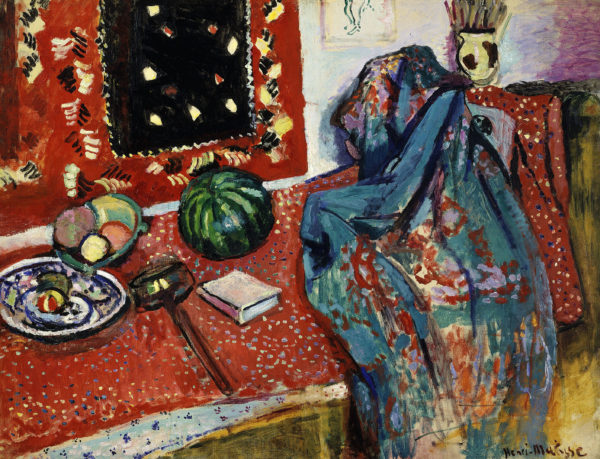

What Hegel Would Have Said About Monet

The question I promised to pose in this essay was whether we have an art—a nineteenth- or early-twentieth-century art—to which Hegel’s descriptions of world and consciousness can be seen to apply. I seem to be saying that they only apply, in the art I take seriously, in the negative—they are what French painting is out to annihilate. But for Hegel’s view of things to be worth refuting in this way—with Matisse’s special vehemence—surely in the first place there must have been pictures that exemplified it strongly, beautifully. And yes, there were.