[H]ypostatization is not acknowledgment. The continuing problem of how to acknowledge the literal character of the support – of what counts as that acknowledgment – has been at least as crucial to the development of modernist painting as the fact of its literalness, and that problem has been eliminated, not solved by the artists in question [the literalists]. Their pieces cannot be said to acknowledge literalness; they simply are literal.

—Michael Fried

As we acknowledge the importance of Michael Fried’s critical writings on this fiftieth anniversary of his seminal essay “Art and Objecthood,” it seems opportune to return to one of the fundamental concepts that he wields in his art criticism, that of acknowledgment. Although the term is used only rarely in “Art and Objecthood” itself (once, in footnote 16), it constitutes, through its regular presence in his other critical articles at the time, an essential element of the theoretical framework of the essay. And beyond the utility of reconstructing that framework for our understanding of the essay’s argument, the concept of acknowledgment as used by Fried merits attention in itself as one of his most important insights into the dynamics of the artwork.

As is appropriate for a concept such as acknowledgment, which is predicated upon the interaction of two entities, its role in Fried’s writings has a counterpart in its role in those of Stanley Cavell. In his introduction to Art and Objecthood, Fried speaks of the mutual interest that the two brought to the subject during their conversations that began in 1963.[1] For his part, Cavell speaks of their common focus on acknowledgment as “a continuing discovery of mutual profit.”[2] It is not my intention to enter into a discussion of the relations between the two theorists’ uses of the idea, which would be too long for this essay.[3] Rather I’ll remain with Fried’s analyses of modernist painting and sculpture in which a dynamic within the artwork is understood in terms of acknowledgment, in order to grasp the stakes of this concept when applied to art.

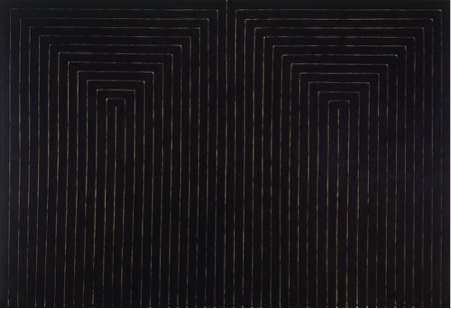

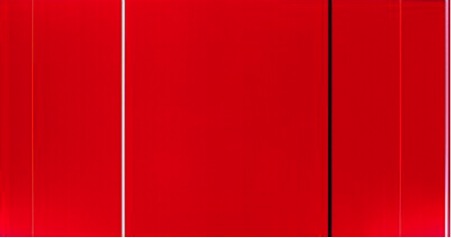

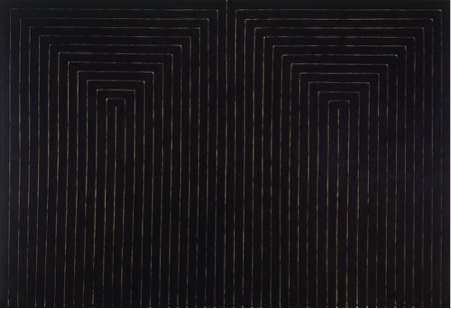

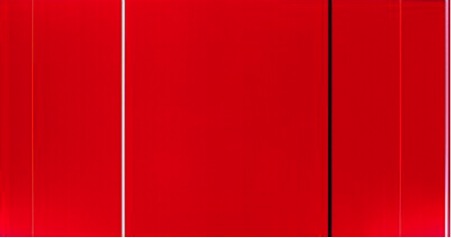

In his 1966 essay “Shape as Form: Frank Stella’s Irregular Polygons” and elsewhere in his early criticism, Fried describes the ways in which various elements of paintings and sculptures, such as a painting’s depicted shapes or a sculpture’s configuration, “acknowledge” the conditions or literal aspects of the medium, such as a painting’s flatness or the shape of its canvas, or a sculpture’s groundedness or placement on a table. For example, the stripes in Kenneth Noland’s diamond-shaped paintings [fig. 1] and in Frank Stella’s early stripe paintings [fig. 2] are said to acknowledge the shape of the support by paralleling it and thus in a way echoing and repeating it: “[Noland’s] four relatively broad bands of color run parallel to one or the other pair of sides, thereby acknowledging the shape of the support” (AO, 83); “Stella’s stripe paintings […] represent the most unequivocal and conflictless acknowledgment of literal shape in the history of modernism” (AO, 88). Likewise, the “zips” or thin vertical lines in Barnett Newman’s paintings [fig. 3] “amount to echoes within the painting of the two side framing edges; they relate primarily to those edges, and in so doing make explicit acknowledgment of the shape of the canvas” (AO, 233). Stella’s irregular polygons take this dynamic a step further by making the relationship between depicted shape and the literal shape of the support more intimate. In Moultonboro III [fig. 4] “the triangle itself comprises two elements – an eight-inch-wide light yellow band around its perimeter and the smaller triangle, in Day-Glo yellow, bounded by that band – both of which seem to be acknowledging, by repeating, the shape of the support” (AO, 89).[4] In these passages, Fried is describing the relation that obtains between the literal shape of the canvas and the shapes of the colored elements within; the colored lines echo, repeat and in a certain way refer to the shape of the support, and thus literal shape is acknowledged by depicted shape.

The analysis highlights the interdependence between these two elements in such a way that they enter into a non-arbitrary relation and are “made mutually responsive” (AO, 77), thereby creating a continuity between the interior and the exterior of the painting which overcomes the duality. This continuity may be seen clearly in the Effingham series [fig. 5], in which the colored bands in some places coincide with the edge of the painting, suggesting the frame and echoing the literal shape, and in others they are integrated into the depicted elements of the painting. The intertwining of the interior and exterior shapes in these paintings “radically recasts, we might say deconstructs, the very distinction between inside and outside” (AO, 63), as Fried wrote concerning Anthony Caro’s sculptures as seen from a Derridian standpoint. Caro’s sculptures likewise acknowledge the conditions of their physicality, whether situated on the ground without a plinth, or on a table. According to Fried, Caro wanted to create sculptures whose actual conditions of placement would not be arbitrary and extrinsic to the particular identity of the work, but would be integrated into, or acknowledged by, its “syntax” or the relations between its parts. His table sculptures [fig. 6] succeed in making their small size a non-contingent aspect of the work – they are not just large sculptures that have been shrunk – by incorporating the table edge into the sculpture’s configuration so that part of the sculpture necessarily hangs off the table, and thus it could not be placed on the ground. That is, their physical conditions and situation are acknowledged by their structure: “the distinction between tabling and grounding, because determined (or acknowledged) by the sculptures themselves instead of merely imposed upon them by their eventual placement, made itself felt as equivalent to a qualitative rather than a quantitative difference in scale” (AO, 190). And, “in the table sculptures, for example, Caro found himself compelled to acknowledge – to find or devise appropriate means for acknowledging – the generic conditions of their inescapable ‘framedness’” (AO, 32-33). It is possible to see this dynamic of acknowledgment at work also in Caro’s ground sculptures, such as Prairie [fig. 7], in which the two horizontal planes created by the row of poles and the sheet of metal echo or acknowledge the horizontality of the ground below, similarly to the way in which Stella’s or Noland’s stripes repeat the literal shape of the canvas. In general, Fried writes, Caro’s abandonment of the plinth participates in this desire to make sculptures that directly acknowledge the literal conditions of their situation: “he was the first to make sculptures which demanded to be placed on the ground, whose specific character would inevitably have been traduced if they were not so placed” (AO, 203). Thus the dynamic in which the work’s literal framing is acknowledged by its interior configuration results in a non-arbitrary relation between the two, overcoming the duality.

In Fried’s careful, detailed analyses of late modernist artworks, he describes various ways in which the literal (physical, material, situated, contingent) properties or conditions of a work are incorporated into it; thus contingency is integrated – and not abolished. His insight recalls Stéphane Mallarmé’s famous integration of chance into poetry in Un coup de dés (“A throw of the dice will never abolish chance”) and Le Livre, in which the contingent nature of the medium of language – and the impossibility ever to abolish this contingency – is acknowledged by the words, syntax and structure of the poems. This is a way of staving off the arbitrariness of the literal medium by integrating it (“absorbing” it, in one of Mallarmé’s formulations); the result is paradoxically a less arbitrary relation between the contingency of the medium and the particular elements of the poem than would have obtained without the direct acknowledgment of that contingency.[5] Thus we might understand Fried’s statement: “Caro on the one hand has frankly avowed the physicality of his sculpture and on the other has rendered that physicality unperspicuous” (AO, 183). Although Fried does use the terms contingency and arbitrariness, (“literal” and “contingent” are associated in his discussion of Caro, for example [AO, 205]), this terminology is not key in his analyses; however, I believe that he would not entirely disagree with their application here. Through the acknowledgment of its own contingency, the work is experienced as being less arbitrary, and (to use Fried’s terms) may thus inspire the beholder’s conviction.

This is the context in which we must understand Fried’s attack on literalism. It is important to recognize, when reading his critique of literalist sensibility in “Art and Objecthood,” that his view of literalness and contingency is not that these should be abolished from artworks (as though that could ever be possible! Mallarmé reminds us that it’s not), but that the literal and contingent properties of a work should be acknowledged and incorporated into it, creating an intimate and non-arbitrary relation between a work’s literal conditions and its configuration, between its situation and its syntax. The problem is not literalness, but what one does with it. The difficulty with minimalist works is that they cannot acknowledge their own literalness – not because there is nothing to acknowledge (they do have literal conditions and shape) but because there is nothing in them to do the acknowledging. They have no parts, no configuration, no syntax capable of entering into relation with their literalness; they are “hollow” (AO, 151). As unitary works, they “hypostatize” literalness as such, simply manifesting their literal conditions, and thus remain arbitrary. The trouble is not literalness itself, then, but literalness in itself. This is how we should understand the phrase cited in my epigraph, “hypostatization is not acknowledgment,” which is key to understanding “Art and Objecthood” and might ring as somewhat cryptic if this background isn’t clear. “[Literalist] pieces cannot be said to acknowledge literalness; they simply are literal” (AO, 88). In Stella’s irregular polygons, on the other hand, literalness “is no longer experienced as the exclusive property of the support. Rather, it is suffused more generally and, as it were, more deeply throughout them” (AO, 92-93). As Mallarmé would say, it is “absorbed,” thus overcoming the distinction between outside and inside. Literalness is not antithetical to the modernist artworks that Fried advocates, which do not abolish but rather acknowledge their literalness and contingency. This is what is meant when Fried states that shape “must be pictorial, not, or not merely, literal” (AO, 151, emphasis added). Objecthood, then, in Fried’s terminology, is not synonymous with literalness, but would be the result of the simple hypostatization or manifestation of literalness, rather than its acknowledgment.

Fried insists on the historically contingent nature of the literal conditions and properties that a given artwork may be said to acknowledge at any given time. That is, the object of acknowledgment is proper to every work and not generalizable to any ahistorical, essential qualities of a medium, which do not exist. (See Fried’s critique of Clement Greenberg’s essentialism [AO, 33-40].) Furthermore, the process of acknowledgment, the dynamic of relations that may be created between the inside and outside of a work, is also proper to every work, artist and period. “It is a historical question what in a given instance counted as acknowledging one or another property or condition of that medium, just as it is a historical question how most accurately to describe the property or condition that the acknowledgment was of. (The determining properties or conditions of a medium in a given instance might be virtually anything; at any rate, they can’t simply be identified with materiality as such.)”[6] That which is acknowledged, as well as that which a beholder may perceive as a dynamic of acknowledgment between the configurations, images, “syntax” or other elements and their literal conditions – ultimately, that which compels a beholder’s conviction in this dynamic – is historically contingent and changing.[7]

Fried’s focus on historicizing the properties of an artwork and the dynamic of acknowledgment participates in his critique of Greenberg, for whom the development of modernism consisted in the progressive manifestation of a medium’s “irreducible essence” – which, Fried argues, resulted in literalism.[8] According to Fried, the literalists’ hypostatization of literalness is simply the endpoint of Greenberg’s modernist reduction of a medium to its essential and literal qualities. It is important to note that despite a certain similarity of vocabulary, the process Greenberg describes in “Modernist Painting” and elsewhere is quite different from the dynamic of acknowledgment that Fried analyses.[9] For Greenberg, art’s movement of self-declaration is one of gradual, “radical simplification” of the medium; a modernist work explicitly indicates its properties “in order to exhibit them more clearly as norms. By being exhibited, they are tested for their indispensability.”[10] If not indispensable, they will be shed. The evolution is toward purification and ever greater explicitness of the medium’s “essence.” Whereas Greenberg describes a sort of hollowing out of the insides of painting as it becomes all surface, Fried emphasizes the intimate relations created between the interior configuration of a work and its material conditions, as its literal properties are acknowledged by its depicted elements.

In his later writings, Fried associates the idea of explicitness with Greenberg’s version of modernist self-criticism and the literalism it produced, and attempts to keep it separate from the concept of acknowledgment. In a footnote to his introduction to Art and Objecthood Fried laments that in his early critical writings he often used the two together.[11] However, the concepts are indeed difficult to separate, and ultimately he need not worry. The problem with Greenberg’s theory was not the concept of explicitness, but his idea of a progressive purification or reduction to mere explicitness. (Just as the problem with literalness is not the fact of literalness, as I argued above, but mere literalness, nothing but literalness.) It would be impossible entirely to separate the concepts of acknowledgment and explicitness; acknowledgment implies the act of bringing something to light, expressing something, rendering something clear either in deed, words or conscious awareness. In art, the relations between depicted elements and physical conditions become evident to a beholder through the dynamic we have been calling acknowledgment. As Cavell writes, “Acknowledgment ‘goes beyond’ knowledge, […] in the call upon me to express the knowledge at its core, to recognize what I know, to do something in the light of it, apart from which this knowledge remains without expression, hence perhaps without possession.”[12] And elsewhere, acknowledgment “goes beyond [knowledge] in its requirement that I do something or reveal something on the basis of that knowledge.”[13] The act of acknowledgment inevitably involves something passing from a less to a more explicit state, even if that takes place only within one’s own consciousness. Cavell, again: “[Acknowledgment] is like something hidden in consciousness declaring itself. The mode is revelation. I follow Michael Fried in speaking of this fact of modernist painting as an acknowledging of its conditions.”[14] While acknowledgment always comprises (can never abolish) some kind of explicitness, neither can it be identified with simple exhibition, mere explicitness. As with literalness, what counts with explicitness is what one does with it; literalism does nothing but explicitly exhibit its partless singularity, while in modernism a work’s configuration explicitly integrates – acknowledges – its conditions. Thus we may prize the concept of explicitness away from Greenberg’s use of it.

We should distinguish the concept of acknowledgment from that of self-critique, as theorized by Greenberg, as well as from the other “self-” prefixed terms he uses such as self-declaration, self-definition, self-confession. This focus on the self-activity of a medium or an artwork foreshadows minimalism’s wholeness or unitary character, criticized by Fried in “Art and Objecthood.” The problem, again, is that this self-manifestation is conceived as not having parts or internal relations; there is only one element (or, for Greenberg, extraneous elements will eventually be discarded). I began by mentioning the fact that acknowledgment is predicated upon the interaction of two entities (x acknowledges y), and have gone on to show how in Fried’s analysis of art this process leads to a mutual responsiveness and a continuity between the two which overcome the duality. Ultimately, in a sense, both minimalism and modernism sought non-dualism, though through radically different routes – minimalism by manifesting simple, literal singularity and wholeness, modernism by entering into a dynamic of co-implication, intertwining and acknowledgment. Minimalism pretends to arrive at non-dualism by simply eliminating duality and positing unity by fiat; modernism by the much more difficult route of acknowledging alterity and overcoming duality through creating non-arbitrary relations.

Acknowledgment is an anthropomorphic concept when applied to art, as it is normally a human act. It implies notions of consciousness, communication and sincerity. Fried’s criticism of the anthropomorphism of literalism in “Art and Objecthood” is not aimed at anthropomorphism as such, but at the insincere and theatrical manifestations of it he saw in literalist art (“what is wrong with literalist work is not that it is anthropomorphic but that the meaning and, equally, the hiddenness of its anthropomorphism are incurably theatrical” [AO, 157]). What would an anthropomorphic artwork be like that is not hollow or just a theatrical surface, but one that is human and sincere?[15] One answer is a work that explicitly acknowledges its own conditions, framedness, contingency. And to follow out the analogy, what would it mean for a human to acknowledge her or his own literal conditions, situation, materiality, framedness (in time…), internal alterity? Acknowledging one’s own contingency is not a simple matter (try it). Nor is it simple to create artworks that invite beholders to ask such questions, and to search themselves for answers. These are the stakes of modernist acknowledgment.

[1] Michael Fried, “An Introduction to My Art Criticism,” in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 37 (henceforth AO).

[2] Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 239. He writes, “The concept of acknowledgment first showed its significance to me in thinking about our knowledge of other minds, in such a way as to show (what I took to be) modern philosophy neither defeating nor defeated by skepticism. It showed its significance to Michael Fried in characterizing the medium or enterprise of the art of painting” (239).

[3] For Cavell’s discussions of painting and film in terms of acknowledgment, see especially The World Viewed, 108-26; on the role of acknowledgment in his arguments on skepticism, see Must We Mean What We Say? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 238-66, and The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), 329-496.

[4] The term “acknowledgment” was intended to replace Fried’s earlier conception of “deductive structure,” a more deterministic or mechanistic formulation, referring to the way in which the stripes in Stella’s early stripe paintings, for example, echo or are derived from the literal shape of the painting. (See AO, 23-4.) A lingering association of the idea of acknowledgment with this form of simple (parallel) repetition seems to explain the statement in “Shape as Form” that Stella’s irregular polygons do not acknowledge literal shape (AO, 94); however, a few pages earlier Moultonboro III is analyzed in terms of acknowledgment.

[5] Stéphane Mallarmé, “Igitur,” in Oeuvres Complètes, 2 vols., ed. Bertrand Marchal (Paris: Gallimard, 1998-2001), 1:478.

[6] Michael Fried, Courbet’s Realism (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1990), 285.

[7] For example, he sees in Manet’s paintings of the 1860s an acknowledgment of “the primordial convention that paintings are made to be beheld,” Manet’s Modernism, or, The Face of Painting in the 1860s (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 405; see also Courbet’s Realism, 286.

[8] Clement Greenberg, “After Abstract Expressionism,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism, Vol. 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957-1969 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 131. See also “Sculpture in our Time” and “Modernist Painting” in the same volume, as well as Fried’s discussion in AO, 33-40 and 66. “Literal” is a term used often by Greenberg in his criticism (for example, in “Sculpture in our Time”) although not with the consistent philosophical charge used by Fried.

[9] It is possible that in the concept of acknowledgment we may witness Fried prizing the term away from Greenberg’s theorizing, with Cavell’s help, thus overcoming the influence of the elder critic.

[10] Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” 89.

[11] “Unfortunately, I continued to deploy the concept of explicitness in connection with that of acknowledgment in ‘Shape as Form’ and subsequent essays, which I think was a mistake: part of the point of stressing acknowledgment in those contexts was to avoid the pitfalls of the idea of making explicit, and I wish I had kept the two terms rigorously separate. And yet the fact that I did not, indeed that the phrases ‘explicit acknowledgment’ and ‘explicitly acknowledge’ came so readily to hand, suggests that the distinction in question was (and, I think, still is) conceptually insecure. I’m not sure what to do about this other than to call attention to the problem” (AO, 65). See also Courbet’s Realism, 285.

[12] Cavell, The Claim of Reason, 428; cited by Michael Fried, Courbet’s Realism, 364.

[13] Cavell, Must We Mean What We Say? 257.

[14] Cavell, The World Viewed, 109.

[15] See Lisa Siraganian, “Art and Surrogate Personhood,” nonsite.org 21 (July 2017): n.p.; https://nonsite.org/article/art-and-surrogate-personhood-2

[H]ypostatization is not acknowledgment. The continuing problem of how to acknowledge the literal character of the support – of what counts as that acknowledgment – has been at least as crucial to the development of modernist painting as the fact of its literalness, and that problem has been eliminated, not solved by the artists in question [the literalists]. Their pieces cannot be said to acknowledge literalness; they simply are literal.

—Michael Fried

As we acknowledge the importance of Michael Fried’s critical writings on this fiftieth anniversary of his seminal essay “Art and Objecthood,” it seems opportune to return to one of the fundamental concepts that he wields in his art criticism, that of acknowledgment. Although the term is used only rarely in “Art and Objecthood” itself (once, in footnote 16), it constitutes, through its regular presence in his other critical articles at the time, an essential element of the theoretical framework of the essay. And beyond the utility of reconstructing that framework for our understanding of the essay’s argument, the concept of acknowledgment as used by Fried merits attention in itself as one of his most important insights into the dynamics of the artwork.

As is appropriate for a concept such as acknowledgment, which is predicated upon the interaction of two entities, its role in Fried’s writings has a counterpart in its role in those of Stanley Cavell. In his introduction to Art and Objecthood, Fried speaks of the mutual interest that the two brought to the subject during their conversations that began in 1963.[1] For his part, Cavell speaks of their common focus on acknowledgment as “a continuing discovery of mutual profit.”[2] It is not my intention to enter into a discussion of the relations between the two theorists’ uses of the idea, which would be too long for this essay.[3] Rather I’ll remain with Fried’s analyses of modernist painting and sculpture in which a dynamic within the artwork is understood in terms of acknowledgment, in order to grasp the stakes of this concept when applied to art.

In his 1966 essay “Shape as Form: Frank Stella’s Irregular Polygons” and elsewhere in his early criticism, Fried describes the ways in which various elements of paintings and sculptures, such as a painting’s depicted shapes or a sculpture’s configuration, “acknowledge” the conditions or literal aspects of the medium, such as a painting’s flatness or the shape of its canvas, or a sculpture’s groundedness or placement on a table. For example, the stripes in Kenneth Noland’s diamond-shaped paintings [fig. 1] and in Frank Stella’s early stripe paintings [fig. 2] are said to acknowledge the shape of the support by paralleling it and thus in a way echoing and repeating it: “[Noland’s] four relatively broad bands of color run parallel to one or the other pair of sides, thereby acknowledging the shape of the support” (AO, 83); “Stella’s stripe paintings […] represent the most unequivocal and conflictless acknowledgment of literal shape in the history of modernism” (AO, 88). Likewise, the “zips” or thin vertical lines in Barnett Newman’s paintings [fig. 3] “amount to echoes within the painting of the two side framing edges; they relate primarily to those edges, and in so doing make explicit acknowledgment of the shape of the canvas” (AO, 233). Stella’s irregular polygons take this dynamic a step further by making the relationship between depicted shape and the literal shape of the support more intimate. In Moultonboro III [fig. 4] “the triangle itself comprises two elements – an eight-inch-wide light yellow band around its perimeter and the smaller triangle, in Day-Glo yellow, bounded by that band – both of which seem to be acknowledging, by repeating, the shape of the support” (AO, 89).[4] In these passages, Fried is describing the relation that obtains between the literal shape of the canvas and the shapes of the colored elements within; the colored lines echo, repeat and in a certain way refer to the shape of the support, and thus literal shape is acknowledged by depicted shape.

The analysis highlights the interdependence between these two elements in such a way that they enter into a non-arbitrary relation and are “made mutually responsive” (AO, 77), thereby creating a continuity between the interior and the exterior of the painting which overcomes the duality. This continuity may be seen clearly in the Effingham series [fig. 5], in which the colored bands in some places coincide with the edge of the painting, suggesting the frame and echoing the literal shape, and in others they are integrated into the depicted elements of the painting. The intertwining of the interior and exterior shapes in these paintings “radically recasts, we might say deconstructs, the very distinction between inside and outside” (AO, 63), as Fried wrote concerning Anthony Caro’s sculptures as seen from a Derridian standpoint. Caro’s sculptures likewise acknowledge the conditions of their physicality, whether situated on the ground without a plinth, or on a table. According to Fried, Caro wanted to create sculptures whose actual conditions of placement would not be arbitrary and extrinsic to the particular identity of the work, but would be integrated into, or acknowledged by, its “syntax” or the relations between its parts. His table sculptures [fig. 6] succeed in making their small size a non-contingent aspect of the work – they are not just large sculptures that have been shrunk – by incorporating the table edge into the sculpture’s configuration so that part of the sculpture necessarily hangs off the table, and thus it could not be placed on the ground. That is, their physical conditions and situation are acknowledged by their structure: “the distinction between tabling and grounding, because determined (or acknowledged) by the sculptures themselves instead of merely imposed upon them by their eventual placement, made itself felt as equivalent to a qualitative rather than a quantitative difference in scale” (AO, 190). And, “in the table sculptures, for example, Caro found himself compelled to acknowledge – to find or devise appropriate means for acknowledging – the generic conditions of their inescapable ‘framedness’” (AO, 32-33). It is possible to see this dynamic of acknowledgment at work also in Caro’s ground sculptures, such as Prairie [fig. 7], in which the two horizontal planes created by the row of poles and the sheet of metal echo or acknowledge the horizontality of the ground below, similarly to the way in which Stella’s or Noland’s stripes repeat the literal shape of the canvas. In general, Fried writes, Caro’s abandonment of the plinth participates in this desire to make sculptures that directly acknowledge the literal conditions of their situation: “he was the first to make sculptures which demanded to be placed on the ground, whose specific character would inevitably have been traduced if they were not so placed” (AO, 203). Thus the dynamic in which the work’s literal framing is acknowledged by its interior configuration results in a non-arbitrary relation between the two, overcoming the duality.

In Fried’s careful, detailed analyses of late modernist artworks, he describes various ways in which the literal (physical, material, situated, contingent) properties or conditions of a work are incorporated into it; thus contingency is integrated – and not abolished. His insight recalls Stéphane Mallarmé’s famous integration of chance into poetry in Un coup de dés (“A throw of the dice will never abolish chance”) and Le Livre, in which the contingent nature of the medium of language – and the impossibility ever to abolish this contingency – is acknowledged by the words, syntax and structure of the poems. This is a way of staving off the arbitrariness of the literal medium by integrating it (“absorbing” it, in one of Mallarmé’s formulations); the result is paradoxically a less arbitrary relation between the contingency of the medium and the particular elements of the poem than would have obtained without the direct acknowledgment of that contingency.[5] Thus we might understand Fried’s statement: “Caro on the one hand has frankly avowed the physicality of his sculpture and on the other has rendered that physicality unperspicuous” (AO, 183). Although Fried does use the terms contingency and arbitrariness, (“literal” and “contingent” are associated in his discussion of Caro, for example [AO, 205]), this terminology is not key in his analyses; however, I believe that he would not entirely disagree with their application here. Through the acknowledgment of its own contingency, the work is experienced as being less arbitrary, and (to use Fried’s terms) may thus inspire the beholder’s conviction.

This is the context in which we must understand Fried’s attack on literalism. It is important to recognize, when reading his critique of literalist sensibility in “Art and Objecthood,” that his view of literalness and contingency is not that these should be abolished from artworks (as though that could ever be possible! Mallarmé reminds us that it’s not), but that the literal and contingent properties of a work should be acknowledged and incorporated into it, creating an intimate and non-arbitrary relation between a work’s literal conditions and its configuration, between its situation and its syntax. The problem is not literalness, but what one does with it. The difficulty with minimalist works is that they cannot acknowledge their own literalness – not because there is nothing to acknowledge (they do have literal conditions and shape) but because there is nothing in them to do the acknowledging. They have no parts, no configuration, no syntax capable of entering into relation with their literalness; they are “hollow” (AO, 151). As unitary works, they “hypostatize” literalness as such, simply manifesting their literal conditions, and thus remain arbitrary. The trouble is not literalness itself, then, but literalness in itself. This is how we should understand the phrase cited in my epigraph, “hypostatization is not acknowledgment,” which is key to understanding “Art and Objecthood” and might ring as somewhat cryptic if this background isn’t clear. “[Literalist] pieces cannot be said to acknowledge literalness; they simply are literal” (AO, 88). In Stella’s irregular polygons, on the other hand, literalness “is no longer experienced as the exclusive property of the support. Rather, it is suffused more generally and, as it were, more deeply throughout them” (AO, 92-93). As Mallarmé would say, it is “absorbed,” thus overcoming the distinction between outside and inside. Literalness is not antithetical to the modernist artworks that Fried advocates, which do not abolish but rather acknowledge their literalness and contingency. This is what is meant when Fried states that shape “must be pictorial, not, or not merely, literal” (AO, 151, emphasis added). Objecthood, then, in Fried’s terminology, is not synonymous with literalness, but would be the result of the simple hypostatization or manifestation of literalness, rather than its acknowledgment.

Fried insists on the historically contingent nature of the literal conditions and properties that a given artwork may be said to acknowledge at any given time. That is, the object of acknowledgment is proper to every work and not generalizable to any ahistorical, essential qualities of a medium, which do not exist. (See Fried’s critique of Clement Greenberg’s essentialism [AO, 33-40].) Furthermore, the process of acknowledgment, the dynamic of relations that may be created between the inside and outside of a work, is also proper to every work, artist and period. “It is a historical question what in a given instance counted as acknowledging one or another property or condition of that medium, just as it is a historical question how most accurately to describe the property or condition that the acknowledgment was of. (The determining properties or conditions of a medium in a given instance might be virtually anything; at any rate, they can’t simply be identified with materiality as such.)”[6] That which is acknowledged, as well as that which a beholder may perceive as a dynamic of acknowledgment between the configurations, images, “syntax” or other elements and their literal conditions – ultimately, that which compels a beholder’s conviction in this dynamic – is historically contingent and changing.[7]

Fried’s focus on historicizing the properties of an artwork and the dynamic of acknowledgment participates in his critique of Greenberg, for whom the development of modernism consisted in the progressive manifestation of a medium’s “irreducible essence” – which, Fried argues, resulted in literalism.[8] According to Fried, the literalists’ hypostatization of literalness is simply the endpoint of Greenberg’s modernist reduction of a medium to its essential and literal qualities. It is important to note that despite a certain similarity of vocabulary, the process Greenberg describes in “Modernist Painting” and elsewhere is quite different from the dynamic of acknowledgment that Fried analyses.[9] For Greenberg, art’s movement of self-declaration is one of gradual, “radical simplification” of the medium; a modernist work explicitly indicates its properties “in order to exhibit them more clearly as norms. By being exhibited, they are tested for their indispensability.”[10] If not indispensable, they will be shed. The evolution is toward purification and ever greater explicitness of the medium’s “essence.” Whereas Greenberg describes a sort of hollowing out of the insides of painting as it becomes all surface, Fried emphasizes the intimate relations created between the interior configuration of a work and its material conditions, as its literal properties are acknowledged by its depicted elements.

In his later writings, Fried associates the idea of explicitness with Greenberg’s version of modernist self-criticism and the literalism it produced, and attempts to keep it separate from the concept of acknowledgment. In a footnote to his introduction to Art and Objecthood Fried laments that in his early critical writings he often used the two together.[11] However, the concepts are indeed difficult to separate, and ultimately he need not worry. The problem with Greenberg’s theory was not the concept of explicitness, but his idea of a progressive purification or reduction to mere explicitness. (Just as the problem with literalness is not the fact of literalness, as I argued above, but mere literalness, nothing but literalness.) It would be impossible entirely to separate the concepts of acknowledgment and explicitness; acknowledgment implies the act of bringing something to light, expressing something, rendering something clear either in deed, words or conscious awareness. In art, the relations between depicted elements and physical conditions become evident to a beholder through the dynamic we have been calling acknowledgment. As Cavell writes, “Acknowledgment ‘goes beyond’ knowledge, […] in the call upon me to express the knowledge at its core, to recognize what I know, to do something in the light of it, apart from which this knowledge remains without expression, hence perhaps without possession.”[12] And elsewhere, acknowledgment “goes beyond [knowledge] in its requirement that I do something or reveal something on the basis of that knowledge.”[13] The act of acknowledgment inevitably involves something passing from a less to a more explicit state, even if that takes place only within one’s own consciousness. Cavell, again: “[Acknowledgment] is like something hidden in consciousness declaring itself. The mode is revelation. I follow Michael Fried in speaking of this fact of modernist painting as an acknowledging of its conditions.”[14] While acknowledgment always comprises (can never abolish) some kind of explicitness, neither can it be identified with simple exhibition, mere explicitness. As with literalness, what counts with explicitness is what one does with it; literalism does nothing but explicitly exhibit its partless singularity, while in modernism a work’s configuration explicitly integrates – acknowledges – its conditions. Thus we may prize the concept of explicitness away from Greenberg’s use of it.

We should distinguish the concept of acknowledgment from that of self-critique, as theorized by Greenberg, as well as from the other “self-” prefixed terms he uses such as self-declaration, self-definition, self-confession. This focus on the self-activity of a medium or an artwork foreshadows minimalism’s wholeness or unitary character, criticized by Fried in “Art and Objecthood.” The problem, again, is that this self-manifestation is conceived as not having parts or internal relations; there is only one element (or, for Greenberg, extraneous elements will eventually be discarded). I began by mentioning the fact that acknowledgment is predicated upon the interaction of two entities (x acknowledges y), and have gone on to show how in Fried’s analysis of art this process leads to a mutual responsiveness and a continuity between the two which overcome the duality. Ultimately, in a sense, both minimalism and modernism sought non-dualism, though through radically different routes – minimalism by manifesting simple, literal singularity and wholeness, modernism by entering into a dynamic of co-implication, intertwining and acknowledgment. Minimalism pretends to arrive at non-dualism by simply eliminating duality and positing unity by fiat; modernism by the much more difficult route of acknowledging alterity and overcoming duality through creating non-arbitrary relations.

Acknowledgment is an anthropomorphic concept when applied to art, as it is normally a human act. It implies notions of consciousness, communication and sincerity. Fried’s criticism of the anthropomorphism of literalism in “Art and Objecthood” is not aimed at anthropomorphism as such, but at the insincere and theatrical manifestations of it he saw in literalist art (“what is wrong with literalist work is not that it is anthropomorphic but that the meaning and, equally, the hiddenness of its anthropomorphism are incurably theatrical” [AO, 157]). What would an anthropomorphic artwork be like that is not hollow or just a theatrical surface, but one that is human and sincere?[15] One answer is a work that explicitly acknowledges its own conditions, framedness, contingency. And to follow out the analogy, what would it mean for a human to acknowledge her or his own literal conditions, situation, materiality, framedness (in time…), internal alterity? Acknowledging one’s own contingency is not a simple matter (try it). Nor is it simple to create artworks that invite beholders to ask such questions, and to search themselves for answers. These are the stakes of modernist acknowledgment.

[1] Michael Fried, “An Introduction to My Art Criticism,” in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 37 (henceforth AO).

[2] Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 239. He writes, “The concept of acknowledgment first showed its significance to me in thinking about our knowledge of other minds, in such a way as to show (what I took to be) modern philosophy neither defeating nor defeated by skepticism. It showed its significance to Michael Fried in characterizing the medium or enterprise of the art of painting” (239).

[3] For Cavell’s discussions of painting and film in terms of acknowledgment, see especially The World Viewed, 108-26; on the role of acknowledgment in his arguments on skepticism, see Must We Mean What We Say? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 238-66, and The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), 329-496.

[4] The term “acknowledgment” was intended to replace Fried’s earlier conception of “deductive structure,” a more deterministic or mechanistic formulation, referring to the way in which the stripes in Stella’s early stripe paintings, for example, echo or are derived from the literal shape of the painting. (See AO, 23-4.) A lingering association of the idea of acknowledgment with this form of simple (parallel) repetition seems to explain the statement in “Shape as Form” that Stella’s irregular polygons do not acknowledge literal shape (AO, 94); however, a few pages earlier Moultonboro III is analyzed in terms of acknowledgment.

[5] Stéphane Mallarmé, “Igitur,” in Oeuvres Complètes, 2 vols., ed. Bertrand Marchal (Paris: Gallimard, 1998-2001), 1:478.

[6] Michael Fried, Courbet’s Realism (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1990), 285.

[7] For example, he sees in Manet’s paintings of the 1860s an acknowledgment of “the primordial convention that paintings are made to be beheld,” Manet’s Modernism, or, The Face of Painting in the 1860s (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 405; see also Courbet’s Realism, 286.

[8] Clement Greenberg, “After Abstract Expressionism,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism, Vol. 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957-1969 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 131. See also “Sculpture in our Time” and “Modernist Painting” in the same volume, as well as Fried’s discussion in AO, 33-40 and 66. “Literal” is a term used often by Greenberg in his criticism (for example, in “Sculpture in our Time”) although not with the consistent philosophical charge used by Fried.

[9] It is possible that in the concept of acknowledgment we may witness Fried prizing the term away from Greenberg’s theorizing, with Cavell’s help, thus overcoming the influence of the elder critic.

[10] Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” 89.

[11] “Unfortunately, I continued to deploy the concept of explicitness in connection with that of acknowledgment in ‘Shape as Form’ and subsequent essays, which I think was a mistake: part of the point of stressing acknowledgment in those contexts was to avoid the pitfalls of the idea of making explicit, and I wish I had kept the two terms rigorously separate. And yet the fact that I did not, indeed that the phrases ‘explicit acknowledgment’ and ‘explicitly acknowledge’ came so readily to hand, suggests that the distinction in question was (and, I think, still is) conceptually insecure. I’m not sure what to do about this other than to call attention to the problem” (AO, 65). See also Courbet’s Realism, 285.

[12] Cavell, The Claim of Reason, 428; cited by Michael Fried, Courbet’s Realism, 364.

[13] Cavell, Must We Mean What We Say? 257.

[14] Cavell, The World Viewed, 109.

[15] See Lisa Siraganian, “Art and Surrogate Personhood,” nonsite.org 21 (July 2017): n.p.; https://nonsite.org/article/art-and-surrogate-personhood-2