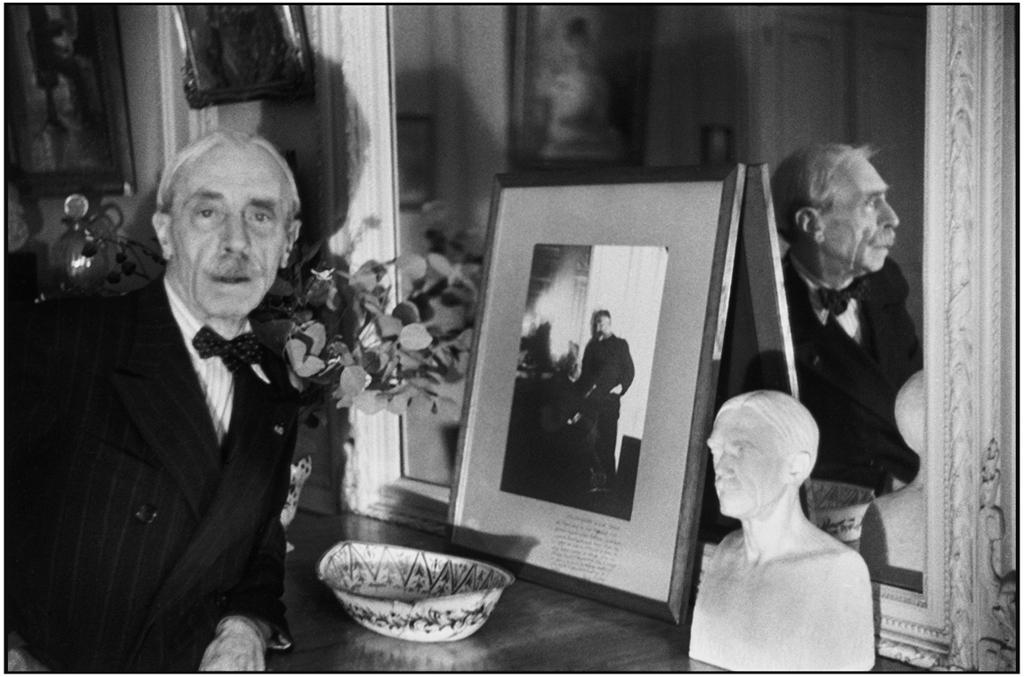

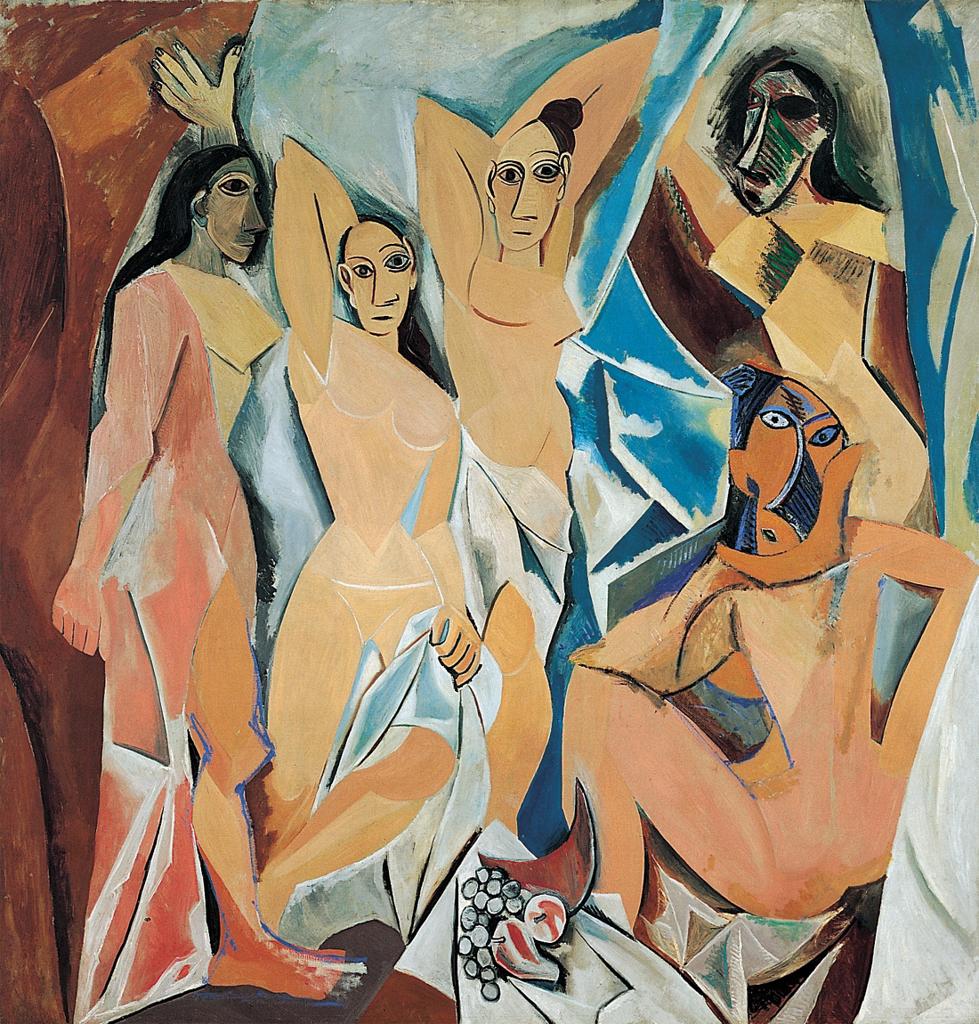

Matisse and Picasso: The Redemption and The Fall

We should give ourselves up to the lies of art to deliver ourselves from the lies of myth: it is by this very paradoxical and singular way of absorption into the framework of one of the “great works” of the Occident that Picasso belongs to myth. For if it is true that he always sought to combat myth, making him even more dependent on it, he only succeeded by turning myth’s own arms onto itself—that is, the “lie.”