystifying and undermining whiteness, they naturalize it.

The phrase “white privilege”—as used by its scholars—similarly undercuts efforts to confront racial disparity and inequality. In my work, I argue that “white privilege,” as it appears in the literature, takes one—or some combination—of five different meanings. “White privilege” may mean that: (1) white people have greater access to material resources than do nonwhites, (2) white people enjoy rights nonwhites cannot, (3) white culture and white perspectives are viewed as normal, (4) white people psychologically benefit from a sense of racial superiority, and (5) white people are not discriminated against for being white. Almost all of these definitions of white privilege distort reality and buttress racial inequality: only the last avoids these pitfalls. Yet this final definition does little more than assert that racial discrimination exists.

In discussing whiteness scholars’ definition of “white,” I have already articulated much of my argument against the third understanding of white privilege—that white culture and white perspectives are viewed as normal—and will not address it further for brevity’s sake. I will also not examine the fourth definition for the same reason. Here, I offer a brief discussion of the remaining three.

Whiteness scholars often use the first definition of “white privilege” above: that white people, on average, have greater access to material resources than do nonwhites. To support this claim, they note that Hispanics, African Americans, and Native Americans all experience higher rates of poverty than do white people. However, this fact does not justify using “white privilege” as a proxy for “economic privilege.” That nonwhites are disproportionately under-resourced does not make most white people well-resourced. In 2017, 10.1% of non-Hispanic white Americans lived in poverty.7 Given that 1/20th of the total U.S. population consists of white people living in poverty, it is not only absurd to equate whiteness with economic security—let alone economic privilege—it is unethical. By implying that economic hardship primarily derives from the differential treatment of whites and nonwhites, this equivalence distracts from the systemic mechanisms that underlie material disparities. Because, like many nonwhites, many whites receive a $7.25 minimum wage, experience asset poverty, are uninsured, and are unemployed, using “white privilege” to denote “economic privilege” obscures how such injustices contribute to economic hardship.

Instead, by using “white privilege” to denote “economic privilege,” white privilege scholars exclusively highlight the racial wealth gap. In so doing, they sidestep questions of economic justice and focus solely on the well-being of upper-class nonwhites, ignoring poor and working-class people of color.

The call to close the racial wealth gap does not adjudicate between lifting all races to the “white standard” (meaning that 10.1% of nonwhites would still be under the poverty line) or lowering all races to the “Native American standard” (meaning that 25.4% of all Americans, regardless of race or ethnicity, would be living under the poverty line).8 Of course, a white privilege scholar might counter that she and her peers obviously advocate for increasing the economic security of nonwhites, not decreasing that of whites. But, for anyone concerned with the material well-being of all nonwhites (or all humans, for that matter), this is not assuring. Why strive for having 1/10th of nonwhite Americans living in poverty? Why not aim higher? Ultimately, white privilege discourse is unconcerned with nonwhites whose economic hardships would go unaddressed by closing the racial wealth gap. When disaggregated, “the racial wealth gap is almost entirely about the upper classes in each racial group.” “The overall racial wealth disparity is being driven almost entirely by the disparity between the wealthiest 10 percent of white people and the wealthiest 10 percent of black people,” and “97 percent of the overall racial wealth gap is driven by households above the median of each racial group.”9 By focusing on the racial wealth gap, white privilege scholars promote the betterment of wealthier nonwhites, leaving economic justice unexamined and the situation of poorer nonwhites unchanged.

White privilege scholars also use disparities in the criminal justice system to assert that white people enjoy rights nonwhites cannot. My critique of the first definition applies to the second as well. Undoubtedly, overt racism and racial bias contribute to the overrepresentation of nonwhites at every stage of the criminalization process. But, asserting that “white privilege” drives this disparity fails to identify its underlying causes. Mass incarceration was created and is maintained to: enrich profit-driven actors (like the owners of private prisons and the phone companies that service them); house the mentally ill and homeless; criminalize the activities of unemployed, labor reserves to fuel worker competition, and so on. While nonwhites are disproportionately the victims of this system and dehumanizing them helps perpetuate it, privileging the white majority is not mass incarceration’s raison d’être. In suggesting that white privilege produces racial inequity in the criminal justice system—and that white people renouncing said privilege can rectify this—white privilege scholars fail to offer pragmatic solutions to inequities and injustices in the American justice system. Moreover, it is entirely unclear how white people can, or why they should, renounce the “privilege” of having their rights protected, were they to have this privilege in the first place. But, nonwhites are not the only people disproportionately warehoused in prisons. So too are low-income and mentally ill white people.

The fifth definition of white privilege states that those socially identified as white are not discriminated against for being white. This is absolutely true. Yet, this truth can be—and, until recently, was—expressed more productively. Characterizing humane treatment as a “privilege” is not a marker of a progressive, antiracist agenda. Abolitionists did not call freedom a “privilege,” they called slavery an injustice. Civil rights leaders did not call voting a “privilege,” they called voter suppression an injustice. And we should not call avoiding racial prejudice a “privilege,” we should call discrimination an injustice.

However, white privilege scholars rarely use this fifth definition of white privilege. This is because they want to do more than rename “racial discrimination” “white privilege”: they want to describe how racial discrimination privileges white people and how white privilege perpetuates racial discrimination. Yet, even this final, bare-bones definition of “white privilege” fails to promote racial equity or equality. Instead, it, like the other forms of “white privilege,” helps sustain the inegalitarian status quo.

All told, the study of white identity and white privilege encourages moralization and rumination, not understanding and action. It is a politics that tells white elites to make more room for nonwhite elites, poor and working-class white people that they are privileged, and, once again, ignores poor and working-class Black and brown people.

Notes

You can watch the full event here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wqTfM56s4aA.

Introduction

Katherine Rader

The essays included in this symposium were written by the panelists for the event “Checking Your Privilege? Perspectives on the Politics of White Identity,” hosted by the Andrea Mitchell Center at the University of Pennsylvania in March 2021.1 In preparation for the panel, each panelist prepared a short essay addressing the question, “What kind of politics are enabled by the study of white identity and/or white privilege?” This notion has garnered significant attention from politicians, activists, and academics alike in the past half-century. Proponents argue that “checking” this privilege or reforming white identity (think: Peggy McIntosh and the Invisible Knapsack) is a necessary first step in dismantling structural racism. Critics of this position argue that this insistence on a shared white identity actually obscures the material basis of contemporary racism and hampers efforts to achieve meaningful racial equality. Ultimately, these arguments connect back to debates over identity politics and the utility of a politics or political analysis grounded in group demarcation.

The hope was that in focusing on the politics enabled by the study of white identity and white privilege, the panel might avoid the trap of the esoteric academic panel and engage a broader audience around the political question (at least in numbers we were somewhat successful here, with over 900 registrants to the event). The panelists invited to participate in this event represented these two broad perspectives on white identity and approached these questions from a variety of methodological, epistemological, and disciplinary perspectives. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva is a professor in sociology and African American Studies at Duke University and author of Racism without Racists: Color-blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America, which explores the ideology of “color-blind racism.” Ashley Jardina is an assistant professor of political science at Duke University and author of the 2019 book White Identity Politics, which offers empirical evidence of a discernible and politically significant white racial group identification. Hadass Silver is a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania and is currently writing a critical theory dissertation examining white privilege discourse and its connections to movements for racial and economic justice. Walter Benn Michaels is a professor in English at the University of Illinois at Chicago and author of The Trouble with Diversity, where he considers how the pervasive focus on diversity obscures issues of economic inequality.

The goal of the panel, as Jardina aptly put it, was to “step back from the minutiae of our research to consider not just the normative implications of group identities, but also to reflect on the social and political implications of studying the concept in the first place.” Unsurprisingly, one central political goal shared by all the panelists is to secure greater racial equality. In addition, three of the four papers (save Jardina’s) point to the necessity of a more economically redistributive version of democratic socialism for the realization of greater racial equality. But these shared goals did not occupy the majority of the discussion, rather it hinged on the question of whether the study of white identity could further or hinder racial equity and democratic socialism.

The first position, advanced by Bonilla-Silva and Jardina, is that issues of white identity and other racial divisions need to be addressed before other political projects can be pursued. Bonilla-Silva, invoking Charles Mills and Stuart Hall, argues that to attain a democratic socialist society, it is first necessary to confront and deconstruct racial divisions. In other words, the primary obstacles to realizing democratic socialism are racial divisions and animus.2 However, Bonilla-Silva does not lay the blame at the feet of fringe white nationalists—he argues that “nice white liberals” and those with even “marginal whiteness” materially benefit from the production of a white habitus and systemic racism. Further, Jardina contends that “racial identities are what members of marginalized groups use collectively to fight against an arbitrary distinction.” In other words, these identities have become necessary tools for fighting for racial equity. And crucially, both scholars maintain that subsuming issues of race into a broader pursuit of redistribution or equality would have a deleterious effect on struggles for racial justice.

Silver and Michaels, on the other hand, push back against the idea that racial reckoning in the mold of white identity and privilege discourse is a necessary first step. Rather, they argue that such a focus is, in fact, a detractor from a broader social-democratic agenda. Instead of working to advance shared goals, Silver argues that “implying that economic hardship primarily derives from the differential treatment of whites and nonwhites” ultimately “distracts from the systemic mechanisms that underlie material disparities.” Michaels attends closely to these material disparities—pointing out that these “material benefits” incurred by whiteness are not clear when considering the trajectory of economic inequality in the past half-century, when “the difference between rich people and the poor (of all races) has steadily increased, [the knapsack] redescribes that difference as the disparity between white and black.”

The panel discussion itself expanded on these key themes and questions from the audience attempted to probe further into the consequences of these identity politics debates for contemporary struggles on the left, including the Black Lives Matter movement and the Amazon unionization campaign in Bessemer, Alabama. While the discussion hardly resolved these sharp differences, it certainly shed light on this increasingly prominent debate over identity politics and the potential for racial and economic equality.

Notes

[tab: Jardina]

Ashley Jardina

In the 1970s, four scholars participated in a panel discussion for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. They were asked to address questions about the social and academic value of ethnic identity.1 In response, Orlando Patterson, a professor of sociology, wrote, “The particularistic and divisive social philosophy of pluralism is, in my mind, one of the most tragic intellectual developments of our time” (32). Taking a somewhat more sanguine perspective, University of Chicago sociologist Andrew Greeley lamented the lack of diversity within the academy and wrote, “The critical challenge is not to eliminate or reject ethnic identity—that is a self-defeating effort—but rather to understand how diversity and the tensions it engenders can be integrated into some form of unity” (25). In response, the Harvard sociologist and soon-to-be U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan told both Patterson and Greely, somewhat snidely, to get over themselves. They should instead, he argued, accept the world as it is, which for Moynihan meant acknowledging that, “For too long, world affairs have been looked at from the viewpoint of Marxist economics or the traditional balance of power, with little attempt to understand the role of ethnic factors” (33).

It seems that the concepts of identity and identity politics have beguiled, fascinated, troubled, frustrated, irked, and angered academics in the U.S. since at least the 1960s. Today is no exception. The study of group identity is flourishing in academia. A Google scholar search for the term “group identity” yields over 700,000 results. The term “identity politics” produces more than 600,000 results, nearly 33,000 of which have appeared since 2017. Despite overwhelming interest in the concept, however, it is not often that scholars take the opportunity we have been given—to step back from the minutiae of our research to consider not just the normative implications of group identities, but also to reflect on the social and political implications of studying the concept in the first place.

From where I’m sitting, as a social scientist, it appears that my discipline often overlooks such opportunities. We largely see our academic work as taking a positivist approach that reveals the world simply as it is and not as we would like it to be. But some might argue that in studying group identities, we are breathing too much life into a problematic concept. The most common critique of identity politics is that it is fracturing society, allowing groups to make political demands that narrowly benefit their group at the expense of the greater good.2 Some have argued, for instance, that the failings of the Democratic Party in the U.S. lie in its obsession with the rhetoric of diversity and the degree to which it has over-extended itself and alienated mostly white Americans by appealing explicitly to Black, Latino, and LGBT voters. Others have argued that identity politics is what drives support for far-right leaders, and it is the impetus for the rise of white nationalist and white supremacist groups. From these perspectives, there is little social utility to identity politics, and so far from being studied, it should be snuffed out.

Another, albeit less common, critique is that academics who study racial identity as part of a normative effort to achieve racial equality are misguided. It is not race, but rather class and economic inequality, on which our efforts should be focused. Undoubtedly, economic inequality is an enormous problem in a democratic society where citizens claim to value egalitarian norms. But this puzzling juxtaposition misses some fundamental points. The first is that racial identity is not merely a “celebration of difference,” nor is it a distraction from efforts to achieve economic inequality. Suggesting that attending to identity politics is what keeps us from fighting growing inequality is just barking up the wrong tree.

Both racial identity and economic inequality in the U.S. are the products of the construction and maintenance of the idea of race both as a somewhat inevitable feature of human psychology and as a politically, economically, and socially strategic project. This project dates back to European conquest, colonization, and slavery and is long rooted in the service of creating and maintaining the power and dominant status of people deemed white at the expense of other groups. When we understand race in this way, we can see that the question we should be asking today is not what politics we are enabling by studying racial identity, but instead what politics are we enabling by not studying racial identity.

One answer is that we are enabling the politics of colorblindness, which strategically dismisses the value of racial identities among subordinated groups to disempower them. What social science makes clear is that for black Americans and other marginalized groups, identity politics has been a tool to fight centuries of racial oppression. Identity politics is the foundation from which black Americans and other marginalized groups have fought for access to political, social, and economic power. It was the fuel for the Civil Rights Movement, which led to black Americans’ democratic inclusion. If we pejoratively dismiss, for instance, “black identity” as merely self- absorbed, neoliberal theater, we make several mistakes. The first is that we miss the extent to which identities are ways that groups have reclaimed and preserved dignity in the face of centuries of being told their art and music and literature and so on is inferior because of the arbitrary concept of race. Second, and more to the point, we miss that racial identities are what members of marginalized groups use collectively to fight against an arbitrary distinction that makes them more likely to be denied a job or a mortgage, to be incarcerated, to be killed by a police officer, to be denied adequate medical treatment, and so forth. Put bluntly, supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement are not protesting on the streets because they feel black history month does not adequately celebrate their group; they are protesting to demand that police officers no longer murder members of their group because of their race. And finally, by railing against identity politics among racial and ethnic minority groups, we undermine, dismiss, and insult the very tool marginalized groups have used strategically and effectively to fight for greater equality.

Among white Americans, by not studying identity, we also overlook an important reality: Racism comes not only from the irrational hostilities or prejudices harbored by some individuals, but also from a sense of solidarity many whites feel with their racial group.3 This sense of white identity exists in the service of maintaining the racial hierarchy—one that affords whites significant power, privileges, and resources. Racial identity for whites, then, is a tool for maintaining the status quo established via the long project of race-making. By ignoring this truth about the world, we enable the politics of strategic plausible deniability. We allow politicians and elites to claim that draconian immigration policies, colorblindness, ending affirmative action, denying reparations, and rejecting diversity are in the service of national unity. Instead, we should see them for what they typically are: efforts to maintain white dominance.

By studying the role of race and racial identities, we can be more clear-eyed about the extent to which elites use whites’ status in the racial hierarchy as a way to distinguish working class whites from working class blacks. Similarly, we can recognize that the enduring political strategy of stoking whites’ racial fears is meant to stymie the development of class solidarity. It also serves to motivate whites to vote against their own class interests in order to consolidate whites’ social and economic power. One path to fighting economic inequality therefore comes not from criticizing the left for promoting identity politics, or scholars for studying it, but instead from working to dismantle the racial hierarchy that facilitates the need for identity politics in the first place.

Notes

[tab: Michaels]

Walter Benn Michaels

At a crucial moment in The Leopard’s Spots (1902)—it’s when a young white woman has disappeared and she’s believed to have been raped and murdered by a “damned black beast”—Thomas Dixon describes the effect of fear and anger on the assembled crowd. “In a moment,” he says, “the white race had fused into a homogenous mass of love, sympathy, hate and revenge. The rich and the poor, the learned and the ignorant, the banker and the blacksmith, the great and the small, they were all one now.”

I know about this moment because, 25 years ago, I wrote what might plausibly (or at least partially) be described as a literary history of white identity (Our America: Nativism, Modernism, and Pluralism) and this passage seemed to me then as it seems to me now very useful for understanding what white identity did—it made people who were in many respects very different (rich and poor, learned and ignorant) feel that they were in a crucial sense the same. But, of course, that’s too anodyne a description. It would be better to say it made them mistakenly feel they were the same. As Judith Stein argued, in a world where the class interests of white planters and industrialists depended on “the exploitation of black labor” and thus on preventing blacks and poor whites from uniting to assert their class interests, both white identity and black identity were useful inventions.1 From the standpoint of capital, it was important for poor whites to see blacks not as fellow workers but as “beasts.” And, also from the standpoint of capital, it was at least as important for blacksmiths to see bankers not as their class enemy but as their racial brothers.

Today, of course, among liberals, it’s black identity more often than white that’s invoked as a technology of solidarity. Think of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s praise for Critical Race scholars at Harvard Law School articulating a “radical” “redistributional conception of law teaching jobs” which viewed those “positions as resources that should be shared with communities of color.”2 If you were to characterize the relation between poor black people and black Harvard professors in terms of class rather than community, it would be adversarial—the difference between people who get paid a great deal of money to make capitalism work and people who get paid almost no money also to make capitalism work. But once you replace class with color, the rewards of your job at Harvard can be imagined as shared with rather than extracted from at least some of the people who are cleaning your office and serving your meals. Apparently, we hope that even if Dixon’s dream hasn’t come true—if the white students at Bunker Hill Community College aren’t filled with pride by the sight of all the white students at Harvard—racial identity might still work for black people, turning rich people of color into the representatives rather than the adversaries of poor people of color.

By contrast, the value of white identity today is as a site of abjection. What today’s blacksmith has in common with the banker is not the “soul of a race of pioneer white freemen” but a knapsack filled with privilege. Nonetheless, that knapsack performs the same function. In a society where, for the last half century, the difference between rich people and the poor (of all races) has steadily increased, it redescribes that difference as the disparity between white and black.3

Pride in white identity defended the class system by reassuring poor whites that what they had in common with rich whites—their whiteness—was more valuable than what separated them—their money. Guilt about white privilege defends the class system by reassuring rich whites (and rich people of color too) that if they can just redistribute not the wealth but the skin colors of the people who hold the wealth, everything will be OK—that the underrepresentation of black and brown people among the rich (rather than the mere existence of the rich) is the problem.

Nothing illustrates the appeal of this vision better than institutions like the ones we represent. At Penn, for example, the student body is about 41% white, 7.5% black, 10% percent Latinx and 20% Asian.4 The proportions aren’t perfect but they’re way better than the numbers for income. If I showed you the chart below and told you the 71% in blue was white people at Penn, we’d all be outraged. But when I tell you it’s rich people, no one’s even surprised: Penn so white is a scandal; Penn so rich is a business model.

So white identity does a lot of work, and—since naturalizing the inequalities produced by capitalism confronts rich people not with the prospect of their extinction but only with the need to add a few black and brown people to their mix—it does it mainly for rich white people. Every time a white student at Wharton checks his privilege, a venture capitalist gets her wings.5

But if you ask most white people to check their privilege, they’re hard put even to find it. The bottom 50% of white people hold less than three 3% of white wealth. And if it’s still true that (despite Wharton’s leadership) most of the rich people in the U.S. (81% of those making over $200K) are white (next come Asian Americans with 9%, what’s left is divided between black and brown people), it’s also true that most of the poor people are white, and it makes no more sense to translate the fact that white people are over-represented among the rich into white privilege than it would to translate the over-representation of Asian Americans into Asian privilege. Or rather, it makes exactly the same kind of non-sense. What good is the money of rich Asians to poor Asians? Actually, in the same post-1970 period in which inequality in the U.S. has been increasing, it’s increased most among Asian Americans who, if only in this respect, truly are the model minority—they’ve led the way in income inequality.6

Furthermore, it’s not just that the focus on white privilege hurts poor white people, it also hurts poor black people. Why? Because, in making the gap between whites and blacks the primary object of our attention we ignore a crucial contributor to keeping black people disproportionately poor: the fact that even though the various anti-discrimination measures put into place over the last half century have been effective in producing a 30% rise in relation to white earnings, the general (non-race specific) increase in inequality between blacks and whites has utterly negated that rise and left things almost exactly where they were in 1968.7 Of course, even the vanished 30% rise would not be enough, and no one (in this discussion anyway) thinks we should abandon a complete commitment to anti-discrimination. But anti-discrimination can’t make things better for poor black people as long as everything else is making things worse for poor people of every race.

And, even if it could and you could eliminate the gap between black and white without radically decreasing the gap between rich and poor you would not, of course, have a more equal society, you would just have a racially proportionate unequal one. Which, it seems to me, is the great utility of the concern with white privilege today: it replaces a goal that is utterly antithetical to capitalism (equality) with a goal that neoliberal capitalism has learned to embrace (racial equality). In doing so, it transforms the leftist ambition to eliminate the gap between the rich and the poor into the conservative ambition to make sure that racism doesn’t play any role in determining who gets to be rich and poor. Thus, coupled with the concept of systemic racism, the concept of white privilege succeeds in emptying the commitment to equality of any political edge and redeploying it on the fields of human resources and personal morality.

Systemic racism has its origin in the theory of institutional racism, which “challenged the idea that inequality” resulted from “prejudice alone,” and pointed to the ways in which “social institutions” could produce “different opportunities” for whites and blacks.8 But what began as the effort to explain racialized consequences even when some people weren’t actually racist has now become a way to describe a society in which almost everyone is imagined to be in some degree racist—“biased” if not exactly prejudiced, and insufficiently alert to the racialized consequences of their actions, words, etc. This is how antiracism becomes a moral and personal project; as Ibram Kendi says in How to Be an Antiracist, “The heartbeat of antiracism is confession… We must continuously reflect on ourselves so that we can reflect on our society.” Of course, some of us end up reflecting more on other people than ourselves but the point is the same: antiracism centers the individual’s effort to be good. And it’s no respecter of class; it enables us to distinguish between the virtuous and the unvirtuous poor; more useful still, it enables us to distinguish between the unvirtuous poor and the virtuous rich and, perhaps most useful of all, it enables us to distinguish between the virtuous and unvirtuous rich.

My point here is not that these distinctions are illusory but that they’re merely moral, that is, moral instead of political. Morally, we all prefer rich people who don’t lie and cheat and who give money to causes we approve and who actually follow through and recruit more people of color into higher management. Politically, why should we care how rich people behave? Our goal is to redistribute wealth and transfer power to workers, to get rid of rich people not to make them more effective HR managers.

Of course, I don’t mean to suggest that anti-racism in itself is conservative; I mean that anti-racism by itself is conservative. This conservativism is obvious when we worry about racism on corporate boards or about how many people of color get to teach at or attend elite universities. But it’s even there when we worry about the disproportionate number of unarmed black people shot by the police or about the disproportionate number of people of color in poverty. Conservativism is baked into the logic of disproportionality, into an anti-racism or anti-sexism that identifies the injustice of inequality with discrimination. And it’s that identification that’s promulgated by the interest in white identity and white privilege, which is why the only thing we should do with white identity is expose it for the con it is and why the effort to get rid of white privilege should be understood as simply an instance of the universalist effort to get rid of privilege itself.

Notes

[tab: Silver]

Hadass Silver

White identity and white privilege scholars argue that we must understand whiteness and the advantages it confers to address racial inequity and inequality. But the contrary is true. Whiteness and white privilege studies buttress a racially inegalitarian status quo. The claim that one’s whiteness provides meaningful information about one’s beliefs and experiences reifies racial categories used to exploit and dehumanize nonwhites. And the claim that whiteness confers “privilege” hamstrings efforts to realize meaningful racial equality by undermining cross-racial worker solidarity and calls for universal goods. Ultimately, scholarship that centers “understanding whiteness” and “white privilege” promotes conservative politics that harm most Black and brown Americans.

Marxist activists and critical race theorists Noel Ignatiev and Ted Allen are widely recognized as the forefathers of whiteness studies and white privilege discourse. Like Marx—who wrote that “labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin, when in the black it is branded”1 —Ignatiev and Allen believed that social, economic, and political equality could only be advanced by a unified, multiracial proletariat. However, unlike their predecessors, Ignatiev and Allen argued that overcoming white supremacy was a precondition of proletarian revolution. To dismantle white supremacy, they asserted, white workers needed to renounce their “white-skin privileges.” Ignatiev and Allen explained that such privileges—like “a monopoly of the skilled job” and “health and education facilities superior to those of the nonwhite population”—were developed by the bourgeoisie to inhibit the formation of a united working class opposed to bourgeois interests.2 While these fleeting privileges enticed white workers, Ignatiev and Allen argued that they were ultimately shackles. By deterring cross-racial worker solidarity, these “privileges” subverted white workers’ true material, social, and human interests.

Contemporary white privilege theorists agree with Ignatiev and Allen that white people must abandon their privileges to advance racial equality. However, unlike Ignatiev and Allen, these scholars argue that white privileges meaningfully improve the lives of all white people, and they abandon the fight for cross-racial, worker solidarity. In 1969, the Weathermen—drawing inspiration from third world and Black liberation movements—initiated this break with Marxist thought. Ever since, calls for racial solidarity and universalized goods have been increasingly supplanted by calls for identity politics and particularized demands. This shift has come at the expense of the most exploited members of society, including the majority of Black and brown Americans.

Examining what whiteness scholars mean by “white” and “white privilege” reveals the quotidian politics their work promotes. Although “white” is not used univocally in or across these works, when the term is used, it consistently reifies racial categories. Take the definitions of “white” offered by white privilege scholars Barbara Flagg and Charles W. Mills. Flagg defines a white person “as an individual of European descent who… has no known trace of African or other non-European ancestry.”3 Mills similarly equates European and white when he writes, “Both globally and within particular nations… white people, Europeans and their descendants, continue to benefit from the Racial Contract.”4 Here, both Flagg and Mills (astoundingly) use segregationists’ one-drop rule to taxonomize people by race. Although those who identify as white usually have European ancestry, “white” and “having European ancestry” are not synonymous. There have always been groups within Europe excluded from the categories—e.g., Aryan, Anglo-Saxon, etc.— analogous to the American category of “white.” By using “white people” as a proxy for “Europeans and their descendants,” Flagg and Mills—like many white privilege scholars—advance white supremacists’ position that race is objectively discernable.

When not appealing to geneticist or culturist understandings of race, white privilege scholars use circular logic. Whiteness, they claim, confers power and privilege because powerful and privileged people are white. Mills also offers this understanding of whiteness when he asserts, “Whiteness is not really a color at all, but a set of power relations.”5 White guilt evangelist Robin DiAngelo does so too when she states, “Race… was created to legitimize racial inequality and protect white advantage.”6 In these statements, Mills and DiAngelo, like most white privilege scholars, assume their conclusions from the outset: white people created whiteness to secure white privilege, they profess. In so doing, these scholars obscure the origins of “white” and “whiteness” and the mechanism through which these concepts are maintained. Rather than demystifying and undermining whiteness, they naturalize it.

The phrase “white privilege”—as used by its scholars—similarly undercuts efforts to confront racial disparity and inequality. In my work, I argue that “white privilege,” as it appears in the literature, takes one—or some combination—of five different meanings. “White privilege” may mean that: (1) white people have greater access to material resources than do nonwhites, (2) white people enjoy rights nonwhites cannot, (3) white culture and white perspectives are viewed as normal, (4) white people psychologically benefit from a sense of racial superiority, and (5) white people are not discriminated against for being white. Almost all of these definitions of white privilege distort reality and buttress racial inequality: only the last avoids these pitfalls. Yet this final definition does little more than assert that racial discrimination exists.

In discussing whiteness scholars’ definition of “white,” I have already articulated much of my argument against the third understanding of white privilege—that white culture and white perspectives are viewed as normal—and will not address it further for brevity’s sake. I will also not examine the fourth definition for the same reason. Here, I offer a brief discussion of the remaining three.

Whiteness scholars often use the first definition of “white privilege” above: that white people, on average, have greater access to material resources than do nonwhites. To support this claim, they note that Hispanics, African Americans, and Native Americans all experience higher rates of poverty than do white people. However, this fact does not justify using “white privilege” as a proxy for “economic privilege.” That nonwhites are disproportionately under-resourced does not make most white people well-resourced. In 2017, 10.1% of non-Hispanic white Americans lived in poverty.7 Given that 1/20th of the total U.S. population consists of white people living in poverty, it is not only absurd to equate whiteness with economic security—let alone economic privilege—it is unethical. By implying that economic hardship primarily derives from the differential treatment of whites and nonwhites, this equivalence distracts from the systemic mechanisms that underlie material disparities. Because, like many nonwhites, many whites receive a $7.25 minimum wage, experience asset poverty, are uninsured, and are unemployed, using “white privilege” to denote “economic privilege” obscures how such injustices contribute to economic hardship.

Instead, by using “white privilege” to denote “economic privilege,” white privilege scholars exclusively highlight the racial wealth gap. In so doing, they sidestep questions of economic justice and focus solely on the well-being of upper-class nonwhites, ignoring poor and working-class people of color.

The call to close the racial wealth gap does not adjudicate between lifting all races to the “white standard” (meaning that 10.1% of nonwhites would still be under the poverty line) or lowering all races to the “Native American standard” (meaning that 25.4% of all Americans, regardless of race or ethnicity, would be living under the poverty line).8 Of course, a white privilege scholar might counter that she and her peers obviously advocate for increasing the economic security of nonwhites, not decreasing that of whites. But, for anyone concerned with the material well-being of all nonwhites (or all humans, for that matter), this is not assuring. Why strive for having 1/10th of nonwhite Americans living in poverty? Why not aim higher? Ultimately, white privilege discourse is unconcerned with nonwhites whose economic hardships would go unaddressed by closing the racial wealth gap. When disaggregated, “the racial wealth gap is almost entirely about the upper classes in each racial group.” “The overall racial wealth disparity is being driven almost entirely by the disparity between the wealthiest 10 percent of white people and the wealthiest 10 percent of black people,” and “97 percent of the overall racial wealth gap is driven by households above the median of each racial group.”9 By focusing on the racial wealth gap, white privilege scholars promote the betterment of wealthier nonwhites, leaving economic justice unexamined and the situation of poorer nonwhites unchanged.

White privilege scholars also use disparities in the criminal justice system to assert that white people enjoy rights nonwhites cannot. My critique of the first definition applies to the second as well. Undoubtedly, overt racism and racial bias contribute to the overrepresentation of nonwhites at every stage of the criminalization process. But, asserting that “white privilege” drives this disparity fails to identify its underlying causes. Mass incarceration was created and is maintained to: enrich profit-driven actors (like the owners of private prisons and the phone companies that service them); house the mentally ill and homeless; criminalize the activities of unemployed, labor reserves to fuel worker competition, and so on. While nonwhites are disproportionately the victims of this system and dehumanizing them helps perpetuate it, privileging the white majority is not mass incarceration’s raison d’être. In suggesting that white privilege produces racial inequity in the criminal justice system—and that white people renouncing said privilege can rectify this—white privilege scholars fail to offer pragmatic solutions to inequities and injustices in the American justice system. Moreover, it is entirely unclear how white people can, or why they should, renounce the “privilege” of having their rights protected, were they to have this privilege in the first place. But, nonwhites are not the only people disproportionately warehoused in prisons. So too are low-income and mentally ill white people.

The fifth definition of white privilege states that those socially identified as white are not discriminated against for being white. This is absolutely true. Yet, this truth can be—and, until recently, was—expressed more productively. Characterizing humane treatment as a “privilege” is not a marker of a progressive, antiracist agenda. Abolitionists did not call freedom a “privilege,” they called slavery an injustice. Civil rights leaders did not call voting a “privilege,” they called voter suppression an injustice. And we should not call avoiding racial prejudice a “privilege,” we should call discrimination an injustice.

However, white privilege scholars rarely use this fifth definition of white privilege. This is because they want to do more than rename “racial discrimination” “white privilege”: they want to describe how racial discrimination privileges white people and how white privilege perpetuates racial discrimination. Yet, even this final, bare-bones definition of “white privilege” fails to promote racial equity or equality. Instead, it, like the other forms of “white privilege,” helps sustain the inegalitarian status quo.

All told, the study of white identity and white privilege encourages moralization and rumination, not understanding and action. It is a politics that tells white elites to make more room for nonwhite elites, poor and working-class white people that they are privileged, and, once again, ignores poor and working-class Black and brown people.

Notes