Pollock paints a picture. [Fig. 1] He intended to paint a picture, not to dance around the studio, tossing paint all over. When Robert Goodnough watched him actually toss paint all over his canvas, he was assuming that Pollock’s intention had been from the start to paint a picture. When Hans Namuth took the photograph, he was making the same assumption. Neither would have made the trip to Northampton otherwise. We art historians and critics think we know that Pollock intended to paint a picture, because a picture is what he did, not an oversized doodle. But in fact, Pollock’s picture is a picture not because we know but because we judge it to be one, and we so judge partly because we, too, like Goodnough and Namuth, assume that Pollock intended his work to be seen and appreciated as a picture. We must assume this, and the reason we do is that we have learned that pictures are intentional objects—in the sense that they are both the outcome and the bearer, the carrier, the medium of intentions on the part of their maker. As medium of intentions, pictures declare and make visible all sorts of intentions: say the intention to represent the world, or to tell a story, or to produce beauty, and the like. But before they are anything else, all pictures are declarations of the intention to make a picture. Pollock’s pictures are paradigms of such generalizations because they go a long way toward being reduced to declarations of the intention to make a picture, and nothing else. They push the issue to the point where judging that this intention has been fulfilled perhaps requires nothing but its recognition, as declared intention. Pollock puts considerable pressure on the viewer’s willingness to assume that his art consists of intentions made visible. It takes an eye trained in the history of this ever-growing pressure since Impressionism to make that assumption in confidence. The marks on the canvas are indices of intentionality, no doubt, but from what distance? The closer we look at the canvas, the more remote are the chances that this yellow stain, here, or this blob of white, there, were intended to have exactly the location and particular form that they have. Yet to an even closer look, total randomness seems excluded. To spot the intentional at the level of such detail is to marvel at the very slim chances that paint falling haphazardly on a canvas would form such fine rectilinear skeins as this one, here, not once, not twice, but eight times, in white, black, red and yellow. The true index of intentionality does not lies in the marks per se but in their improbability to be the product of mere chance.

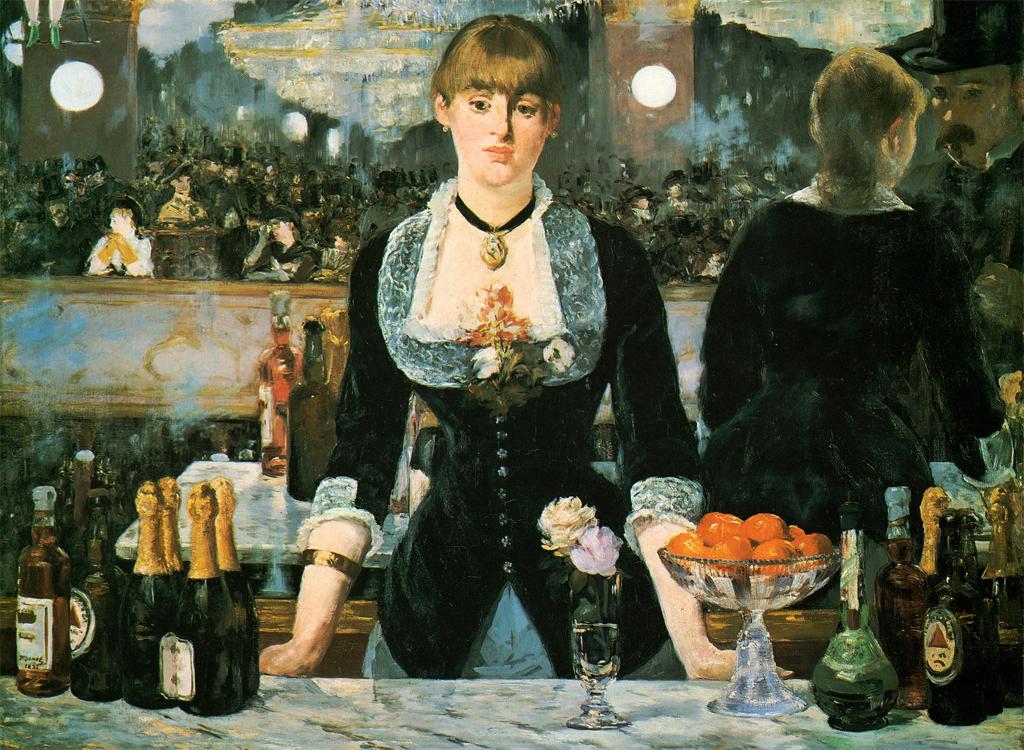

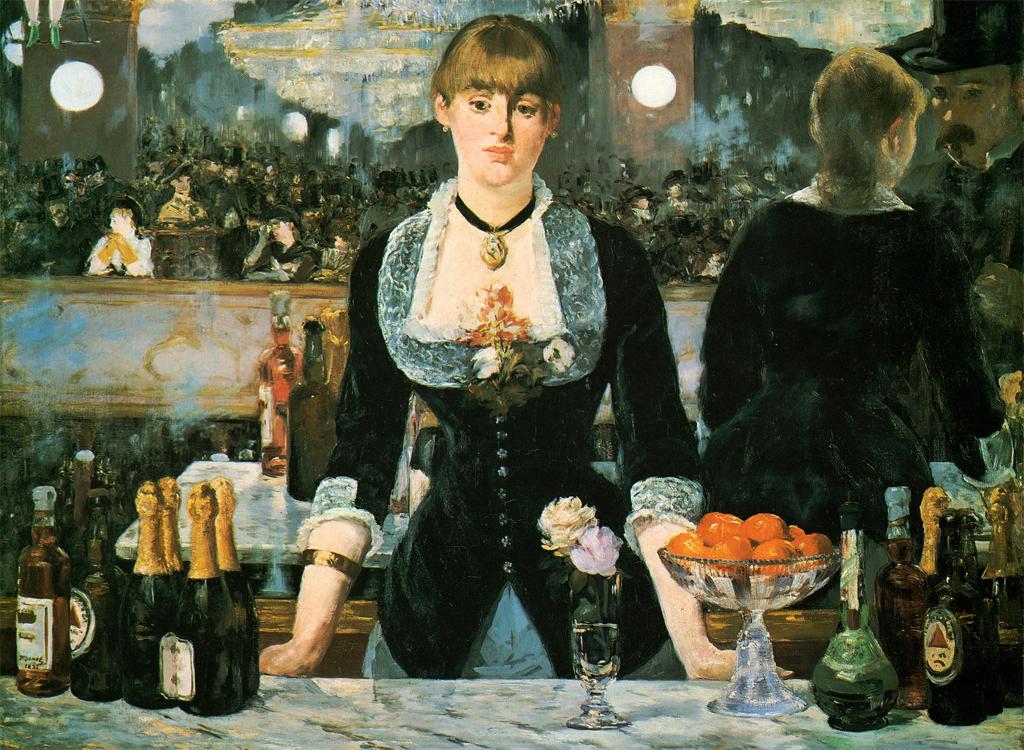

To say that Manet intended to paint a picture is at first sight a lot more trivial than to say the same about Pollock. It is however less trivial when gauged by the number of times his critics accused him of not finishing his canvases, or of not being able to round up “un tableau” while nevertheless churning out wonderful “morceaux.” The Salon jury that rejected him so many times during his career must have recognized Manet’s intention to paint a picture and judged that he failed in his delivery. He himself must have often been torn by the contradiction between his intention to paint a picture that the Salon public would understand, and the Salon jury accept, and his intention to paint a picture according to the new definition of a picture he was working towards. We of course salute him for not having compromised on the latter intention, and we tend to forget the former. Yet this is where the analogy with Pollock clicks. Lee Krasner recalls this about Pollock: “He asked me: ‘Is this a painting?’ Not is this a good painting, or a bad one, but a painting! The degree of doubt was unbelievable at times.”1 Manet had more confidence in his own talent than Pollock and perhaps had only contempt for the jury, but even he could not guarantee posterity’s verdict without a leap of faith. Posterity’s verdict, precisely, became a pressing issue, one that would take the place of Manet’s expectations regarding his success with the contemporary public, from that moment in 1881 when he learned that the degenerative disease that had hit him had dramatically shortened his life expectancy. This is when he decided to paint Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, his pictorial testament, the content of which is the explanation of how to look at all his paintings in order to recognize in them the new definition of a picture he had invented. [Fig. 2]

Lest you fear that I’m falling into what Wimsatt and Beardsley have dubbed “The Intentional Fallacy,” let me reassure you. I am calling Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère Manet’s testament basing myself on “external evidence”—the biography of the artist, his complaints to Baudelaire and others that he was misunderstood, the Salon criticism of the times, and so on—the kind of evidence Wimsatt and Beardsley say is not vulnerable to the intentional fallacy. But because Manet never explicitly said that Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère was his testament, I am also confronted with the task of demonstrating that it was, basing myself on “internal evidence.” The painting must show that it pertains to Manet’s intention to paint a picture, its failure in contemporary terms, and Manet’s hope that some day his intention would be recognized as having been successfully realized. And what must I show? Assuming that Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère is a picture whose intention was to paint a picture about the intention to paint a picture and how this intention should be recognized so as to be seen as successfully realized, I must show that the picture, therefore, uses clues as to how it was made in order to raise the question of why it was made the way it was. Throughout his life, Manet planted clues in his paintings, but they were not clues as to how the paintings were made, they were clues as to how the painting should be read so that his intention to paint a picture according to his own, novel definition of a picture, be understood. And throughout his life, these clues proved insufficient. The cat in Olympia was such a clue: it was there to tell the beholder that the painting had anticipated his presence before it, and that this preemption of the beholder, as Michael Fried calls it,2 belonged to the definition of a picture according to Manet. Contemporary criticism interpreted the cat in various ways, but always as part of the narrative content of the picture, never as part of the intended new definition of a picture. As I see it, Manet’s task when he projected to paint a picture-testament, was different: he first had to make sure that the question of why the picture was painted the way it was, the question of his intention, gets raised, by planting a clue to an indisputable proof of how the picture was painted the way it was. The clue in question would have to prove that chance must be ruled out as a plausible explanation. This is where Manet joins with Pollock.

How Manet painted pictures is of course light years away from Pollock’s drip technique. In 1881 and 1882, when he painted Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, Manet had embraced Impressionism since almost a decade, and Impressionism’s reputation is that its technique handles paint loosely, brings the aesthetic of the finished painting closer to that of the sketch, and disregards, even dismantles, traditional Renaissance perspective. In the case of Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, those features of Impressionism were compounded by an additional, and quite blatant impression that the construction of the painting was full of deliberate anomalies with regard to perspectival depiction of space.3 This was already noted by the Salon reviewers of 1882, and still approved by the twelve authors Bradford Collins rallied under the banner of “the new art history” in a book published in 1996 entitled 12 Views on Manet’s “Bar.” Those authors’ opinions converge with the one Anne Coffin Hanson had already presented as definitive in 1966, thirty years earlier:

The barmaid’s reflection does not seem to be where it should be, the reflected images of the bottles on the marble bar do not match their more tangible models. Historians have attacked the problem like sleuths, expecting to find some key to a logical and naturalistic explanation. There is none.4

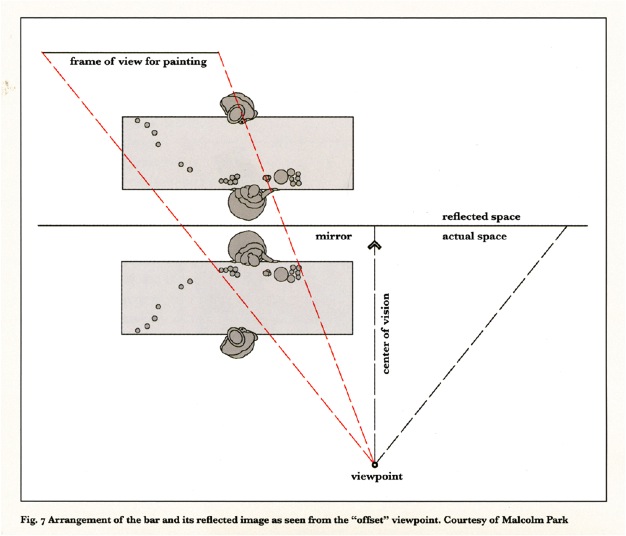

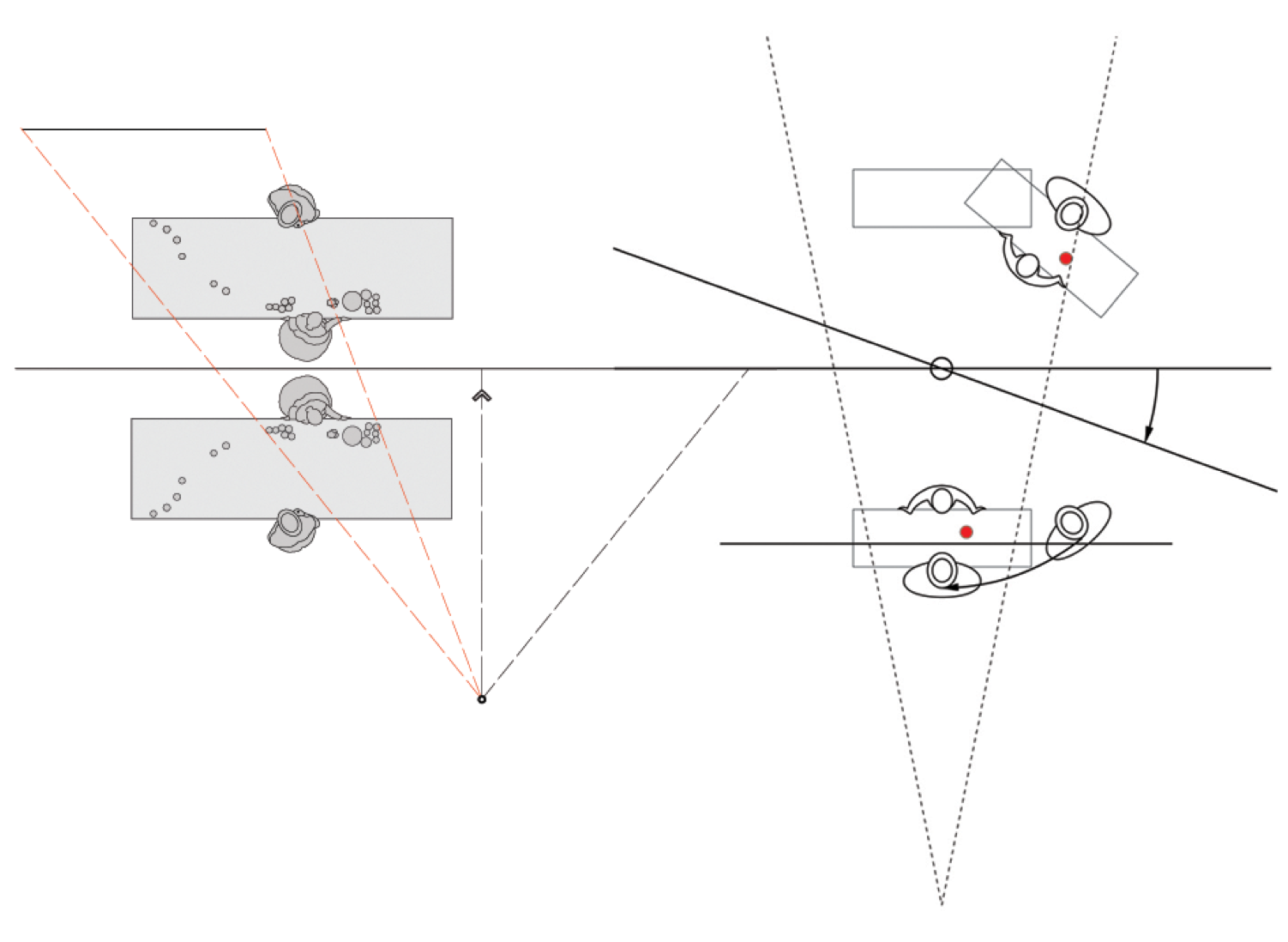

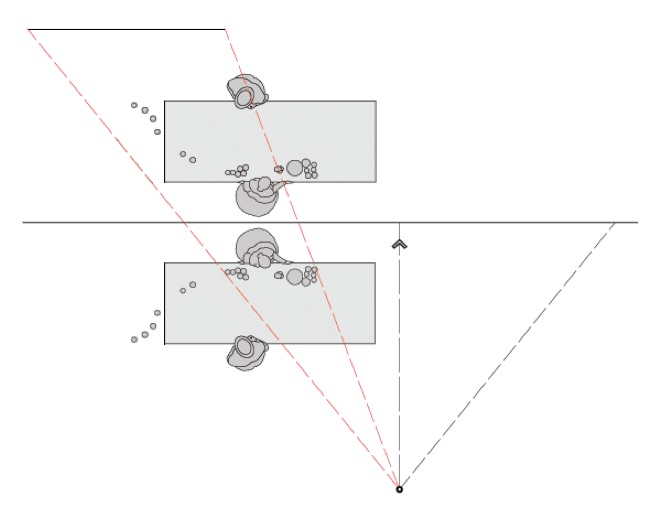

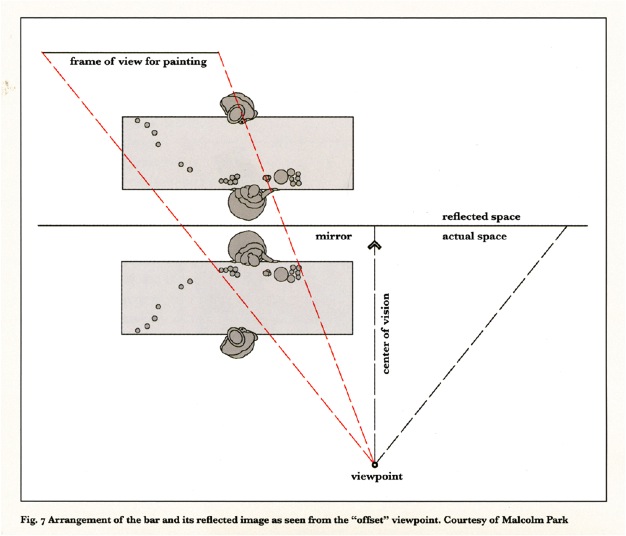

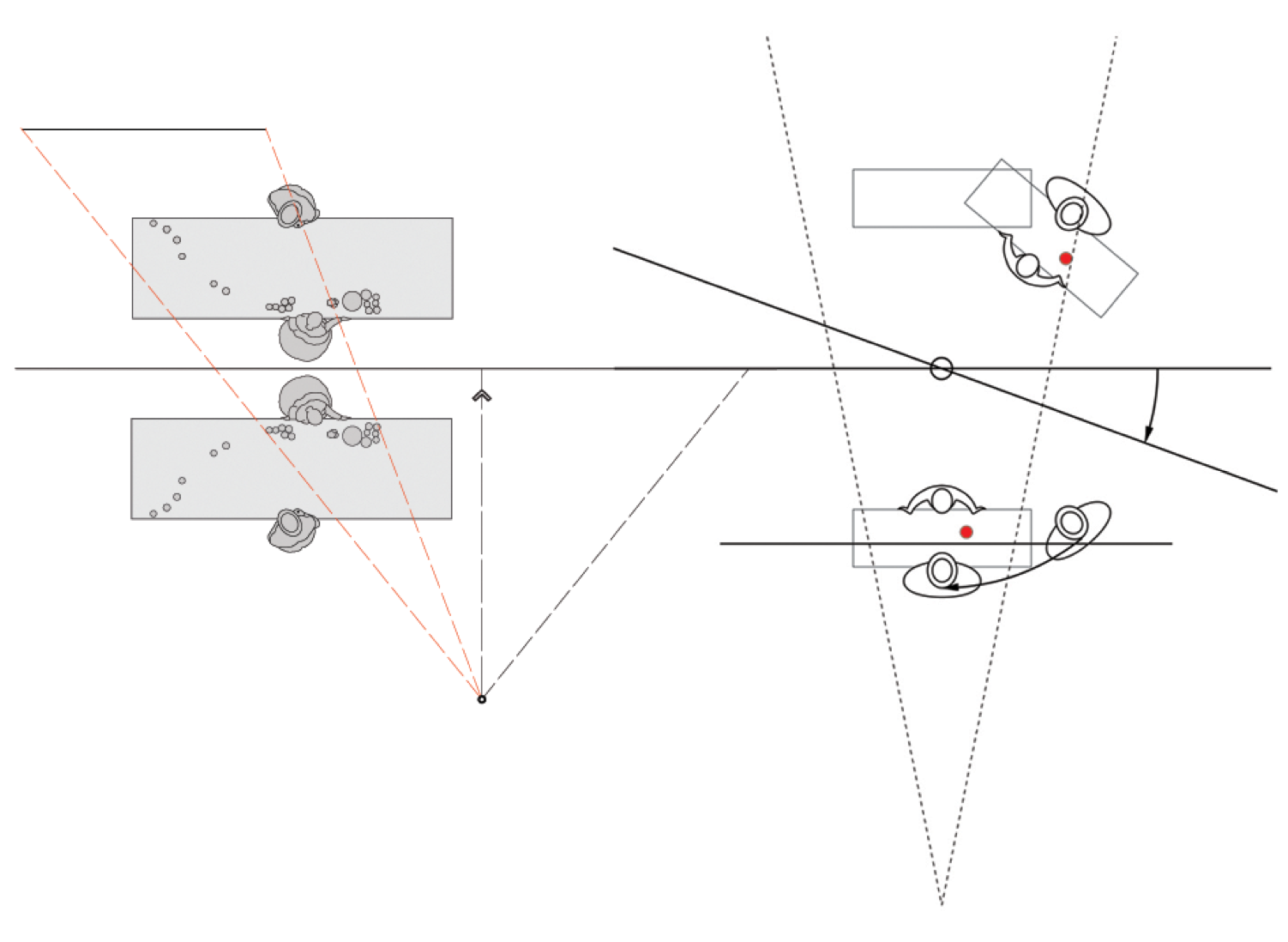

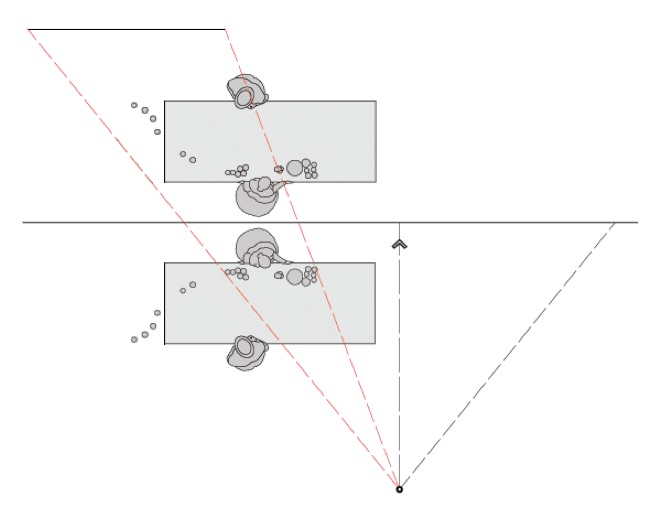

Things changed with the publication in 1998, in Critical Inquiry, of an article that demonstrated that the spatial construction of the painting was not at all anomalous but, on the contrary, done according to the strict rules of one-point perspective. Here I must apologize and beg you for your indulgence, because a lot in my talk from now on will appear utterly self-serving: I am the author of that article. For today’s purpose, I would by far prefer not to be. You will see why in just a second. For now, please bear in mind that the subject of my talk is not the spatial construction of Manet’s Bar. The latter serves only to establish the indisputable visual clue, the “internal evidence,” to use Wimsatt and Beardsley’s terms, that raises the question of Manet’s intention. Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère offers the art historian a peculiar, possibly even unique case study, inasmuch as the clue it contains leads him or her to a binary choice as to the artist’s intention and, from there, to divergent interpretations of the work or indeed, possibly of the artist’s whole oeuvre. I say binary choice because in 2001 somebody else proposed another explanation of the painting’s spatial construction, and one that calls with equal rigor on the strict rules of one-point perspective and is geometrically just as correct as mine, if not more. I am talking about an Australian scholar, Malcolm Park, who wrote a PhD dissertation entitled Ambiguity, and the Engagement of Spatial Illusion within the Surface of Manet’s Paintings.5 I learned of the existence of Park’s dissertation when I was at the Getty last year from Scott Allan, who, in 2007, curated a show of Manet’s Bar at the Getty Museum. I am indebted to him for having given me Park’s dissertation to read. On the occasion of the show, the Getty published a leaflet that contained a version of Park’s reconstruction of the painting’s scenography, in the form of a bird’s-eye view. Here it is. [Fig. 3]

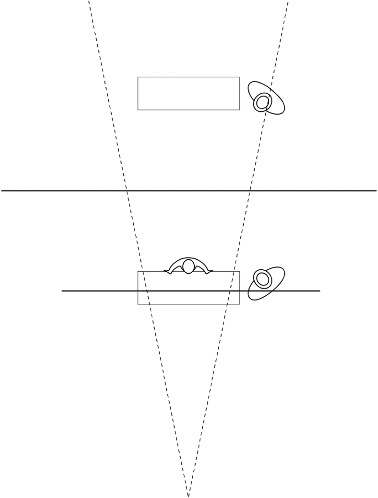

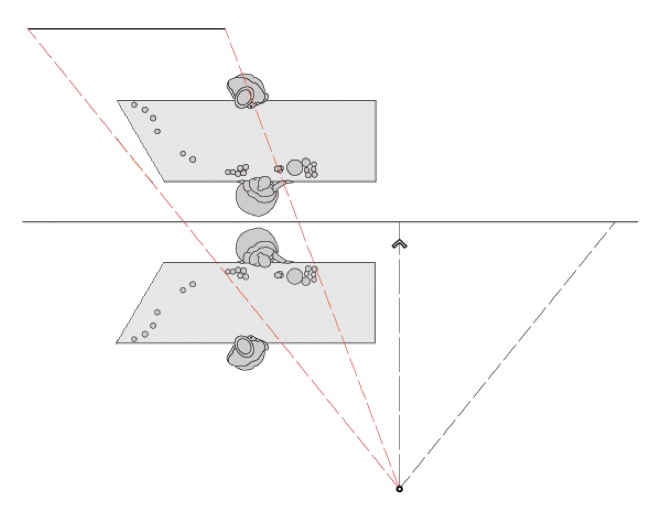

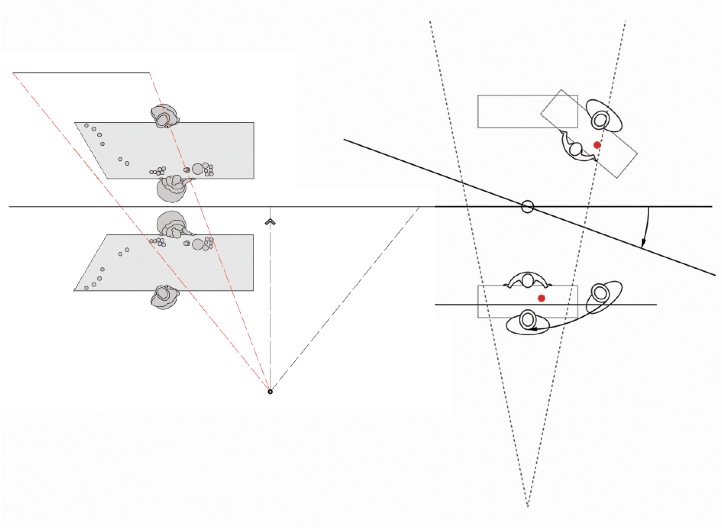

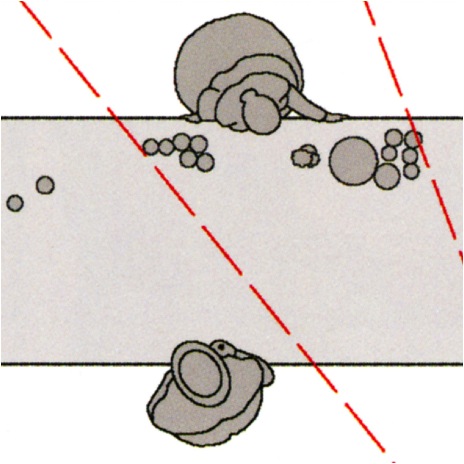

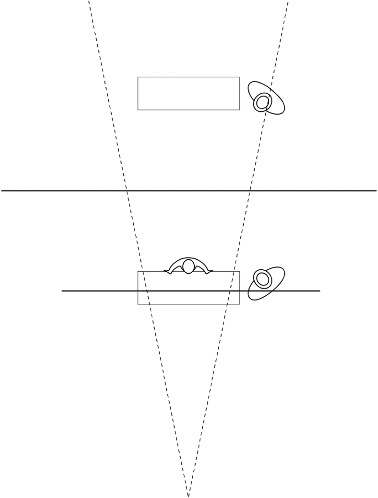

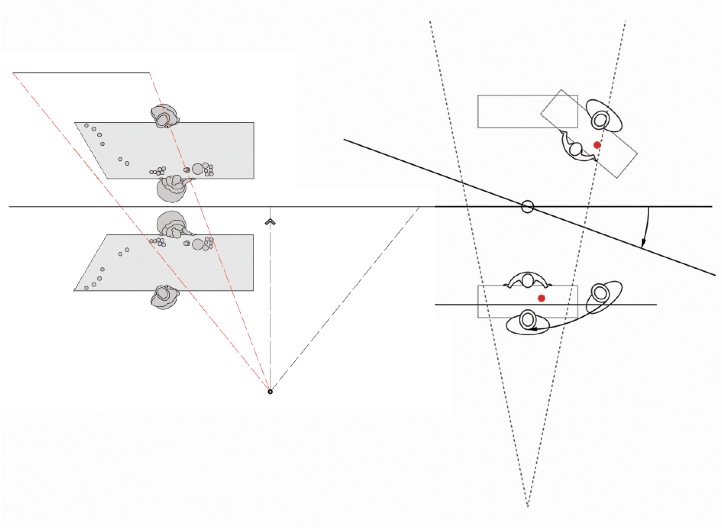

Malcolm Park 1) postulates that the spectator is placed far to the right of the scene, as in Manet’s sketch [Fig. 4] for the painting; 2) upholds that the visual pyramid corresponding to the painting has been cut from a wider frontal view; 3) therefore considers that the picture plane is an oblique section of the visual pyramid. (He shows it projected in the depth of the scene, whereas, as you will see, I treat it as a “Leonardo window” intersecting the counter’s surface, what amounts to the same); 4) arrives at the conclusion that the man in the top hat and the barmaid are not facing one another and don’t look at each other. [Fig. 5] Though strictly part of Park’s construction, the last point goes beyond geometry and opens the door to interpretation. Park’s four points taken together also make a fundamental conclusion: the painting abides so exactly by the laws of optics and the rules of perspective that it leaves no doubt that the construction was intentional and could not have been arrived at by chance.

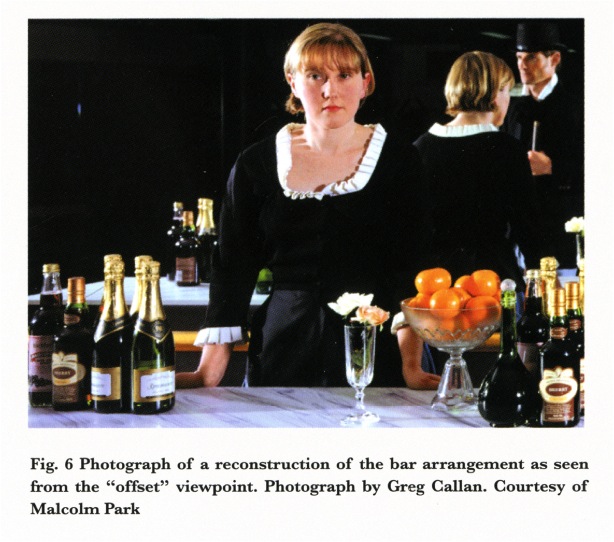

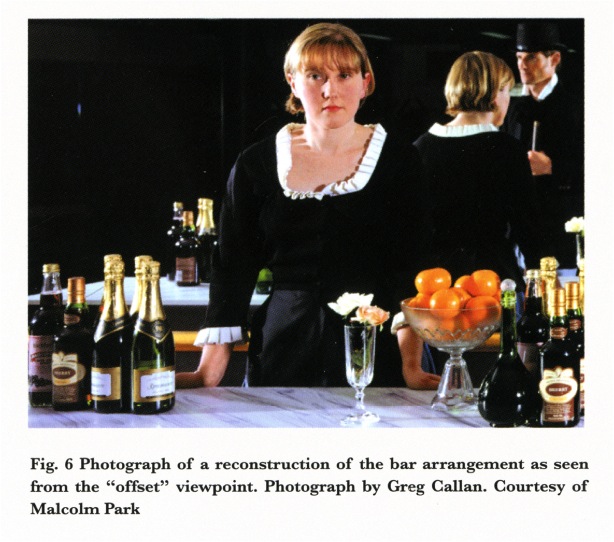

What was my reconstruction like? Let me juxtapose it to Park’s. [Fig. 6]

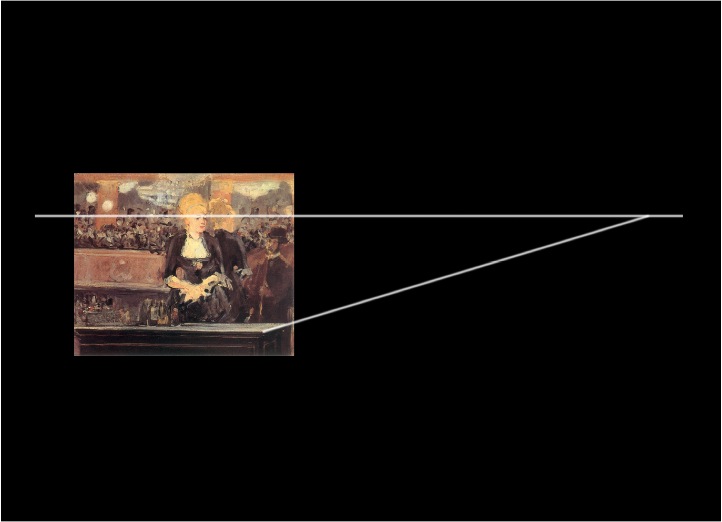

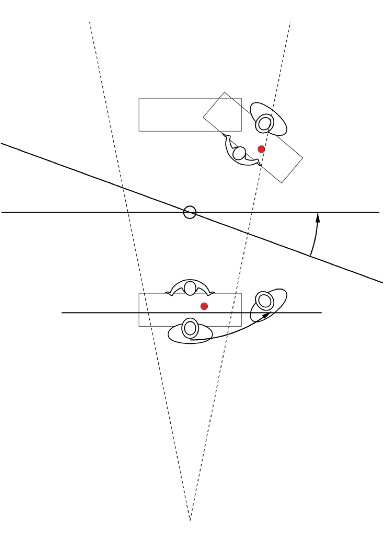

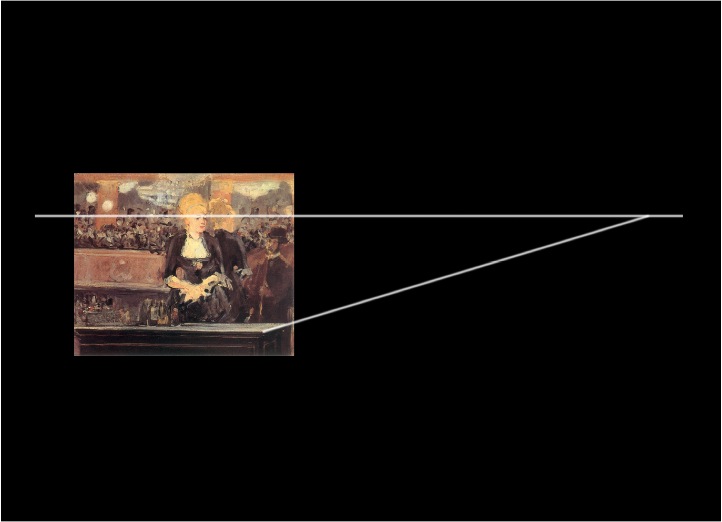

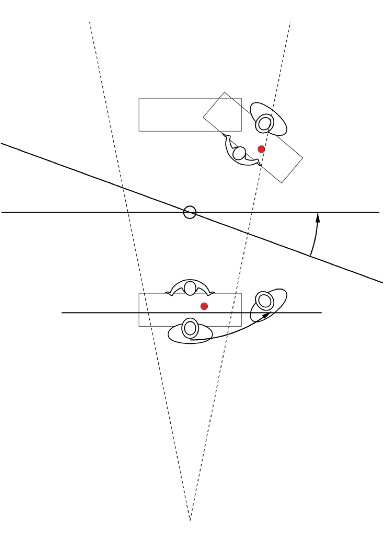

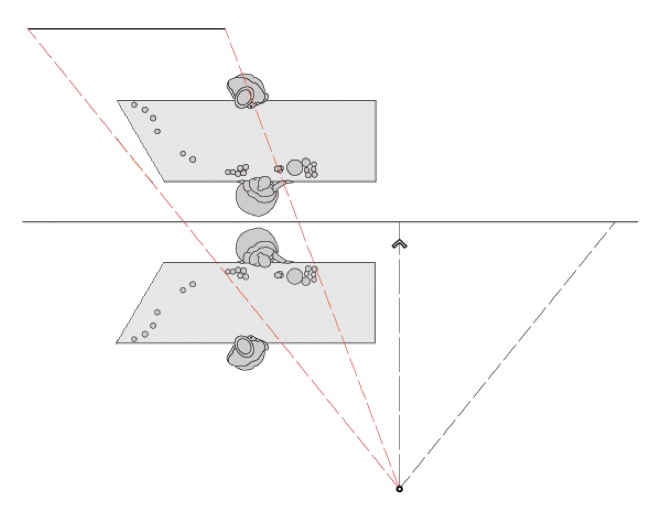

It 1) postulates that the spectator occupies a central position before the scene; 2) upholds that the painting is a composite image implying two (logical, not chronological) moments, where the reflection from moment 2 is “pasted” into the mirror from moment 1: at moment 1 [Fig. 7] the mirror is parallel to the picture plane and the man in the top hat is standing by the right side of the bar, outside the visual pyramid; at moment 2 [Fig. 8] the mirror has pivoted and the man has come to stand before the barmaid; 3) notices that what “locks” the composite image into place is the fact that one and the same reflection of the man in the top hat, in a mirror which in the meantime has pivoted, serves for his two successive locations “in reality” [Fig. 9]; 4) yields the hypothesis that the construction of Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, which is definitely Manet’s testament, is as unusual and precise as it is because the painter intended the double positioning of the man in the top hat to address some message to his posterity. Just as with Park, the last point goes beyond geometry and opens the door to interpretation. It also makes the same fundamental conclusion: that such a precise perspectival construction was intentional and could not have been arrived at by chance. And to that conclusion it adds another one, the fruit of reflection: that the locking into place of the man’s two positions by a single mirror-image was an intentional clue to the meaning of Manet’s testament.

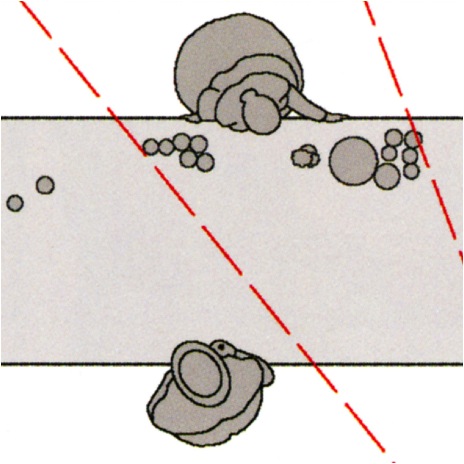

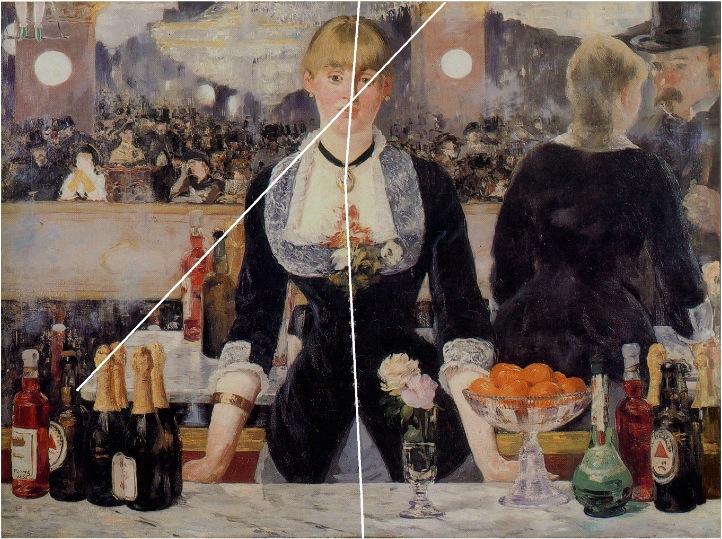

The interesting thing in the juxtaposition of Malcolm Park’s schema and mine is that although they are very different, they explain equally well the most blatant anomaly in Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, the off-center position of the couple in the mirror. Park’s schema actually explains more than mine. Above all, it accounts for the non-congruence of the bottles and their mirror image, an issue my construction bypasses.6 In the painting, the reflection of the group of bottles on the left side of the counter seems ill-placed: it should be near the counter’s edge that is the closest to the spectator, and not the furthest away. Park demonstrates that this group in fact sees its reflection pushed to the right, hidden by that of the barmaid. The bottles we see in the left part of the mirror actually form another group, an S-shaped garland that remains entirely outside the visual pyramid—a perfectly coherent solution, given the off-center position of the spectator, except that it forces Park to considerably stretch the bar on its left, with several unpleasant consequences. One of them seems to have been the victim of the Getty’s remarkable pedagogical concern for the public. Most of its shows come accompanied by explanatory wall texts or brochures catering to the widest audience, and the leaflet published on the occasion of the exhibition of Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère is no exception. This is probably the reason why the schema reproduced on that leaflet “cheats.” In order not to raise unwelcome questions with the average visitor, it runs the risk of raising a major objection from the specialist. Indeed, the schema one finds in Park’s dissertation is not that on the leaflet [Fig. 3]. I hope Park will allow me to correct the latter in conformity with figure F 38 of his dissertation [Fig. 10].

The trapeze-shaped outline of the bar’s tabletop, totally devoid of verisimilitude in the real world, imposed itself on Park on account of two features of the painting that contradict the schema published by the Getty. In the latter, the visual pyramid cuts through the left forward corner of the tabletop’s reflection. If this would be the case in the painting, we would see the bar’s mirror image being prolonged on about half its depth to the left border of the painting. But if we restored the tabletop to its rectangular form while respecting the distance between its reflection’s left forward corner and the left border of the painting [Fig. 11], two things would happen that are at odds with the visual evidence: first, the bottles, which we see sitting firmly on the bar’s tabletop in the mirror, would be floating mid-air in “real” space; and second, the vanishing line indicated by the left edge of the reflected bar would be much too flattened, as it is, indeed, in the photo reconstituting the scene, which the Getty’s leaflet reproduces [Fig. 12].

The hypothesis of a trapeze-shaped bar “lifts up” the left edge in conformity with the painting, so don’t get me wrong, Park’s model is correct. And if you disregard the issue of the bottles, mine is correct, too. So, we now have two competing models, equally valid in verifiable, scientific terms, from which to choose [Fig. 13]. Please forget that I’m utterly biased in this affair and bear with me: the question really is not what model is going to win the competition. Of course it’s mine, but that’s irrelevant, it’s not the subject. The theory issue, which is the real subject of my talk, is what court is qualified to pick one model over the other. Whatever model will be proclaimed the best will be by virtue of a certain choice I or you or anyone will have made regarding that court. For us to judge—to judge what? To judge which model is best, and thus what Manet’s intention might have been, and thus what line of interpretation to adopt, and thus how to read Manet’s testament, and thus what to make of his whole oeuvre and legacy—for us to judge, we must first, or by the same token, elect the legitimate seat of judgment. To the one that I elect, I give the name: aesthetic intuition. I feel genuinely sorry for Malcolm Park that he made my case so easy by systematically choosing the counterintuitive path, but here again, theory is the issue. We all have our theoretical inclinations, our sense of professional ethics and politics, our more or less consciously theorized ideology, what Althusser dubbed the spontaneous philosophy of scientists. I try to be as upfront with mine as possible: its name is aesthetic intuition. If I were to risk a name for Park’s, I would entitle it: Against Intuition. By paraphrasing Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation or Feyerabend’s Against Method, I want to suggest that it makes a lot of sense to be against intuition. It is a real option, a serious theoretical choice.

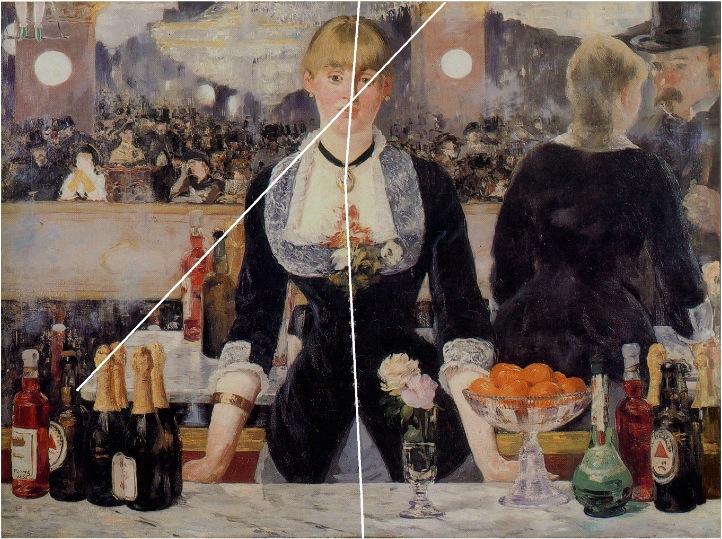

Yet for both Park and myself, everything started from an intuition, which he must have had like me, and which, for example, Ann Coffin Hanson did not have, that in spite of its apparent inconsistencies, the painting makes perspectival sense. From noticing that you are apparently not seeing the barmaid and her mirror image from the same viewpoint, you ask yourself: “where is the vanishing point?” And you soon notice that the only clue leading to the vanishing point is the left edge of the reflected bar. It is the only clearly indicated orthogonal. In order to determine the vanishing point, either one orthogonal and the horizon, or two orthogonals are required, but Manet offers us neither horizon nor second orthogonal. What he does, though, and very firmly, is have us facing the barmaid—Suzon was her name—and by the same token, have us stand right in front of the middle of the depicted scene. He has emphatically underlined the painting’s visual median line: the ridge of the nose, the medallion hanging from Suzon’s neck, her corsage, the row of mother-of-pearl buttons, and the pleat in her skirt, bisecting the triangular opening of her vest, compose a felt alignment, broken at the medallion, that projects a sort of externalized spine for both Suzon and for us, who stand before her. Thus placed, we are left to intuitively posit the vanishing point at the convergence of the line drawn from the lateral edge of the reflected bar and the visual median of the painting, that is, squarely in the middle of Suzon’s face. [Fig. 14]

The very strong impression of facing Suzon is an essential component of the emotional impact Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère has on us, and thus, of our appreciation of the painting. It is, typically, an aesthetic intuition. Aesthetic intuitions are first of all intuitions, in the everyday sense of hunch, in the psychological sense of an act of perception, and in the philosophical sense of an act of the imagination. What characterizes them not just as intuitions but as aesthetic is that they share with aesthetic experience their subjective, affective, non-conceptual nature, and with aesthetic judgments their reflexivity and their claim to universal validity, most often expressed as a claim to reflect factual truth. Our very strong impression of facing Suzon is a part of our aesthetic experience of the painting and is conducive to our aesthetic judgment on it. And while it is not a criterion—no one will claim that the painting is a masterpiece because we are facing Suzon—the fact is that we are facing her, and I challenge whoever has seen the painting in the flesh to dare contradict me.

Malcolm Park doesn’t: he thinks that Manet carefully fabricated our illusion of facing Suzon. It is not just that he settles for counterintuitive makeshifts such as the trapeze-shaped counter, it is that he actively fights intuition, his own included. At first he has had the same intuition as I, otherwise he would have been content with Anne Coffin Hanson’s opinion that it was useless to seek an explanation to the chaos. When he finds himself forced to have recourse to the expedient of the trapeze-shaped counter, Park has already judged that the oblique viewpoint is the only way to account for the painting’s construction. What surprised me most in his approach is that Park refuses to acknowledge the only clue leading to the vanishing point, and thus to the viewpoint: the left edge of the reflected bar. His reconstruction does not so much neglect the intuitive data as it actively denies them all relevance in favor of a very counterintuitive artifice that is difficult to believe. The result is that the extension of the bar’s left edge and the visual median of the painting are no longer intuitive indicators of the beholder’s position and become a lure intended to deceive him of her. Who would think of a trapeze-shaped table-top to account for a line that looks like an orthogonal but isn’t? The question arises: why such an artifice? And, more seriously: why, with what goal in mind, would Manet have wanted to deceive the beholder? The question is particularly acute regarding the lack of eye contact between the two protagonists, which, so far as I can recall, runs counter to all exegeses of the painting but is not without plausibility. The vexed question of the artist’s intention cannot always be avoided, as is demonstrated by the very rare, perhaps unique case of Manet’s Bar, where the choice between two reconstructions of the work that are equally plausible, geometrically speaking, rests by necessity on the historian’s speculation about Manet’s intention. In the absence of “external evidence” (a piece of writing by the artist, the reviews of the critics, the testimony of contemporaries, etc.), what access do we have to the artist’s intentionality? None other, I would argue, than what I called aesthetic intuition. Is it methodologically trustworthy? The question will not be settled here, but it is raised.

© Thierry de Duve

October 2009-February 2010

Notes

Pollock paints a picture. [Fig. 1] He intended to paint a picture, not to dance around the studio, tossing paint all over. When Robert Goodnough watched him actually toss paint all over his canvas, he was assuming that Pollock’s intention had been from the start to paint a picture. When Hans Namuth took the photograph, he was making the same assumption. Neither would have made the trip to Northampton otherwise. We art historians and critics think we know that Pollock intended to paint a picture, because a picture is what he did, not an oversized doodle. But in fact, Pollock’s picture is a picture not because we know but because we judge it to be one, and we so judge partly because we, too, like Goodnough and Namuth, assume that Pollock intended his work to be seen and appreciated as a picture. We must assume this, and the reason we do is that we have learned that pictures are intentional objects—in the sense that they are both the outcome and the bearer, the carrier, the medium of intentions on the part of their maker. As medium of intentions, pictures declare and make visible all sorts of intentions: say the intention to represent the world, or to tell a story, or to produce beauty, and the like. But before they are anything else, all pictures are declarations of the intention to make a picture. Pollock’s pictures are paradigms of such generalizations because they go a long way toward being reduced to declarations of the intention to make a picture, and nothing else. They push the issue to the point where judging that this intention has been fulfilled perhaps requires nothing but its recognition, as declared intention. Pollock puts considerable pressure on the viewer’s willingness to assume that his art consists of intentions made visible. It takes an eye trained in the history of this ever-growing pressure since Impressionism to make that assumption in confidence. The marks on the canvas are indices of intentionality, no doubt, but from what distance? The closer we look at the canvas, the more remote are the chances that this yellow stain, here, or this blob of white, there, were intended to have exactly the location and particular form that they have. Yet to an even closer look, total randomness seems excluded. To spot the intentional at the level of such detail is to marvel at the very slim chances that paint falling haphazardly on a canvas would form such fine rectilinear skeins as this one, here, not once, not twice, but eight times, in white, black, red and yellow. The true index of intentionality does not lies in the marks per se but in their improbability to be the product of mere chance.

To say that Manet intended to paint a picture is at first sight a lot more trivial than to say the same about Pollock. It is however less trivial when gauged by the number of times his critics accused him of not finishing his canvases, or of not being able to round up “un tableau” while nevertheless churning out wonderful “morceaux.” The Salon jury that rejected him so many times during his career must have recognized Manet’s intention to paint a picture and judged that he failed in his delivery. He himself must have often been torn by the contradiction between his intention to paint a picture that the Salon public would understand, and the Salon jury accept, and his intention to paint a picture according to the new definition of a picture he was working towards. We of course salute him for not having compromised on the latter intention, and we tend to forget the former. Yet this is where the analogy with Pollock clicks. Lee Krasner recalls this about Pollock: “He asked me: ‘Is this a painting?’ Not is this a good painting, or a bad one, but a painting! The degree of doubt was unbelievable at times.”1 Manet had more confidence in his own talent than Pollock and perhaps had only contempt for the jury, but even he could not guarantee posterity’s verdict without a leap of faith. Posterity’s verdict, precisely, became a pressing issue, one that would take the place of Manet’s expectations regarding his success with the contemporary public, from that moment in 1881 when he learned that the degenerative disease that had hit him had dramatically shortened his life expectancy. This is when he decided to paint Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, his pictorial testament, the content of which is the explanation of how to look at all his paintings in order to recognize in them the new definition of a picture he had invented. [Fig. 2]

Lest you fear that I’m falling into what Wimsatt and Beardsley have dubbed “The Intentional Fallacy,” let me reassure you. I am calling Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère Manet’s testament basing myself on “external evidence”—the biography of the artist, his complaints to Baudelaire and others that he was misunderstood, the Salon criticism of the times, and so on—the kind of evidence Wimsatt and Beardsley say is not vulnerable to the intentional fallacy. But because Manet never explicitly said that Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère was his testament, I am also confronted with the task of demonstrating that it was, basing myself on “internal evidence.” The painting must show that it pertains to Manet’s intention to paint a picture, its failure in contemporary terms, and Manet’s hope that some day his intention would be recognized as having been successfully realized. And what must I show? Assuming that Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère is a picture whose intention was to paint a picture about the intention to paint a picture and how this intention should be recognized so as to be seen as successfully realized, I must show that the picture, therefore, uses clues as to how it was made in order to raise the question of why it was made the way it was. Throughout his life, Manet planted clues in his paintings, but they were not clues as to how the paintings were made, they were clues as to how the painting should be read so that his intention to paint a picture according to his own, novel definition of a picture, be understood. And throughout his life, these clues proved insufficient. The cat in Olympia was such a clue: it was there to tell the beholder that the painting had anticipated his presence before it, and that this preemption of the beholder, as Michael Fried calls it,2 belonged to the definition of a picture according to Manet. Contemporary criticism interpreted the cat in various ways, but always as part of the narrative content of the picture, never as part of the intended new definition of a picture. As I see it, Manet’s task when he projected to paint a picture-testament, was different: he first had to make sure that the question of why the picture was painted the way it was, the question of his intention, gets raised, by planting a clue to an indisputable proof of how the picture was painted the way it was. The clue in question would have to prove that chance must be ruled out as a plausible explanation. This is where Manet joins with Pollock.

How Manet painted pictures is of course light years away from Pollock’s drip technique. In 1881 and 1882, when he painted Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, Manet had embraced Impressionism since almost a decade, and Impressionism’s reputation is that its technique handles paint loosely, brings the aesthetic of the finished painting closer to that of the sketch, and disregards, even dismantles, traditional Renaissance perspective. In the case of Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, those features of Impressionism were compounded by an additional, and quite blatant impression that the construction of the painting was full of deliberate anomalies with regard to perspectival depiction of space.3 This was already noted by the Salon reviewers of 1882, and still approved by the twelve authors Bradford Collins rallied under the banner of “the new art history” in a book published in 1996 entitled 12 Views on Manet’s “Bar.” Those authors’ opinions converge with the one Anne Coffin Hanson had already presented as definitive in 1966, thirty years earlier:

The barmaid’s reflection does not seem to be where it should be, the reflected images of the bottles on the marble bar do not match their more tangible models. Historians have attacked the problem like sleuths, expecting to find some key to a logical and naturalistic explanation. There is none.4

Things changed with the publication in 1998, in Critical Inquiry, of an article that demonstrated that the spatial construction of the painting was not at all anomalous but, on the contrary, done according to the strict rules of one-point perspective. Here I must apologize and beg you for your indulgence, because a lot in my talk from now on will appear utterly self-serving: I am the author of that article. For today’s purpose, I would by far prefer not to be. You will see why in just a second. For now, please bear in mind that the subject of my talk is not the spatial construction of Manet’s Bar. The latter serves only to establish the indisputable visual clue, the “internal evidence,” to use Wimsatt and Beardsley’s terms, that raises the question of Manet’s intention. Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère offers the art historian a peculiar, possibly even unique case study, inasmuch as the clue it contains leads him or her to a binary choice as to the artist’s intention and, from there, to divergent interpretations of the work or indeed, possibly of the artist’s whole oeuvre. I say binary choice because in 2001 somebody else proposed another explanation of the painting’s spatial construction, and one that calls with equal rigor on the strict rules of one-point perspective and is geometrically just as correct as mine, if not more. I am talking about an Australian scholar, Malcolm Park, who wrote a PhD dissertation entitled Ambiguity, and the Engagement of Spatial Illusion within the Surface of Manet’s Paintings.5 I learned of the existence of Park’s dissertation when I was at the Getty last year from Scott Allan, who, in 2007, curated a show of Manet’s Bar at the Getty Museum. I am indebted to him for having given me Park’s dissertation to read. On the occasion of the show, the Getty published a leaflet that contained a version of Park’s reconstruction of the painting’s scenography, in the form of a bird’s-eye view. Here it is. [Fig. 3]

Malcolm Park 1) postulates that the spectator is placed far to the right of the scene, as in Manet’s sketch [Fig. 4] for the painting; 2) upholds that the visual pyramid corresponding to the painting has been cut from a wider frontal view; 3) therefore considers that the picture plane is an oblique section of the visual pyramid. (He shows it projected in the depth of the scene, whereas, as you will see, I treat it as a “Leonardo window” intersecting the counter’s surface, what amounts to the same); 4) arrives at the conclusion that the man in the top hat and the barmaid are not facing one another and don’t look at each other. [Fig. 5] Though strictly part of Park’s construction, the last point goes beyond geometry and opens the door to interpretation. Park’s four points taken together also make a fundamental conclusion: the painting abides so exactly by the laws of optics and the rules of perspective that it leaves no doubt that the construction was intentional and could not have been arrived at by chance.

What was my reconstruction like? Let me juxtapose it to Park’s. [Fig. 6]

It 1) postulates that the spectator occupies a central position before the scene; 2) upholds that the painting is a composite image implying two (logical, not chronological) moments, where the reflection from moment 2 is “pasted” into the mirror from moment 1: at moment 1 [Fig. 7] the mirror is parallel to the picture plane and the man in the top hat is standing by the right side of the bar, outside the visual pyramid; at moment 2 [Fig. 8] the mirror has pivoted and the man has come to stand before the barmaid; 3) notices that what “locks” the composite image into place is the fact that one and the same reflection of the man in the top hat, in a mirror which in the meantime has pivoted, serves for his two successive locations “in reality” [Fig. 9]; 4) yields the hypothesis that the construction of Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, which is definitely Manet’s testament, is as unusual and precise as it is because the painter intended the double positioning of the man in the top hat to address some message to his posterity. Just as with Park, the last point goes beyond geometry and opens the door to interpretation. It also makes the same fundamental conclusion: that such a precise perspectival construction was intentional and could not have been arrived at by chance. And to that conclusion it adds another one, the fruit of reflection: that the locking into place of the man’s two positions by a single mirror-image was an intentional clue to the meaning of Manet’s testament.

The interesting thing in the juxtaposition of Malcolm Park’s schema and mine is that although they are very different, they explain equally well the most blatant anomaly in Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, the off-center position of the couple in the mirror. Park’s schema actually explains more than mine. Above all, it accounts for the non-congruence of the bottles and their mirror image, an issue my construction bypasses.6 In the painting, the reflection of the group of bottles on the left side of the counter seems ill-placed: it should be near the counter’s edge that is the closest to the spectator, and not the furthest away. Park demonstrates that this group in fact sees its reflection pushed to the right, hidden by that of the barmaid. The bottles we see in the left part of the mirror actually form another group, an S-shaped garland that remains entirely outside the visual pyramid—a perfectly coherent solution, given the off-center position of the spectator, except that it forces Park to considerably stretch the bar on its left, with several unpleasant consequences. One of them seems to have been the victim of the Getty’s remarkable pedagogical concern for the public. Most of its shows come accompanied by explanatory wall texts or brochures catering to the widest audience, and the leaflet published on the occasion of the exhibition of Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère is no exception. This is probably the reason why the schema reproduced on that leaflet “cheats.” In order not to raise unwelcome questions with the average visitor, it runs the risk of raising a major objection from the specialist. Indeed, the schema one finds in Park’s dissertation is not that on the leaflet [Fig. 3]. I hope Park will allow me to correct the latter in conformity with figure F 38 of his dissertation [Fig. 10].

The trapeze-shaped outline of the bar’s tabletop, totally devoid of verisimilitude in the real world, imposed itself on Park on account of two features of the painting that contradict the schema published by the Getty. In the latter, the visual pyramid cuts through the left forward corner of the tabletop’s reflection. If this would be the case in the painting, we would see the bar’s mirror image being prolonged on about half its depth to the left border of the painting. But if we restored the tabletop to its rectangular form while respecting the distance between its reflection’s left forward corner and the left border of the painting [Fig. 11], two things would happen that are at odds with the visual evidence: first, the bottles, which we see sitting firmly on the bar’s tabletop in the mirror, would be floating mid-air in “real” space; and second, the vanishing line indicated by the left edge of the reflected bar would be much too flattened, as it is, indeed, in the photo reconstituting the scene, which the Getty’s leaflet reproduces [Fig. 12].

The hypothesis of a trapeze-shaped bar “lifts up” the left edge in conformity with the painting, so don’t get me wrong, Park’s model is correct. And if you disregard the issue of the bottles, mine is correct, too. So, we now have two competing models, equally valid in verifiable, scientific terms, from which to choose [Fig. 13]. Please forget that I’m utterly biased in this affair and bear with me: the question really is not what model is going to win the competition. Of course it’s mine, but that’s irrelevant, it’s not the subject. The theory issue, which is the real subject of my talk, is what court is qualified to pick one model over the other. Whatever model will be proclaimed the best will be by virtue of a certain choice I or you or anyone will have made regarding that court. For us to judge—to judge what? To judge which model is best, and thus what Manet’s intention might have been, and thus what line of interpretation to adopt, and thus how to read Manet’s testament, and thus what to make of his whole oeuvre and legacy—for us to judge, we must first, or by the same token, elect the legitimate seat of judgment. To the one that I elect, I give the name: aesthetic intuition. I feel genuinely sorry for Malcolm Park that he made my case so easy by systematically choosing the counterintuitive path, but here again, theory is the issue. We all have our theoretical inclinations, our sense of professional ethics and politics, our more or less consciously theorized ideology, what Althusser dubbed the spontaneous philosophy of scientists. I try to be as upfront with mine as possible: its name is aesthetic intuition. If I were to risk a name for Park’s, I would entitle it: Against Intuition. By paraphrasing Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation or Feyerabend’s Against Method, I want to suggest that it makes a lot of sense to be against intuition. It is a real option, a serious theoretical choice.

Yet for both Park and myself, everything started from an intuition, which he must have had like me, and which, for example, Ann Coffin Hanson did not have, that in spite of its apparent inconsistencies, the painting makes perspectival sense. From noticing that you are apparently not seeing the barmaid and her mirror image from the same viewpoint, you ask yourself: “where is the vanishing point?” And you soon notice that the only clue leading to the vanishing point is the left edge of the reflected bar. It is the only clearly indicated orthogonal. In order to determine the vanishing point, either one orthogonal and the horizon, or two orthogonals are required, but Manet offers us neither horizon nor second orthogonal. What he does, though, and very firmly, is have us facing the barmaid—Suzon was her name—and by the same token, have us stand right in front of the middle of the depicted scene. He has emphatically underlined the painting’s visual median line: the ridge of the nose, the medallion hanging from Suzon’s neck, her corsage, the row of mother-of-pearl buttons, and the pleat in her skirt, bisecting the triangular opening of her vest, compose a felt alignment, broken at the medallion, that projects a sort of externalized spine for both Suzon and for us, who stand before her. Thus placed, we are left to intuitively posit the vanishing point at the convergence of the line drawn from the lateral edge of the reflected bar and the visual median of the painting, that is, squarely in the middle of Suzon’s face. [Fig. 14]

The very strong impression of facing Suzon is an essential component of the emotional impact Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère has on us, and thus, of our appreciation of the painting. It is, typically, an aesthetic intuition. Aesthetic intuitions are first of all intuitions, in the everyday sense of hunch, in the psychological sense of an act of perception, and in the philosophical sense of an act of the imagination. What characterizes them not just as intuitions but as aesthetic is that they share with aesthetic experience their subjective, affective, non-conceptual nature, and with aesthetic judgments their reflexivity and their claim to universal validity, most often expressed as a claim to reflect factual truth. Our very strong impression of facing Suzon is a part of our aesthetic experience of the painting and is conducive to our aesthetic judgment on it. And while it is not a criterion—no one will claim that the painting is a masterpiece because we are facing Suzon—the fact is that we are facing her, and I challenge whoever has seen the painting in the flesh to dare contradict me.

Malcolm Park doesn’t: he thinks that Manet carefully fabricated our illusion of facing Suzon. It is not just that he settles for counterintuitive makeshifts such as the trapeze-shaped counter, it is that he actively fights intuition, his own included. At first he has had the same intuition as I, otherwise he would have been content with Anne Coffin Hanson’s opinion that it was useless to seek an explanation to the chaos. When he finds himself forced to have recourse to the expedient of the trapeze-shaped counter, Park has already judged that the oblique viewpoint is the only way to account for the painting’s construction. What surprised me most in his approach is that Park refuses to acknowledge the only clue leading to the vanishing point, and thus to the viewpoint: the left edge of the reflected bar. His reconstruction does not so much neglect the intuitive data as it actively denies them all relevance in favor of a very counterintuitive artifice that is difficult to believe. The result is that the extension of the bar’s left edge and the visual median of the painting are no longer intuitive indicators of the beholder’s position and become a lure intended to deceive him of her. Who would think of a trapeze-shaped table-top to account for a line that looks like an orthogonal but isn’t? The question arises: why such an artifice? And, more seriously: why, with what goal in mind, would Manet have wanted to deceive the beholder? The question is particularly acute regarding the lack of eye contact between the two protagonists, which, so far as I can recall, runs counter to all exegeses of the painting but is not without plausibility. The vexed question of the artist’s intention cannot always be avoided, as is demonstrated by the very rare, perhaps unique case of Manet’s Bar, where the choice between two reconstructions of the work that are equally plausible, geometrically speaking, rests by necessity on the historian’s speculation about Manet’s intention. In the absence of “external evidence” (a piece of writing by the artist, the reviews of the critics, the testimony of contemporaries, etc.), what access do we have to the artist’s intentionality? None other, I would argue, than what I called aesthetic intuition. Is it methodologically trustworthy? The question will not be settled here, but it is raised.

© Thierry de Duve

October 2009-February 2010

Notes