Once omnipresent in Western art, where it served to underline both the otherworldly character of religious subjects and the material wealth of artworks’ sponsors, gold almost entirely disappeared from painted panels and canvases by the sixteenth century. Outlined in convincing detail in Michael Baxandall’s classic Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (1972), the historical context and contours of this transition are today well-established.1 More than simply old-fashioned, the presence of gold and other precious, typically lustrous, materials came to be seen by makers and theorists of art as undermining the very definition of painting and what it meant, more generally, to be an artist.2

Laying the foundations for what would become a customary distinction between aesthetic and economic value, Leon Battista Alberti, writing in the fifteenth century, sharply distinguished the pleasures of art from those of property. Unlike a piece of expensive jewelry or the miser’s gold coin, the ideal work of art transfixed viewers through its skillful, illusionistic deployment of line and color. “[T]here are those who utilize gold in a disproportionate way because they think that gold lends a certain majesty to the historia. I do not approve of them at all. Indeed, if I would like to paint Virgil’s Dido with a golden quiver, [who] kept [her] hair in a knot with a golden clasp, [for] whom a golden band girded [her] dress, and who rode with golden reins, and, in general, all things shone because of the gold, I [would] strive, nevertheless, to imitate by means of colors rather than means of gold that abundance of golden rays that strikes observers’ eyes from every part,” Alberti contended.3 In fact, theorists and collectors would increasingly come to see the ability to imitate precious metals—gold especially—using ordinary, non-metallic pigments as a measure of an artist’s skill. Persistence in using gold and other expensive, eye-catching materials became, meanwhile, the mark of painters seeking to cover up deficiencies in their design or, worse, willingly abandoning what they knew to be true and good to cater to the untutored tastes of patrons.4

These ideas had a powerful, long-lasting influence on the making and theorization of art in the West, including, not least, in nineteenth-century Britain. George Field, the famed color theorist and manufacturer of artists’ pigments, was adamant, for example, that metallic luster had no place whatsoever in painting. As he observed in Chromatography (1835), “had there been blue and red metals equal in beauty to the yellow of gold, their brilliancy would probably have driven other coloured pigments from the field of early art; but the modesty of nature has wisely denied such meretricious beauty to the painter; metallic tones being as harsh and unsavory to chaste sense in painting as they are in music.”5 Medieval illuminators’ use of gold was likely a response to the scarcity of high-quality yellow pigments, he reasoned.6

Most nineteenth-century painting manuals skipped the topic entirely, considering it unnecessary to go over what was obviously a settled matter. “Those who use gold or silver leaf on their works or who have inserted precious stones or the like in them, if it be true that this has been done, have no less departed from the definition [of painting], which requires the imitation of natural objects, not the use of the objects themselves,” noted François-Xavier de Burtin in one of the rare nineteenth-century painting manuals to explicitly address the issue.7 It is hard to believe that the author’s stance surprised very many readers.

Confounding this elementary distinction between the thing itself and its representation with their reflective golden highlights, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1848–49) and Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation) (1849–50) offer one of the earliest, and least studied, avant-gardist challenges to established Albertian definitions of painting (figs. 1 and 2).8 Rossetti continued to employ gold in his paintings throughout his career, becoming progressively bolder in his challenge of the “definition of painting” as time went on. Completed in 1874, Sancta Lilias represents the artist’s most daring experiment with gilding (fig. 3). Confronted with the astonishing appearance of these artworks, not to mention their rejection of one of the most well-established and arguably consequential rules of artmaking, one is inevitably led to wonder: When gold does make its meretricious, kitschy reappearance, more specifically in Victorian avant-garde art, what meanings did it carry? Where do Rossetti’s The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, Ecce Ancilla Domini!, and later Sancta Lilas fit within the Victorian visual economy of light and luster? And finally, what function did gold play in Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic artists’ efforts to redefine art—not just its look or style, but the functions art was made to assume in modern British society, the meanings it was entrusted to carry, and the standards by which its value was measured?

The article that follows shows how, in the context of contemporaneous debates surrounding the purpose and status of the arts in Britain, the world’s most advanced capitalist economy, Rossetti’s leveraging of gold and related visual idioms closely associated with economic value, such as shine, inevitably took on the character of a bold, calculated move. By simultaneously mobilizing and resisting established understandings of the metal’s economic value and explicit connections with money, the artist’s gilded creations took part in a broader conversation taking place among nineteenth-century political economists, politicians, social commentators, and ordinary citizens about the nature and source of economic value and the ways markets were progressively becoming, in Britain especially, the dominant organizing principle of society.

Compared to art critic John Ruskin, who in the late 1850s almost entirely refocused his attention on matters of political economy, Rossetti’s dedication to broad social and political reform comes off as both sporadic and superficial. Scholarship on the artist’s dealings with patrons and the art market paints the picture of an individual who, in his later career especially, had largely reconciled himself with the commodified status of art. Drawing inspiration from contemporary art history, where scholars have been much more willing to regard artists as sources of economic knowledge, the analysis I present here complicates this narrative by highlighting aspects of Rossetti’s use of gilding that foreshadowed and overlapped with Ruskin’s controversial efforts to reimagine key tenets of political economists’ “science of values.”9 More than simply challenging established definitions of painting and aesthetic value, Rossetti’s conspicuous uses of and references to gold offered an alternative to the era’s dominant understandings of wealth and worth.

The argument developed in this article thus revises established understandings of Rossetti’s life and work, where the use of gold, if mentioned at all, serves mostly to confirm what we already know about the artist’s tastes, techniques, and aspirations. Foregrounding the Pre-Raphaelite pioneer’s interest in reviving earlier traditions of artmaking, these interpretations hardly exhaust the meaning of what became a standing aesthetic practice for the artist. In the age of the gold standard and gold rush, the return to gilding carried not only historical but also distinctly modern meanings. Similarly, scholarship centered on Rossetti’s later works, the blurring of the boundary between the fine and decorative arts, and what some have described as the increasingly decorative character of the artist’s paintings, does not fully account for the emphatically economic and monetary associations of gold in this period.10

The artist’s harnessing of the material basis and chief conceptual idiom of economic value in Victorian society cannot be pure happenstance. Nor could it have gone unnoticed by viewers in the context of the great public debates surrounding the gold standard and the monetary effects of the Californian and Australian gold discoveries. That Ruskin failed to draw attention to Rossetti’s and other Pre-Raphaelites’ use of gold is thus especially noteworthy. Focused on artists’ painstaking reproduction of what he called “actual facts” and the spiritual value of honest labor, Ruskin, I suggest, struggled to recognize other ways artists had of creating meaning. The economic value of gold presented in his view a fundamental challenge both to art and to society. For Rossetti, by contrast, gold’s economic and monetary associations were something to be harnessed, wielded as a weapon, or presented as an offering. His reinterpretation of gold and gilding served, therefore, a patently modern, even modernist, agenda: not the pursuit of novelty or Greenbergian “flatness” but the purposeful interrogation of established standards of value.11

Gilding the Lily: Early Rossetti and the Economics of Excess

By appending the initials P.R.B. to The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, Rossetti put gold and gilding at the center of the newly founded Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s aesthetic program and public collective identity. The young painter-poet began working on the painting—the first to be publicly exhibited under the group’s banner—in the summer of 1848. The subject is an apocryphal scene from the Virgin’s childhood. A teenage Mary, modeled on Rossetti’s sister Christina, sits next to Saint Anne, who is assisting her with an embroidery. Anne turns her gaze downward to follow what her daughter’s hands are doing. Mary, meanwhile, fixedly scrutinizes her reference: a potted lily, propped up on a stack of heavy volumes (fig. 4). An angel is shown watering the plant. Saint Joachim appears in the background, standing before a trellis, whose intersecting wooden bars extend, cross-like, above a heavy stone balustrade, on top of which lie an oil lamp and cut rose, presumably left there by the patriarch. With a dove representing the Holy Spirit to his back, the industrious Saint Joachim tends to lush grape vines, which stretch from the left of the picture across the top, framing the entire scene.

The painting’s brilliant color scheme, non-hierarchical composition, and uniformly crisp renderings of individual elements pull the viewer’s attention in different directions. Influenced by what was then known about the working methods of Jan Van Eyck and more direct guidance provided by Ford Madox Brown and William Holman Hunt, Rossetti’s choice of materials and painting technique were well suited to the task he set for himself.12 Using small watercolor brushes, the artist applied paint in fine, translucent glazes over a white ground, ensuring both maximum detail and luminosity. Once hardened, the copal medium favored by Rossetti and fellow members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood lent The Girlhood of Mary Virgin a lustrous sheen, accentuating further still the painting’s luxurious, jewel-like appearance.13 The painting’s composition radically departs from the more balanced, clearly hierarchical ones favored by the Royal Academy, resting on distinctions between center and edge, light and dark. The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, by contrast, is structured around distinctions between the divine and earthly, surface and surplus. There is so much to look at, it is easy to forget that, for most of Rossetti’s contemporaries, gold was a material strictly reserved for frames.

According to art historian Elizabeth Prettejohn, Rossetti’s The Girlhood of Mary Virgin was likely inspired by early Italian painting, more specifically, the two “goldbacks” acquired in July 1848 by the National Gallery, then attributed to Taddeo Gaddi but now recognized as the work of Lorenzo Monaco.14 Unlike these two early fifteenth-century altarpiece side panels, however, The Girlhood of Mary Virgin does not show figures against a flat, gilt background. Rather, using a technique associated with thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Italian panel paintings and illuminated manuscripts called chrysographia, Rossetti applies gold much more selectively, highlighting only certain elements of the scene, such as the Virgin’s, Saint Anne’s, and the dove’s haloes; the angel’s small watering bottle; ornamental finishings on the oil lamp; strands of Mary’s hair; and the thin embroidery thread in her hand.15

The privileging of the direct, careful imitation of nature over the copying of conventionalized models, as exemplified by the Virgin, was a hallmark of Pre-Raphaelitism. But if Prettejohn’s interpretation of The Girlhood of Mary Virgin as a programmatic statement on artmaking is indeed correct, then Rossetti’s decision to show Mary, gold thread in hand, is undoubtedly deserving of more attention than it has received thus far.16 The Virgin-as-artist is literally gilding the lily, suggesting that, in Rossetti’s view, the making of art entailed a certain measure of excess, even waste. Further reinforcing this point, the artist employed shell gold not only for the expected, expressly divine elements of the scene, such as haloes, but also for ordinary, ostensibly worldly commodities. The saintly figures have none of the jewels and precious brocades typical of medieval and early Renaissance representations of the Holy Family.17 But the objects that surround them create a powerful impression of precious, refined luxury, as does the painting as a whole, thanks to its lustrous finish and elaborate, altarpiece-like frame.18

Compared to The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, Rossetti’s use of gold in his next major painting, Ecce Ancilla Domini! is more immediately noticeable, owing to the sparseness of the composition and the painting’s more limited color palette. Displayed for the first time at the National Institution Exhibition at the Portland Gallery in April 1850, the painting represents a later episode in the Virgin’s life, Gabriel’s announcement to Mary that she will become the mother of Jesus. Linking the artist’s unusual interpretation of the Annunciation and his previous painting in a narrative sequence, the lily-embellished embroidery from The Girlhood of Mary Virgin appears on the bottom right hanging over a narrow frame.

At first glance, the artist’s use of gold in Ecce Ancilla Domini! strikes one as fairly formulaic. Rossetti, that is, seems to have reserved its use for traditional, heavenly motifs: the dove’s beak and halo and the two nimbuses adorning the Virgin and Angel Gabriel (figs. 5 and 6).19 Technical studies have revealed a more complicated picture, however. Besides using shell gold to create these solid, reflective areas, the artist also mixed the pigment with standard non-metallic paints. The lilies, the dove’s wings, the angel’s face, and the flames at his feet all contain specks of gold that are mostly or indeed completely indiscernible to the naked eye (fig. 7).20 Rossetti is not exactly gilding the lily in this case, but squandering precious resources nonetheless. Despite the painting’s visual simplicity, Ecce Ancilla Domini! commanded a far greater expenditure of economic resources than one would expect or likely be seen as reasonable by professional artists.

How much Rossetti spent on materials is difficult to calculate. British law set the official price of gold at £4.25 per fine troy ounce—the equivalent of roughly 19 days of wages for a skilled tradesperson.21 Shell gold used by artists, which consisted of finely ground pure gold mixed with gum arabic, would have been considerably more expensive, however, owing to the extra costs involved in processing the material. But since trade catalogs and price lists for artists’ materials from this period do not provide the price of shell gold by weight—only per “shell” or “saucer”—exactly how much more expensive it was compared to other pigments must, unfortunately, remain a matter of conjecture.22

As contemporaneous textual evidence and technical studies of Rossetti’s artworks show, however, the young artist had already developed a pronounced taste for costly pigments. His limited technical skill and the uncertainty of finding buyers for his artworks did not deter him, for example, from employing expensive natural ultramarine, derived from lapis lazuli.23 In the first half of the nineteenth century, genuine ultramarine was approximately 17.5 times more expensive than the artificial version and 28 times more expensive in the second half, contributing to the popular belief that they were altogether different materials.24 The penchant for costly pigments among Pre-Raphaelites is also documented in what is likely one of Rossetti’s earliest experiments with oils (fig. 8). Executed by the recalcitrant young artist at the urging of his then teacher Ford Madox Brown, it would be easy to dismiss Bottles (1848) as mere juvenilia, unworthy of serious study. I would propose, however, that the painting can also be seen as a record of the artist’s impractical devotion to pricy pigments. For featured prominently in the center of the painting are three glass vials containing powdered pigments, the preferred format for valuable colors “to avoid waste.”25 Not that Rossetti himself was especially economical in the way he handled his materials.26

Rossetti’s disregard for rudimentary principles of responsible money management is especially striking when one considers that his family, while supportive of his decision to become an artist, could not assist him financially. Following his father’s resignation from his teaching position in 1843 owing to ill health, his mother took on private students, and his older sister Maria accepted a position as a governess. Money remained, however, an important source of concern for the Rossettis. The family’s situation improved in the winter of 1845 when his brother William Michael secured a position as a clerk at the Excise office. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that, save for his younger sister Christina who was charged with caring for her ailing father, Dante Gabriel was the only member of the Rossetti family without paid employment.27

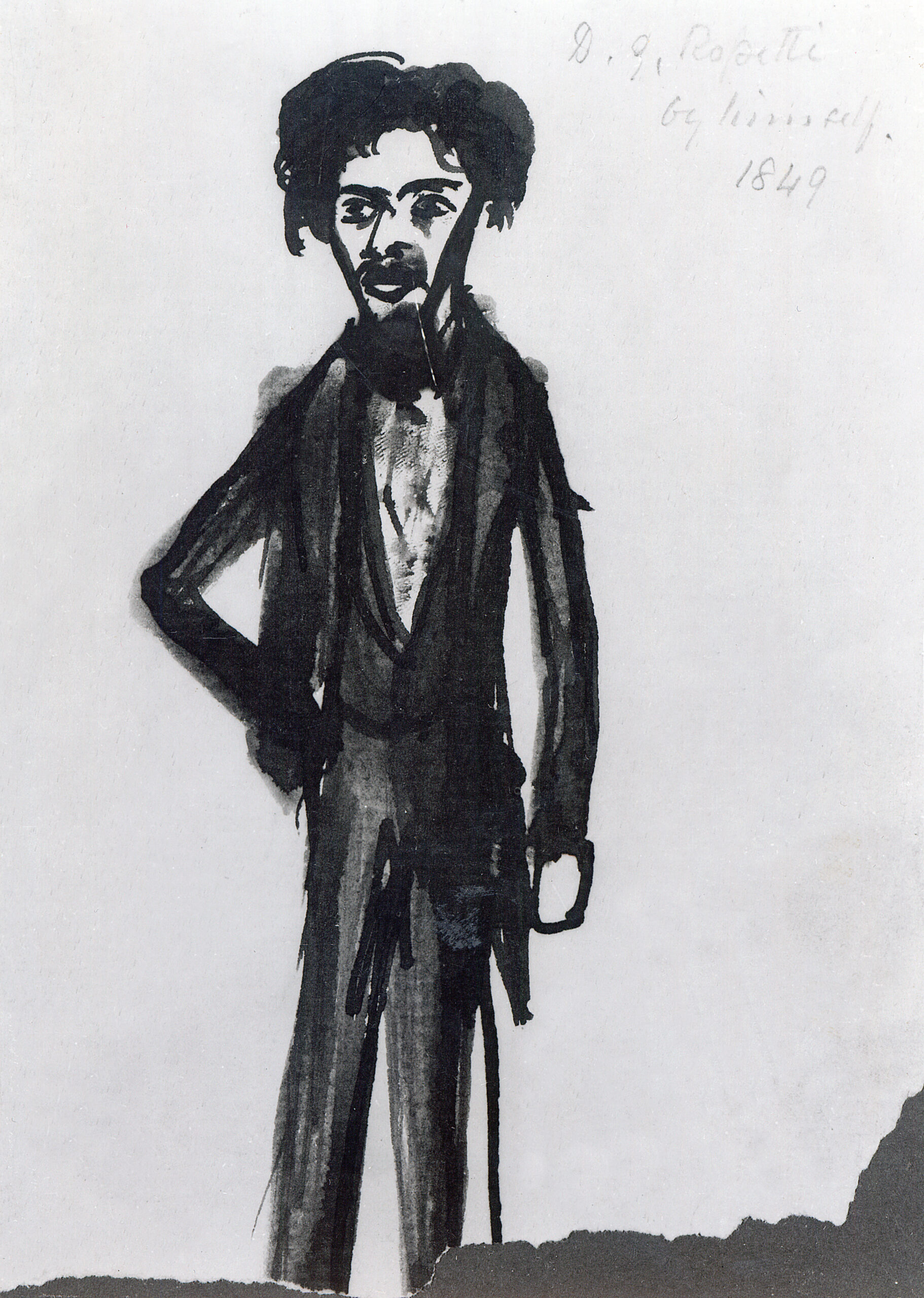

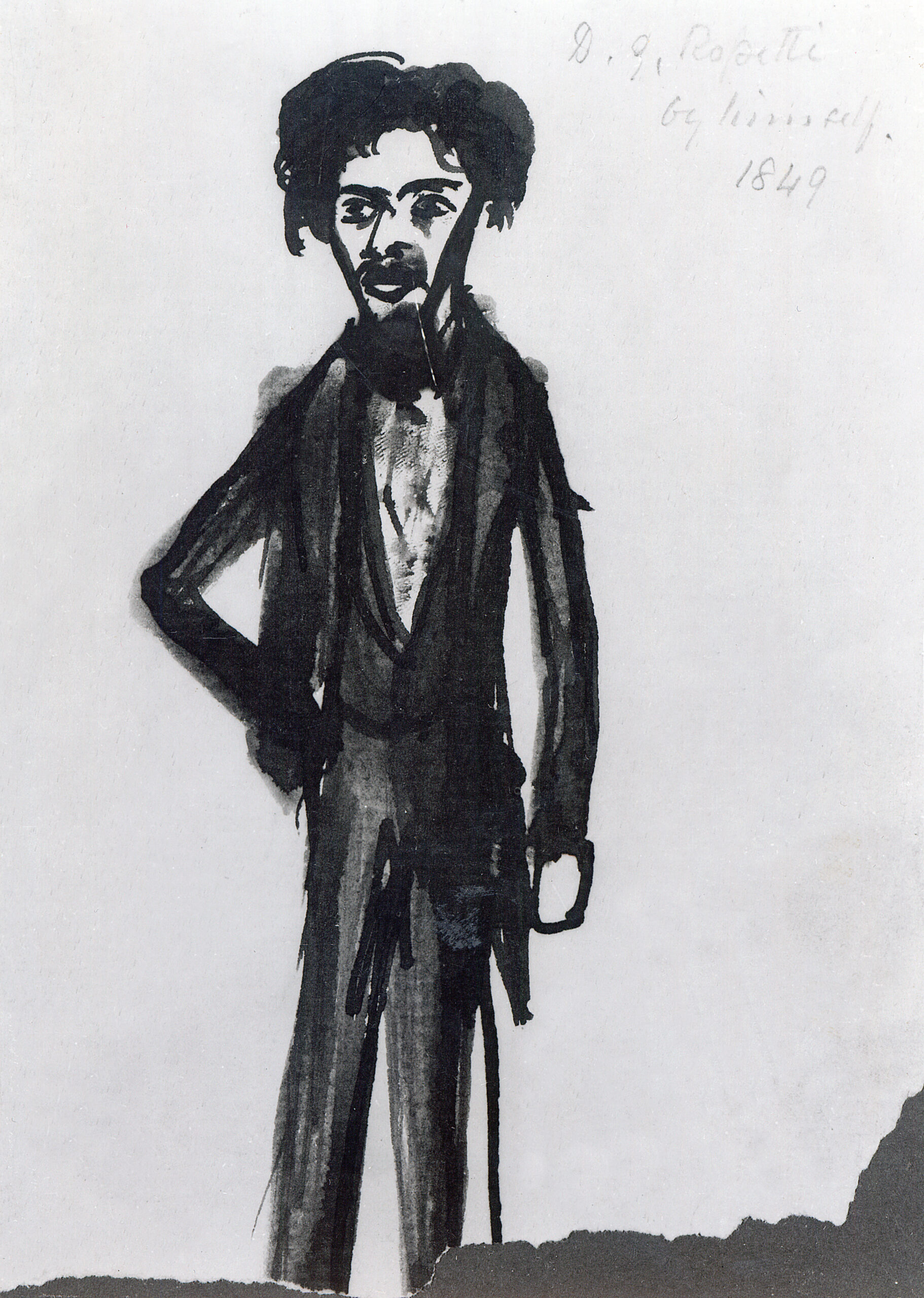

Certain aspects of the artist’s ascetic lifestyle were likely motivated more by necessity than virtue.28 Like Rossetti’s consumption of gold and other conspicuously expensive pigments, however, his pennilessness also had a markedly performative character. Recorded in an ink self-portrait, the young artist’s bedraggled appearance made a strong impression on fellow art students (fig. 9). “A bare throat, a falling, ill-kept collar, boots not over familiar with brushes, black and well-worn habiliments, including, not the ordinary frock or jacket ‘of the period,’ but a very loose dress-coat which had once been new—these were the outward and visible signs of a mood which cared even less for appearances than the art-student of those days were accustomed to care, which undoubtedly was little enough,” a former classmate from the Antique School recalled.29 Rossetti’s refusal to maintain a respectable middle-class appearance underscores how, in his mind, acts of consumption were guided by something other than the utilitarian motives normally outlined by nineteenth-century political economists and their popularizers. Rejecting the injunction to buy cheap and sell dear, the artist’s economic behavior pointed to the existence of another system of value, which took precedence over social customs and the ostensibly infrangible laws of the marketplace.

“Pondering Over the Nature of Money”: Monetary Events of the Mid-Century

The first half of the nineteenth century was a period of rapid economic growth and heightened social uncertainty, in response to which increasing numbers of politicians, intellectuals, journalists, and ordinary Britons turned to political economists for guidance. Writing in the early part of the 1830s, politician and author Edward Bulwer estimated that the new science had already left an indelible mark on the beliefs and customs of his fellow countrymen. “The spirit of the age demands political economy now, as it demanded moral theories before. Whoever will desire to know hereafter the character of our times, must find it in the philosophy of the Economists,” he remarked.30

By most traditional measures, however, this so-called philosophy was still very much in its infancy. The University of Oxford established the first professorship in political economy less than a decade earlier, in 1825, with what was then London University (now University College London) following shortly thereafter. Yet neither of those who occupied these positions, Nassau William Senior at Oxford and John Ramsay McCulloch at London University, nor any other of the leading British political economists of the era, had themselves been trained in the field. Likewise, many articles published in specialized journals continued to be written by amateurs without formal credentials or institutional affiliation. Political economy, in short, was not yet the fully professionalized, mathematical discipline it would later become.31

Coined by Karl Marx, the label “classical political economy” imputed far more coherence to the thinking of political economists of the era than it possessed in reality. Many key concepts had yet to be firmly defined, and polemics remained frequent, not least surrounding the central notion of economic value. Was value derived from the cost of labor, the cost of production more generally, or some other factor altogether? Was value a concrete thing, an intrinsic property of commodities, or merely a ratio? What was the relationship between value and price? Were they effectively one and the same, merely related to one another, or two entirely different things? What role, if any, did money play in these axiological calculations? And, finally, to what did money actually and truthfully owe its value?32 Confident that the most important questions had all been answered, John Stuart Mill famously observed in the first edition of Principles of Political Economy (1848) that “[h]appily, there is nothing in the laws of Value which remains for the present or any future writer to clear up; the theory of the subject is complete.”33 His confidence appears to have been genuine. But, as subsequent developments would show, it was also profoundly misplaced.

The period during which Rossetti created and exhibited his first paintings and, more generally, learned what it meant to be an artist was punctuated by several monetary events that pushed gold, political economy, and the “general problematic of value” to the forefront of public consciousness in ways more dramatic and confounding than ever before.34 Indeed, while it is hard to think of a place or time in history where gold was not closely associated with economic value, the mid-nineteenth century unquestionably represents an especially pivotal chapter within this broader narrative.35 In 1811–20, worldwide production of gold had decreased to a value of approximately £1.6 million annually, its lowest point since the late seventeenth century. By the 1830s, however, production had already more than doubled, reaching about £2.8 million annually, thanks to the increased production of Asian and Russian mines. In the following decades, following the influx of gold from California and then Australia, that number shot up to £28.1 million’s worth of the yellow metal a year.36 Never had the world—Britain especially—been more flush with gold. Nor, thanks to the passage of the Bank Charter Act of 1844 and the commercial crisis of 1847, had gold ever been more closely associated with money. No longer confined to the pages of The Economist or speeches on the floor of the British Parliament, discussions of the origins, essence, and functions of money were now the subject of newspaper headlines, caricatures, and poems.

Reflecting in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859) on one of the key monetary events of recent history, Karl Marx recalled how “in a parliamentary debate on Sir Robert Peel’s Bank Act of 1844 and 1845, [William] Gladstone remarked that not even love has made so many fools of men as the pondering over the nature of money. He spoke of Britons to Britons.”37 It is hard to know how much ordinary Britons understood of politicians’ “pondering over the nature of money.” The provisions of Peel’s Bank Act are too complex to rehearse here. Suffice it to say that, by restricting banknote issuing privileges to the Bank of England and the few other banks to whom the right had already been granted and mandating that these institutions restrict the number of banknotes printed to a fixed number based on the supply of gold in their coffers, British parliament reinforced the country’s existing gold standard and, in so doing, the financial as well as broader cultural connections between gold and money. To the question “What is a pound?” Peel famously offered the public the following deceptively simple answer: “a certain definite quantity of gold with a mark upon it to determine its weight and fineness.”38

Experts by and large agreed. Writing in the 1820s, McCulloch underlined how, far from being a purely arbitrary standard, as the proponents of paper money suggested, it was “their real fitness for a medium of exchange, which introduced the use of the precious metals,” thereby suggesting there was something natural, or preordained, about the country’s monetary standard. Further reinforcing the equivalence between money and gold, Robert William Dickinson later stipulated in an address to members of the North Devon Agricultural Association that “money, properly speaking, consists only of a certain quantity of precious metal,” whereas a banknote merely “brings to mind the quantity of money which the issuer promises to pay.”39 The architects and supporters of Peel’s Bank Act went a step further. In their view, the ultimate sign of the policy’s success would have been for the equivalency between gold and money, banknotes included, to become a fully naturalized mechanism, no more noteworthy than the wetness of rain or the transition from day to night.

Coinciding with Rossetti’s unenthusiastic studies at the Antique School, the commercial crisis of 1847 quickly put the country’s new gold-backed, ostensibly self-regulating monetary system to the test, however, leading many to wonder whether the Bank Act had been a terrible mistake.40 A poor harvest and unexpected spike in the price of cotton caused an increase in the cost of British imports, all of which had to be paid in precious gold. Described as a veritable mania, speculation in railway shares further exacerbated the situation by locking up a large percentage of the nation’s savings. Between January and April 1847, £5.6 million in gold bullion—38 percent of its entire reserves—left the coffers of the Bank of England.41 Required by the newly implemented Bank Act to replenish its metallic reserves to maintain the same level of note circulation, the Bank of England’s leadership increased the discount rate, meaning that merchants, bigger commercial houses, and brokers suddenly found it much more difficult to obtain credit. Unable to pay their debts, many of them went under, carrying a variety of financial institutions down with them.42 Fearing a generalized failure of the country’s banking system, depositors moved to withdraw their savings, further plunging the financial sector into crisis. In the end, the Parliament saw no other option but to temporarily suspend the Bank Act, allowing the Bank of England to extend credit beyond the normal limits its bullion reserve officially permitted, but not without causing ever more widespread “pondering over the nature of money.”

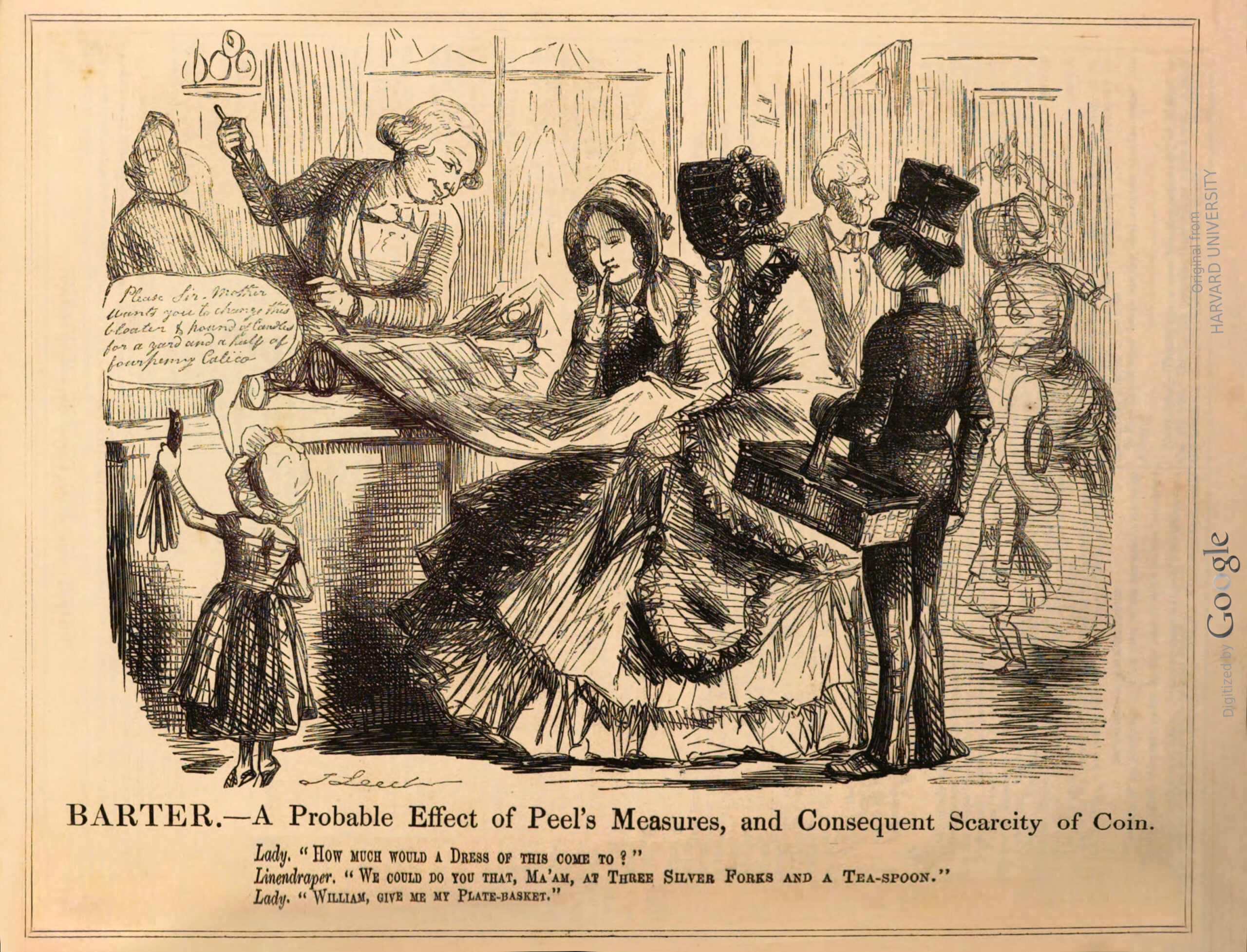

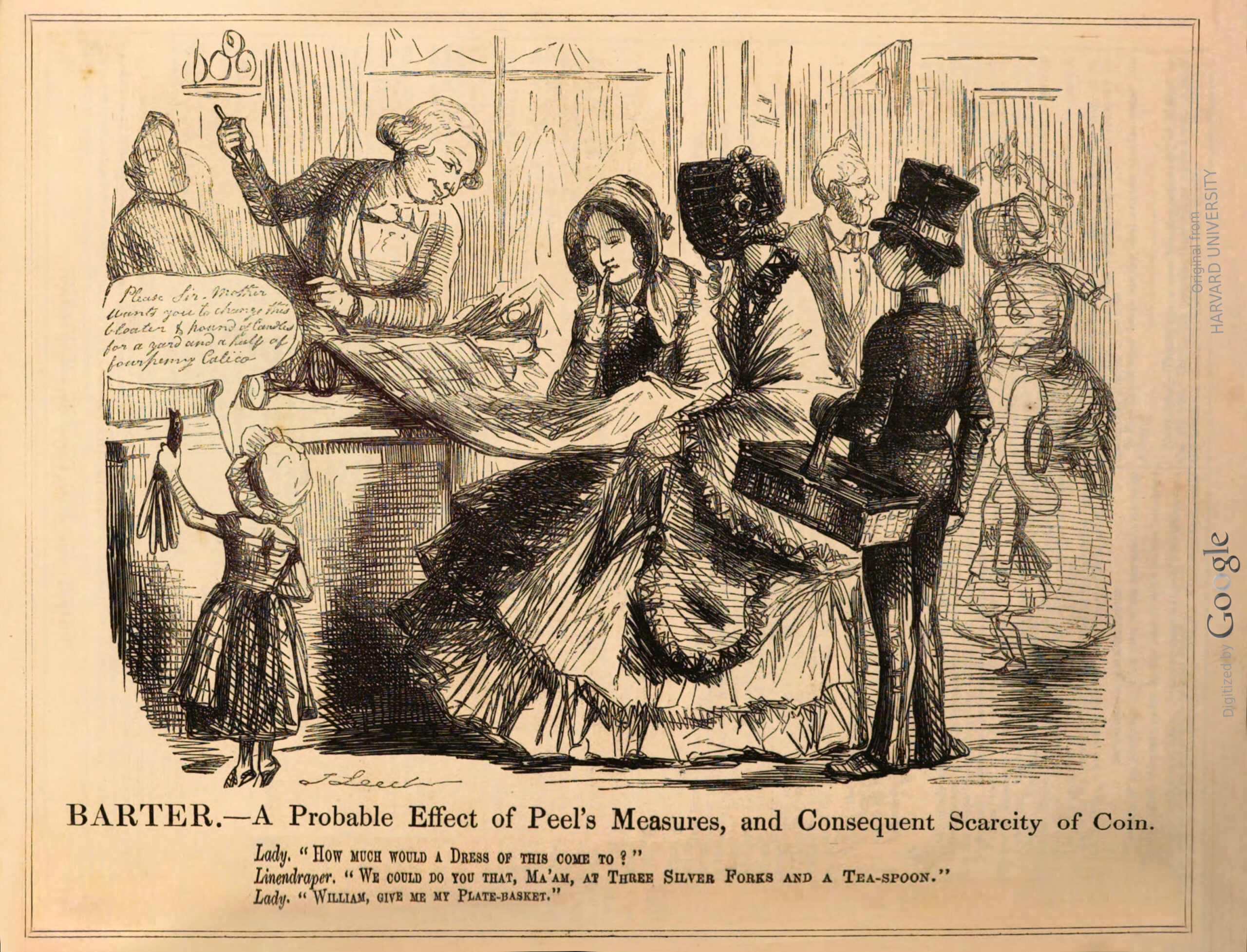

The effects of the crisis extended beyond merchants, brokers, and bankers. A caricature by John Leech published in the satirical magazine Punch in October 1847, at the height of the commercial crisis, draws attention to the impact on the supply of currency (fig. 10). Unable to rely on their regular pounds, shillings, and pence, modern Britons have regressed to an earlier, more primitive form of economic exchange, wherein gold watches and silver spoons are used as a means of payment. Asked by a well-heeled lady how much it would cost to make a dress out of the fabric displayed on the counter, Leech’s salesclerk quotes a price in plate: “three silver forks and a tea-spoon.”

By the time The Girlhood of Mary Virgin was exhibited in March 1849, the domestic shortage of gold was no longer. Far from fading into the background, however, events only further underlined the metal’s centrality to the economic organization of modern life. On January 24, 1848, carpenter James W. Marshall discovered gold while working on the property of Johann A. Sutter near Coloma, marking the beginning of the California gold rush. News of the discovery reached Britain in September 1848, with reports of diggers earning a year’s salary in a day or less capturing the imaginations of rich and poor alike.43 Announcements of steamships loaded with British citizens ready to make their fortunes in this new Eldorado soon followed. As a guide written for those undertaking the long journey remarked, the normally imperturbable John Bull was immediately transformed by the news of the discovery: “No sooner … does Jonathan touch him with his golden wand, than his whole frame becomes tremblingly alive; his wonted adventurous spirit returns to him, and he already fancies himself freighting his rich galleons in the bay of San Francisco.”44

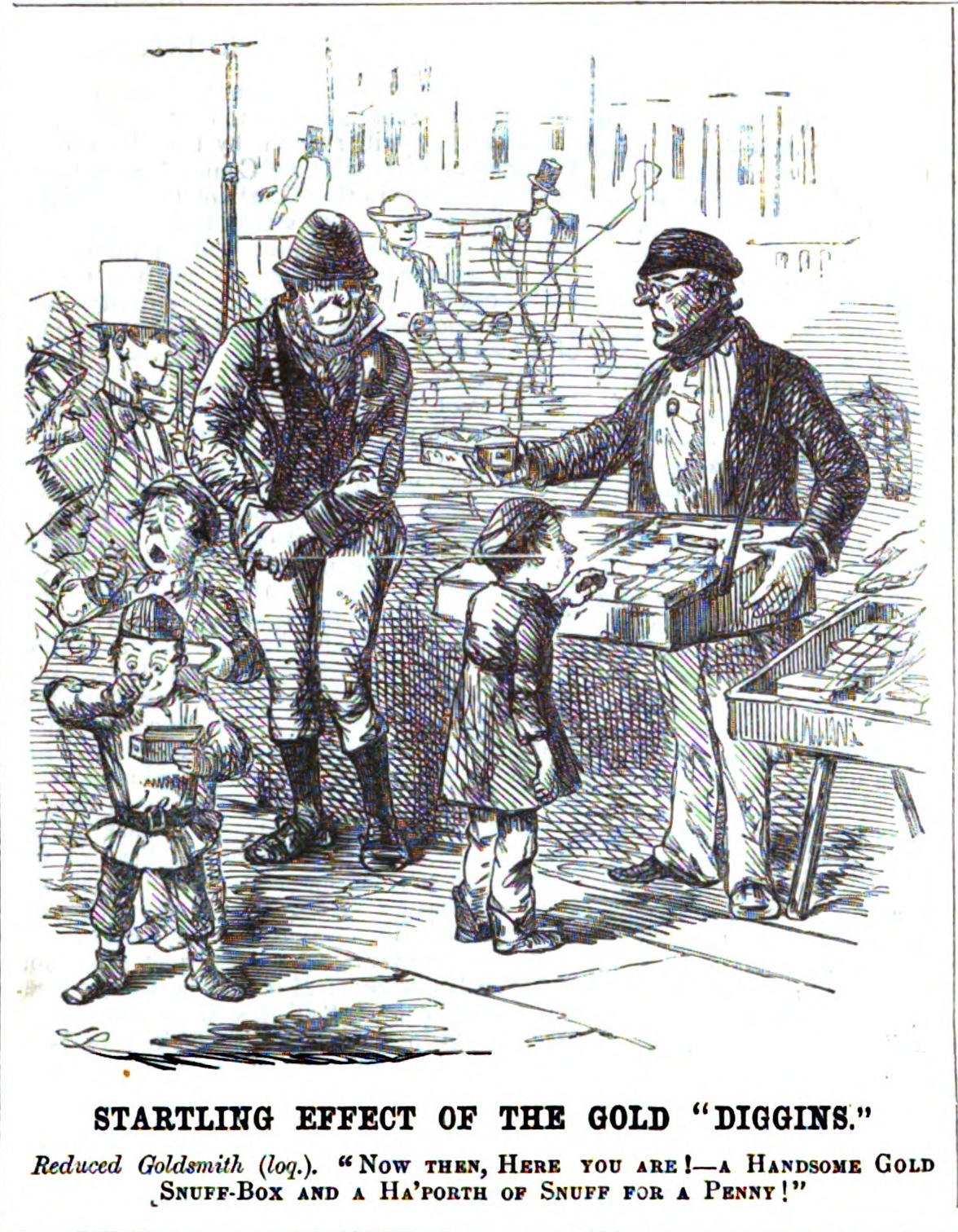

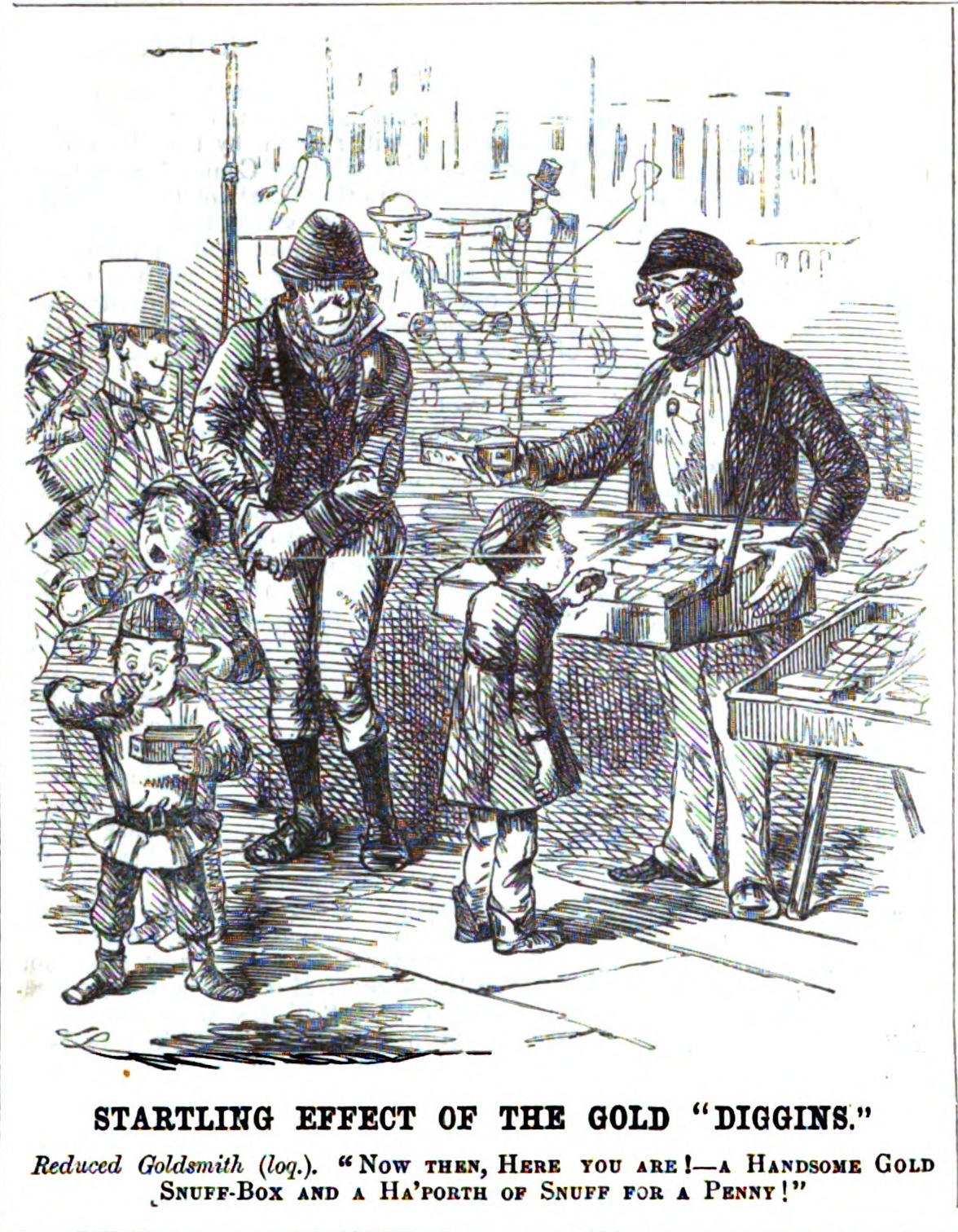

Contrary to the Commercial Crisis of 1847, where it was the exodus of gold that caused panic, the California and subsequent Australian gold rushes had many experts predicting a massive influx of the metal, with equally dire if opposite effects on the British economy.45 Indeed, Leech’s response to the gold “diggins” presents an almost mirror image of his previous caricature, commenting on the commercial crisis (fig. 11). Goldsmiths could generally take it for granted that their creations, no matter how elaborate and painstakingly crafted, would be melted down within a relatively short time. As Millard Meiss put it, “The life of the goldsmiths was thus somewhat like that of cooks: a relatively long period of preparation and a relatively short one of enjoyment.”46 In the imaginary scene crafted by Punch’s caricaturist, however, the tragedy is of a different order altogether. Because of the heightened supply of Australian gold, the plate that in the previous caricature served as a means of payment has now lost all its value. The goldsmith sells his wares for a penny, carrying them around his neck like an itinerant fruit seller.

It would not be long before the pressures that motivated Britons to undertake these long hazardous voyages to make their fortunes were felt in Rossetti’s immediate circle. In July 1852, Thomas Woolner, one of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s founding members, left Britain for the gold mines of Australia.47 The sculptor, who served as a model for the angel in Ecce Ancilla Domini!, quickly became disenchanted, however, with the pragmatic realities of gold mining. “I see no very sparkling fortune in the future,” he noted in his diary, adding that, in Australia, “nothing but primitive necessities are understood and those of the coarsest kind, sleeping, eating, working, eating and sleeping again, this on and on without a change unless for a fight or drunkenness.”48 Other members of Britain’s artistic and literary elite who, struggling to make a living in the metropole, opted for this life of “primitive necessities” included the painters William Strutt and Bernhard Smith, the draughtsman and illuminator Edward LaTrobe Batemen, the poet Richard Henry Horne, and novelist Henry Kingsley. For Rossetti, who had expressed interest in taking a job at a railway telegraph company if his career as an artist did not soon take off, the decision to treat gold as an artistic medium as opposed to an alternate source of livelihood was meaningful in and of itself.49

In fact, far from diverting attention from gold’s economic significance, Rossetti’s references to the artistic traditions of the distant past frequently only further highlighted it. For example, it was a common supposition among members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood that medieval and early Renaissance artists were compelled by their deep and abiding religious faith to use the most refined and costly materials in their work. This interpretation of sacred art gained increasing currency in the 1840s thanks to Mary Merrifield’s annotated translation of Cennino Cennini’s A Treatise on Painting (1844) and Anna Jameson’s widely read Memoirs of the Early Italian Painters and of the Progress of Painting, from Cimabue to Bassano (1845), a copy of which was gifted to Rossetti by his godfather.50 That Rossetti was familiar with this anti-utilitarian, sacrificial conception of art-making is furthermore demonstrated by the introduction he prepared for John Orchard’s unfinished “A Dialogue on Art,” published in the May 1850 edition of the Pre-Raphaelite journal, The Germ, where he quoted the deceased author’s notes, explaining that, in the distant past “gilding, &c., [was] disposed of on the ground of the old piety using the most precious materials as the most religious and worthy of them.”51 Interpreted in this manner, Rossetti’s gilt creations emerge as a concrete, tangible measure of his devotion both to Art and to God, as opposed to some more stereotypical expression of bohemianism and youthful financial irresponsibility.52

That being said, Rossetti’s selection of godly fourteenth- or fifteenth-century artists as role models only takes on its full significance when we consider how singularly ill-suited these figures were for the role. Contrary to his pious forefathers, who produced art almost exclusively on commission, Rossetti was expected to make art for the market and, unlike a Giotto or Fra Angelico, had to buy his own gold and ultramarine.53 By drawing attention to, rather than simply ignoring, the metal’s historical as well as contemporary associations with wealth and money and the mismatch between early Renaissance and Victorian economic practices, Rossetti’s paintings destabilize mainstream assumptions about economic value in what was a pivotal era in the history of economic and social thought. The artist’s creation of artworks that glimmer and shine was partly aspirational—an instance of what Thorstein Veblen called “pecuniary emulation.”54 But it was also oppositional. Through his dress, art, and dogged refusal to “get a real job,” Rossetti renounced accepted, middle-class forms of respectability. By appropriating visual expressions of prestige, wealth, and money, he aimed to increase recognition of other forms of value and thus arrest what he and many of his contemporaries perceived as the unrelenting subjection of society, nature, and art to the purportedly scientific teachings of political economists.

“The Possession of the Valuable by the Valiant”: Ruskin’s Political Economy and The Gold Question

Focused on the connection between Rossetti’s paintings and the art of the distant past, critics’ responses to The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Ecce Ancilla Domini! ignored more proximate resonances with the gold standard and gold rush. For most, the paintings’ gold haloes and other shimmering accents offered visual confirmation of Rossetti’s desire to revive the art of the Quattrocento. In fact, those sympathetic to the artist’s experimental style typically left it at that, omitting any specific reference to the artist’s use of gold. For others more circumspect if not outright hostile to the artist’s innovative style, the migration of gold from the frame to the canvas emblematized everything wrong with the recently founded Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Indicative in their view of the group’s servile allegiance to the past, Rossetti’s use of gold was the focus of special opprobrium in more than one review. “Mr. Rosetti [sic], a young artist evidently of talent and originality, carries this predilection for the medieval so far that his ‘Salutation of the Virgin’ might be a leaf torn out of a missal. The figures are tall and lank, the expression of the girlish Virgin is intense to the highest degree, but there is nothing human in its intensity. The association with the missal is kept up, as with the earliest masters, by the employment of real gold for the halo,” remarked the critic from the Times.55 Writing ostensibly about the Pre-Raphaelites in general, The Atheneum’s art critic drew a similar conclusion: “An unintelligent imitation of the mere technicalities of old Art—golden glories, fanciful scribblings on the frames, and other infantine absurdities—constitutes all its claim.”56 In short, if gold was to make a comeback, it would inevitably be at the expense of originality, depth, Protestant asceticism, and pure common sense, Rossetti’s detractors warned.

If scholars have until lately almost entirely ignored Rossetti’s experiments with the “meretricious” metal, it is not, therefore, because this aspect of the artist’s painting went completely unnoticed. John Ruskin and the heavy influence his interpretation of Pre-Raphaelitism has exerted on historians of nineteenth-century British art, I would suggest, bears the bulk of the responsibility. The richness of his insights as well as the remarkable consistency of his analysis have lent his writings an art-historical authority unmatched by any other contemporaneous source. His failure to bring attention to the significance of gilding in Pre-Raphaelite painting is more than simply curious, therefore; it has also had measurable, long-lasting effects on scholarly interpretations of these artworks.

Published in the Times on May 13, 1851, Ruskin’s first public statement on the Pre-Raphaelites attempts to situate their art within a broader social context. More specifically, seeking to challenge criticisms of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood emphasizing the members’ mindless imitation of old masters, the “author of The Modern Painters” aimed to convince readers that the young artists’ most immediate connection to the past had nothing to do with materials or even subject matter, but with their distinctly empirical, laser-focused way of visually engaging with and laboriously representing the world around them. “As far as I can judge of their aim—for, as I said, I do not know the men themselves—the pre-Raphaelites intend to surrender no advantage which the knowledge or inventions of the present time can afford to their art. They intend to return to early days in this one point only—that, as far as in them lies, they will draw either what they see, or what they suppose might have been the actual facts of the scene they desire to represent, irrespective of any conventional rules of picture making,” he explained.57

Ruskin closely sympathized with the aims of the group, in particular with what he identified as their uniquely naturalistic renderings of intrinsically abstract, spiritual concepts. The time and effort artists invested in studying and patiently reproducing nature were also singularly important in his view.58 The critic returned to this point in his 1853 lecture, “Pre-Raphaelitism”:

Pre-Raphaelitism has but one principle, that of absolute, uncompromising truth in all that it does, obtained by working everything, down to the most minute detail, from nature, and from nature only. Every Pre-Raphaelite landscape background is painted to the last touch, in the open air, from the thing itself. Every Pre-Raphaelite figure, however studied in expression, is a true portrait of some living person. Every minute accessory is painted in the same manner. And one of the chief reasons for the violent opposition with which the school has been attacked by other artists, is the enormous cost of care and labour which such a system demands from those who adopt it, in contradistinction to the present slovenly and imperfect style.59

Ruskin’s pivot to political economy proper still lay a few years ahead. It began with a series of lectures entitled “The Political Economy of Art,” delivered during the Art Treasures Exhibition in Manchester (1857), and later published under the title A Joy Forever. From wanting to nail down a concept of aesthetic value independent of economic value, Ruskin gradually progressed to directly attacking mainstream political economists and then devising his own alternative political economy. This was accomplished through a series of articles in The Cornhill Magazine and Fraser’s Magazine, later published under the titles Unto this Last (1862) and Munera Pulveris (1872), respectively. As the above-quoted passage attests, however, Ruskin had already started thinking about art and the world, more broadly, in explicitly economic terms. Indeed, as the late nineteenth-century political economist and social reformer John Atkinson Hobson pointedly noted, Ruskin himself had repeatedly claimed “to be first and above all else a Political Economist.”60

Laying at the intersection of the economic and the aesthetic, gold emerges early on as a frequent object of consideration in Ruskin’s writings. As we will see, however, the critic’s interest in the precious metal both expanded and intensified with his turn toward political economy. Presented with the opportunity to write about Rossetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini! in 1878, however, the critic again overlooked the presence of gilding. “If we are to know him for an angel at all, it must be by his face, which is that simply of youthful, but grave, manhood. He is neither transparent in body, luminous in presence, nor auriferous in apparel,” he remarked, conveniently ignoring the golden nimbus. “[The Virgin] herself is an English, not a Jewish girl,” he also noted, further underscoring the everyday veracity of the scene.61 Committed to demonstrating Pre-Raphaelitism’s contemporary, specifically Victorian significance, Ruskin continued to strategically gloss over that aspect of Pre-Raphaelite painting that struck critics as most patently medieval. Stretching a period of nearly thirty years, the critic’s writings on Pre-Raphaelitism were, indeed, remarkably coherent. Readers of this latest lecture would have had no reason to suspect that Ruskin and Rossetti were once intimate intellectual companions, that their friendship had abruptly ended, or that, at the time of their rupture, the art critic had almost entirely stopped writing about art to concentrate instead on political economy.

Rossetti and Ruskin first met in 1854. And while not entirely free from conflict, the friendship that followed seems to have been based on genuine, reciprocal admiration and affection. Economic exchanges between the two men played a central role in further solidifying their relationship. As Elizabeth Helsinger observes, the men’s blurring of boundaries between gifts and purchases, between the social and the professional, “helped create a counter-economy of Pre-Raphaelite art within the Victorian art market.” 62 Indeed, more than their shared love of medieval and early Renaissance art, it was, I would argue, the two men’s shared recognition that the standards of value that structured Victorian economic and social life were open to critique and reevaluation that, in the first instance, most intimately linked the artist and critic. What Rossetti sought to achieve in his twenties, through the conspicuous, counter-cultural display of traditional symbols of economic value, Ruskin pursued most overtly in his forties, through a “guerrilla” political economy, which adopted in the exterior trappings of the very science it sought to upend.

In the scholarship tracking the ups and downs of the men’s relationship, Rossetti’s reputed disinterest in Ruskin’s program for broad social and political reform never fails to garner attention. “As to Ruskin’s ten years’ rest, I do not know about his writing, but I will answer for my reading, if he only writes like his article in the Cornhill this month. Who could read it, or anything about such bosh!” Rossetti remarked in a letter to William Allingham.63 However, Ruskin’s failure to appreciate the significance of Rossetti’s use of gold gestures toward an earlier and more fundamental misalignment in the two men’s approaches to the challenge of reimagining economic value.

Ruskin’s writings on political economy resist easy synthesis. Focusing, however, on the critic-cum-political economist’s theory of value and miscellaneous statements on gold, a clearer picture of his ideas and larger ambitions emerges. As Ruskin suggested in a letter to Elizabeth Barrett Browning, his decision to tackle the great economic debates of the day stemmed from “the disappointment of discovered uselessness—having come to see the great fact that great Art is of no real use to anybody but the next great Artist. That it is wholly invisible to people in general—for the present, and that to get anybody to see it, one must begin at the other end, with moral education of the people.”64 Indeed, contrary to Rossetti, Ruskin believed that nothing meaningful would ever be achieved in art without first fundamentally redefining economic value, gold, and their relationship to one another.

At the heart of mid-nineteenth-century political economists’ attempts to define the source and nature of economic value lay a desire, Robert Heilbroner explains, “to tie the surface phenomena of economic life to some inner structure or order.”65 But before this inner structure or order could be defined, it was essential, political economists insisted, to first properly ascertain their area of focus. According to John Stuart Mill, for example, the most renowned British political economist at the time and one of Ruskin’s primary targets, use values—that is, objects’ inherent ability to “satisfy a desire, or serve a purpose”—and their relative evaluations fell outside the realm of political economy.66 Unlike the philosopher or the moralist, in other words, the political economist should not concern him- or herself with evaluating the kinds of desires or purposes that commodities satisfied. All commodities and satisfactions were equally justifiable. In fact, as the political economist explained, the true focus of the discipline was not use value at all, but value in exchange. “The word Value, when used without adjunct, always means, in political economy, value in exchange; or as it has been called by Adam Smith and his successors, exchangeable value, a phrase which no amount of authority that can be quoted for it can make other than bad English,” Mill quipped.67 Following in the footsteps of David Ricardo, the political economist maintained that the cost of labor had a decisive influence on the price, or exchange value, of commodities. Unlike his predecessor, however, he proposed that the value of things was only a ratio. “[T]he value of a commodity,” Mill clarified, “is not a name for an inherent and substantive quality of the thing itself, but means the quantity of other things which can be obtained in exchange for it.”68

As historians of economic thought have pointed out, Ruskin’s analyses of Mill and other orthodox political economists of the era suppress all theoretical complexity to the point of rendering their ideas virtually unrecognizable.69 Ruskin’s critique, however, was not so much aimed at a particular individual or theory as it was aimed at the fundamental premises of the science. In a letter to Dr. John Brown, he observed, “The Science of Political Economy is a lie,—wholly and to the very root …. To this ‘science,’ and to this alone (the professed and organised pursuit of Money) is owing All the evil of modern days. I say All.”70

The primordial lie of political economy from which all others stemmed, according to Ruskin, was the discipline’s narrowly utilitarian and shortsighted theory of value. Far from being something relative, as Mill suggested, economic value was something intrinsic and fixed, applicable only to that which “avail[s] towards life,” Ruskin asserted in Unto This Last.71 The critic’s definition of wealth, elsewhere in the same text, as “the possession of the valuable by the valiant” further underscores his opposition to commonplace assumptions in the field.72 Contrary to Mill, for whom questions of distribution were fundamentally ethical and political in nature and thus fell outside the realm of political economy proper, how wealth was distributed and the ends to which it was deployed remained issues of primary importance for Ruskin. Presented by orthodox political economists as a self-evident necessity of scientific research, the distinction between ought and is or, as he saw it, moral agnosticism of the science’s main exponents was especially troublesome in Ruskin’s view.73

Scattered among A Joy Forever, Unto this Last, Munera Pulveris, and other shorter texts, Ruskin’s reflections on gold and money provide additional insight into the critic’s overarching project of reinventing the “dismal science.”74 This was hardly his first time, however, meditating on the subject. In The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), he argued that the superficial tinsel and glitter of Catholic churches and the general overuse of gilding in the decorative and industrial arts gravely undermined gold’s appeal. “[I]t is one of the most abused means of magnificence we possess,” he observed. As he confessed, however, his “love for old and saintly art” was too great to allow him “to part with its burnished field, or radiant nimbus.” How artists employed the material made all the difference. Gilding, he underscored, should be used sparingly and with respect “to express magnificence, or sacredness, and not in lavish vanity, or in sign painting.”75 Rossetti’s intensely devout and idealistic use of gilding in The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Ecce Ancilla Domini! illustrated Ruskin’s stance perfectly, making the critic’s silence on the matter all the more surprising, especially as time went on.

By the late 1850s and ‘60s, however, Ruskin’s interest in gold primarily lay elsewhere. More specifically, responding both to the ever-widening variety of gilt surfaces and the momentous monetary events of the times, the amateur political economist tasked himself with dismantling the precious metal’s privileged association with money and economic value. Metaphor, alliteration, parody, hyperbole, evocative imagery—Ruskin employed every literary device at his disposal in the service of this starry-eyed goal. In a key passage in A Joy Forever, he observed, for example:

… you always have to find your artist, not to make him; you can’t manufacture him, any more than you can manufacture gold. You can find him, and refine him: you dig him out as he lies nugget-fashion in the mountain-stream; you bring him home; and you make him into current coin, or household plate, but not one grain of him can you originally produce. A certain quantity of art-intellect is born annually in every nation, greater or less according to the nature and cultivation of the nation or race of men; but a perfectly fixed quantity annually, not increaseable by one grain.76

Ruskin’s goal was not to convince the audience that artists are valuable in the same way that gold is valuable, but as he explained in a later text, that “the persons themselves are the wealth,” meaning that “the true veins of wealth are purple—and not in Rock, but in Flesh.”77 Turning the vivid imagery of the Californian and Australian gold rushes against itself, Ruskin used gold as a metaphor, a glittering rhetorical contrivance, to direct the public’s attention toward something else considered more valuable that exceeded the self-imposed limits of the period’s dominant economic theories.

What, then, of the gold standard and the metal’s concrete material connections to money? Here, too, Ruskin’s views strayed far outside the mainstream. In sharp contrast, for instance, to those public voices that suggested that nations’ adoption of the gold standard was an indication of their racial superiority, the novice political economist took the position that “[t]he use of substances of intrinsic value as the materials of a currency, is a barbarism;—a remnant of the conditions of barter, which alone render commerce possible among savage nations.”78 That the value of the country’s currency could fluctuate depending on any number of accidental conditions, such as the balance of trade or new discoveries of gold, was pure madness, he furthermore insisted. For in reality, money was not a thing at all but rather a “documentary claim” to the possession of valuable things or, as he wrote elsewhere, a “token of right.”79

For gold to assume its true and proper function, the public, Ruskin believed, first needed to learn to think about and see the precious metal differently. Lest Leech’s disheartening caricature of the goldsmith’s profession become a reality, however, it was important that gold’s economic value not be completely eroded. This value, Ruskin contended, lay not in traditional measures, such as the cost of labor, demand, or some combination of the two, but in the precious metal’s unique material properties and fitness to serve specific aesthetic functions. As he explained, “[G]old has been given us, among other things, that we might put beautiful work into its imperishable splendour, and that the artists who have the most wilful fancies may have a material which will drag out, and beat out, as their dreams require, and will hold itself together with fantastic tenacity, whatever rare and delicate service they set it upon.”80 The goldsmith’s work provided, moreover, excellent training for the painter and sculptor, as demonstrated by the creations of Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo, Leonardo, and Ghiberti, all of whom were goldsmiths or trained by goldsmiths. The wealthy patrons should, therefore, feel perfectly at ease in purchasing metalwork. For as Ruskin explained, “if they ask for good art in it, they may be sure in buying gold and silver plate that they are enforcing useful education on young artists.”81 Indeed, contrary to many Victorian social thinkers, such as Samuel Smiles, who viewed abstinence and thrift as core virtues, Ruskin encouraged those with sufficient resources to spend lavishly, even sacrificially, provided, that is, that what they purchased possessed intrinsic value and genuinely availed toward life.82

As Supritha Rajan rightly notes, Ruskin viewed the social body as resting on “a system of reciprocal self-sacrifice.”83 The nature of these sacrifices differed, however, based on whether one was a wealthy person or a worker: whereas the worker sacrificed labor, the rich man or woman sacrificed, in the main, money. Hints of Ruskin’s fundamentally conservative, functionalist view of society are already discernible in The Seven Lamps of Architecture. “[T]hough it may not be necessarily the interest of religion to admit the service of the arts,” he observed, “the arts will never flourish until they have been primarily devoted to that service—devoted, both by the architect and employer; by the one in scrupulous, earnest, affectionate design; by the other in expenditure at least more frank, at least less calculating, than that which he would admit in the indulgence of his own private feelings.”84 It comes as no surprise that Ruskin’s writings on political economy were initially targeted at the wealthy, for it was their impoverished definition of value, he believed, that were most directly to blame for the degradation of art and thus in most urgent need of reform. “A rich man,” he noted, “ought to be continually examining how he may spend his money for the advantage of others.”85 But what of the worker’s spending? Or, more specifically, the artist’s?

More than a failure of aesthetic appreciation, Ruskin’s failure to appreciate the significance of Rossetti’s golden illuminations was a failure of the imagination. According to his economic program, artists’ value and valiance were to be measured by the quality of their observational abilities and craftsmanship and the beauty of what they produced. That an artist would, like Rossetti, performatively sacrifice his meager savings on the most expensive pigments was simply inconceivable. Put differently, as workers, artists’ contributions could never be conceptual in nature. It is telling, for instance, that to address the problem of artists using low-quality, impermanent materials in the pursuit of higher profits, the social thinker proposed handing over their production to “our paternal government,” thus shielding artists from market pressures altogether.86 Such a measure would also, however, curtail artists’ agency—their ability as producers and consumers to devise their own practical political economy of art.

Rossetti’s Sancta Lilias (1874): Luster and Labor in the Aesthetic Era

Characterized by mainstream political economists as “aesthetic twaddle,” “utter imbecility,” and “one of the most melancholy spectacles, intellectually speaking, that we have ever witnessed,” to only quote a few characteristic barbs, Ruskin’s articles in The Cornhill Magazine immediately raised a storm of protest.87 This was to be expected. By fighting political economists on their own terrain, as it were, the critic opened himself up to much harsher rebukes than if he had stuck to criticizing them from the margins. His uninvited incursion into the world of political economy presented an ideal opportunity for more established members of the intellectual community to defend their status as genuine professionals at the command of specialized scientific knowledge. When all was said and done, the neophyte’s quixotic efforts at reforming political economy likely only lent greater credence to the very principles he sought to challenge.88

Rossetti ran analogous risks with his increasingly flashy use of gold. From the 1860s onwards, the artist’s ostensibly counter-cultural, anti-capitalist expenditure of economic resources became harder to distinguish from straightforward exaltations of luxury. On the surface, at least, it appeared as though many of these later gilded artworks only furthered the metal’s dominant cultural associations with economic value and money, as evidenced, most notably, by the painting Rossetti’s Sancta Lilias (1874). At once too flat and not flat enough, abstract and object-like, the painting the artist once called his “gilded picture” performs more like money than an autonomous work of art.89

The painting’s abstruse subject is partly to blame. Modeled by Alexa Wilding, the central female figure represents the “blessed damozel,” a subject originally explored by the artist in a poem by the same title, written when he was eighteen or nineteen years old and later published in The Germ. Revised multiple times over the course of Rossetti’s career, the poem centers on a couple whose love for one another transcends physical distance, even death. The imparadised damsel, with long hair “yellow like ripe corn,” tries to catch a glimpse of her lover, who remains down below among the living. Leaning over the gold bar of Heaven, she waits and weeps for her lover, ignoring the new delights of paradise that surround her.90

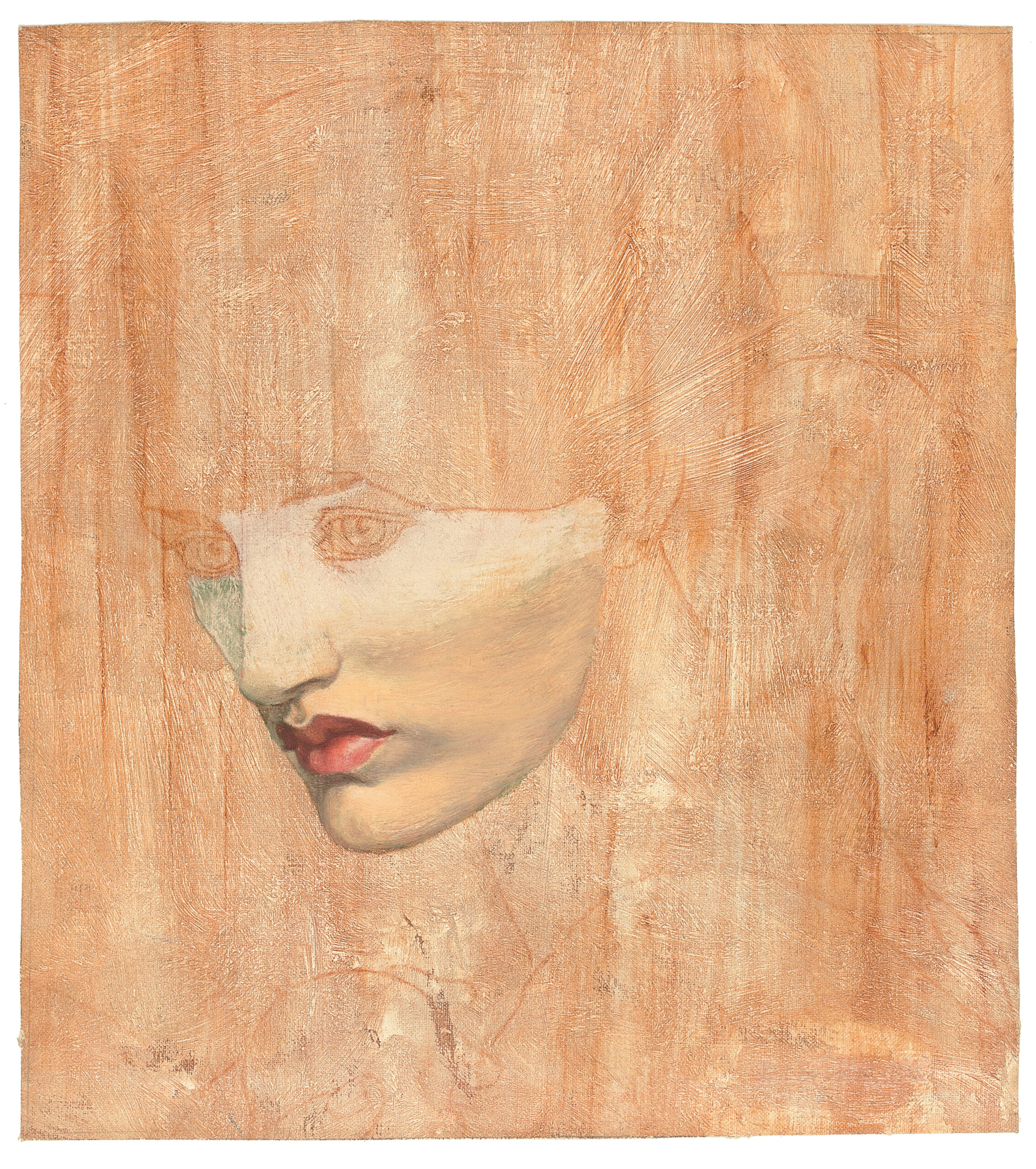

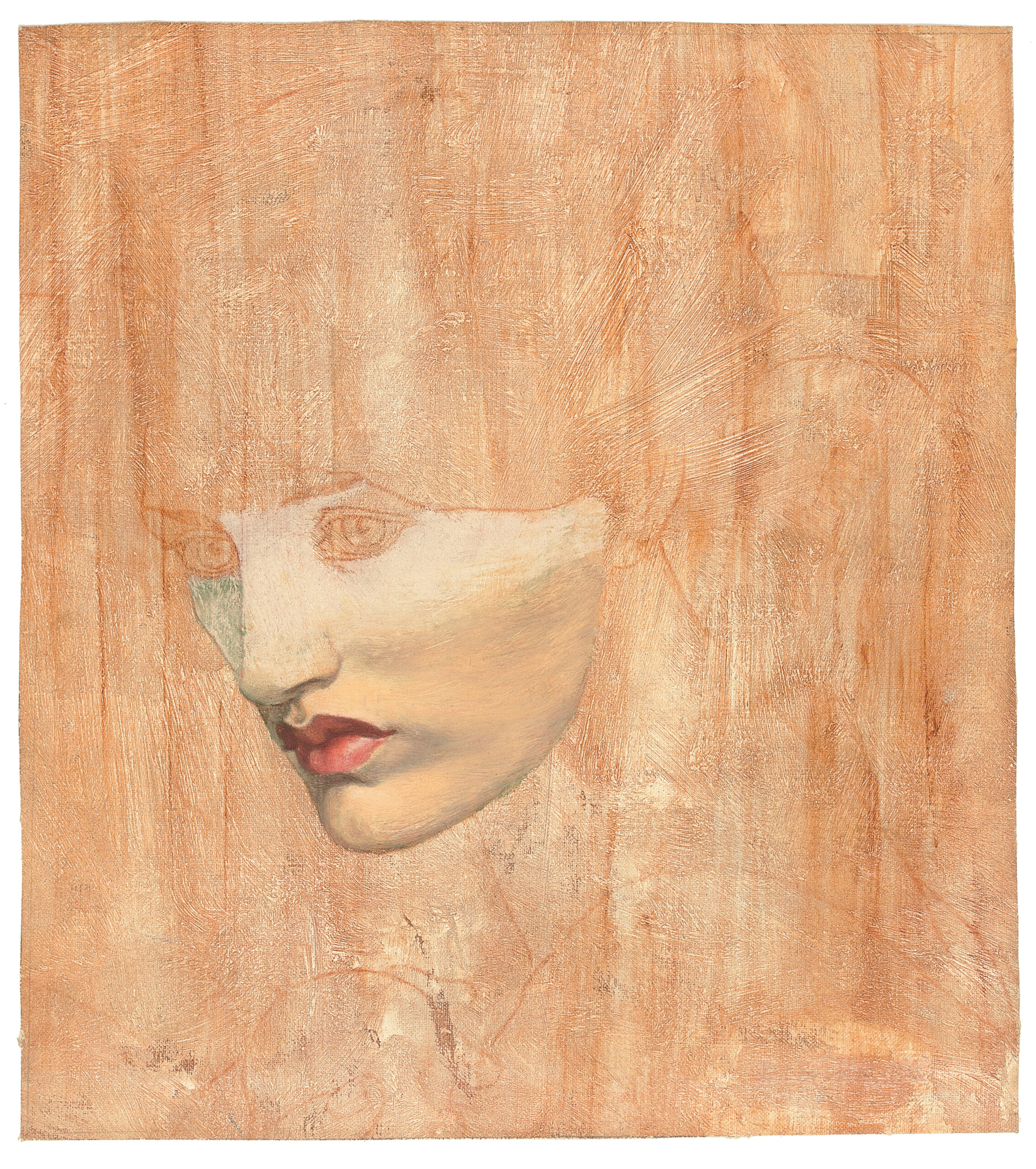

After nearly finishing the lady’s head and hands and beginning the bust, Rossetti abandoned the painting and started over again, eventually producing the version of the painting that is now in the collections of Harvard University’s Fogg Museum (fig.12).91 He returned to the original canvas in or around 1873. After first cutting down its size, Rossetti hired the gilder employed by his favorite frame makers, Foord and Dickinson, to apply gold leaf on “the parts where the red ground of the canvas [was] left, both dress & background.”92 He added the yellow irises and also reworked the hair. Finally, Rossetti painted a gauzy yellow dress over the gilt bust area. A rough idea of what the canvas looked like before its gilding can be gleaned from other unfinished works by the artist, such as Head of Proserpine (1872) (fig. 13).

Challenging at the same time the illusion of three-dimensionality and the usual silence surrounding financial matters in rarified artistic milieus, Rossetti’s use of gold in Sancta Lilias provides an unusually explicit counterpoint to the sacrificial theory of value the artist espoused in his early years. Following The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Ecce Ancilla Domini!, Rossetti employed gold almost exclusively to create flat gilt backgrounds in the style of early Italian art.93 Only the Cardiff altarpiece, however, is explicitly religious in nature (fig. 14). More often, Rossetti used gold leaf to create secular, even sensual, interpretations of the traditional “goldback,” including portraits and more finished allegorical artworks, featuring bona fide gold leaf (figs. 15–19).94 The tensions between the sacred and the profane are especially pronounced in the latter, where the lustrous quality of the oil paint and the beauty of the paintings’ colors play off of and accentuate the gold background.

A lot had changed since Rossetti’s early days as a lanky, penniless artist. By 1854, the original members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had parted ways. Roughly five years later, Rossetti radically changed his style, abandoning minutely detailed renderings of biblical and literary subjects in favor of sensuous, non-narrative celebrations of feminine beauty, abstract surface patterning, color, and shine. And contrary to his earlier paintings, these newer ones of “beautiful women with floral adjuncts,” as his brother described them, found no shortage of buyers.95 His principal patrons included William Graham, a merchant and cotton manufacturer from Glasgow turned member of Parliament; the Liverpool shipping magnate and self-made man, Frederick Richard Leyland; and George Rae, a banker and stockbroker, who had authored a popular handbook for country bank managers under the pen-name Thomas Bullion.96 James Leathart, a Newcastle lead merchant; William A. Turner, a Manchester manufacturer; calico printer Frederick W. Craven, also from Manchester; William Coltart, a Liverpool iron merchant; and Thomas Edward Plint, a stockbroker from Leeds, also made important purchases from the artist.97

It is perhaps not surprising that, as Dianne Sachko Macleod has suggested, many of Rossetti’s patrons approached the commissioning of artworks in a very transactional manner. It was not unusual for the artist to receive requests for paintings of a particular size or color, for example, suggesting that his patrons appreciated his artworks in much the same manner as wallpaper, drapes, or a piece of furniture.98 Yet Rossetti consistently showed himself to be a worthy opponent in these negotiations. He drove a hard bargain, and his business-world patrons respected him all the more for it.99 Compared to his younger self, this more mature, aesthetic Rossetti was far more comfortable with the knotty entanglements of art and money. Powdered gold shell, gold leaf, and other costly pigments no longer represented a financial sacrifice for the artist. In fact, Rossetti showed very little interest in painting anything unlikely to turn a profit.100

It was not only Rossetti’s personal financial circumstances and relationship to money that had changed. Already dominant at mid-century, gold’s monetary associations extended over larger and larger parts of the globe, increasingly acquiring an air of inevitability in the process. In 1873, the year Rossetti returned to his unfinished Sancta Lilias, France, the United States, and Germany adopted the gold standard, joining Britain and other primarily Western industrialized countries in a vast gold-based trading network.101 With further discoveries in New Zealand and Western Canada, worldwide gold production remained high throughout the 1860s and ’70s, with the British Empire now controlling over forty percent of the world’s supply.102 In the words of financial journalist Walter Bagehot, London’s money market was “by far the greatest combination of economical power and economical delicacy the world has ever seen.”103 Meanwhile, despite Ruskin’s calls for self-restraint, decorative and industrial artists continued to expand gilding’s reach. The metal’s glimmer was visible virtually everywhere, according to George E. Gee, the author of The Practical Gold-Worker. “[A]lmost every article, both in business enterprise and domestic life,” he noted, “is beautified and enriched by its application at the hands of studious and skillful artisans. Even the paper upon our walls, our china, tea-trays, book-edges, and covers, signboards, sewing machines, and in fact, almost every article and trinket of our household, is decorated more or less with this metal.”104

Rossetti’s Sancta Lilias was just as likely to evoke the appearance of one of these household decorative commodities as it was an early Italian painting or Byzantine icon. More immediately, the format and composition of the salvaged head recalled Rossetti’s so-called Venetian beauties of the 1860s, which show models in shallow, over-packed spaces crammed with luxurious, often gilt, accessories. Lady Lilith (1866–68) provides an especially striking example of how Rossetti’s paintings often replicated the visual trappings of the capitalist marketplace, all the while attempting to lay claim to an incommensurable, purely aesthetic form of value (fig. 20).105 In fact, as the artist himself was keenly aware, the inclusion of decorative, ideally reflective accessories increased the likelihood of his paintings finding a buyer. Seeking to entice Leyland into buying Lady Lilith, Rossetti specifically highlighted in his letter to the shipping magnate how the yet untitled painting of “a lady combing her hair” would “be full of material.”106 To his studio assistant, the artist was more transparent, requesting, on one occasion, that one of his paintings be sent to him so he could add “some accessories . . . which would make it much more attractive and saleable.”107 Besides offering viewers highly seductive visual representations of expensive commodities, his paintings also functioned as costly luxuries in their own right. In fact, these two aspects of his paintings directly built off one another.

The comparison with Sancta Lilias is instructive. Here, the gilding stands in for the valuable, often gilt “accessories” Rossetti would normally have included in the background. The frame’s wide filigreed flats and visible joints enhance the image’s planar, decorative aspect, giving the two-dimensional artwork an unusually object-like appearance (fig. 21). It is hard to imagine Rae or Leyland ever purchasing a painting wherein traditional measures of the artist’s skill and aesthetic value are so meager and the connections between art and economic value so poorly dissimulated. Condemnations of luxury remained common in the Victorian era. Following Mill and other mainstream political economists, however, Rossetti’s patrons likely viewed the consumption of luxury items in positive terms, as an effective means of boosting the economy, enhancing the nation’s material progress, and employing its workers.108 But by swapping skillfully rendered luxury objects for gold, the medium of money itself, Sancta Lilias operated in another, less secure register.

Rossetti initially promised to sell Sancta Lilias to his art agent, Charles August Howell, but rescinded the deal when the Liberal statesman William Francis Cowper-Temple and his wife came in with a more generous offer and swifter promise of payment.109 Not being industrialists, merchants, or financiers, the Cowper-Temples were very much in the minority among Rossetti’s patrons. The artist regarded them as more enlightened and spiritual in their tastes than the average collector of his paintings.110 Put otherwise, there was little pressure on Rossetti to produce a highly accessorized, more patently “valuable” artwork.

This is not to suggest, however, that Sancta Lilias was an uncomplicated embodiment of economic value, quickly redeemable in cash. Rossetti’s engagement with gold’s economic and monetary associations only imperfectly aligned itself with the goldbug logic of the times. The painting’s juxtaposition of non-metallic yellow paint—as used, for instance, in the depiction of the “gold” iris in the damsel’s hand, her gauzy dress, and the stars that crown her head—and gilding confounds the distinction between the thing itself and its sign. Their proximity suggests an equivalence between the two, which is never fully resolved, highlighting the parallels between art and money as systems of representation based on commensuration and exchange.111 Simultaneously reflective and reflexive, Sancta Lilias opens the possibility of a more critical and nuanced engagement with the representational conventions of everyday economic life and the theorizations of value that structured them.

Epilogue: Reframing Victorian Avant-Garde Art

Earlier in this article, I described Rossetti’s gilt paintings as involving “a migration of gold from the frame onto the canvas.” That is not entirely accurate, of course. Rossetti did not offset the use of gold on the canvas by an equivalent reduction of gilding at its edges. In fact, as we know, the artist devoted extraordinary attention, not to mention money, to the design and manufacturing of his frames. The artist’s decision to exhibit The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Ecce Ancilla Domini! in costly, custom-made medievalizing frames aligned with his other, similarly anti-utilitarian economic decisions, like the purchase of pricy pigments, where the conspicuous expenditure of financial resources made it possible for viewers to imagine new forms of value.112

Moreover, frames were, and arguably remain, that aspect of painting most directly connected with questions of value.113 For as Rossetti and his contemporaries understood, how a painting was framed often had a significant impact on the public’s perception of its worth. Upon learning, for example, that Frederic Leighton’s Syracusan Bride Leading Wild Beasts to the Temple of Diana (1866), a painting he judged “really bad even of its own kind,” had fetched an astronomical £2,677 at auction, Rossetti remarked to Ford Madox Brown, “I believe that flush frame [the artist] put on it did the job!”114 In short, for an artist to apply him- or herself to the design or making of frames was, by definition, to become involved in the most explicitly economic aspects of painting.

Lastly, frames were also where the painter often affixed inscriptions, further elaborating on the artwork’s subject matter. The Girlhood of Mary Virgin’s original frame included two sonnets Rossetti had written, the first explaining the “general purport of the work” and the second “its individual symbols.”115 Likewise, it is generally believed that Ecce Ancilla Domini! originally bore a frame with “Latin mottoes.”116 Frames were thus where the painter-poet brought visual and textual modes of signification most directly into conversation. Inviting viewers to compare and contrast the two modes of meaning-making, they functioned, like the money changer’s scale, as instruments of commensuration and exchange.

It cannot be a coincidence that, among all nineteenth-century schools, it was British Pre-Raphaelitism and the Aesthetic Movement that showed the greatest interest in frames. The simple, day-to-day experience of making art in the land of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, and William Stanley Jevons—“a nation of shopkeepers,” known for its essentially inartistic temperament—would have predisposed these artists toward engaging in these unusually abstract debates concerning the nature and source of economic value, the material mediums through which value circulates, and the roles economic and artistic representations played in the constitution of society as such. Working in tandem, Rossetti’s gilt frames and gold-laden canvases directed viewers’ attention away from the simple representation of meaning to the economic and social context in which art was made and consumed: Who gets to define value, whether aesthetic or economic? What makes something valuable, and how do these standards structure society and its dominant modes of visualization?

That Rossetti’s and Ruskin’s answers to these questions did not align is notable. According to Tim Barringer, the critic’s original 1851 intervention on behalf of the group “at a stroke, transformed the terms of critical debate about Pre-Raphaelitism from a focus on the religious implications of a revival of ‘early Christian’ art to an overriding concern with the process and the value of painstaking, laborious representation.”117 By ignoring, however, that aspect of Rossetti’s paintings that, superficially at least, most conspicuously recalled the art of the past, Ruskin failed to engage with what, ironically, most made the artworks modern: the artist’s attempts to reimagine the material foundations of British society and the abstract standards of value that shaped them. Ruskin’s carefully ordered, hierarchical social body, built on reciprocal self-sacrifice, left little room for these more modest counter-economies of light and luster orchestrated by artists and workers on their own behalf.

“In capitalist society,” T. J. Clark observes, “economic representations are the matrix around which all others are organized.” For Clark, this meant an art history that paid close attention to class. “[O]nly think of the history of bourgeois costume, or the various ways in which the logical structure of market economics came to dominate the accounts on offer of the self and others,” he continues.118 In looking at gold and gilding in Victorian avant-garde art, my intention has been to shed light on a different kind of intersection between art and economics, one that has yet to be fully integrated into interpretations of the intertwined development of modernity and modernism centered on the art of nineteenth-century France. Not unlike the mainstream political economists whose theories of value they sought to challenge, what mattered most to Rossetti and Ruskin was not the surface phenomena of capitalist society but its inner, abstract standards and structures.

Notes

Acknowledgments: This article stems from a paper I originally delivered at the Color and Materiality symposium at Penn State University in October 2018, the topic of which originally came to me about three years earlier while walking through the galleries of the Tate Britain. I’m thankful to the organizers of the event, Sarah K. Rich and Daniel M. Zolli, for providing me with an opportunity to present my initial thoughts on the topic of gold and gilding in British avant-garde art. As my ideas on gold and Pre-Raphaelite art developed, I took advantage of opportunities to present my research at the annual meeting of the College Art Association in February 2021 and the Towards a Modern History of Color symposium hosted by Pembroke College, Cambridge University in June of the same year. I owe a particular debt of gratitude to Tim Barringer for his initial encouragement and to Kirsty Dootson for her timely pandemic-era research assistance and always illuminating insights. I also wish to express my deepest gratitude to Tara Contractor, whose excellent dissertation, “British Gilt: Gold in Painting from Blake to Whistler” (PhD diss., Yale University, 2022), I only became aware of once well into the project. Contractor graciously shared the most relevant chapters of her dissertation with me in July 2023, as I began working on this article in earnest. Exploring the overlap between Pre-Raphaelite gilding, new electroplating technologies, and the Victorian manuscript illumination revival, Contractor convincingly shows how artists in the group “embrace[d] a feminized approach to gold that distanced them from the metal’s associations with the masculine-coded spheres of industry and empire.” Our arguments thus fundamentally diverge. [An abstract and other bibliographic information about Contractor’s dissertation are available online: Tara Contractor, “British Gilt: Gold in British Painting from Blake to Whistler” (PhD diss., Yale University, 2022), accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.proquest.com/pqdtglobal/docview/2699718122/D4191FC4DE984176PQ/1?sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.] I acknowledge, however, that there are overlaps in our research both in terms of source materials and general lines of inquiry. Finally, I want to thank the anonymous reader for nonsite.org for their feedback, which helped me to solidify my argument and improve the coherence of the text, as well as the editors, Bridget Alsdorf and Marnin Young, for their invitation to contribute to this special issue and gold-star patience, as I scrambled to get image files and put the final touches on the text.Once omnipresent in Western art, where it served to underline both the otherworldly character of religious subjects and the material wealth of artworks’ sponsors, gold almost entirely disappeared from painted panels and canvases by the sixteenth century. Outlined in convincing detail in Michael Baxandall’s classic Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (1972), the historical context and contours of this transition are today well-established.1 More than simply old-fashioned, the presence of gold and other precious, typically lustrous, materials came to be seen by makers and theorists of art as undermining the very definition of painting and what it meant, more generally, to be an artist.2

Laying the foundations for what would become a customary distinction between aesthetic and economic value, Leon Battista Alberti, writing in the fifteenth century, sharply distinguished the pleasures of art from those of property. Unlike a piece of expensive jewelry or the miser’s gold coin, the ideal work of art transfixed viewers through its skillful, illusionistic deployment of line and color. “[T]here are those who utilize gold in a disproportionate way because they think that gold lends a certain majesty to the historia. I do not approve of them at all. Indeed, if I would like to paint Virgil’s Dido with a golden quiver, [who] kept [her] hair in a knot with a golden clasp, [for] whom a golden band girded [her] dress, and who rode with golden reins, and, in general, all things shone because of the gold, I [would] strive, nevertheless, to imitate by means of colors rather than means of gold that abundance of golden rays that strikes observers’ eyes from every part,” Alberti contended.3 In fact, theorists and collectors would increasingly come to see the ability to imitate precious metals—gold especially—using ordinary, non-metallic pigments as a measure of an artist’s skill. Persistence in using gold and other expensive, eye-catching materials became, meanwhile, the mark of painters seeking to cover up deficiencies in their design or, worse, willingly abandoning what they knew to be true and good to cater to the untutored tastes of patrons.4