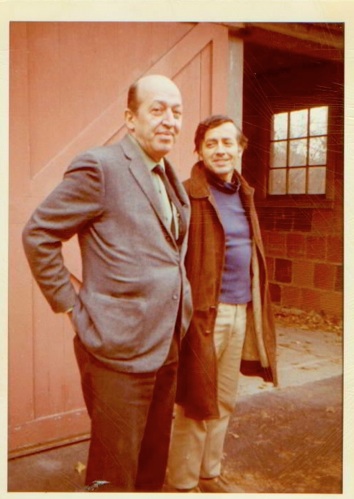

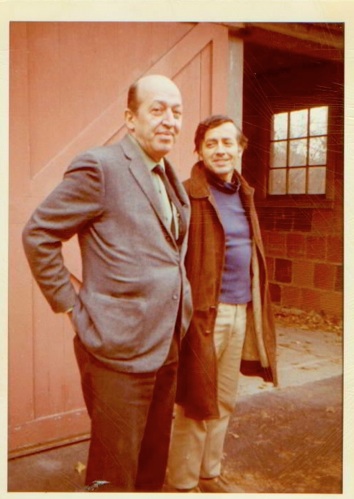

It was Marilyn Morgan who suggested that her husband, the abstract painter Friedel Dzubas, appear in person at the offices of Partisan Review to answer the following classified ad: “PR CONTRIBUTOR and 13 year old son wish rooms for five weeks, beginning July, in country near swimming, other children. Clement Greenberg. Partisan Review, 1545 Broadway, NYC 19.”1 This was June 1948. Other contributors had placed ads—there is one from Mary McCarthy soliciting a “comfortable, small house”—but Dzubas and his second wife understood what meeting the major art critic of his time might hold for a younger artist. Despite Dzubas’s frequent claim that he had no idea he would be meeting Greenberg, the ad clearly posted the contributor’s name and the artist knew full well what he was about. And from the first, Dzubas and Greenberg liked each other. The artist’s opening gambit, delivered with charm and bravado, assured a mutual understanding: “‘Here I’ve been reading your stuff for the last… four or five years and I never could make head or tail out of it, but the main reason that I buy the stuff is because I can’t make head or tail of what you’re writing there,’ and we started to joke around.” So with his son, Danny, Greenberg moved into the guest quarters of Dzubas’s sixteen-acre, seventy-eight-dollar-a-month sublet in Redding, Connecticut for the summer. “Ya, he loved, he liked the, liked the house, liked the whole situation. Liked me. I liked him, too.”2

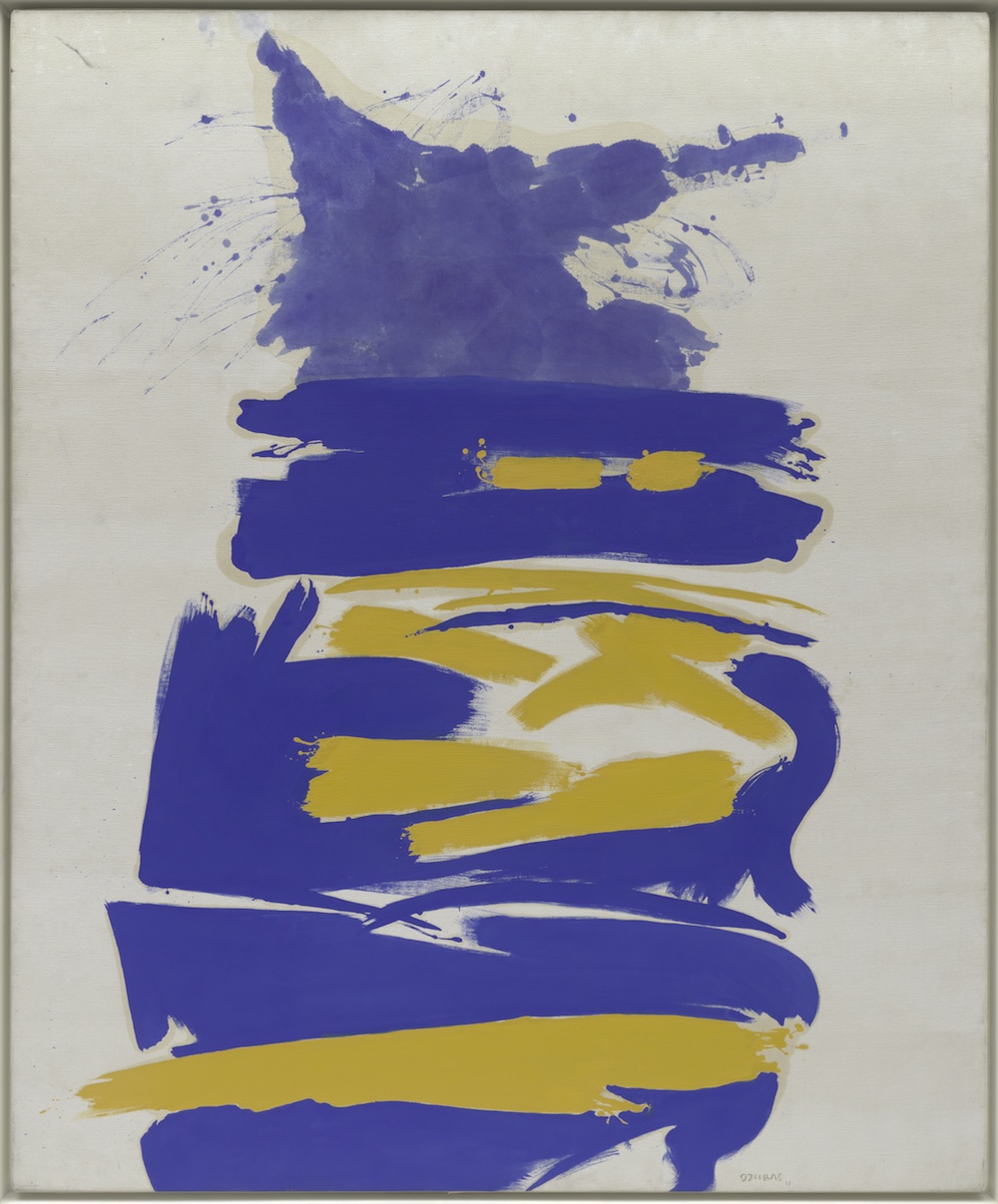

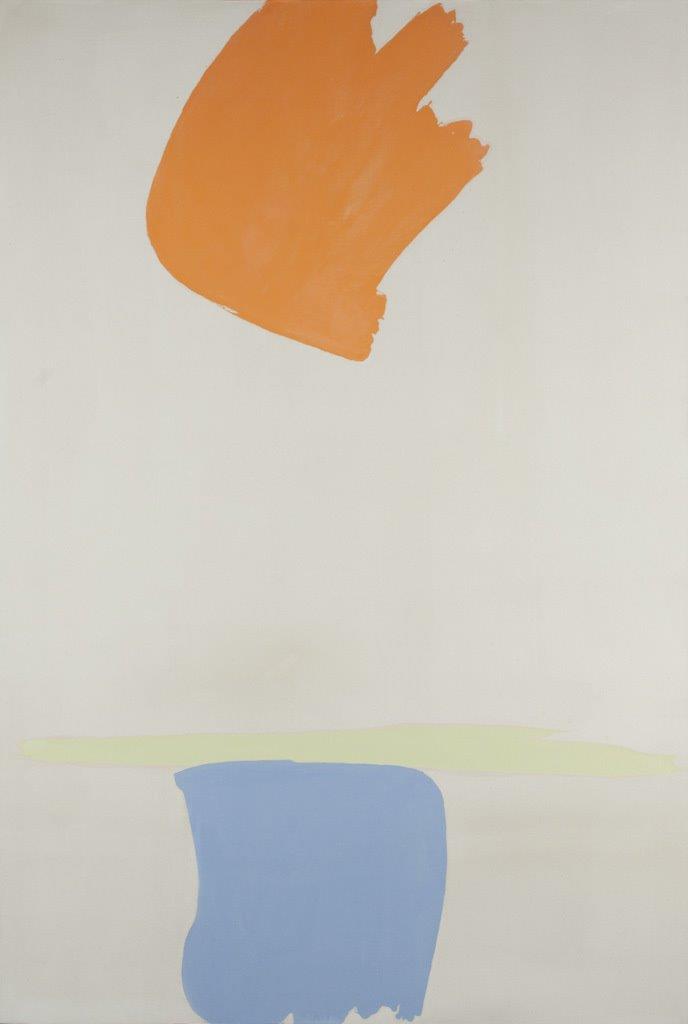

Thirty years on, in 1977, Greenberg agreed to write an essay—until now seemingly overlooked in the literature on Dzubas3—for a small retrospective, “Friedel Dzubas: Gemälde,” at the Kunsthalle Bielefeld.4 At less than a thousand words, the essay is important, not least because it addresses the career of a significant painter, one whom Greenberg included first in “Talent 1950,” an exhibition of younger artists at the Kootz Gallery (co-curated with Meyer Schapiro), and again almost fifteen years later in his 1964 exhibition, “Post Painterly Abstraction.”5 The decade-by-decade review at once summarizes Dzubas’s artistic practice up to the 1970s and casts retrospective light upon Greenberg’s 1964 accounting of the new art.6 By turns sympathetic and severe, Greenberg portrays an artist who in his estimation had yet to realize his full potential. For Dzubas, Greenberg’s opinion was unsurprising: in a letter to Dzubas accompanying the essay, Greenberg wrote with characteristic candor, “[The essay] wasn’t at all hard to write, I think because I permitted myself complete frankness & repeated things I’d already told you.”7 Greenberg’s overall tone in the essay is encouraging, if cautious: even as he reflects on his own preference for Dzubas’s early “painterly abstractions” in watercolor, he finds a Dzubas 1960s “linear” canvas at the Guggenheim “one of the best postwar items that the museum owns” (fig. 1). The key statement comes in the third paragraph and is directed to the artist, who, Greenberg insists, has yet “[to] enter […] the Promised Land with great, not just good, paintings.” Here he acknowledges Dzubas’s early originality while cleaving to the possibility that the day of major achievement will come. As he vouchsafes in the letter, “(It was written from the heart).”8 The point here is that for Greenberg to write this sort of essay was altogether unusual, an act of friendship on those grounds alone.9

Dzubas’s history is complex. He was born in Berlin in 1915, the child of a Jewish father and Catholic mother. As an adolescent during the rise of National Socialism in Germany, Dzubas (originally Dzubasz) suffered under the restrictions of Mischling status defined by Nazi race laws, which categorized such children as “mixed race.”10 A Mischling of the first degree or half Jew (Dzubas’s paternal grandparents were full Jews), Dzubas was forced to cope with the vagaries of emotional, professional, and political marginalization in pre-war Germany. Like many middle-class Jewish families at this time, the Dzubaszes—among them artists, book artisans, and graphic designers, textile managers, and translators—were politically left leaning. They identified primarily with the communists, although they were members of the official Jewish Community.11 Their anti-fascist/pro-Stalinist activities, such as attending meetings and printing and distributing pamphlets for communist-affiliated organizations, added tension to the already fraught social vagaries affecting their citizenship-status in the German Reich.12 Dzubas’s artistic training came fitfully, as anti-Semitic actions became more and more overt during the years 1931 to 1933, insinuating resistance to school and job opportunities for young people with Jewish blood that culminated in the Nuremberg Laws of September 12, 1935. When recognized as having Jewish blood, certain teachers and peers at various primary, secondary, and post-secondary educational institutions ostracized Mischlinge, although their legal status was not yet threatened. Opportunities for professional training were also circumscribed in the run-up to the National Socialist Machtergreifung on January 30, 1933.13 This fact alone precluded extended study with Paul Klee who would be dismissed from the Bauhaus at its dissolution in 1933. Whether Dzubas actually attended the Akademie der Künste in Berlin—a claim Dzubas made—cannot be confirmed by existing documentation.14

Like many young people who graduated from an Oberrealschule (high school)—as opposed to a Gymnasium from which students could expect to move on to university—Dzubas was apprenticed, in his case to a decorative painting firm, the M. J. Bodenstein Wohnungs-und Dekorationsmaler.15 There he was schooled in the art of fresco and other techniques related to wall decoration. Dzubas may have learned graphic arts and book design, skills he would depend on in his early years in America, from his uncle Wilhelm Dzubas, a respected graphic designer and decorative painter in Berlin16 and from another uncle, Hermann Dzubas, who owned a Buchdruckerei in Berlin that had published Die Rote Fahne, a communist newspaper.17

The systematic persecution of Volljuden and Mischlinge put in place by the Nuremberg Racial Laws in 1935 catalyzed the hurried formation of Jewish Youth Agricultural Training Camps, the expressed aim of which was to obtain visas to the United States, Palestine, or South America.18 Between 1936 and 1938, Dzubas trained at one of the few non-Zionist youth training camps, in Gross-Breesen, Silesia.19 It was through this program that Dzubas finally emigrated—as a farmer—to the United States in 1939 at the age of twenty-four, using in addition to his given name the Americanized “Frank Durban.” He was among the first trainee émigrés to enter Hyde Park Farmlands in Burkeville, Virginia, a settlement formed in the United States explicitly for the purpose of receiving trainees from Gross-Breesen. Here he remained with his German wife, Dorothea Brasch, for his first seven months in the United States; he left the settlement for New York City in May 1940.20

In less than a year, after several freelance jobs in graphic design—while bussing tables or making food deliveries—a chance meeting with William B. Ziff, Chairman of Ziff Publishing Company, resulted in a full-time position at the Ziff publishing house in Chicago, where for the next four years he worked as a commercial artist leading a book design team. Dzubas fell in with “a very aware, very sharp intellectual group of writers in Chicago, and I got very close to them and they were very well informed [in] thought, politics, literature, etc. Also art.” It was through this group that Dzubas began reading the Trotskyist New York intellectuals who wrote for the Partisan Review. At the same time, Dzubas was working in watercolor and had been accepted into several “Annuals” under the aegis of the Art Institute of Chicago.21 Returning to New York late in 1945, he engaged marginally with artists painting in the Abstract Expressionist style. By 1948, Dzubas had entered into a productive personal and professional relationship with Katherine S. Dreier, contributing his graphic services and art to her organization, Société Anonyme, and had in effect launched his artistic career in New York by befriending Clement Greenberg that same year at the offices of Partisan Review.22

So what did Greenberg actually say about the work? It’s important to understand that for the greater part of thirty years, Greenberg believed in this artist. But by 1977, his claim was that Dzubas had yet to construct a solid foundation for his future artistic development; that he had failed to “follow up on his achievements and achievedness”; that, instead, he had “let it all lie scattered.”23 Greenberg felt Dzubas had not yet done what would have been necessary—had in a sense refused to bear down on, to dig deeper into a clear artistic identity. This is what perplexed the critics and what earlier in his career had provoked the English art dealer John Kasmin’s exasperation: “You’re here, you’re there…. And it’s difficult for us to cultivate a certain taste if it seems that jumpy.”24 Dzubas’s seeming inconsistencies in approach—his shifts from expressionistic cursive gestures in the 1950s, to clean-edged, lucid color shapes against large areas of active white space in the 1960s, and on to loose, dynamically-arrayed color blocks in the 1970s—ultimately prompted Greenberg to aver that Dzubas’s art was indeed original, but this originality was somehow “surreptitious.” Dzubas had “fooled everybody, including myself as well as such a good critic as Michael Fried.” What he meant, of course, was that over the years, Dzubas had allowed himself to be seen as a less impressive painter than was in fact the case.25

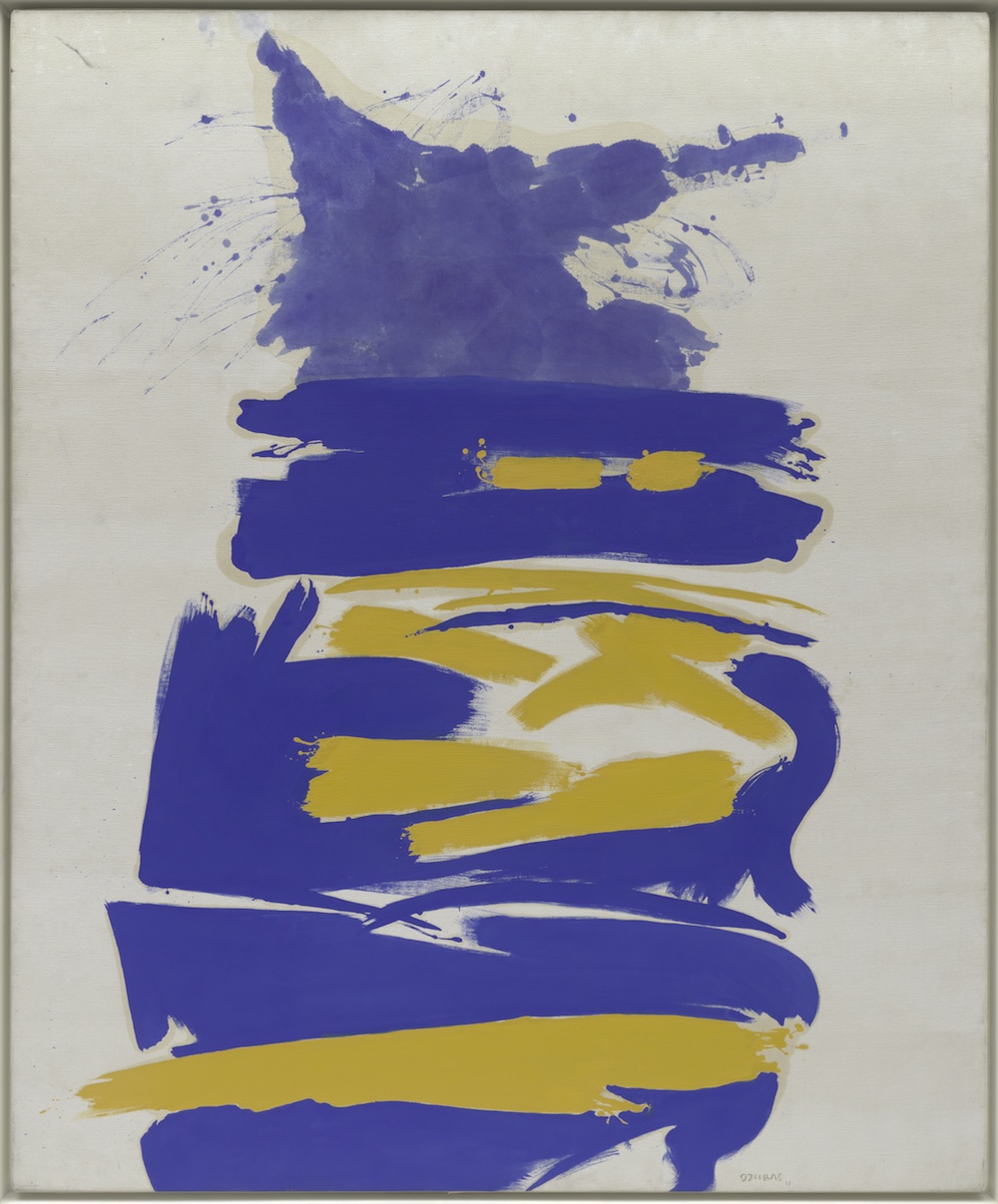

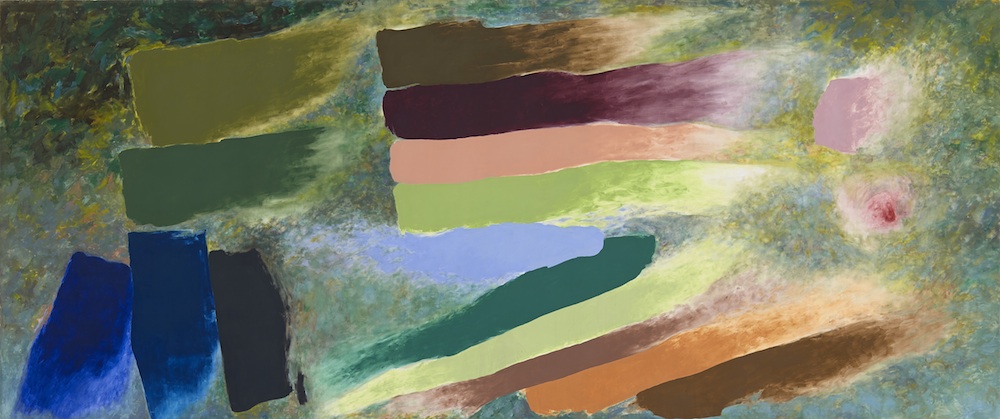

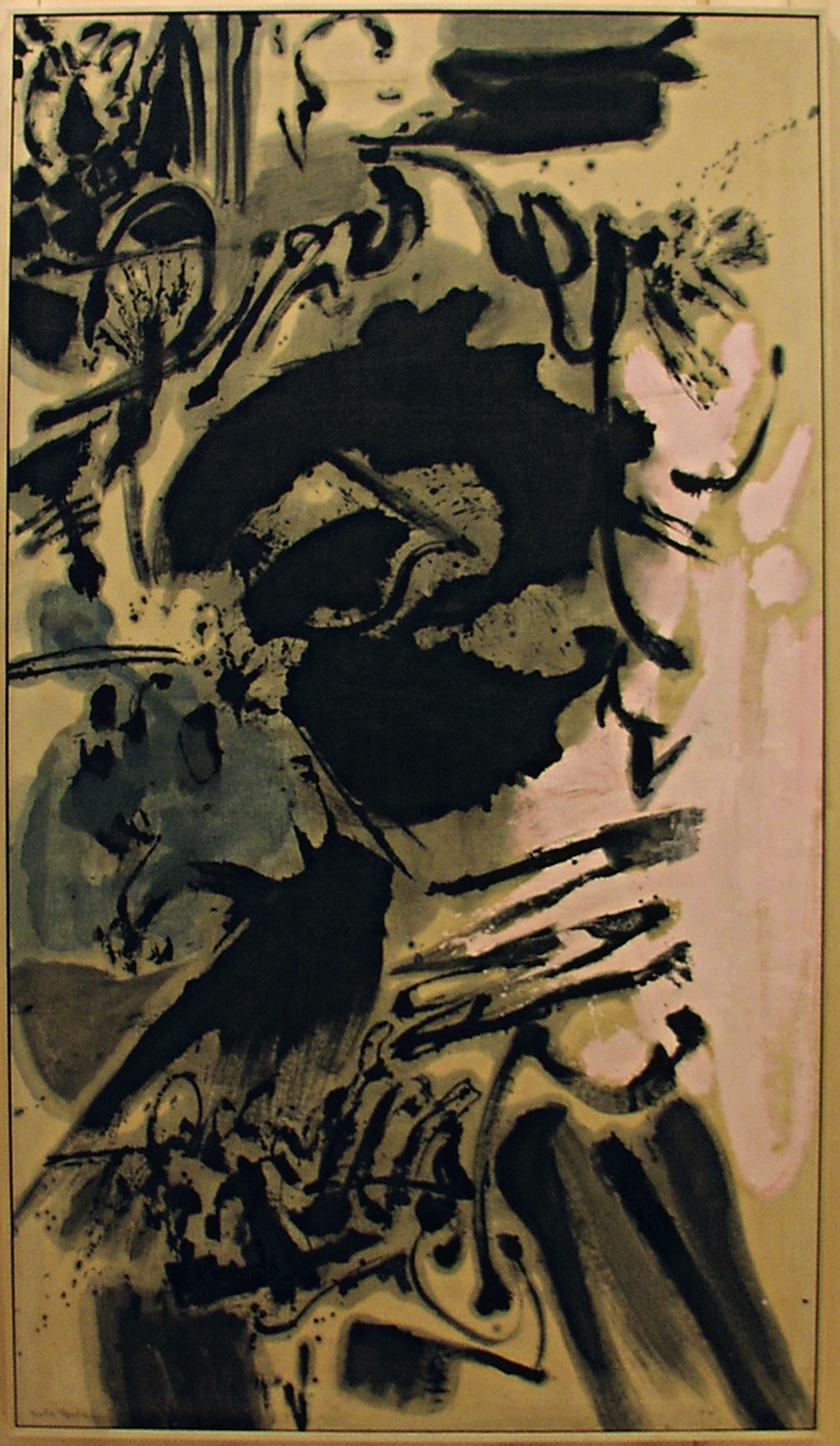

In eight paragraphs, the narration goes like this. As an Abstract Expressionist painter in the 1950s, Dzubas was poised to “become one of its masters, a junior one, but a master nonetheless.” Greenberg points to Dzubas’s 1955 [sic] painting in the Whitney Museum collection, Yesterday, (1957; fig. 2), a large (44 ½ by 108 ¾ in.) horizontal abstract, as evidence, comparing it favorably to the museum’s Pollock and their “de Koonings and Kline.”26 Immediately, however, he gets to the crux of the problem as he sees it—Dzubas’s tendency to compose his canvases, to “fasten […] down all four corners,”27 to fill up spaces rather than leave them open, to, in effect, preclude the “indeterminate spaciousness” that the critic valued at that time.28 Yet Dzubas finally stepped beyond these self-limiting mannerisms when, in the 1970s, he combined his 1960s linear style with what Greenberg called a malerisch or painterly tendency.29 (See fig. 3.)

Greenberg had suggested that such a synthesis originated within the practices of painterly abstraction, the idea being such a revision was effected through a fusion of “clarity and openness.”30 Exemplary in this regard were works by artists “like Still, Newman, Rothko…” et al.31 Dzubas extended these artists’ revisions by using contrasting “instrumental qualities”—thinned paint surfaces and bare areas of canvas as against “the density and compactness” of Abstract Expressionism—thereby achieving the “freshness” characteristic of the new art.32

Greenberg looked beyond the context of Cubism to Venetian art for the soil in which “painterliness” had taken root: “The painterliness itself derived from a tradition of form going back to the Venetians. Abstract Expressionism—or Painterly Abstraction, as I prefer to call it—was very much art, and rooted in the past of art.”33 In describing Dzubas’s melding of old and new, then, Greenberg might have drawn on this very notion, for Dzubas was in thrall to fresco mural painting, not only by Giotto, but also by Titian and Giambattista Tiepolo, in particular the latter’s frescos created for the Residenz at Würzberg. Frank Stella took up the notion that Dzubas folded his early training as a Dekorationsmaler into his painterly vision when he wrote, “Early watercolors, decorative house painting, and commercial illustration all came together for him.”34 Like Greenberg, Stella understood that the foundation of Dzubas’s style lay in the artist’s early training and apprenticeship in wall painting and graphic design, which he expressed in his pictorial responses to the rhythmic disposition of massed color groupings so characteristic of Venetian fresco painting.

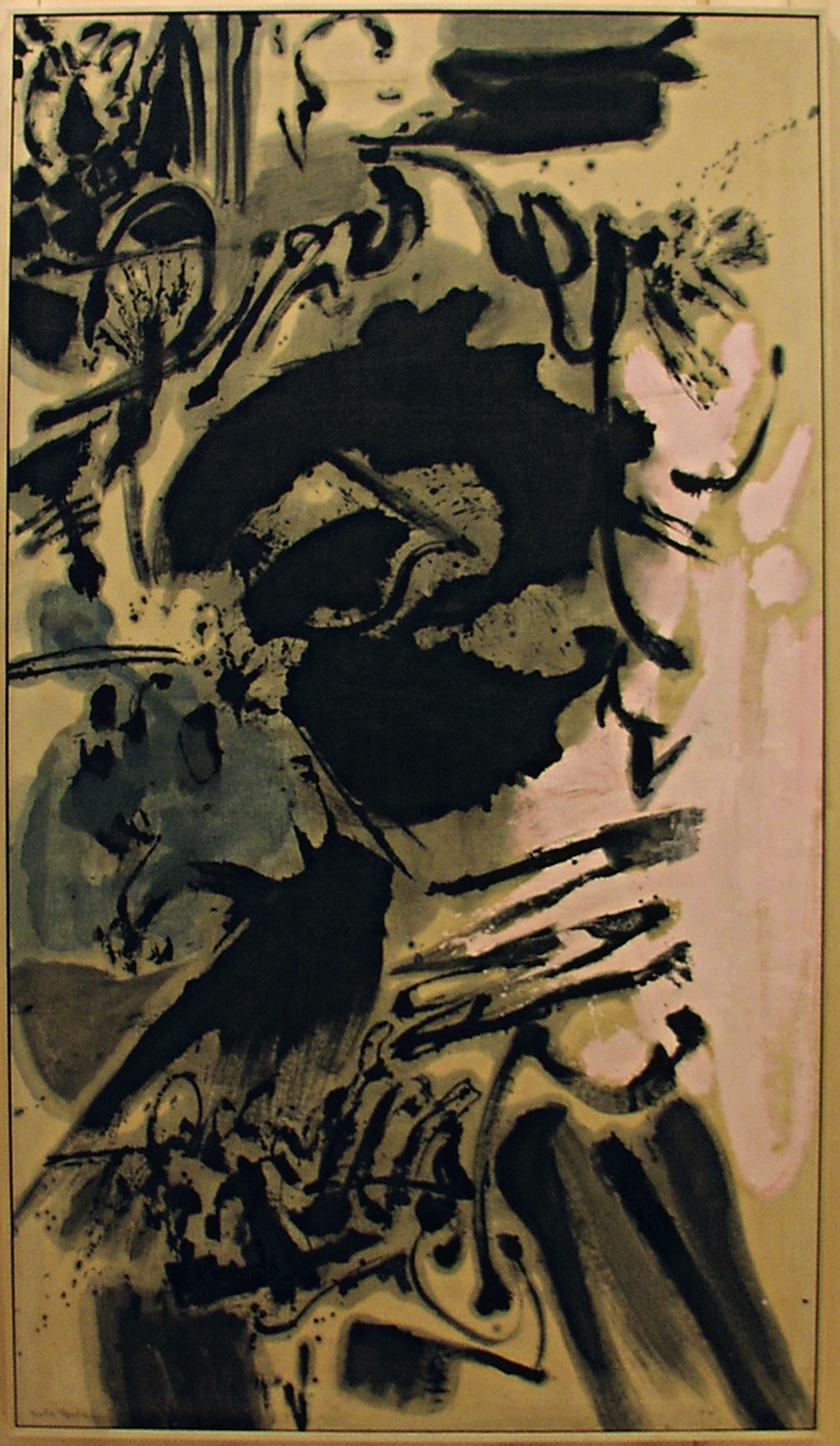

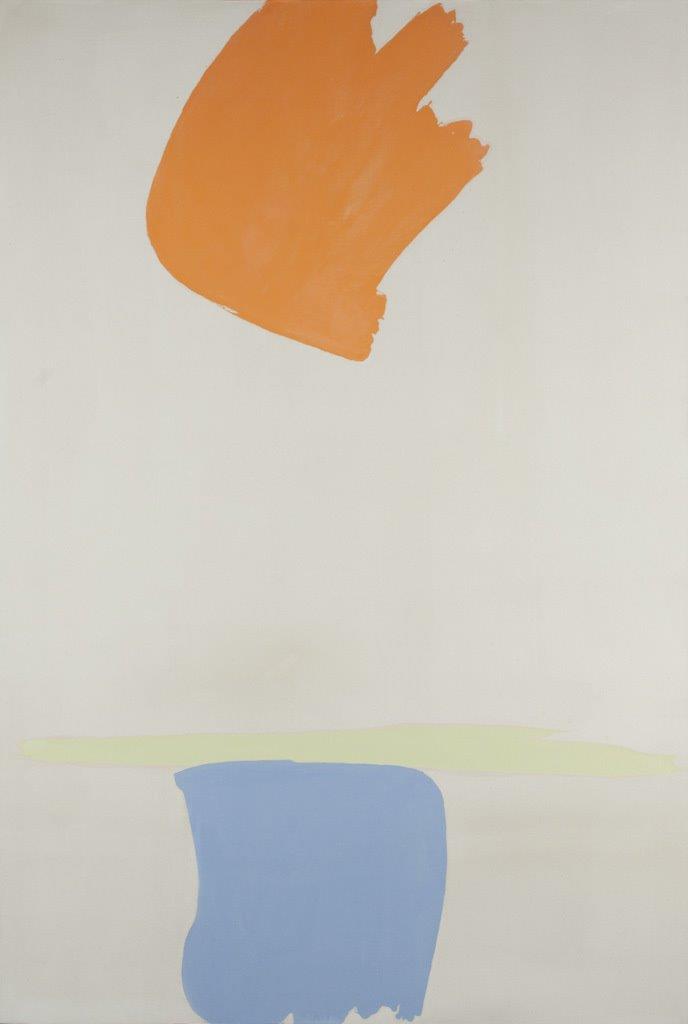

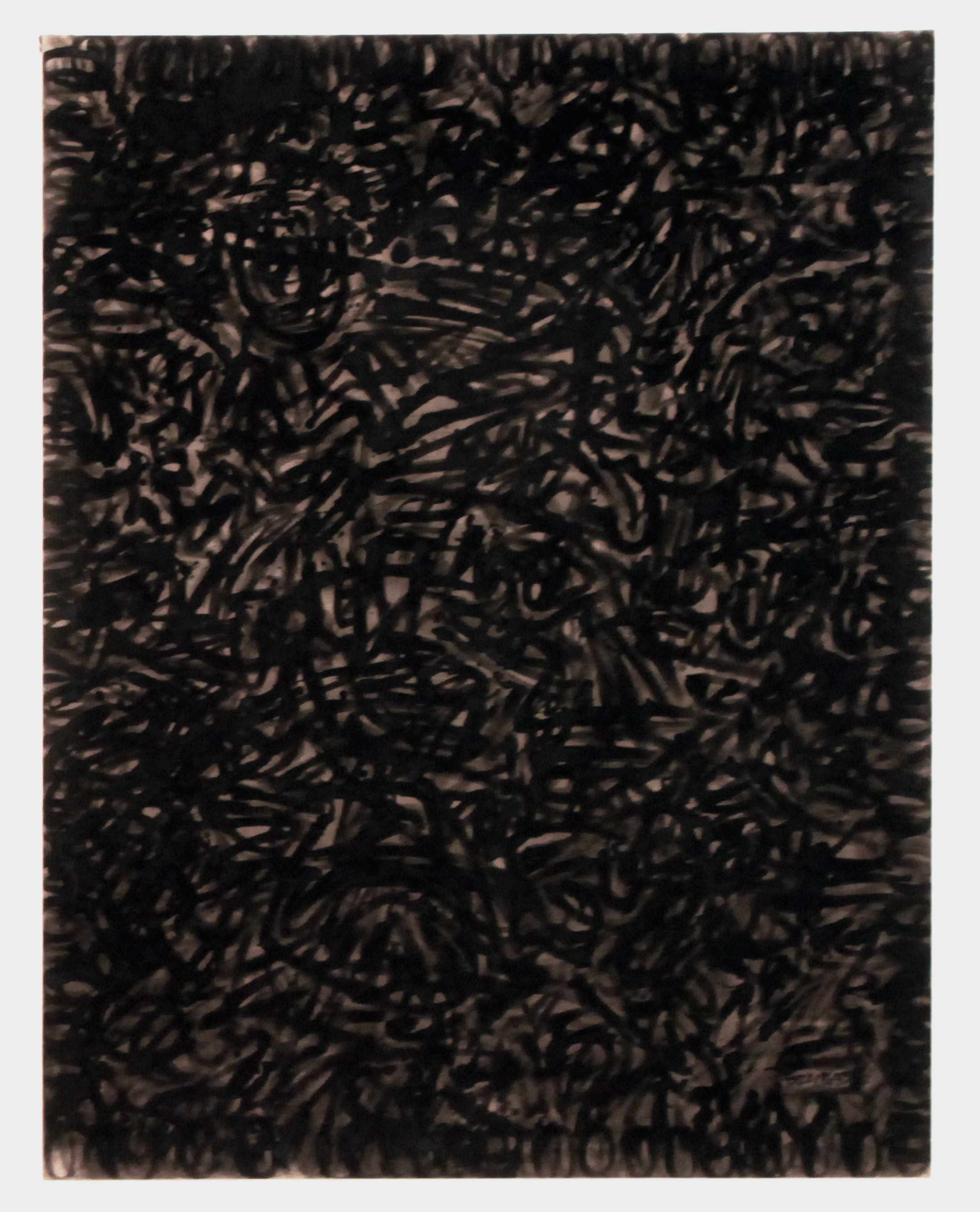

A close look at Dzubas’s surfaces is key. Dzubas did not stain his canvases. Rather, he primed them with two, sometimes three layers of gesso.35 As he clearly stated to Charles Millard in 1982, “I never stained. The only time I stained was when I was still working with oil on, on, not on canvas but on old bed sheets, you know, when I soaked the bed sheet, practically, in turpentine and then stained with cheap house paint that I had into the soaked surface.”36 (See figs. 4 and 5.) Which isn’t to say he was opposed to the method of soaking and staining. He clearly rubbed and pushed his pigments into his ground. This is obvious from the finish of his work, where the weave of the cotton duck remains exposed. But Dzubas relied for this effect on the double characteristic of liquescence and resistance in his mediums, whether watercolor, oil, or later with Magna acrylic, which he began to use in 1965. Characteristic of the opaqueness he sought in his early gouache-like watercolors from the 1940s that feature wet into wet, frankly figurative or allusive images in a loose expressionistic style (fig. 6), his later surfaces, no matter how thinly painted appear opaque even as he scrubbed his medium into the warp and weft of the fabric.37 Dzubas’s primed and gessoed canvases in the 1960s held his color shapes on the surface, pooled, controlled, and contained by their serrated or smoothed edges (fig. 7). In the 1970s, Dzubas feathered out the opaqueness, in a gesture he referred to as “fading off” or “fading out.”38 That is to say, Dzubas molds, pushes, and eases his pigments into forms that meld with, even as they resist, their material surrounds (fig. 8). This would change in the early 1980s when he directed his assistant to prime the canvas in a new way. As he told the curator Charles Millard in 1982, “Instead of priming it so it would, it will hold the turpentine on the surface and kept it on the surface for a while where I can work it. It’s primed now so meagerly that the medium immediately sucks in and you can’t, really, you can’t dance around… you have to put it down and leave it, so to speak. Whatever you put down, it it’s not open to manipulation and you’re stuck with it.”39

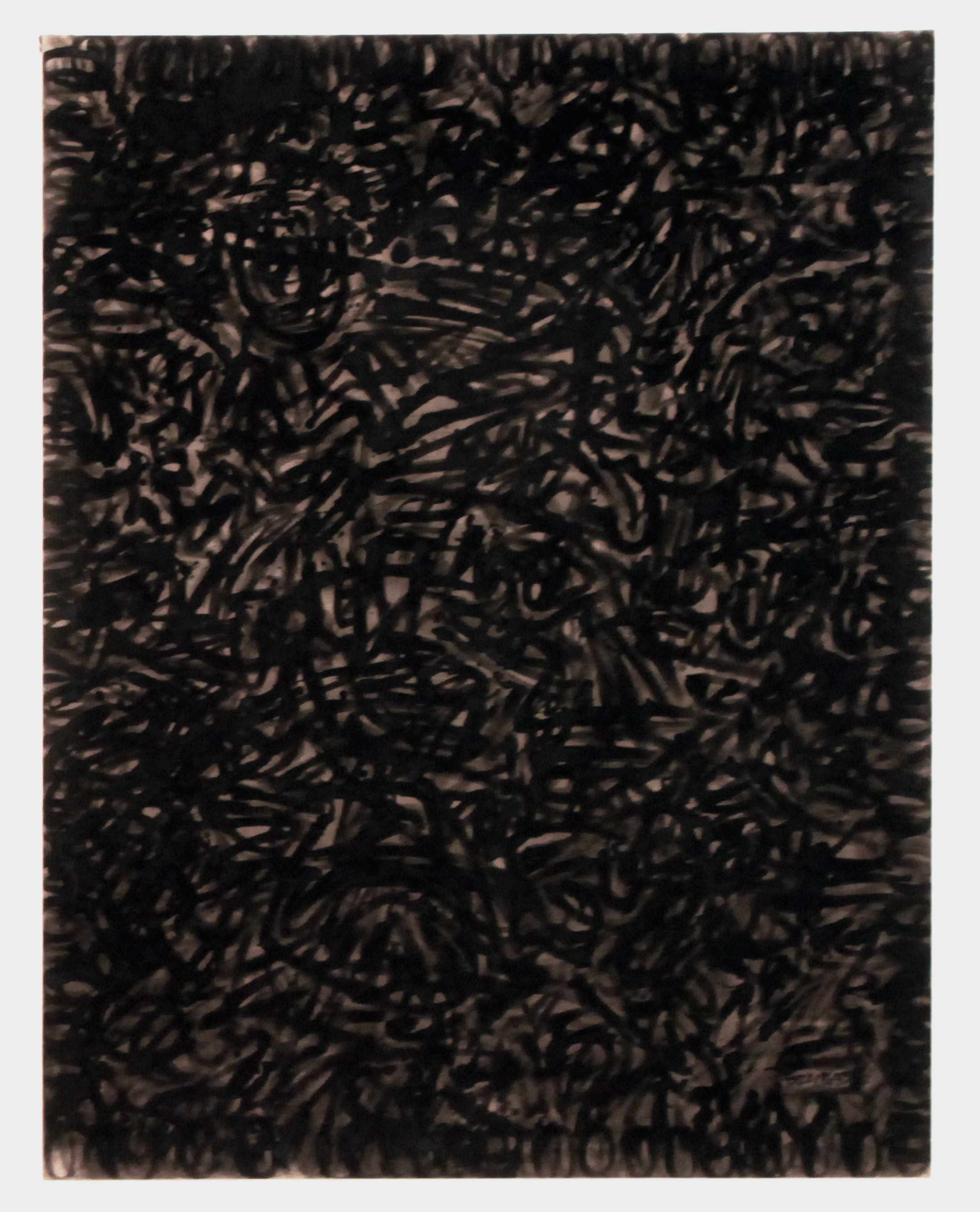

Dzubas generally divides his production into decades.40 When the artist took up oils in earnest in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he created an overall calligraphic, painterly surface with multiple foci in the spirit of Pollock’s early surrealist automatism. From gestural abstraction in the 1950s, Dzubas moved into a short-lived stylistic phase in the early 1960s, in which he filled his canvases with tightly woven, black linear markings coursing through white or off-white grounds (fig. 9).41 Paintings from the later 1960s feature close-valued hues laid out in two or more shallow fields of color, each bounded by either serrated or clean edges on an otherwise bare primed canvas, so that while color shapes nest, overlay, or touch, they are held in check by what Barbara Rose characterized as “arrested motion” or “dynamic stability.”42 “Emptying-out” the canvas, leaving a few large color areas gently abutting or in kinetic tension seemed to the artist necessary “after the indulgences and the semi-organic chaos of Abstract Expressionism.”43 Simultaneous “centers” exist within a large white space, which for Dzubas became an “essential first…. where the immaculate white, the virginity of the white, plus the strength of the white provides the strength of the whole. The untouched surface, the unedited surface was a very important active element, the way I felt things, the way I saw things.” Each color area is activated by proximity to its neighbor, the entire surface fixed within a square field. Color per se gains prominence, which Dzubas situated in dialogue with the revealed areas of white, the white acting as “the emotional element to deliver my message.”44

Dzubas’s paint medium from 1965 to the end of his life in 1994 was an early version of the first acrylic paint, Magna, developed by Sam Golden and Leonard Bocour between 1946 and 1949. Morris Louis was among the artists, who include Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Kenneth Noland, to use this experimental medium.45 What Dzubas liked about it was that it displayed the fullest saturation available at the time while holding its color when thinly applied.46 Nearly as fluid as oil paint, the resin compound added resistance. “It doesn’t let itself be pushed around that easily…it will not let itself be violated, and an additional inducement was, you never quite know what you will get…. [And it is] never quite know[ing] what you get that prevents you also from being too facile.”47 Working with hues that held and yet could be laid down in thin applications allowed Dzubas to achieve the shallow space he sought, even as he insisted on retaining evidence of the brush not only in his color shapes, but also in the dappled surrounds he would develop in the next decade.

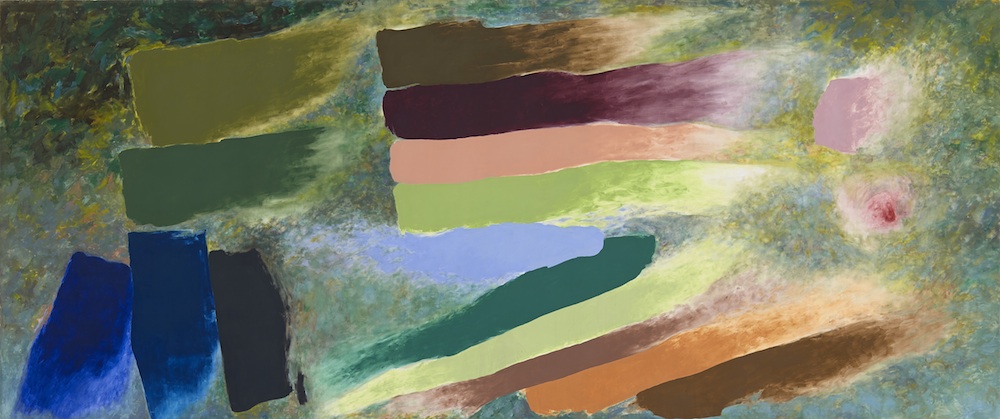

By the 1970s, Dzubas was creating overlapping or contiguous, attenuated tesserae and large, elongated rectangular shapes with rounded or modified corners using brushstrokes that left a clean edge, but for feathering generally at one end. Poised in tight relational groupings, these “phalanxes,” as curator Ken Moffett described them,48 are placed vertically, diagonally. Contrasting color groups in close values seem to thrust forward and recede in a contre-jour effect brushed in with pigment.49 Crossing (Apocolypsis cum Figuras, A. D. 1975) (1975), for example, is essentially a picture of shallow spaces that through motivic repetitions, group divisions, and directional thrusts achieves a gait simulating all-over spatial agitation, as if figures were not so much traveling across the surface as assembling for immanent action.

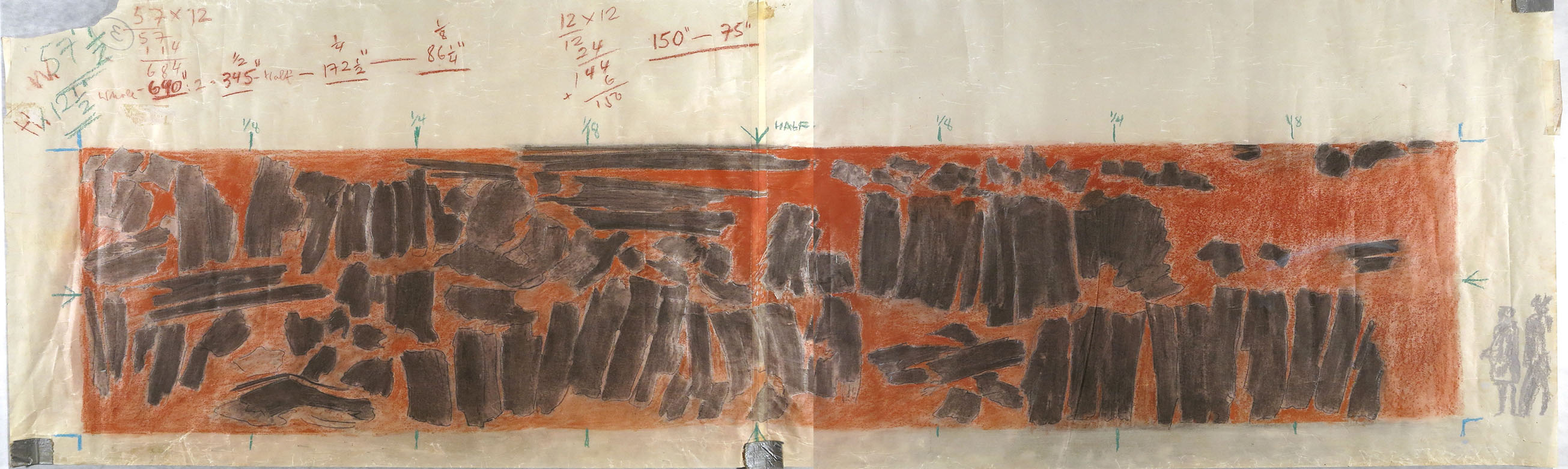

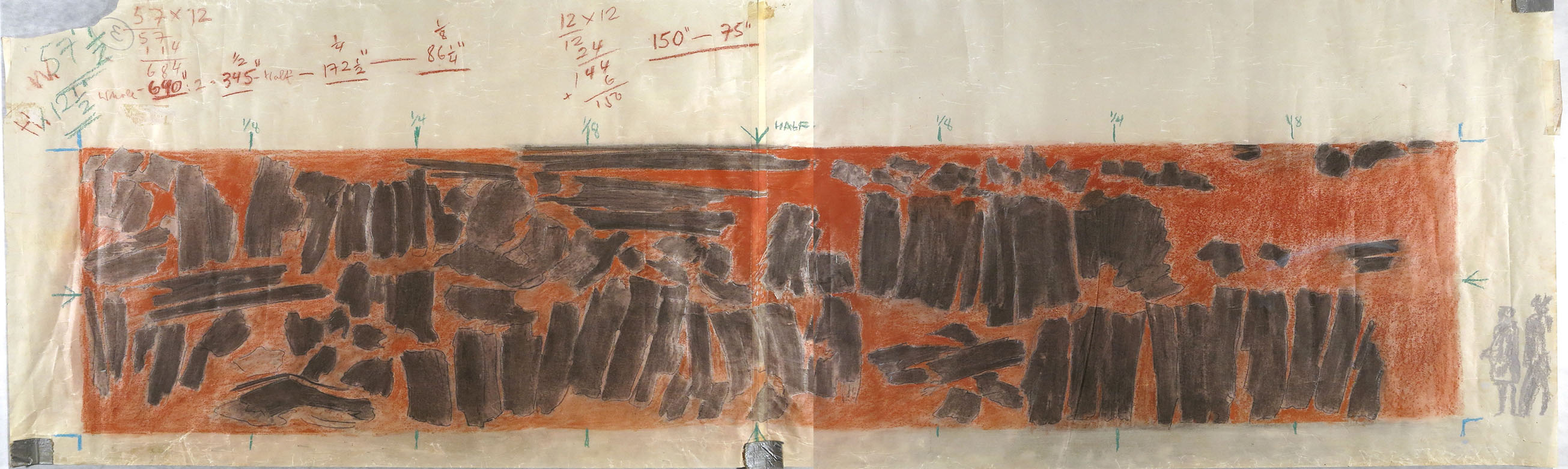

Turning to a tradition centuries old, Dzubas often worked from small sketches (or modelli)50 that he would scale up to gargantuan size. From color tests (fig. 10) to painted sketch (fig. 11), he then moved to tacking a canvas to the floor (fig. 12), applying gesso layers, and measuring and at times outlining his shapes in gesso.51 He would then prop the modello on a low easel and with paint brush in hand loosely scale up the color scheme he had previously worked out—as can be seen in a photo of the artist transferring his acrylic sketch (fig. 13). This working sequence was followed in the creation of Crossing, a painting thirteen and half feet high by fifty-seven feet across, commissioned by philanthropist Lewis P. Cabot and contracted by Joseph Henderson, president of the Artcounsel, Inc. for the Shawmut Bank in Boston.52 The process proceeds in several stages: a sheet of color tests and an acrylic sketch (fig. 14), a scale study in red crayon, charcoal, and graphite, conveying measurements used for transferring the shapes to canvas (fig. 15).53 Then a “cartoon” mock-up on which the outlined tesserae enclose numbers that correlate with the colors that would fill them, following an age-old stained-glass technique. Photographs of Dzubas at work on the painting show paint cans, brushes, oil sketch, and painted contours.54 Wes Frantz, Dzubas’s studio assistant from 1980 to 1987, viewed Dzubas at close range: “Friedel…liked the freedom to interpret both what he did and what he saw with the moment in mind. But it didn’t mean he was totally spontaneous. When I first saw his sketches that he turned into larger paintings I thought he was abandoning his motion of spontaneity, but quite the contrary. With Friedel’s painting the devil was in the details. If you compare closely a small sketch to a large painting, the large painting will have all the details that the small ones don’t. And it’s in those details that Friedel sought his identity.”55

It’s interesting that Dzubas had considered creating a fresco when the monumental Apocalypsis Cum figures/Crossing was first proposed for Shawmut Bank in 1973. He felt an affinity with master fresco painters such as Giotto and Tiepolo, with the whole of “Western tradition, rather than the visual phenomena of the last ten years in Europe and America.”56 He admitted having in mind Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel, which he had visited in the 1960s and early 1970s, claiming he wanted “to outdo Giotto… to put in everything I knew and felt, for better or for worse…. It felt right and good. A gut reaction, not intellectualization.”57 Not only with Crossing, but also with most of his ambitious compositions from this period, Dzubas complemented his relationship to historic mural painting and fresco by drawing on their pictorial compression, the structural symmetries and asymmetries of their figural arrangement and cross-surface dialogues, and the sheer complexity of surface incident. Historic murals and large-scale paintings are significant visual resources for Dzubas, which he brought forward into contemporary painting to mobilize their formal content. When Charles Millard asked him about influences, Dzubas remarked, “But there are very few really that, I mean, I have, I always fall back on, on, on other centuries; now, if I say, ‘Whom do you like?’ Well, whom do I like, I mean, I like Tiepolo.”58 So, for example, one senses that Tiepolo’s frescos may well have been models, models that reinforced the wall-decoration techniques Dzubas learned early in life. For just as the intaco layer of lime plaster in buon fresco holds pigment, so the gesso layer in Dzubas’s paintings traps it. It is in this sense that Dzubas’s surfaces differ from Louis’s: they do not, in the Greenbergian sense, seem like “fabric… [that] becomes paint in itself…like dyed cloth…” as Greenberg described Louis’s facture, but rather, like matte layers that lock pigment in. Dzubas’s colors both meld with, yet do not entirely soak into, their cotton duck support.59

Contemporary responses to Dzubas’s work often posit a link to historical painting and, if not specifically to the Venetian tradition, to “European” painting on a grand scale.60 In what way Dzubas would develop the illusionistic, imagistic, compositional, and malerisch elements was anyone’s guess in 1977. Which brings us back to Greenberg’s thoughts on the artist. From the vantage point of 1977, Greenberg wrote that Dzubas had allowed the “Malerisch deep in him” to surface and fuse with the linearity apparent in work from the previous decade. From this merging “issued the ripest and most consistently successful, and certainly the most original art he has produced.”61 This is not only to praise the current over the earlier work, but also to urge the artist on. In fact, Greenberg’s entire essay reads like a personal plea to an artist he cared deeply about and whose earliest watercolors had genuinely touched him. If only Dzubas would return to “gray” and “black” or the “grayed blues and greens” that “ravished” Greenberg thirty years earlier. It’s as if Greenberg’s heightened, all but sentimental sensitivity to the hue, value, and saturation of Dzubas’s “dark” palette could return the artist to himself, so that he would become “possessed, possessed by himself even more than he is now.”62

Notes

It was Marilyn Morgan who suggested that her husband, the abstract painter Friedel Dzubas, appear in person at the offices of Partisan Review to answer the following classified ad: “PR CONTRIBUTOR and 13 year old son wish rooms for five weeks, beginning July, in country near swimming, other children. Clement Greenberg. Partisan Review, 1545 Broadway, NYC 19.”1 This was June 1948. Other contributors had placed ads—there is one from Mary McCarthy soliciting a “comfortable, small house”—but Dzubas and his second wife understood what meeting the major art critic of his time might hold for a younger artist. Despite Dzubas’s frequent claim that he had no idea he would be meeting Greenberg, the ad clearly posted the contributor’s name and the artist knew full well what he was about. And from the first, Dzubas and Greenberg liked each other. The artist’s opening gambit, delivered with charm and bravado, assured a mutual understanding: “‘Here I’ve been reading your stuff for the last… four or five years and I never could make head or tail out of it, but the main reason that I buy the stuff is because I can’t make head or tail of what you’re writing there,’ and we started to joke around.” So with his son, Danny, Greenberg moved into the guest quarters of Dzubas’s sixteen-acre, seventy-eight-dollar-a-month sublet in Redding, Connecticut for the summer. “Ya, he loved, he liked the, liked the house, liked the whole situation. Liked me. I liked him, too.”2

Thirty years on, in 1977, Greenberg agreed to write an essay—until now seemingly overlooked in the literature on Dzubas3—for a small retrospective, “Friedel Dzubas: Gemälde,” at the Kunsthalle Bielefeld.4 At less than a thousand words, the essay is important, not least because it addresses the career of a significant painter, one whom Greenberg included first in “Talent 1950,” an exhibition of younger artists at the Kootz Gallery (co-curated with Meyer Schapiro), and again almost fifteen years later in his 1964 exhibition, “Post Painterly Abstraction.”5 The decade-by-decade review at once summarizes Dzubas’s artistic practice up to the 1970s and casts retrospective light upon Greenberg’s 1964 accounting of the new art.6 By turns sympathetic and severe, Greenberg portrays an artist who in his estimation had yet to realize his full potential. For Dzubas, Greenberg’s opinion was unsurprising: in a letter to Dzubas accompanying the essay, Greenberg wrote with characteristic candor, “[The essay] wasn’t at all hard to write, I think because I permitted myself complete frankness & repeated things I’d already told you.”7 Greenberg’s overall tone in the essay is encouraging, if cautious: even as he reflects on his own preference for Dzubas’s early “painterly abstractions” in watercolor, he finds a Dzubas 1960s “linear” canvas at the Guggenheim “one of the best postwar items that the museum owns” (fig. 1). The key statement comes in the third paragraph and is directed to the artist, who, Greenberg insists, has yet “[to] enter […] the Promised Land with great, not just good, paintings.” Here he acknowledges Dzubas’s early originality while cleaving to the possibility that the day of major achievement will come. As he vouchsafes in the letter, “(It was written from the heart).”8 The point here is that for Greenberg to write this sort of essay was altogether unusual, an act of friendship on those grounds alone.9

Dzubas’s history is complex. He was born in Berlin in 1915, the child of a Jewish father and Catholic mother. As an adolescent during the rise of National Socialism in Germany, Dzubas (originally Dzubasz) suffered under the restrictions of Mischling status defined by Nazi race laws, which categorized such children as “mixed race.”10 A Mischling of the first degree or half Jew (Dzubas’s paternal grandparents were full Jews), Dzubas was forced to cope with the vagaries of emotional, professional, and political marginalization in pre-war Germany. Like many middle-class Jewish families at this time, the Dzubaszes—among them artists, book artisans, and graphic designers, textile managers, and translators—were politically left leaning. They identified primarily with the communists, although they were members of the official Jewish Community.11 Their anti-fascist/pro-Stalinist activities, such as attending meetings and printing and distributing pamphlets for communist-affiliated organizations, added tension to the already fraught social vagaries affecting their citizenship-status in the German Reich.12 Dzubas’s artistic training came fitfully, as anti-Semitic actions became more and more overt during the years 1931 to 1933, insinuating resistance to school and job opportunities for young people with Jewish blood that culminated in the Nuremberg Laws of September 12, 1935. When recognized as having Jewish blood, certain teachers and peers at various primary, secondary, and post-secondary educational institutions ostracized Mischlinge, although their legal status was not yet threatened. Opportunities for professional training were also circumscribed in the run-up to the National Socialist Machtergreifung on January 30, 1933.13 This fact alone precluded extended study with Paul Klee who would be dismissed from the Bauhaus at its dissolution in 1933. Whether Dzubas actually attended the Akademie der Künste in Berlin—a claim Dzubas made—cannot be confirmed by existing documentation.14

Like many young people who graduated from an Oberrealschule (high school)—as opposed to a Gymnasium from which students could expect to move on to university—Dzubas was apprenticed, in his case to a decorative painting firm, the M. J. Bodenstein Wohnungs-und Dekorationsmaler.15 There he was schooled in the art of fresco and other techniques related to wall decoration. Dzubas may have learned graphic arts and book design, skills he would depend on in his early years in America, from his uncle Wilhelm Dzubas, a respected graphic designer and decorative painter in Berlin16 and from another uncle, Hermann Dzubas, who owned a Buchdruckerei in Berlin that had published Die Rote Fahne, a communist newspaper.17

The systematic persecution of Volljuden and Mischlinge put in place by the Nuremberg Racial Laws in 1935 catalyzed the hurried formation of Jewish Youth Agricultural Training Camps, the expressed aim of which was to obtain visas to the United States, Palestine, or South America.18 Between 1936 and 1938, Dzubas trained at one of the few non-Zionist youth training camps, in Gross-Breesen, Silesia.19 It was through this program that Dzubas finally emigrated—as a farmer—to the United States in 1939 at the age of twenty-four, using in addition to his given name the Americanized “Frank Durban.” He was among the first trainee émigrés to enter Hyde Park Farmlands in Burkeville, Virginia, a settlement formed in the United States explicitly for the purpose of receiving trainees from Gross-Breesen. Here he remained with his German wife, Dorothea Brasch, for his first seven months in the United States; he left the settlement for New York City in May 1940.20

In less than a year, after several freelance jobs in graphic design—while bussing tables or making food deliveries—a chance meeting with William B. Ziff, Chairman of Ziff Publishing Company, resulted in a full-time position at the Ziff publishing house in Chicago, where for the next four years he worked as a commercial artist leading a book design team. Dzubas fell in with “a very aware, very sharp intellectual group of writers in Chicago, and I got very close to them and they were very well informed [in] thought, politics, literature, etc. Also art.” It was through this group that Dzubas began reading the Trotskyist New York intellectuals who wrote for the Partisan Review. At the same time, Dzubas was working in watercolor and had been accepted into several “Annuals” under the aegis of the Art Institute of Chicago.21 Returning to New York late in 1945, he engaged marginally with artists painting in the Abstract Expressionist style. By 1948, Dzubas had entered into a productive personal and professional relationship with Katherine S. Dreier, contributing his graphic services and art to her organization, Société Anonyme, and had in effect launched his artistic career in New York by befriending Clement Greenberg that same year at the offices of Partisan Review.22

So what did Greenberg actually say about the work? It’s important to understand that for the greater part of thirty years, Greenberg believed in this artist. But by 1977, his claim was that Dzubas had yet to construct a solid foundation for his future artistic development; that he had failed to “follow up on his achievements and achievedness”; that, instead, he had “let it all lie scattered.”23 Greenberg felt Dzubas had not yet done what would have been necessary—had in a sense refused to bear down on, to dig deeper into a clear artistic identity. This is what perplexed the critics and what earlier in his career had provoked the English art dealer John Kasmin’s exasperation: “You’re here, you’re there…. And it’s difficult for us to cultivate a certain taste if it seems that jumpy.”24 Dzubas’s seeming inconsistencies in approach—his shifts from expressionistic cursive gestures in the 1950s, to clean-edged, lucid color shapes against large areas of active white space in the 1960s, and on to loose, dynamically-arrayed color blocks in the 1970s—ultimately prompted Greenberg to aver that Dzubas’s art was indeed original, but this originality was somehow “surreptitious.” Dzubas had “fooled everybody, including myself as well as such a good critic as Michael Fried.” What he meant, of course, was that over the years, Dzubas had allowed himself to be seen as a less impressive painter than was in fact the case.25

In eight paragraphs, the narration goes like this. As an Abstract Expressionist painter in the 1950s, Dzubas was poised to “become one of its masters, a junior one, but a master nonetheless.” Greenberg points to Dzubas’s 1955 [sic] painting in the Whitney Museum collection, Yesterday, (1957; fig. 2), a large (44 ½ by 108 ¾ in.) horizontal abstract, as evidence, comparing it favorably to the museum’s Pollock and their “de Koonings and Kline.”26 Immediately, however, he gets to the crux of the problem as he sees it—Dzubas’s tendency to compose his canvases, to “fasten […] down all four corners,”27 to fill up spaces rather than leave them open, to, in effect, preclude the “indeterminate spaciousness” that the critic valued at that time.28 Yet Dzubas finally stepped beyond these self-limiting mannerisms when, in the 1970s, he combined his 1960s linear style with what Greenberg called a malerisch or painterly tendency.29 (See fig. 3.)

Greenberg had suggested that such a synthesis originated within the practices of painterly abstraction, the idea being such a revision was effected through a fusion of “clarity and openness.”30 Exemplary in this regard were works by artists “like Still, Newman, Rothko…” et al.31 Dzubas extended these artists’ revisions by using contrasting “instrumental qualities”—thinned paint surfaces and bare areas of canvas as against “the density and compactness” of Abstract Expressionism—thereby achieving the “freshness” characteristic of the new art.32

Greenberg looked beyond the context of Cubism to Venetian art for the soil in which “painterliness” had taken root: “The painterliness itself derived from a tradition of form going back to the Venetians. Abstract Expressionism—or Painterly Abstraction, as I prefer to call it—was very much art, and rooted in the past of art.”33 In describing Dzubas’s melding of old and new, then, Greenberg might have drawn on this very notion, for Dzubas was in thrall to fresco mural painting, not only by Giotto, but also by Titian and Giambattista Tiepolo, in particular the latter’s frescos created for the Residenz at Würzberg. Frank Stella took up the notion that Dzubas folded his early training as a Dekorationsmaler into his painterly vision when he wrote, “Early watercolors, decorative house painting, and commercial illustration all came together for him.”34 Like Greenberg, Stella understood that the foundation of Dzubas’s style lay in the artist’s early training and apprenticeship in wall painting and graphic design, which he expressed in his pictorial responses to the rhythmic disposition of massed color groupings so characteristic of Venetian fresco painting.

A close look at Dzubas’s surfaces is key. Dzubas did not stain his canvases. Rather, he primed them with two, sometimes three layers of gesso.35 As he clearly stated to Charles Millard in 1982, “I never stained. The only time I stained was when I was still working with oil on, on, not on canvas but on old bed sheets, you know, when I soaked the bed sheet, practically, in turpentine and then stained with cheap house paint that I had into the soaked surface.”36 (See figs. 4 and 5.) Which isn’t to say he was opposed to the method of soaking and staining. He clearly rubbed and pushed his pigments into his ground. This is obvious from the finish of his work, where the weave of the cotton duck remains exposed. But Dzubas relied for this effect on the double characteristic of liquescence and resistance in his mediums, whether watercolor, oil, or later with Magna acrylic, which he began to use in 1965. Characteristic of the opaqueness he sought in his early gouache-like watercolors from the 1940s that feature wet into wet, frankly figurative or allusive images in a loose expressionistic style (fig. 6), his later surfaces, no matter how thinly painted appear opaque even as he scrubbed his medium into the warp and weft of the fabric.37 Dzubas’s primed and gessoed canvases in the 1960s held his color shapes on the surface, pooled, controlled, and contained by their serrated or smoothed edges (fig. 7). In the 1970s, Dzubas feathered out the opaqueness, in a gesture he referred to as “fading off” or “fading out.”38 That is to say, Dzubas molds, pushes, and eases his pigments into forms that meld with, even as they resist, their material surrounds (fig. 8). This would change in the early 1980s when he directed his assistant to prime the canvas in a new way. As he told the curator Charles Millard in 1982, “Instead of priming it so it would, it will hold the turpentine on the surface and kept it on the surface for a while where I can work it. It’s primed now so meagerly that the medium immediately sucks in and you can’t, really, you can’t dance around… you have to put it down and leave it, so to speak. Whatever you put down, it it’s not open to manipulation and you’re stuck with it.”39

Dzubas generally divides his production into decades.40 When the artist took up oils in earnest in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he created an overall calligraphic, painterly surface with multiple foci in the spirit of Pollock’s early surrealist automatism. From gestural abstraction in the 1950s, Dzubas moved into a short-lived stylistic phase in the early 1960s, in which he filled his canvases with tightly woven, black linear markings coursing through white or off-white grounds (fig. 9).41 Paintings from the later 1960s feature close-valued hues laid out in two or more shallow fields of color, each bounded by either serrated or clean edges on an otherwise bare primed canvas, so that while color shapes nest, overlay, or touch, they are held in check by what Barbara Rose characterized as “arrested motion” or “dynamic stability.”42 “Emptying-out” the canvas, leaving a few large color areas gently abutting or in kinetic tension seemed to the artist necessary “after the indulgences and the semi-organic chaos of Abstract Expressionism.”43 Simultaneous “centers” exist within a large white space, which for Dzubas became an “essential first…. where the immaculate white, the virginity of the white, plus the strength of the white provides the strength of the whole. The untouched surface, the unedited surface was a very important active element, the way I felt things, the way I saw things.” Each color area is activated by proximity to its neighbor, the entire surface fixed within a square field. Color per se gains prominence, which Dzubas situated in dialogue with the revealed areas of white, the white acting as “the emotional element to deliver my message.”44

Dzubas’s paint medium from 1965 to the end of his life in 1994 was an early version of the first acrylic paint, Magna, developed by Sam Golden and Leonard Bocour between 1946 and 1949. Morris Louis was among the artists, who include Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Kenneth Noland, to use this experimental medium.45 What Dzubas liked about it was that it displayed the fullest saturation available at the time while holding its color when thinly applied.46 Nearly as fluid as oil paint, the resin compound added resistance. “It doesn’t let itself be pushed around that easily…it will not let itself be violated, and an additional inducement was, you never quite know what you will get…. [And it is] never quite know[ing] what you get that prevents you also from being too facile.”47 Working with hues that held and yet could be laid down in thin applications allowed Dzubas to achieve the shallow space he sought, even as he insisted on retaining evidence of the brush not only in his color shapes, but also in the dappled surrounds he would develop in the next decade.

By the 1970s, Dzubas was creating overlapping or contiguous, attenuated tesserae and large, elongated rectangular shapes with rounded or modified corners using brushstrokes that left a clean edge, but for feathering generally at one end. Poised in tight relational groupings, these “phalanxes,” as curator Ken Moffett described them,48 are placed vertically, diagonally. Contrasting color groups in close values seem to thrust forward and recede in a contre-jour effect brushed in with pigment.49 Crossing (Apocolypsis cum Figuras, A. D. 1975) (1975), for example, is essentially a picture of shallow spaces that through motivic repetitions, group divisions, and directional thrusts achieves a gait simulating all-over spatial agitation, as if figures were not so much traveling across the surface as assembling for immanent action.

Turning to a tradition centuries old, Dzubas often worked from small sketches (or modelli)50 that he would scale up to gargantuan size. From color tests (fig. 10) to painted sketch (fig. 11), he then moved to tacking a canvas to the floor (fig. 12), applying gesso layers, and measuring and at times outlining his shapes in gesso.51 He would then prop the modello on a low easel and with paint brush in hand loosely scale up the color scheme he had previously worked out—as can be seen in a photo of the artist transferring his acrylic sketch (fig. 13). This working sequence was followed in the creation of Crossing, a painting thirteen and half feet high by fifty-seven feet across, commissioned by philanthropist Lewis P. Cabot and contracted by Joseph Henderson, president of the Artcounsel, Inc. for the Shawmut Bank in Boston.52 The process proceeds in several stages: a sheet of color tests and an acrylic sketch (fig. 14), a scale study in red crayon, charcoal, and graphite, conveying measurements used for transferring the shapes to canvas (fig. 15).53 Then a “cartoon” mock-up on which the outlined tesserae enclose numbers that correlate with the colors that would fill them, following an age-old stained-glass technique. Photographs of Dzubas at work on the painting show paint cans, brushes, oil sketch, and painted contours.54 Wes Frantz, Dzubas’s studio assistant from 1980 to 1987, viewed Dzubas at close range: “Friedel…liked the freedom to interpret both what he did and what he saw with the moment in mind. But it didn’t mean he was totally spontaneous. When I first saw his sketches that he turned into larger paintings I thought he was abandoning his motion of spontaneity, but quite the contrary. With Friedel’s painting the devil was in the details. If you compare closely a small sketch to a large painting, the large painting will have all the details that the small ones don’t. And it’s in those details that Friedel sought his identity.”55

It’s interesting that Dzubas had considered creating a fresco when the monumental Apocalypsis Cum figures/Crossing was first proposed for Shawmut Bank in 1973. He felt an affinity with master fresco painters such as Giotto and Tiepolo, with the whole of “Western tradition, rather than the visual phenomena of the last ten years in Europe and America.”56 He admitted having in mind Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel, which he had visited in the 1960s and early 1970s, claiming he wanted “to outdo Giotto… to put in everything I knew and felt, for better or for worse…. It felt right and good. A gut reaction, not intellectualization.”57 Not only with Crossing, but also with most of his ambitious compositions from this period, Dzubas complemented his relationship to historic mural painting and fresco by drawing on their pictorial compression, the structural symmetries and asymmetries of their figural arrangement and cross-surface dialogues, and the sheer complexity of surface incident. Historic murals and large-scale paintings are significant visual resources for Dzubas, which he brought forward into contemporary painting to mobilize their formal content. When Charles Millard asked him about influences, Dzubas remarked, “But there are very few really that, I mean, I have, I always fall back on, on, on other centuries; now, if I say, ‘Whom do you like?’ Well, whom do I like, I mean, I like Tiepolo.”58 So, for example, one senses that Tiepolo’s frescos may well have been models, models that reinforced the wall-decoration techniques Dzubas learned early in life. For just as the intaco layer of lime plaster in buon fresco holds pigment, so the gesso layer in Dzubas’s paintings traps it. It is in this sense that Dzubas’s surfaces differ from Louis’s: they do not, in the Greenbergian sense, seem like “fabric… [that] becomes paint in itself…like dyed cloth…” as Greenberg described Louis’s facture, but rather, like matte layers that lock pigment in. Dzubas’s colors both meld with, yet do not entirely soak into, their cotton duck support.59

Contemporary responses to Dzubas’s work often posit a link to historical painting and, if not specifically to the Venetian tradition, to “European” painting on a grand scale.60 In what way Dzubas would develop the illusionistic, imagistic, compositional, and malerisch elements was anyone’s guess in 1977. Which brings us back to Greenberg’s thoughts on the artist. From the vantage point of 1977, Greenberg wrote that Dzubas had allowed the “Malerisch deep in him” to surface and fuse with the linearity apparent in work from the previous decade. From this merging “issued the ripest and most consistently successful, and certainly the most original art he has produced.”61 This is not only to praise the current over the earlier work, but also to urge the artist on. In fact, Greenberg’s entire essay reads like a personal plea to an artist he cared deeply about and whose earliest watercolors had genuinely touched him. If only Dzubas would return to “gray” and “black” or the “grayed blues and greens” that “ravished” Greenberg thirty years earlier. It’s as if Greenberg’s heightened, all but sentimental sensitivity to the hue, value, and saturation of Dzubas’s “dark” palette could return the artist to himself, so that he would become “possessed, possessed by himself even more than he is now.”62

Notes