Curated by Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale (May 28-November 27, 2016) focused on architectures that addressed large-scale problems using vernacular techniques.1 If the implicit theme of the 2013 Venice Art Biennale had been “outsider art,” characterized by Daily Telegraph critic Alistair Sooke as both “visionary” and “homespun,” the similarly unstated theme of this 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale can be understood as outsider architecture.2

Aravena’s Architecture Biennale foregrounded the outsider in two senses. Rather than a capital-intensive architecture of improbable forms and futuristic substances, set in cosmopolitan cities of the developed West, Aravena’s exhibition emphasized natural materials and labor-intensive techniques common to the Global South. What went unspoken, however, was the relationship between architecture’s insiders and its outsiders, between capital and labor, between the developed world and its other.

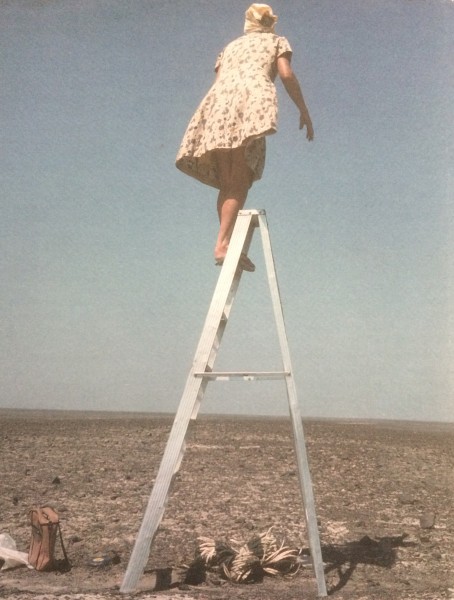

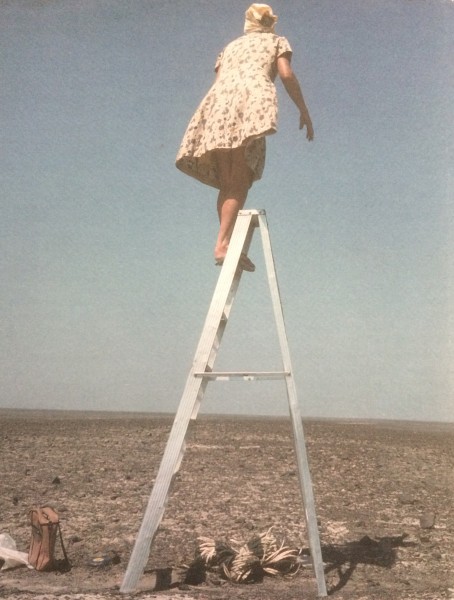

The image that Aravena chose for the exhibition collateral exemplified this problematic. On posters, banner ads, and catalogue covers, one found an image of an older woman on a ladder, set against a bright blue sky in an arid, unmarked landscape. In explaining the image, Aravena adopted a fable-like tone:

In his trip to South America [British travel writer] Bruce Chatwin encountered an old lady walking the desert carrying an aluminum ladder on her shoulder. It was German archeologist Maria Reiche studying the Nazca lines. Standing on the ground, the stones did not make any sense; they were just random gravel. But from the height of the stair those stones became a bird, a jaguar, a tree or a flower.3

Within the seemingly empty landscape of the Global South, a German scientist with her industrial tool (an aluminum ladder) analyzes the landscape; she “makes sense” of its secrets and potentialities. The image is an apt allegory for the current state of architectural interest in traditional or vernacular modes: non-expert architectural knowledge is extracted, repackaged and cloaked in the language of technology and sustainability, then re-learned back at its source. The problem of Aravena’s exhibition is not, though, reducible to a rather simplistic accusation of cultural appropriation. Instead, the crux of this Venice Architecture Biennale lies in its emphasis on so-called “social architecture,” even as it fails to question the socio-economic situations within which architects operate. In its implicit relationship of native, local, or vernacular resources to foreign, technological expertise, the fable of Maria Reiche undergirds the whole of Aravena’s exhibition. However, Aravena updates the fable, with the exhibition’s social architetures and vernacular forms culminating in a contemporary twist: a new neoimperial project for a network of drones across Africa.

Materials

Aravena should be commended for refusing a nostalgic or folkloric frame for traditional, “low-tech” construction techniques and materials. At no point were national mythologies or romantic visions of premodern communities invoked to validate the use of rammed earth, terra-cotta tile, the yurt, timbrel vaulting, or other “local knowledge” or “local wisdom.”4 Instead, it was the efficacy of such methods—their low cost, ready availability, renewable and/or sustainable sourcing, relative ease of construction, and sensitivity to local climactic conditions—that justified their central place in the exhibition.

Industrial materials were few and far-between in Aravena’s exhibition. Plastics erupted only intermittently, often as part of a program to promote recycling or repurposing. Polish architect Hugo Kowalski and art critic Marcin Szczelina, for example, produced a didactic display about garbage and detritus that grew increasingly heaped with visitors’ plastic water bottles as the exhibition ran. Steel beams were almost nowhere to be seen. In fact, the only memorable presentation of steel came in the entryway to the Arsenale venue for Aravena’s curated exhibition. In the theatrical opening space of the Arsenale, the former warehouse’s rough brickwork was subsumed by stacks of plaster boards (recycled shipping material from the previous year’s Art Biennale), while long metal studs (also recycled from the previous Biennale) loomed down from the ceiling, filling the gallery space from the high ceiling until a point shortly above viewers’ heads.5

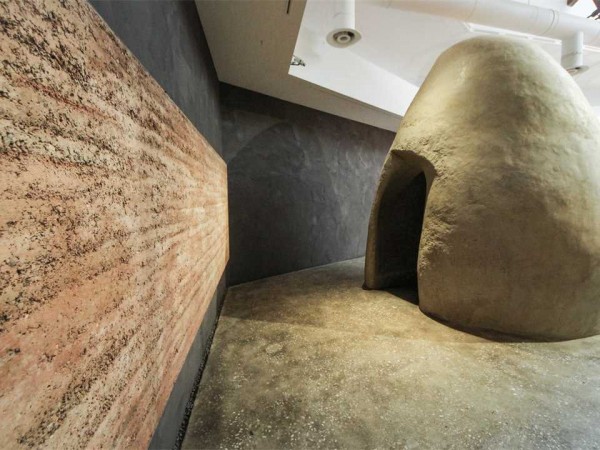

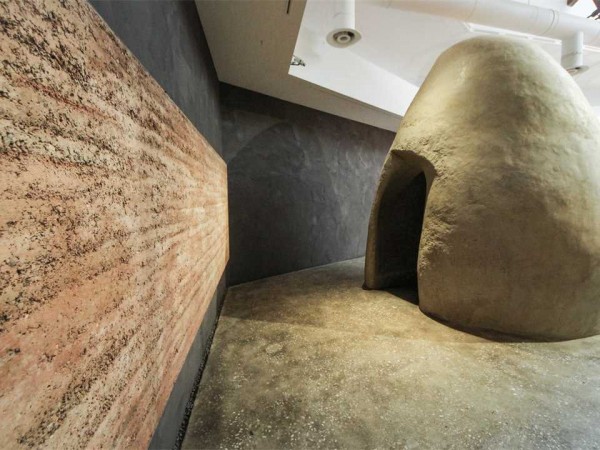

The most prevalent substances were mud, rammed earth, terra-cotta tiles, and wooden piers, promoted as “local materials.”6 For example, the project of Indian architect Anupama Kundoo consisted primarily of an elegant exploration of materials. Spread across a room of tables around chest height, chunks of wood and heaped raw earth pigments looked as if they had escaped from an Hélio Oiticica assemblage. The Chinese architects Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu, of Amateur Architecture, arranged strips of reclaimed construction materials in shin-high wooden frames, organizing them in a rough grid just inside the entrance to the Arsenale exhibition. In room after room, materials drawn from the earth were privileged in place of industrial materials, e.g., (imported) steel. A collaboration among German architect Anna Heringer, Austrian architect Martin Rauch, and German architectural critic Andres Lepik installed a womb-like, hand-molded earth and mud enclosure and a rammed-earth wall alongside a wall of infographics that traced the history of mud construction and the contemporary building codes that currently restrict its use.7

But if there was one single material that dominated the exhibition it was not the earth and clay that seemed ever-present, but concrete. Even the handful of high-rise office buildings relied heavily upon that “mongrel” material already known to the Romans.8 In a recent Russian design for a troubled, quasi-government-sponsored tech campus, reinforced concrete slabs in various shapes comprised a matryoshka doll-like shell nestled inside a pyramidal envelope, offering a lazy riff on national symbols.9 For the TID Tower complex in Tirana, Brussels-based 51N4E had to abandon their Western European reliance on standardized, pre-cast forms, and instead drew upon Albanian “magicians of cast-on-site concrete.”10

However, what went largely unacknowledged amongst this celebratory stance was that the use of artisanal materials and methods almost invariably necessitates cheap and abundant labor. When this unpaid or underpaid labor was mentioned, it was celebrated, as with Paraguayan architect Solano Benitez’ work with “two of the most available materials—bricks and unqualified labor—as a way to transform scarcity into abundance.”11 Another notable case was the installation by Ecuadorian studio Al Borde Arquitectos, which presented stacks of money corresponding to the cost per square meter of nine buildings from across the globe, with the intimation that the disparity between building costs in Europe and Latin America reflected poorly on European profligacy rather than lack of regulations, worker protections, and wage differentials elsewhere around the world.12 The sustainable and the local thus become buzzwords that papered over or assuaged the inequities of global economic flows. Behind the visible materials, one must ask: Who built it? Who paid for it? and Who profits?

Labor

Ostensibly, the TID Tower complex was included in Aravena’s exhibition due to its sensitive treatment of the tomb of Suleiman Pasha, Tirana’s founder. The tomb was tucked beneath a parabolic void in one of the complex’s low-slung concrete buildings. The central TID Tower rose from a elliptical base to a rectangular top, the TID tower maximized floorspace on the upper levels while leaving room at street level for a pleasant pedestrian walkway space set with cafe tables, or so a related promotional video depicted. The tower’s client (they paid for it) was the Tirana International Development sh.p.k., a limited liability corporation “founded in 1998, of entirely Albanian Capital.”13 At the Venice Architecture Biennale, the 51N4E installation was sponsored by the Belgian company Reynaers Aluminum (slogan, “Together for Better.”), which presented “a large scale model [of the TID Tower] with a movie and a publication which will function as an introduction to the city of Tirana, as well as to the numerous projects that emerged in the wake of the tower.”14

Aravena must have know how transparently this read as corporate promotion, as the 51N4E project was tucked in a corner of the Arsenale that was easy to miss after the drama of the exhibition’s opening rooms. Passing beneath the dramatic hanging steel beams in the first room of the Arsenale, two temporary walls guided viewers into a space dominated by a field of low, plinth-like containers filled with the grids of building materials reclaimed by Chinese architects Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu of Amateur Architecture Studio.15 Positioned behind this chute that propelled visitors from Aravena’s cave to Wang and Lu’s spotlit plinths, the 51N4E video was thus largely ignorable.

Yet Aravena’s instincts were spot on with the Tirana project. This is not because 51N4E offered a particularly sensitive approach to local conditions, as suggested by the architects’ discussion of creating a building responsive to Tirana’s “superb and slightly surreal” Mediterranean light and Albania’s majority Muslim populace.16 In fact, reading 51N4E’s take on Tirana, one cannot help but recognize the themes of Aravena’s Biennale in the relationship between the Brussels architects and their Albanian clients and laborers. Prior to beginning the project, 51N4E assumed a level of regulation and type of professionalization lacking in Albanian construction and urban development, finding instead that, “[E]xecution drawings had little meaning in this context, other than preparing legal documents for the sake of the local municipal authorities. On the other hand the contractors had an unseen 1:1 relationship with the actual building material, which opened up new possibilities.”17 Rather than a learned and technologized relationship to construction, the Albanian laborers ostensibly had an intuitive, almost pre-technical grasp of materials, in keeping with the Biennale’s emphasis on local (vernacular) knowledge. However, “The final decision for an Albanian production facility was triggered by the need to establish a low-cost production environment. In Albania each panel costs about 500 Euro, in Belgium it would cost 1.500 Euro.”18 As one can see, the Biennale’s emphasis on local materials encompassed the use of local, low-cost labor as well.

In Aravena’s Biennale, even buildings constructed using seemingly typical materials deployed non-professional labor, in which many projects were completed by their end users. Despite the utopian potentialities of participatory design, what became clear throughout the Biennale was the extent to which “social architecture” must justify itself by incorporating the labor of its beneficiaries or inhabitants. Aravena himself won the Pritzker Prize in 2016 largely in recognition for his incremental urbanist projects in Chile, including houses in the tsunami-ravaged city of Constitución. A typical approach to social housing situates homes far from city centers and jobs, an isolation of economically marginalized populations at urban peripheries that Aravena has called “the drama of Latin America.”19 In contrast, Aravena has promoted an incremental urbanism, or “half-a-house” model, in which government subsidies are used to construct part of a residence (typically roof, kitchen, bathroom, and basic structure) while residents contribute their own resources to completing the remainder (individual bedrooms and living spaces).

One pragmatic example of incremental urbanism in Aravena’s exhibition was the “Grundbau und Siedler” [Base and Settlers] project commissioned by PRIMUS developments GmbH and Manfred König in Hamburg, Germany, as well as the Neubild—On Königsberger Strasse and Aleppoer Weg [Königsberg Street and Aleppo Way] proposal by BeL Architects of Berlin. Both the built project and proposal were intended to address the housing needs of migrants to Germany by constructing a “neutral frame of beams, slabs, and columns” that could be “completed and modified by the owner later on.”20 One can imagine—though this was not elucidated in BeL’s proposal—that the migrants’ completion of their own housing would require engagement with local vendors of building materials or possibly training in the trades that could incorporate German language learning. By constructing a “basic geometry” and “basic services such as water, sewage, and electricity,” and allowing migrants to complete individual apartments rooted in “the cultural background of people who occupy them,” the projects thus had the potential to offer meaningful social integration for migrants for whom housing would be delivered as incremental urbanism.21

Architecture will increasingly need to be a practice of designing infrastructure rather than buildings. Within architect-designed infrastructure or “basic geometries,” non-architects (contractors or civilians) can construct shelters from available materials using vernacular techniques. Of course, this is not a new idea, since numerous architects explored similar ideas with the megastructures of the 1960s and 1970s.22 One also finds precedents for this sort of incremental urbanism in Walter Segal’s self-build model in 1970s Britain, roughly contemporaneous sweat equity programs in the U.S., and contemporary Habitat for Humanity construction.23 However, if the non-architects involved in these earlier cases typically constructed individual domestic structures or rehabbed residences within apartment buildings, one can sense a coming Metabolist future in which individuals are more generally responsible for building their own cities.24

Free Labor

But such self-build models are not without problems. Firstly, as Aravena himself points out, self-build is already a reality for some 90% of the world’s population who “are in actual fact authors of the places where they live—we call them slums.”25 More perniciously, perhaps, requiring end-users or clients or recipients of social welfare (depending upon how one wants to categorize them) to contribute their own labor to construct housing is part and parcel of a neoliberal expectation that individual willpower, entrepreneurship, and resources will eventually trump communitarian models of economic relations.

Ambivalence towards the status of the expert (the architect) is also pervasive in Aravena’s exhibition. A certain authoritarianism can even creep in, as with the Swiss village of Monte Carasso, to which architect Luigi Snozzi essentially offered his design services for free, in exchange for an exceptional level of control over the entire urban plan over the course of five decades.26 In streamlining the the town’s building codes from 240 articles to just seven, for example, Snozzi explained article three as, “Three local architectural experts must be nominated for a commission that will examine al projects. Considering how difficult it is to find experts, I propose s the commission be made up of only one expert—me.”27 This was presented with a largely celebratory tone, failing to acknowledge the anti-democratic relationship between architect and clients.

Another egregious example, this one in the national pavilion portion of the Biennale (thus NOT curated by Aravena), was the sort of millennial hipster totalitarianism of the Hungarian Pavilion. Chosen through an juried open competition within Hungary, a studio of young architects exhibited their “sustainable model” of development, in which they remodeled a disused building in the small village of Eger into an arts space called Artistic Supply.28 What was “sustainable” about the process was its financing. After being granted a 15-year lease on the building from the local government, materials were recycled from the building itself or donated by contacts in the local construction industry.29 The actual construction work drew upon a local polytechnic high school, with youth apprentices able to train and practice building trades in the process of rehabbing the building. But these architects went one step further, involving a local prison population as laborers on the project.30 With no sense of the ethical implications of employing prison labor—for one Hungarian interviewer this signified that “the local community actually built it [Artistic Supply]”—the Hungarian pavilion sunnily showcased inmates’ delight in being able to leave confinement and enjoy satisfying work with their hands.31

Though such a stark ethical dilemma was not present in the portion of the Biennale curated by Aravena, Aravena’s exhibition largely failed to acknowledge the economic structures that enabled—or prevented—the construction of the architectural projects on display. In fact, one of the striking aspects of the Biennale was the prevalence of grade schools—the fifty schools built by architect Luyanda Mpahlwa in rural South Africa, the “open outdoor classrooms” by Chilean architectures Alton and Léniz in the Andes, and the dozen or so schools by C+S studio in northern Italy—as building projects around which it is perhaps less challenging to build consensus among governments and their tax payers.32 Overall, the types of buildings included in the exhibition were largely noncommercial, and instead one found predominantly social housing, transportation infrastructure, and schools in places with strong state investment.

Tellingly, only a single United States-based practice was featured in the portion of the Biennale curated by Aravena. This was not, however, a polemical displacement of U.S. hegemony in favor of marginalized lifeways of the Global South, but a result of Aravena’s emphasis on social architecture. Social architecture, understood as a subset of architectural practice that “foreground[s] the moral imperative to increase human dignity and reduce human suffering,” is funded predominantly by governments, charitable foundations, NGOs, and aid organizations.33 Such funding structures are often secondary or even absent in the U.S., where the market reigns supreme.

The single U.S. practice included in the exhibition, the Alabama-based Rural Studio, is an exception that proves the rule. Focused on the U.S.’s own internal Global South, the Deep South of rural Alabama, Rural Studio is housed within and funded by a private higher educational institution, Auburn University. This mode of funding, via university tuition and fees, charitable contributions to the university, and donated labor of students, is an anomaly in the largely market-driven world of architecture in the U.S. Despite its utopian aspirations, and even marketing, Rural Studio’s participants freely admit that it fails to intervene in a longer history of government disinvestment and economic challenges in this region.34 Of course, this is perhaps too much to expect from an educational program. Of greater interest here is the way that Rural Studio exemplifies Aravena’s overall exhibition program. Like many of the projects in Aravena’s exhibition, Rural Studio remains wedded to the idea of home ownership as the ultimate goal. Moreover, it fails to acknowledge the histories that make possible the plethora of white, middle-class university students donating their labor to house impoverished rural black Alabamans, with the students themselves gaining cachet through their association with social architecture.

Form

As with the use of materials, many architects based forms on local topographical features or climactic exigencies. Architect David Chipperfield’s visitor’s center at the archaeological site of Naqa (or Naga’a) in Sudan was a bunker-like building of compressed concrete “with local sand and aggregates using traditional techniques,” and a prefab brick-tile roof.35 With no visible power or water lines leading to, the building mockup site isolated in the midst of desert landscape, paralleling the plateaus beyond. But beyond the naturalistic relationship to topos, the project presentation was supplemented with a series of large-scale, full-body photographs and mini-biographies of Sudanese citizens of different races, ages, and social classes. This was not a window onto the building’s users, however, since many of the people stated that they were unlikely to go to the visitor’s center. Instead, local people were used to authenticate the building, with their very bodies serving to bolster narrative accounts of the Sudanese setting to exhibition goers. Here we see a classic architectural deployment of the “vernacular,” linked to the figure of “the other, a pure and natural man, in contrast to a Western man corrupted by the turmoil of the nineteenth [read twenty-first] century.”36

But if there was a single architectural form that characterized the 15th Architecture Biennale, it was the Catalan vault (also called the timbrel vault), a soaring, double-curve structure traditionally constructed in earth tiles. The roofs of these vaulted structures form dramatic curves that seem to float with no visible support (no columns). At the same time, with no angle distinguishing roof from wall, the very top of the structure is linked to the ground in one uninterrupted curve, as if the soaring roofline curve is loosely pinioned to the earth at key junctures.37 The effect is airy like the vaulted ceiling of a cathedral, but the continuity between roof and walls evokes a tent tethered to the ground.

In the first gallery space of the Giardini exhibition hall, Paraguayan architect Solano Benítez’ Gabinete de Arquitectura studio had pride of place with a spectacular unreinforced vault formed of brick.38 Inside the Arsenale, the ETH Zurich-affiliated Block Research Group, along with John Ochsendorf, Matthew DeJong and The Escobedo Group, exhibited an immense mortarless vault made of stacked limestone. While these were the only two true vaults contained within the gallery spaces, there were a number of other structures whose forms echoed the curved ceiling of the vault and its tent-like connection to the earth. Simón Vélez presented a soaring bamboo dome, while Anupama Kundoo exhibited models and photographs of several experiments with vaulted terra-cotta and ferro-cement structures.39 Among the tent structures were several yurts based on hybrid nomadic-sedentary housing in Ulaanbaater, exhibited by the University of Hong Kong’s Rural Urban Framework.40 Additionally, positioned just before the entrance to the Giardini exhibition hall was a tent “derived from the typical tents of the [refugee] camps” that acted as the national pavilion of the Western Sahara.41 Across disparate materials and forms, the Biennale reiterated the “concave and intimate space” characteristic of the timbrel vault, with curved ceilings and arches that reach from ceiling to floor. Throughout the Biennale, structures combined the vertical heights of sacred monumental architecture with the domestic coziness of tent structures.42

BBHMM Moo-la-lah

The 15th Venice Architecture Biennale and many of its participants also enjoyed the support of a shadow patron, the LafargeHolcim Foundation for Sustainable Construction (formerly known as the Holcim Foundation for Sustainable Construction).43 Aravena himself had been awarded a Holcim Awards Silver in 2011 for post-tsunami housing in Constitución, Chile, and he has served on the foundation’s board since 2013.44 The portion of the Biennale curated by Aravena was heavily tilted toward projects connected in some way to the LafargeHolcim foundation; many of the architects had been recognized by LafargeHolcim, and numerous projects had received LafargeHolcim awards. Aravena claimed that it came as a surprise to him, after choosing participants in the curated portion of the Venice Architecture Biennale, to find that a number of them had received awards from the LafargeHolcim Foundation.45

But an even more insidious presence at the Venice Biennale was the for-profit building materials company LafargeHolcim (trading as LHN on on the SIX Swiss Exchange and Euronext Paris, and HCMLF as an OTC trade the United States). The sole sponsor of the LafargeHolcim Foundation, LafargeHolcim Ltd, is a building materials company formed in 2015 from the merger of two of the world’s biggest cement companies, the French Lafarge SA and the Swiss Holcim Ltd.

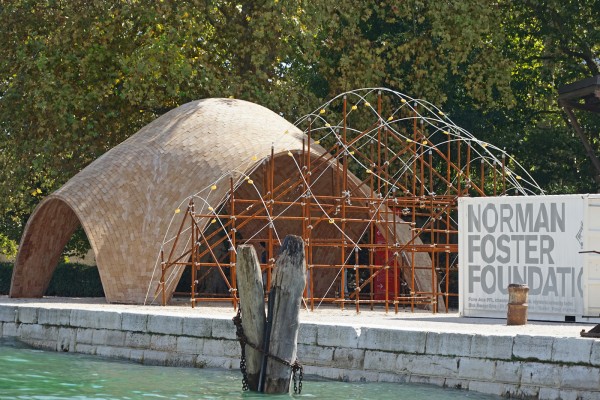

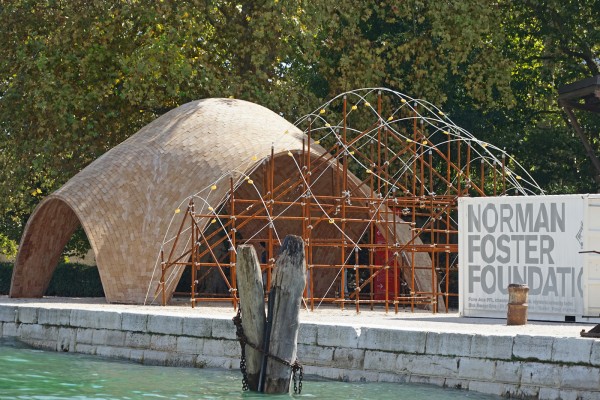

Do not, however, imagine that LafargeHolcim Ltd merely provided funding for the LafargeHolcim Foundation’s activities, which indirectly supported several practitioners included in the Venice Architecture Biennale. LafargeHolcim Ltd was itself a highly visible presence on the dock area outside the Arsenale venue of the Biennale. There, a brick tile timbrel vault visualized a new initiative spearheaded by British architect Norman Foster’s own eponymous foundation: the Droneport project.

The proposal is to create a network of drone ports to deliver medical supplies and other necessities to areas of Africa that are difficult to access due to a lack of roads or other infrastructure and the ambition is that every small town in Africa and in other emerging economies will have its own droneport by 2030.46

What made this an architectural rather than humanitarian or development project was not only because it was spearheaded by architect Norman Foster, but because of the eye catching formal statement his Droneport made. Drawing upon the historical technique of the timbrel [tambourine] vault, also known as the Catalan vault for its widespread use in early modern Catalonia, the droneport articulated a set of graceful curves against the backdrop of Venice’s waterways.47 The Block Research Group at the ETH Zurich provided their knowledge of structural engineering, leading to an “optimized vault form,” while the LafargeHolcim Foundation beneficently provided support for construction of this prototype droneport at the Venice Architecture Biennale. But it was LafargeHolcim Ltd’s R&D laboratory in L’Isle d’Abeau, France, that developed the key material substrate for the Droneport: a lightweight hand-machined compressed earth and cement tile they call DuraBric. LafargeHolcim was heralded for developing this composite, which could potentially rely on earth near each construction site for roughly 90% of its material, thus eliminating the cost and effort of importing industrial materials like steel to remote areas of underdeveloped Africa. Yet it is not LafargeHolcim Foundation that would supply DuraBrics, but LafargeHolcim Ltd.

Moreover, as architectural historian George R. Collins has asserted,

It should be noted that the elements of these [timbrel] vaults are not held together by friction produced by pressure of the elements against each other under the force of gravity . . . ; instead the tiles are simply “stuck” together by a mortar so tenacious that tiles will ordinarily break or split before the mortar parts. . . . The mortar is not simply a bed for the joints of large stone voussoirs; it is a thick blanket around and amongst the tiles, constituting approximately 50 per cent of the masonry so that the whole becomes, as it were, a sort of concrete made with an aggregate of highly regular pieces—the tiles.48

The local earth of the tiles is practically suspended in an emulsion of cement.49 Thus LafargeHolcim, one of the largest cement manufacturers in the world, and also known as an industry leader in aggregates, supports a novel construction method for what may come to be an indispensable civic building worldwide. That construction method utilizes cement and the proprietary DuraBric tile, both sold by LafargeHolcim Ltd. Beyond good publicity, this has the potential to be good business.

The beneficence of the LafargeHolcim Foundation, all the while failing to mention—or downplaying to an absurd degree—the crucial role of the for-profit LafargeHolcim company, supposedly the largest manufacturer of building materials in the world, It is the for-profit LafargeHolcim that would be responsible for making the DuraBrics for constructing DronePorts, and supplying the cement for mortaring thousands of DronePorts—not just in Africa, but around the world. No mention, then, of who would pay for the eventual construction of these thousands of DronePorts, nor the millions of francs that would flow to LafargeHolcim. A small-scale publicity stunt, a generous funding of several small DronePorts, would kick off a worldwide investment in an entirely new transportation infrastructure in which LafargeHolcim would be, if not the only supplier of a crucial building material, certainly the preeminent supplier for a long time to come. Money makes the world go round.

Aravena’s entire Biennale, then, its emphasis on “natural” materials—the omnipresence of earthen brick and tile—its insistence on the collaboration among state and humanitarian actors, all lead to the quayside behind the Arsenale, to a Catalan vault through which a starchitect advances his brand and a global conglomerate advances its sales.

But the Droneport also offer a particularly insidious relationship among architecture, international development, and warfare. The Droneport project is spearheaded by The Norman Foster Foundation and Jonathan Ledgard, a former journalist who recently stepped down as director of Afrotech, an African development research center at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL).50 As the two men describe it, this drone network will eventually span a huge swathe of sub-Saharan Africa, though current efforts are concentrated on Ledgard’s so-called Redline project in Rwanda. The Redline will consist of a system of Droneports to transport medical and emergency supplies throughout the country of Rwanda, with the Rwandan government projected to pay one third of the cost of the initial network.51 With its small land area, densely-settled population, Western-educated and Anglophone elite, extensive network of fiber-optic internet cables, and post-genocide openness to foreign investment, Rwanda would seem like a natural starting point for the Droneport project.52 However, there is also the crucial matter of Rwanda’s relationship to its eastern neighbor, the Congo.53

A resource-poor yet densely populated country, Rwanda draws a large proportion of its budget from international aid while also drawing—both legally and illicitly—on the sale of Congolese minerals, including gold, diamonds, and metals such as coltan, an amalgam crucial for smart phones.54 In 2012-2013, the United States and the United Kingdom partially withheld aid to Rwanda as a rebuke for its involvement in armed conflict in the eastern Congo.55 Yet by 2015, funding had reached new heights, with the U.S. providing $247 million in aid to Rwanda, not including military aid, while the United Kingdom contributed roughly £70 million—this compared to Rwanda’s annual tax revenues of roughly $1.1 billion in 2015/2016.56 With roughly half of Rwanda’s national budget made up of aid from the U.S. and the U.K., one might consider the Rwandan government less as an enthusiastic backer of Norman Foster’s Droneport project and more as a conduit for British (and perhaps U.S.) investment in a drone network in Africa.57

That said, the Rwandan government’s strong control on its territory—including suppression of opposition parties, voter intimidation, reeducation camps that are compulsory for university matriculants, restrictions on freedom of speech, and centralized control of the economy under the guise of a private company held entirely by the current ruling party—means that the drone network will necessarily operate with considerable government oversight if not outright control.58 One glance at the proposed Droneport map reveals that the densest network of Redline routes is oriented along Rwanda’s border with the Congo, offering a multitude of opportunities for surveillance or even deployment of drones as weaponry in ongoing small-scale incursions into the Congo.59 From the very first, it was imagined that the drone project would soon expand into the Congo.60

Of course, even if this is not a priority—and, indeed, militarization would be a horrifying thought—for international development agencies backing the Droneport project, there is still the matter of profit motive. Alongside the Redline humanitarian drone network, Normal Foster’s foundation has also mooted the idea of a commercial Blueline “that would transport crucial larger payloads such as spare parts, electronics, and e-commerce, complementing and subsidising the Redline network.”61 Here one finds the holy grail for contemporary investment, the vast untapped mass of potential consumers in Africa, now hampered not only by economic misery but also by the inability for goods to reach market. In a philanthropic sense, drones with payloads of one hundred kilograms could allow agricultural producers to send goods to additional markets and potentially earn higher incomes.62 But more to the point for Western investors, drone-backed e-commerce could instantly reach hundreds of millions of consumers in sub-Saharan Africa.

In fact, an early report on the Droneport project foregrounded its commercial prospects: “Rwanda Plans Airport for E-Commerce Drones.”63 Moreover, even humanitarian drone deliveries would likely be imbricated within the health care tech industry. Already, blood and vaccines are being delivered across Rwanda by the for-profit California-based company Zipline, paid per delivery by the Rwandan government.64 With “$19 million in venture capital from investors including Sequoia Capital, Google Ventures, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, Yahoo co-founder Jerry Yang, and Subtraction Capital,” Zipline chose Rwanda as a test site for their drone deliveries based on a tip from the Redline’s Jonathan Ledgard. Now, the U.S. government is interested in copying the model for rural healthcare. As Killian Doherty’s excellent Thinkpiece in Architectural Review describes, the Droneport thus exemplifies the problem of “humanitarian architecture that is paradigmatically prone to being heavily narrated out of context, particularly the political context, and in a manner that distorts a view of the charged spaces of development as neutral.”65

Social (?) Architecture

Thus the Droneport offers the culmination of Aravena’s exhibition: in its materials (earthen tiles), in its forms (a tent-like shelter), and in that the humanitarian aspects of “social architecture” are necessarily implicated in ulterior motives on the part of stakeholders. At the risk of finding nefarious ends wherever an architectural project involves profit, it is necessary to understand how “the logic of real estate development under capitalism” underlies much of Aravena’s exhibition.66 Here we see why—despite the presence of so much government investment—this is not properly a biennale of “civic” or “public” architecture. The term “social” muddies the water just enough, introducing priorities that may conflict with the collective as administered by a state, or that project a transnational network of people—and, by extension, capital. It is this underlying thematic that differentiates Aravena’s exhibition from its predecessor, Andres Lepik’s 2010 exhibition Small Scale Big Change: New Architectures of Social Engagement, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.67

The market is omnipresent in this Architecture Biennale, with ownership at the heart of even the most “social” architectural projects. With a project for a French social housing apartment building, the architects’ language reiterated a normative (if not entirely puritanical) cycle of the nuclear family as “living together, marriage, children, and old age.”68 The presentation even had dollhouse-like models of domestic interiors and portraits of the inhabitants amidst the stuff of their new apartments, a vision of domestic nesting embodying a petit bourgeois aspiration to home ownership.69 At a Biennale panel discussion sponsored by LafargeHolcim, Aravena himself was even more explicit about the links between social architecture and private property (which may, in fact, be less relevant in the case of French social housing). Explaining his work in Chile, Aravena situated himself as part of a lineage reaching back to the Chilean government’s formalization of squatters’ plots in the 1970s, when “Operation Chalk,” enabled people to stake ownership over plots of land using chalk lines.70 The lines established “property structure and nothing more than that, just the geometry of who would own what, meaning this will be a street, this will be a private lot.”71 Or, as The New York Times Style Magazine explained of Aravena’s recent work in Constitución, “Residents of Villa Verde [in Constitución], who had next to nothing, gain equity.”72 Within Aravena’s vision of social architecture, there is always already private property to which we should aspire. This is not to say that humanitarian or social architectures should never involve the market, but that one must remain aware of the webs of capital and political motives that allow such architectures to exist.73

In this outsider biennale, finally, the relationship between architect and non-architect was left largely implicit. One notable exception can be found in comments by Sri Lankan architect Melinda Pathiraja during a panel discussion on sustainability and security.74 Pathiraja openly proclaimed the perhaps unfashionable view that experts are a necessary part of architecture, especially in the Global South. In Sri Lanka, Pathiraja asserted, less than a fraction of 1% of buildings were constructed under the auspices of architects, leading to a number of problems in safety and durability. One can quibble with the nature of the experts who could best address this perceived lack—wouldn’t engineers be just as useful as architects in preventing structural defects?—and find fault with the power relations implicit in this call for architects. However, Pathiraja’s point is well taken. We might simply rephrase it not as a call for experts, but as a call for expertise.

And here is where Aravena’s Biennale does a great service to the profession, in calling for a reevaluation of what constitutes expertise in the field of architecture. Rather than highlighting pre-industrial building techniques as a way to reinvigorate folkloric nationalisms, the exhibition fiercely defends the prowess of these techniques in their own right. These techniques are important not because they are native or traditional, but because they are functional.

At the same time, Aravena’s Biennale provides a roadmap for a pernicious neoimperialism in which extractive processes are applied to local knowledge as well as raw materials. Longstanding and little-monetized expertise such as the timbrel vault and Saharan tent are studied in situ, then analyzed using advanced technology (e.g., “Thrust Network Analysis (TNA), a technique developed over the last ten years by the MIT and the ETH Zurich”). Finally, they are re-imported to their sources, this time with the caveat that local practitioners need the assistance of foreign experts in order to implement what was once local knowledge. Here, then, we return to the Maria Reiche ladder story, and the problematic position of the expert—the architect—implicit in Aravena’s Biennale. In Aravena’s South American fable, a German archaeologist, with her metal industrial tool, is the one to “make sense” of the landscape, to apprehend its secrets and potentialities, and thus to re-narrate the histories of the Peruvian desert to its inhabitants. But with the Droneport, architecture offers a more insidious intervention in global flows. A British lord uses Swiss digital technology to “optimize” mud tile vaults, a humanitarian window dressing as Western companies literally remap the African continent.

Notes

Curated by Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale (May 28-November 27, 2016) focused on architectures that addressed large-scale problems using vernacular techniques.1 If the implicit theme of the 2013 Venice Art Biennale had been “outsider art,” characterized by Daily Telegraph critic Alistair Sooke as both “visionary” and “homespun,” the similarly unstated theme of this 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale can be understood as outsider architecture.2

Aravena’s Architecture Biennale foregrounded the outsider in two senses. Rather than a capital-intensive architecture of improbable forms and futuristic substances, set in cosmopolitan cities of the developed West, Aravena’s exhibition emphasized natural materials and labor-intensive techniques common to the Global South. What went unspoken, however, was the relationship between architecture’s insiders and its outsiders, between capital and labor, between the developed world and its other.

The image that Aravena chose for the exhibition collateral exemplified this problematic. On posters, banner ads, and catalogue covers, one found an image of an older woman on a ladder, set against a bright blue sky in an arid, unmarked landscape. In explaining the image, Aravena adopted a fable-like tone:

In his trip to South America [British travel writer] Bruce Chatwin encountered an old lady walking the desert carrying an aluminum ladder on her shoulder. It was German archeologist Maria Reiche studying the Nazca lines. Standing on the ground, the stones did not make any sense; they were just random gravel. But from the height of the stair those stones became a bird, a jaguar, a tree or a flower.3

Within the seemingly empty landscape of the Global South, a German scientist with her industrial tool (an aluminum ladder) analyzes the landscape; she “makes sense” of its secrets and potentialities. The image is an apt allegory for the current state of architectural interest in traditional or vernacular modes: non-expert architectural knowledge is extracted, repackaged and cloaked in the language of technology and sustainability, then re-learned back at its source. The problem of Aravena’s exhibition is not, though, reducible to a rather simplistic accusation of cultural appropriation. Instead, the crux of this Venice Architecture Biennale lies in its emphasis on so-called “social architecture,” even as it fails to question the socio-economic situations within which architects operate. In its implicit relationship of native, local, or vernacular resources to foreign, technological expertise, the fable of Maria Reiche undergirds the whole of Aravena’s exhibition. However, Aravena updates the fable, with the exhibition’s social architetures and vernacular forms culminating in a contemporary twist: a new neoimperial project for a network of drones across Africa.

Materials

Aravena should be commended for refusing a nostalgic or folkloric frame for traditional, “low-tech” construction techniques and materials. At no point were national mythologies or romantic visions of premodern communities invoked to validate the use of rammed earth, terra-cotta tile, the yurt, timbrel vaulting, or other “local knowledge” or “local wisdom.”4 Instead, it was the efficacy of such methods—their low cost, ready availability, renewable and/or sustainable sourcing, relative ease of construction, and sensitivity to local climactic conditions—that justified their central place in the exhibition.

Industrial materials were few and far-between in Aravena’s exhibition. Plastics erupted only intermittently, often as part of a program to promote recycling or repurposing. Polish architect Hugo Kowalski and art critic Marcin Szczelina, for example, produced a didactic display about garbage and detritus that grew increasingly heaped with visitors’ plastic water bottles as the exhibition ran. Steel beams were almost nowhere to be seen. In fact, the only memorable presentation of steel came in the entryway to the Arsenale venue for Aravena’s curated exhibition. In the theatrical opening space of the Arsenale, the former warehouse’s rough brickwork was subsumed by stacks of plaster boards (recycled shipping material from the previous year’s Art Biennale), while long metal studs (also recycled from the previous Biennale) loomed down from the ceiling, filling the gallery space from the high ceiling until a point shortly above viewers’ heads.5

The most prevalent substances were mud, rammed earth, terra-cotta tiles, and wooden piers, promoted as “local materials.”6 For example, the project of Indian architect Anupama Kundoo consisted primarily of an elegant exploration of materials. Spread across a room of tables around chest height, chunks of wood and heaped raw earth pigments looked as if they had escaped from an Hélio Oiticica assemblage. The Chinese architects Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu, of Amateur Architecture, arranged strips of reclaimed construction materials in shin-high wooden frames, organizing them in a rough grid just inside the entrance to the Arsenale exhibition. In room after room, materials drawn from the earth were privileged in place of industrial materials, e.g., (imported) steel. A collaboration among German architect Anna Heringer, Austrian architect Martin Rauch, and German architectural critic Andres Lepik installed a womb-like, hand-molded earth and mud enclosure and a rammed-earth wall alongside a wall of infographics that traced the history of mud construction and the contemporary building codes that currently restrict its use.7

But if there was one single material that dominated the exhibition it was not the earth and clay that seemed ever-present, but concrete. Even the handful of high-rise office buildings relied heavily upon that “mongrel” material already known to the Romans.8 In a recent Russian design for a troubled, quasi-government-sponsored tech campus, reinforced concrete slabs in various shapes comprised a matryoshka doll-like shell nestled inside a pyramidal envelope, offering a lazy riff on national symbols.9 For the TID Tower complex in Tirana, Brussels-based 51N4E had to abandon their Western European reliance on standardized, pre-cast forms, and instead drew upon Albanian “magicians of cast-on-site concrete.”10

However, what went largely unacknowledged amongst this celebratory stance was that the use of artisanal materials and methods almost invariably necessitates cheap and abundant labor. When this unpaid or underpaid labor was mentioned, it was celebrated, as with Paraguayan architect Solano Benitez’ work with “two of the most available materials—bricks and unqualified labor—as a way to transform scarcity into abundance.”11 Another notable case was the installation by Ecuadorian studio Al Borde Arquitectos, which presented stacks of money corresponding to the cost per square meter of nine buildings from across the globe, with the intimation that the disparity between building costs in Europe and Latin America reflected poorly on European profligacy rather than lack of regulations, worker protections, and wage differentials elsewhere around the world.12 The sustainable and the local thus become buzzwords that papered over or assuaged the inequities of global economic flows. Behind the visible materials, one must ask: Who built it? Who paid for it? and Who profits?

Labor

Ostensibly, the TID Tower complex was included in Aravena’s exhibition due to its sensitive treatment of the tomb of Suleiman Pasha, Tirana’s founder. The tomb was tucked beneath a parabolic void in one of the complex’s low-slung concrete buildings. The central TID Tower rose from a elliptical base to a rectangular top, the TID tower maximized floorspace on the upper levels while leaving room at street level for a pleasant pedestrian walkway space set with cafe tables, or so a related promotional video depicted. The tower’s client (they paid for it) was the Tirana International Development sh.p.k., a limited liability corporation “founded in 1998, of entirely Albanian Capital.”13 At the Venice Architecture Biennale, the 51N4E installation was sponsored by the Belgian company Reynaers Aluminum (slogan, “Together for Better.”), which presented “a large scale model [of the TID Tower] with a movie and a publication which will function as an introduction to the city of Tirana, as well as to the numerous projects that emerged in the wake of the tower.”14

Aravena must have know how transparently this read as corporate promotion, as the 51N4E project was tucked in a corner of the Arsenale that was easy to miss after the drama of the exhibition’s opening rooms. Passing beneath the dramatic hanging steel beams in the first room of the Arsenale, two temporary walls guided viewers into a space dominated by a field of low, plinth-like containers filled with the grids of building materials reclaimed by Chinese architects Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu of Amateur Architecture Studio.15 Positioned behind this chute that propelled visitors from Aravena’s cave to Wang and Lu’s spotlit plinths, the 51N4E video was thus largely ignorable.

Yet Aravena’s instincts were spot on with the Tirana project. This is not because 51N4E offered a particularly sensitive approach to local conditions, as suggested by the architects’ discussion of creating a building responsive to Tirana’s “superb and slightly surreal” Mediterranean light and Albania’s majority Muslim populace.16 In fact, reading 51N4E’s take on Tirana, one cannot help but recognize the themes of Aravena’s Biennale in the relationship between the Brussels architects and their Albanian clients and laborers. Prior to beginning the project, 51N4E assumed a level of regulation and type of professionalization lacking in Albanian construction and urban development, finding instead that, “[E]xecution drawings had little meaning in this context, other than preparing legal documents for the sake of the local municipal authorities. On the other hand the contractors had an unseen 1:1 relationship with the actual building material, which opened up new possibilities.”17 Rather than a learned and technologized relationship to construction, the Albanian laborers ostensibly had an intuitive, almost pre-technical grasp of materials, in keeping with the Biennale’s emphasis on local (vernacular) knowledge. However, “The final decision for an Albanian production facility was triggered by the need to establish a low-cost production environment. In Albania each panel costs about 500 Euro, in Belgium it would cost 1.500 Euro.”18 As one can see, the Biennale’s emphasis on local materials encompassed the use of local, low-cost labor as well.

In Aravena’s Biennale, even buildings constructed using seemingly typical materials deployed non-professional labor, in which many projects were completed by their end users. Despite the utopian potentialities of participatory design, what became clear throughout the Biennale was the extent to which “social architecture” must justify itself by incorporating the labor of its beneficiaries or inhabitants. Aravena himself won the Pritzker Prize in 2016 largely in recognition for his incremental urbanist projects in Chile, including houses in the tsunami-ravaged city of Constitución. A typical approach to social housing situates homes far from city centers and jobs, an isolation of economically marginalized populations at urban peripheries that Aravena has called “the drama of Latin America.”19 In contrast, Aravena has promoted an incremental urbanism, or “half-a-house” model, in which government subsidies are used to construct part of a residence (typically roof, kitchen, bathroom, and basic structure) while residents contribute their own resources to completing the remainder (individual bedrooms and living spaces).

One pragmatic example of incremental urbanism in Aravena’s exhibition was the “Grundbau und Siedler” [Base and Settlers] project commissioned by PRIMUS developments GmbH and Manfred König in Hamburg, Germany, as well as the Neubild—On Königsberger Strasse and Aleppoer Weg [Königsberg Street and Aleppo Way] proposal by BeL Architects of Berlin. Both the built project and proposal were intended to address the housing needs of migrants to Germany by constructing a “neutral frame of beams, slabs, and columns” that could be “completed and modified by the owner later on.”20 One can imagine—though this was not elucidated in BeL’s proposal—that the migrants’ completion of their own housing would require engagement with local vendors of building materials or possibly training in the trades that could incorporate German language learning. By constructing a “basic geometry” and “basic services such as water, sewage, and electricity,” and allowing migrants to complete individual apartments rooted in “the cultural background of people who occupy them,” the projects thus had the potential to offer meaningful social integration for migrants for whom housing would be delivered as incremental urbanism.21

Architecture will increasingly need to be a practice of designing infrastructure rather than buildings. Within architect-designed infrastructure or “basic geometries,” non-architects (contractors or civilians) can construct shelters from available materials using vernacular techniques. Of course, this is not a new idea, since numerous architects explored similar ideas with the megastructures of the 1960s and 1970s.22 One also finds precedents for this sort of incremental urbanism in Walter Segal’s self-build model in 1970s Britain, roughly contemporaneous sweat equity programs in the U.S., and contemporary Habitat for Humanity construction.23 However, if the non-architects involved in these earlier cases typically constructed individual domestic structures or rehabbed residences within apartment buildings, one can sense a coming Metabolist future in which individuals are more generally responsible for building their own cities.24

Free Labor

But such self-build models are not without problems. Firstly, as Aravena himself points out, self-build is already a reality for some 90% of the world’s population who “are in actual fact authors of the places where they live—we call them slums.”25 More perniciously, perhaps, requiring end-users or clients or recipients of social welfare (depending upon how one wants to categorize them) to contribute their own labor to construct housing is part and parcel of a neoliberal expectation that individual willpower, entrepreneurship, and resources will eventually trump communitarian models of economic relations.

Ambivalence towards the status of the expert (the architect) is also pervasive in Aravena’s exhibition. A certain authoritarianism can even creep in, as with the Swiss village of Monte Carasso, to which architect Luigi Snozzi essentially offered his design services for free, in exchange for an exceptional level of control over the entire urban plan over the course of five decades.26 In streamlining the the town’s building codes from 240 articles to just seven, for example, Snozzi explained article three as, “Three local architectural experts must be nominated for a commission that will examine al projects. Considering how difficult it is to find experts, I propose s the commission be made up of only one expert—me.”27 This was presented with a largely celebratory tone, failing to acknowledge the anti-democratic relationship between architect and clients.

Another egregious example, this one in the national pavilion portion of the Biennale (thus NOT curated by Aravena), was the sort of millennial hipster totalitarianism of the Hungarian Pavilion. Chosen through an juried open competition within Hungary, a studio of young architects exhibited their “sustainable model” of development, in which they remodeled a disused building in the small village of Eger into an arts space called Artistic Supply.28 What was “sustainable” about the process was its financing. After being granted a 15-year lease on the building from the local government, materials were recycled from the building itself or donated by contacts in the local construction industry.29 The actual construction work drew upon a local polytechnic high school, with youth apprentices able to train and practice building trades in the process of rehabbing the building. But these architects went one step further, involving a local prison population as laborers on the project.30 With no sense of the ethical implications of employing prison labor—for one Hungarian interviewer this signified that “the local community actually built it [Artistic Supply]”—the Hungarian pavilion sunnily showcased inmates’ delight in being able to leave confinement and enjoy satisfying work with their hands.31

Though such a stark ethical dilemma was not present in the portion of the Biennale curated by Aravena, Aravena’s exhibition largely failed to acknowledge the economic structures that enabled—or prevented—the construction of the architectural projects on display. In fact, one of the striking aspects of the Biennale was the prevalence of grade schools—the fifty schools built by architect Luyanda Mpahlwa in rural South Africa, the “open outdoor classrooms” by Chilean architectures Alton and Léniz in the Andes, and the dozen or so schools by C+S studio in northern Italy—as building projects around which it is perhaps less challenging to build consensus among governments and their tax payers.32 Overall, the types of buildings included in the exhibition were largely noncommercial, and instead one found predominantly social housing, transportation infrastructure, and schools in places with strong state investment.

Tellingly, only a single United States-based practice was featured in the portion of the Biennale curated by Aravena. This was not, however, a polemical displacement of U.S. hegemony in favor of marginalized lifeways of the Global South, but a result of Aravena’s emphasis on social architecture. Social architecture, understood as a subset of architectural practice that “foreground[s] the moral imperative to increase human dignity and reduce human suffering,” is funded predominantly by governments, charitable foundations, NGOs, and aid organizations.33 Such funding structures are often secondary or even absent in the U.S., where the market reigns supreme.

The single U.S. practice included in the exhibition, the Alabama-based Rural Studio, is an exception that proves the rule. Focused on the U.S.’s own internal Global South, the Deep South of rural Alabama, Rural Studio is housed within and funded by a private higher educational institution, Auburn University. This mode of funding, via university tuition and fees, charitable contributions to the university, and donated labor of students, is an anomaly in the largely market-driven world of architecture in the U.S. Despite its utopian aspirations, and even marketing, Rural Studio’s participants freely admit that it fails to intervene in a longer history of government disinvestment and economic challenges in this region.34 Of course, this is perhaps too much to expect from an educational program. Of greater interest here is the way that Rural Studio exemplifies Aravena’s overall exhibition program. Like many of the projects in Aravena’s exhibition, Rural Studio remains wedded to the idea of home ownership as the ultimate goal. Moreover, it fails to acknowledge the histories that make possible the plethora of white, middle-class university students donating their labor to house impoverished rural black Alabamans, with the students themselves gaining cachet through their association with social architecture.

Form

As with the use of materials, many architects based forms on local topographical features or climactic exigencies. Architect David Chipperfield’s visitor’s center at the archaeological site of Naqa (or Naga’a) in Sudan was a bunker-like building of compressed concrete “with local sand and aggregates using traditional techniques,” and a prefab brick-tile roof.35 With no visible power or water lines leading to, the building mockup site isolated in the midst of desert landscape, paralleling the plateaus beyond. But beyond the naturalistic relationship to topos, the project presentation was supplemented with a series of large-scale, full-body photographs and mini-biographies of Sudanese citizens of different races, ages, and social classes. This was not a window onto the building’s users, however, since many of the people stated that they were unlikely to go to the visitor’s center. Instead, local people were used to authenticate the building, with their very bodies serving to bolster narrative accounts of the Sudanese setting to exhibition goers. Here we see a classic architectural deployment of the “vernacular,” linked to the figure of “the other, a pure and natural man, in contrast to a Western man corrupted by the turmoil of the nineteenth [read twenty-first] century.”36

But if there was a single architectural form that characterized the 15th Architecture Biennale, it was the Catalan vault (also called the timbrel vault), a soaring, double-curve structure traditionally constructed in earth tiles. The roofs of these vaulted structures form dramatic curves that seem to float with no visible support (no columns). At the same time, with no angle distinguishing roof from wall, the very top of the structure is linked to the ground in one uninterrupted curve, as if the soaring roofline curve is loosely pinioned to the earth at key junctures.37 The effect is airy like the vaulted ceiling of a cathedral, but the continuity between roof and walls evokes a tent tethered to the ground.

In the first gallery space of the Giardini exhibition hall, Paraguayan architect Solano Benítez’ Gabinete de Arquitectura studio had pride of place with a spectacular unreinforced vault formed of brick.38 Inside the Arsenale, the ETH Zurich-affiliated Block Research Group, along with John Ochsendorf, Matthew DeJong and The Escobedo Group, exhibited an immense mortarless vault made of stacked limestone. While these were the only two true vaults contained within the gallery spaces, there were a number of other structures whose forms echoed the curved ceiling of the vault and its tent-like connection to the earth. Simón Vélez presented a soaring bamboo dome, while Anupama Kundoo exhibited models and photographs of several experiments with vaulted terra-cotta and ferro-cement structures.39 Among the tent structures were several yurts based on hybrid nomadic-sedentary housing in Ulaanbaater, exhibited by the University of Hong Kong’s Rural Urban Framework.40 Additionally, positioned just before the entrance to the Giardini exhibition hall was a tent “derived from the typical tents of the [refugee] camps” that acted as the national pavilion of the Western Sahara.41 Across disparate materials and forms, the Biennale reiterated the “concave and intimate space” characteristic of the timbrel vault, with curved ceilings and arches that reach from ceiling to floor. Throughout the Biennale, structures combined the vertical heights of sacred monumental architecture with the domestic coziness of tent structures.42

BBHMM Moo-la-lah

The 15th Venice Architecture Biennale and many of its participants also enjoyed the support of a shadow patron, the LafargeHolcim Foundation for Sustainable Construction (formerly known as the Holcim Foundation for Sustainable Construction).43 Aravena himself had been awarded a Holcim Awards Silver in 2011 for post-tsunami housing in Constitución, Chile, and he has served on the foundation’s board since 2013.44 The portion of the Biennale curated by Aravena was heavily tilted toward projects connected in some way to the LafargeHolcim foundation; many of the architects had been recognized by LafargeHolcim, and numerous projects had received LafargeHolcim awards. Aravena claimed that it came as a surprise to him, after choosing participants in the curated portion of the Venice Architecture Biennale, to find that a number of them had received awards from the LafargeHolcim Foundation.45

But an even more insidious presence at the Venice Biennale was the for-profit building materials company LafargeHolcim (trading as LHN on on the SIX Swiss Exchange and Euronext Paris, and HCMLF as an OTC trade the United States). The sole sponsor of the LafargeHolcim Foundation, LafargeHolcim Ltd, is a building materials company formed in 2015 from the merger of two of the world’s biggest cement companies, the French Lafarge SA and the Swiss Holcim Ltd.

Do not, however, imagine that LafargeHolcim Ltd merely provided funding for the LafargeHolcim Foundation’s activities, which indirectly supported several practitioners included in the Venice Architecture Biennale. LafargeHolcim Ltd was itself a highly visible presence on the dock area outside the Arsenale venue of the Biennale. There, a brick tile timbrel vault visualized a new initiative spearheaded by British architect Norman Foster’s own eponymous foundation: the Droneport project.

The proposal is to create a network of drone ports to deliver medical supplies and other necessities to areas of Africa that are difficult to access due to a lack of roads or other infrastructure and the ambition is that every small town in Africa and in other emerging economies will have its own droneport by 2030.46

What made this an architectural rather than humanitarian or development project was not only because it was spearheaded by architect Norman Foster, but because of the eye catching formal statement his Droneport made. Drawing upon the historical technique of the timbrel [tambourine] vault, also known as the Catalan vault for its widespread use in early modern Catalonia, the droneport articulated a set of graceful curves against the backdrop of Venice’s waterways.47 The Block Research Group at the ETH Zurich provided their knowledge of structural engineering, leading to an “optimized vault form,” while the LafargeHolcim Foundation beneficently provided support for construction of this prototype droneport at the Venice Architecture Biennale. But it was LafargeHolcim Ltd’s R&D laboratory in L’Isle d’Abeau, France, that developed the key material substrate for the Droneport: a lightweight hand-machined compressed earth and cement tile they call DuraBric. LafargeHolcim was heralded for developing this composite, which could potentially rely on earth near each construction site for roughly 90% of its material, thus eliminating the cost and effort of importing industrial materials like steel to remote areas of underdeveloped Africa. Yet it is not LafargeHolcim Foundation that would supply DuraBrics, but LafargeHolcim Ltd.

Moreover, as architectural historian George R. Collins has asserted,

It should be noted that the elements of these [timbrel] vaults are not held together by friction produced by pressure of the elements against each other under the force of gravity . . . ; instead the tiles are simply “stuck” together by a mortar so tenacious that tiles will ordinarily break or split before the mortar parts. . . . The mortar is not simply a bed for the joints of large stone voussoirs; it is a thick blanket around and amongst the tiles, constituting approximately 50 per cent of the masonry so that the whole becomes, as it were, a sort of concrete made with an aggregate of highly regular pieces—the tiles.48

The local earth of the tiles is practically suspended in an emulsion of cement.49 Thus LafargeHolcim, one of the largest cement manufacturers in the world, and also known as an industry leader in aggregates, supports a novel construction method for what may come to be an indispensable civic building worldwide. That construction method utilizes cement and the proprietary DuraBric tile, both sold by LafargeHolcim Ltd. Beyond good publicity, this has the potential to be good business.

The beneficence of the LafargeHolcim Foundation, all the while failing to mention—or downplaying to an absurd degree—the crucial role of the for-profit LafargeHolcim company, supposedly the largest manufacturer of building materials in the world, It is the for-profit LafargeHolcim that would be responsible for making the DuraBrics for constructing DronePorts, and supplying the cement for mortaring thousands of DronePorts—not just in Africa, but around the world. No mention, then, of who would pay for the eventual construction of these thousands of DronePorts, nor the millions of francs that would flow to LafargeHolcim. A small-scale publicity stunt, a generous funding of several small DronePorts, would kick off a worldwide investment in an entirely new transportation infrastructure in which LafargeHolcim would be, if not the only supplier of a crucial building material, certainly the preeminent supplier for a long time to come. Money makes the world go round.

Aravena’s entire Biennale, then, its emphasis on “natural” materials—the omnipresence of earthen brick and tile—its insistence on the collaboration among state and humanitarian actors, all lead to the quayside behind the Arsenale, to a Catalan vault through which a starchitect advances his brand and a global conglomerate advances its sales.

But the Droneport also offer a particularly insidious relationship among architecture, international development, and warfare. The Droneport project is spearheaded by The Norman Foster Foundation and Jonathan Ledgard, a former journalist who recently stepped down as director of Afrotech, an African development research center at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL).50 As the two men describe it, this drone network will eventually span a huge swathe of sub-Saharan Africa, though current efforts are concentrated on Ledgard’s so-called Redline project in Rwanda. The Redline will consist of a system of Droneports to transport medical and emergency supplies throughout the country of Rwanda, with the Rwandan government projected to pay one third of the cost of the initial network.51 With its small land area, densely-settled population, Western-educated and Anglophone elite, extensive network of fiber-optic internet cables, and post-genocide openness to foreign investment, Rwanda would seem like a natural starting point for the Droneport project.52 However, there is also the crucial matter of Rwanda’s relationship to its eastern neighbor, the Congo.53

A resource-poor yet densely populated country, Rwanda draws a large proportion of its budget from international aid while also drawing—both legally and illicitly—on the sale of Congolese minerals, including gold, diamonds, and metals such as coltan, an amalgam crucial for smart phones.54 In 2012-2013, the United States and the United Kingdom partially withheld aid to Rwanda as a rebuke for its involvement in armed conflict in the eastern Congo.55 Yet by 2015, funding had reached new heights, with the U.S. providing $247 million in aid to Rwanda, not including military aid, while the United Kingdom contributed roughly £70 million—this compared to Rwanda’s annual tax revenues of roughly $1.1 billion in 2015/2016.56 With roughly half of Rwanda’s national budget made up of aid from the U.S. and the U.K., one might consider the Rwandan government less as an enthusiastic backer of Norman Foster’s Droneport project and more as a conduit for British (and perhaps U.S.) investment in a drone network in Africa.57

That said, the Rwandan government’s strong control on its territory—including suppression of opposition parties, voter intimidation, reeducation camps that are compulsory for university matriculants, restrictions on freedom of speech, and centralized control of the economy under the guise of a private company held entirely by the current ruling party—means that the drone network will necessarily operate with considerable government oversight if not outright control.58 One glance at the proposed Droneport map reveals that the densest network of Redline routes is oriented along Rwanda’s border with the Congo, offering a multitude of opportunities for surveillance or even deployment of drones as weaponry in ongoing small-scale incursions into the Congo.59 From the very first, it was imagined that the drone project would soon expand into the Congo.60

Of course, even if this is not a priority—and, indeed, militarization would be a horrifying thought—for international development agencies backing the Droneport project, there is still the matter of profit motive. Alongside the Redline humanitarian drone network, Normal Foster’s foundation has also mooted the idea of a commercial Blueline “that would transport crucial larger payloads such as spare parts, electronics, and e-commerce, complementing and subsidising the Redline network.”61 Here one finds the holy grail for contemporary investment, the vast untapped mass of potential consumers in Africa, now hampered not only by economic misery but also by the inability for goods to reach market. In a philanthropic sense, drones with payloads of one hundred kilograms could allow agricultural producers to send goods to additional markets and potentially earn higher incomes.62 But more to the point for Western investors, drone-backed e-commerce could instantly reach hundreds of millions of consumers in sub-Saharan Africa.

In fact, an early report on the Droneport project foregrounded its commercial prospects: “Rwanda Plans Airport for E-Commerce Drones.”63 Moreover, even humanitarian drone deliveries would likely be imbricated within the health care tech industry. Already, blood and vaccines are being delivered across Rwanda by the for-profit California-based company Zipline, paid per delivery by the Rwandan government.64 With “$19 million in venture capital from investors including Sequoia Capital, Google Ventures, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, Yahoo co-founder Jerry Yang, and Subtraction Capital,” Zipline chose Rwanda as a test site for their drone deliveries based on a tip from the Redline’s Jonathan Ledgard. Now, the U.S. government is interested in copying the model for rural healthcare. As Killian Doherty’s excellent Thinkpiece in Architectural Review describes, the Droneport thus exemplifies the problem of “humanitarian architecture that is paradigmatically prone to being heavily narrated out of context, particularly the political context, and in a manner that distorts a view of the charged spaces of development as neutral.”65

Social (?) Architecture

Thus the Droneport offers the culmination of Aravena’s exhibition: in its materials (earthen tiles), in its forms (a tent-like shelter), and in that the humanitarian aspects of “social architecture” are necessarily implicated in ulterior motives on the part of stakeholders. At the risk of finding nefarious ends wherever an architectural project involves profit, it is necessary to understand how “the logic of real estate development under capitalism” underlies much of Aravena’s exhibition.66 Here we see why—despite the presence of so much government investment—this is not properly a biennale of “civic” or “public” architecture. The term “social” muddies the water just enough, introducing priorities that may conflict with the collective as administered by a state, or that project a transnational network of people—and, by extension, capital. It is this underlying thematic that differentiates Aravena’s exhibition from its predecessor, Andres Lepik’s 2010 exhibition Small Scale Big Change: New Architectures of Social Engagement, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.67

The market is omnipresent in this Architecture Biennale, with ownership at the heart of even the most “social” architectural projects. With a project for a French social housing apartment building, the architects’ language reiterated a normative (if not entirely puritanical) cycle of the nuclear family as “living together, marriage, children, and old age.”68 The presentation even had dollhouse-like models of domestic interiors and portraits of the inhabitants amidst the stuff of their new apartments, a vision of domestic nesting embodying a petit bourgeois aspiration to home ownership.69 At a Biennale panel discussion sponsored by LafargeHolcim, Aravena himself was even more explicit about the links between social architecture and private property (which may, in fact, be less relevant in the case of French social housing). Explaining his work in Chile, Aravena situated himself as part of a lineage reaching back to the Chilean government’s formalization of squatters’ plots in the 1970s, when “Operation Chalk,” enabled people to stake ownership over plots of land using chalk lines.70 The lines established “property structure and nothing more than that, just the geometry of who would own what, meaning this will be a street, this will be a private lot.”71 Or, as The New York Times Style Magazine explained of Aravena’s recent work in Constitución, “Residents of Villa Verde [in Constitución], who had next to nothing, gain equity.”72 Within Aravena’s vision of social architecture, there is always already private property to which we should aspire. This is not to say that humanitarian or social architectures should never involve the market, but that one must remain aware of the webs of capital and political motives that allow such architectures to exist.73

In this outsider biennale, finally, the relationship between architect and non-architect was left largely implicit. One notable exception can be found in comments by Sri Lankan architect Melinda Pathiraja during a panel discussion on sustainability and security.74 Pathiraja openly proclaimed the perhaps unfashionable view that experts are a necessary part of architecture, especially in the Global South. In Sri Lanka, Pathiraja asserted, less than a fraction of 1% of buildings were constructed under the auspices of architects, leading to a number of problems in safety and durability. One can quibble with the nature of the experts who could best address this perceived lack—wouldn’t engineers be just as useful as architects in preventing structural defects?—and find fault with the power relations implicit in this call for architects. However, Pathiraja’s point is well taken. We might simply rephrase it not as a call for experts, but as a call for expertise.

And here is where Aravena’s Biennale does a great service to the profession, in calling for a reevaluation of what constitutes expertise in the field of architecture. Rather than highlighting pre-industrial building techniques as a way to reinvigorate folkloric nationalisms, the exhibition fiercely defends the prowess of these techniques in their own right. These techniques are important not because they are native or traditional, but because they are functional.