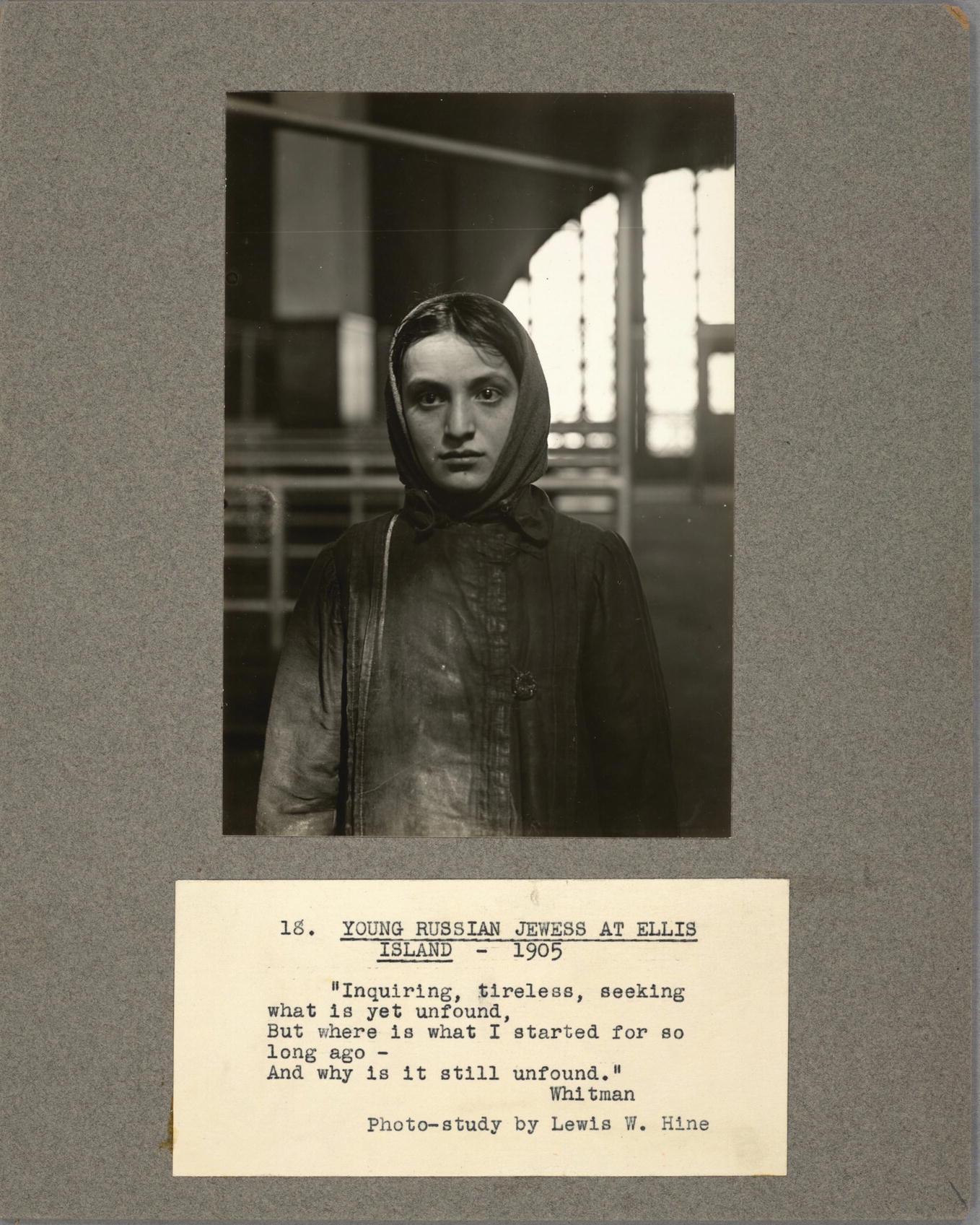

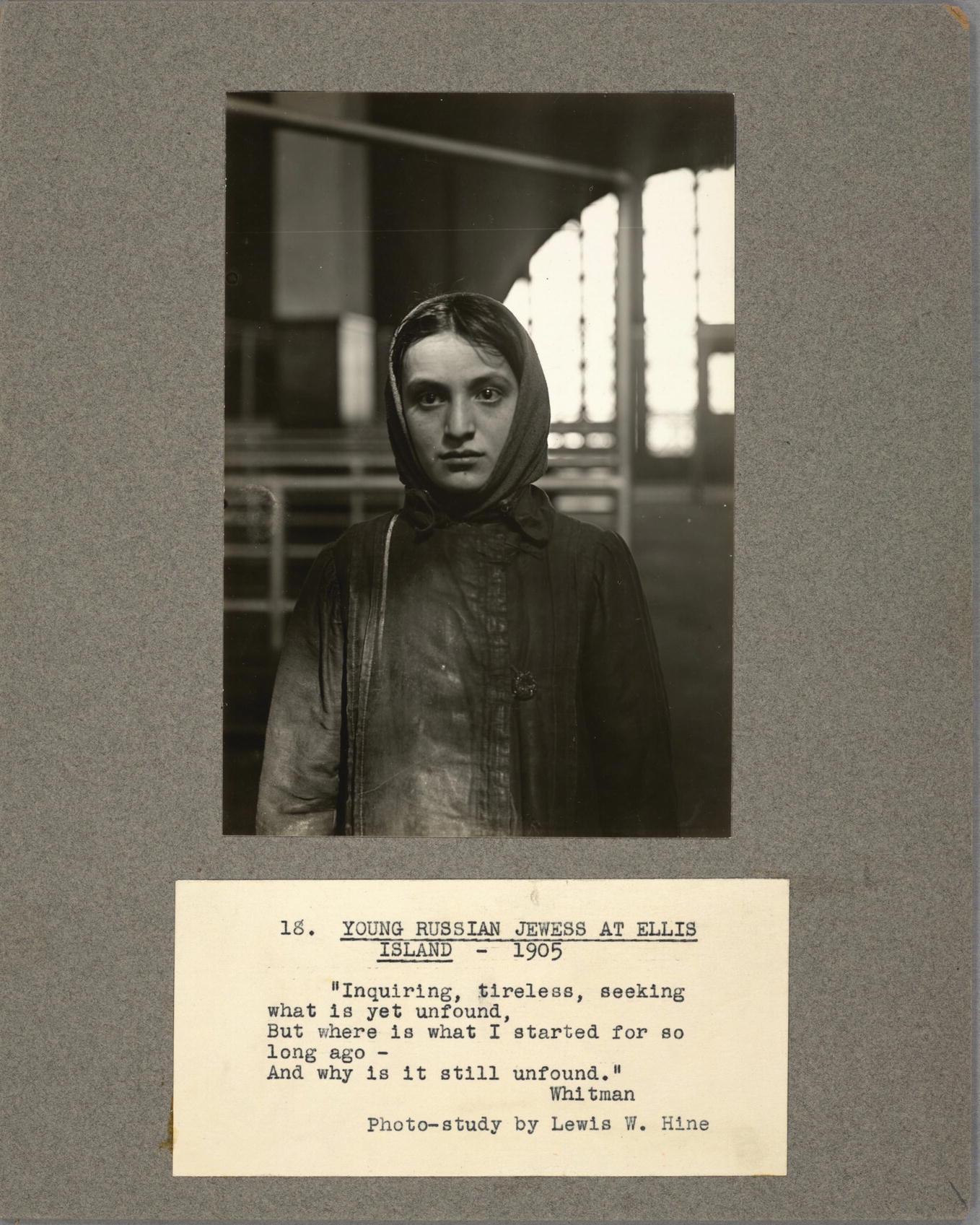

In this article, I present a critical framework for reconsidering social realist works that make central use of “idealizing means,” that is, representational means that signal the value of represented subjects. Social realist artists who aim to counter the social devaluation of poor and working-class people necessarily draw on idealizing means from traditional, ennobling sources in order to give the value of poor and working-class subjects a recognizable form. In the above photograph, for example, Lewis Hine makes compositional reference to the “great master” tradition and, in particular, to Vermeer’s genre paintings so as to key viewers to see this emigrant woman both in her class-specificity and with the idealizing religious rhetoric of the “beatifying light” that falls upon her. In drawing upon the idealizing means of “high” artistic traditions, Hine attaches poor and working-class subjects to the “metaphysical” or transcendental sense of value associated with these means. I call social realists like Hine “mystic realists.” Mystic, in my use of the term “mystic realism,” specifically refers to the use of idealizing means to secure representational pointedness about the value of subjects contending with unjust conditions.

However, mystic realists do not draw upon idealizing means simply or only to compel audiences to recognize the value of poor and working-class subjects. Idealizing means must further be made to express “motive values,” that is, values that motivate and guide social engagement and that challenge audiences with directives to social change. Mystic realists predominantly draw upon religious traditions for their idealizing means because, while idealizing means drawn from any prestigious representational tradition may underline the value of subjects, religious rhetoric seems to harbor a special capacity for motivational urgency. Religious rhetoric has the capacity to call upon audiences not only to recognize value or hold values but to act according to those values. Mystic realists seek to appropriate the motive urgency of religious cathexes and convictions in order to call audiences to social and political action. They seek not only to extend traditions that beatify ordinary and common conditions but to further beatify the inner striving of class representatives in a way that urgently motivates audiences to join a political struggle for better conditions.

In their recourse to traditional and especially religious means of signaling value and bearing values, mystic realists countenance a number of risks. They risk abstracting away from or covering over attention to specific conditions. They risk seeming to tie the need for better conditions to the “deservingness” of those subjected to unjust conditions—a sense of justice mediated by subjects’ ability to appear under the sign of normative values. And they risk interpretations of their work that write subjects into the wrong kind of religious teleology (the subject will have the recompense of heaven) rather than into the right kind of political teleology (we will struggle in solidarity with the subject to overcome injustice). Yet in contrast to conceptions of socially-engaged realism as a literalistic project of representation that avoids idealizing means in order to avoid these risks, mystic realists insist upon the indispensability of idealizing means both for the sake of portraying the dignity of their subjects and for the sake of building a shared political consciousness. Moreover, they insist that idealizing means do not inevitably divert audiences’ attention from specific conditions; to the contrary, by critically gauging the effects of rhetorical and craft choices, idealizing means can be made to key viewers to specific social conditions. Social realists who strictly tie their practice to literalistic means turn political confrontation into a matter of simply “seeing what’s there.” Yet a mere recognition of conditions that are real does not necessarily yield alignment with a struggle aimed at social repair, just as a mere recognition of the value of poor and working-class subjects does not necessarily yield political urgency. In certain contexts, one may indeed experience motive values as immanent to objective conditions—for example, when one has been mobilized as part of a collective struggle for better conditions. Just as patently, in other contexts, one may experience their knowledge of conditions, whether it be direct knowledge or knowledge drawn from representations, in a way that is disarticulated from and fails to lead to imperatives to social and political action. Mystic realists address this problem of disarticulation by making recourse to idealizing means and especially to the idealizing means provided by religious traditions. This recourse does not imply that one needs to have a religion to have motive values. Rather, religious traditions have a special utility for mystic realists because they are explicitly and unmistakably value-bearing traditions. For all that these traditions may mystify, they also bring analytical clarity to the relation between motivation and the valuing, idealizing, and hierarchizing of a better on which motive solicitations fundamentally (that is, metaphysically) depend. Where mystic realists are explicit about their relation to ennoblement and motive ideals, strictly literalistic (and strictly secular) projects of social representation are inexplicit. For mystic realists, papering over the relation between signal forms of valuing and political motivation serves neither the aim of producing urgency in response to class conditions nor even the aim of producing clarity about these conditions.

I: Sekula contra Mystic Realism

This conception of a mystic realist problematic first emerged in my thinking in response to the classic 1975 essay, “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning,” by photographer and critic Allan Sekula. In this essay, Sekula argues that claims about the meaning of a given photograph can never be developed solely on the basis of elements within that photograph. Instead, photographic meaning is “invented” through interpretations that attach elements within the photograph to the rhetoric of larger discourses. Sekula here attacks critics Benedetto Croce, Roger Fry, and Clive Bell for operating like a “photographic meaning” cartel that restricts interpretation to the discourse of expressionist-modernist formalism and restricts us from political interpretations that contest the status quo. For Sekula, formalist discourse thus masks the social character of its tendentious idealization of “art” and of its concomitant devolution of formal concerns “into mystical trivia.”1 In doing so, this discourse serves elite classes as a quasi-religious opiate that deadens consciousness of the social meaning of class sides by making meaning into a matter of mystifying abstractions and diffusively “spiritual” or “universal” feelings.

Sekula develops his claims through an image comparison of Hine’s 1905 Immigrants Going Down Gangplank, New York and Alfred Stieglitz’s 1907 The Steerage. Both works represent the same class of subjects—new or recent, impoverished European immigrants. In Hine’s photograph, the subjects are disembarking from a ship, and in Stieglitz’s photograph, they are crowded into a ship’s steerage section. For Sekula, if we attempt to base our interpretation of these photographs strictly on elements “within” the photographs, no sharp distinction between their respective overall meanings seems possible. Yet Stieglitz, in his magazine Camera Work, curates the original discursive context of The Steerage so as to singularly construct the meaning of the work in terms of its formal composition. For Stieglitz, the photograph’s “shapes” provide equivalents for the phenomenal alienation of a genius Artist, an alienation that captures diffuse but “universal” “feelings” (OTI, 42). In his 1942 article, “How The Steerage Happened,” Stieglitz narrates how ennui amongst the fashionable nouveaux riche company of the ship’s first class section prompted him to walk the deck until he gained a view of the steerage, where crowded conditions pushed passengers into teeming modernist shapes, shapes that elicited his immediate identification. The fortuitous detail of a man with a circular hat, who stood on the first-class deck opposite Stieglitz and also looked down at the steerage, further provided Stieglitz with a proxy figure for his own state of social alienation. As Sekula argues, photographic meaning, in Stieglitz’s account, emerges from an explicit and facile aesthetic equivalence between shapes and feelings, where the mediating term of the bourgeois artist’s alienation harbors a merely implicit—and equally facile—politics.

In contrast, Sekula claims that Hine’s photograph exhibits a “manifest politics and only an implicit esthetics” (OTI, 43). By presenting his photographs in the social work journal Survey and in Women’s Trade Union League and National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) publications, Hine positions himself as a social interpreter rather than as an aesthetic interpreter. Hine’s work documents specific social conditions with photography and with text in order to provide evidence and testimony that might prove instrumental in legislating and litigating against these conditions. Hine labors to present subjects both as clearly marked by a legally verifiable class of injuries and as undeniable bearers of human dignity. Perhaps surprisingly, Sekula takes issue with this second aim. Sekula’s appreciation for the sociological dimensions of Hine’s social realism modulates into depreciation of the aesthetic dimensions of his practice. Sekula describes Hine’s commitment to photographic compositions that give recognizable visual expression to the inner spirit and inner dignity of his subjects—that is, his commitment to producing outward signs of these inner truths—as “expressionism in the realm of ‘fact’” (OTI, 45). Sekula begins his essay by taking aim at expressionist formalism, but his more important target turns out to be social realist works that also harbor a form of expressionism, one that, in Sekula’s view, is no less susceptible to the mystifying abstractions of bourgeois liberalism.

For Sekula, the susceptibility of Hine’s work to mystifying abstractions stems from his commitment to nineteenth-century realists who aimed to produce a “mystical” sense of human communality. Sekula points to Hine’s lecture, “Social Photography,” which Hine concludes with a quotation from George Eliot’s 1859 novel, Adam Bede, that praises artistic representations of “those rounded backs and weather-beaten faces that have bent over the spade and done the rough work of the world.”2 Sekula wants his readers to notice how this description of “rounded backs” dampens our confrontation with the fact of a painful, difficult posture of field labor by interpreting this posture aesthetically as a matter of beautiful, rounded shapes. For Sekula, this kind of description is indicative of a nineteenth-century project of realism, shared by the likes of Tolstoy and Millet, that sought to heighten readers’ and viewers’ appreciation of the value of common people in the hopes that this would lead to a more capacious capacity for sympathy. Sekula writes:

Hine is an artist in the tradition of Millet and Tolstoy, a realist mystic. His realism corresponds to the status of the photograph as report, his mysticism corresponds to its status as spiritual expression. What these two connotative levels suggest is an artist who partakes of two roles. The first role, which determines the empirical value of the photograph as report, is that of witness. The second role, through which the photograph is invested with spiritual significance, is that of seer, and entails the notion of expressive genius. It is at this second level that Hine can be appropriated by bourgeois esthetic discourse, and invented as a significant “primitive” figure in the history of photography.3

According to Sekula’s gloss, “realist mystic” art means to educate our moral sentiments by expressing the “spiritual significance” of what it represents—a “nineteenth-century” discourse that, in Sekula’s view, amounts to nothing more than a sentimental ideology of “humane liberalism.” In designating Hine’s photographs as “realist mystic,” Sekula flags the idealizing character of Hine’s supposedly literal, documentary images, and he diagnoses the mystifying and corrupting influence of idealizing means on realist analyses of class structure. While Sekula begins his essay by contrasting Stieglitz’s insistence on abstract and spiritually diffuse meaning and Hine’s insistence on social and political meaning, Sekula makes it clear that, with the help of his term “realist mystic,” we are now to see that these discursive poles in fact recur microcosmically in Hine’s practice. Sekula thus interprets the susceptibility of Hine’s work in the seventies to modernist curation (museum exhibition of monumentalized prints with minimal contextualization) as not so much a cooptation of his work into a discourse of “modern bourgeois aesthetic mysticism” as a confirmation of its underlying complicity with this discourse (OTI, 41). For Sekula, the taint of any quantum of “mystic,” idealizing means or aims renders work no longer really “realism,” no matter how much of its makeup “realism” might account for, but mystification.

Sekula concludes “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning” by claiming that “all photographic communication” can be situated in relation to the binary poles represented by “symbolist” and “realist” discourses: as expression versus as reportage; as inner truth versus as empirical truth; as metaphoric versus as metonymic (OTI, 45). As this last pair of binary poles indicates, Sekula is deriving his binary schema from major literary theoretical texts on realism that have similarly defined a realist paradigm against the “other” of a modernist paradigm, most obviously Roman Jakobson’s 1956 essay, “The Metaphoric and Metonymic Poles.” Yet in Jakobson’s comparatively modest assessment, a metaphoric pole gains only a relative degree of predominance in verse (and most especially in the symbolist poem), while a metonymic pole gains relative predominance in prose (most especially in the realist novel). While he argues that genre theory will benefit from taking these relative predominances more deeply into account, Jakobson sees metaphoric and metonymic “poles” as in fact continually co-productive of all discourse. Because Sekula parcels out his binary pairings not to genres, as in Jakobson, but to competing ideologies, he seems to produce a false dilemma: we must choose to rigorously restrict aesthetic elements that might take on an expressionist cast, or we must allow the politics of realist acuity to be corrupted.

Previously, a similar binarization of terms had eventually led the Partisan Review to the opposite conclusion. Partisan Review critics had initially aimed to improve left-realist art and literature (and to untether it from the USSR’s reactionary “realist” program) by advocating for a move away from blunt political editorializing and toward a more limpid and formally innovative disclosure of social critique. Yet due to their polarization of the aesthetic and the political, Partisan Review critics ended up seeing the need to mount a cultural defense of fully “autonomous” high-modernist art. Given disruptive media-historical conditions that inhibited artists’ sense of their ability to compete for a broad public without allowing their work to suffer aesthetically, Clement Greenberg argued that artists should resign from any explicit engagement with politics and instead assert autonomy by involuting into abstraction of their media.4 By 1939, Partisan Review critics thus by and large dropped realism from their cultural program and named it as not really art. Few literary or art critical arguments have proven quite so influential or enduring, for academia and major cultural institutions alike, as the anti-realist polemics of Partisan Review critics Greenberg and Lionel Trilling (especially, in recent decades, as combined with the arguments of Frankfurt School critical theorists). Because these polemics have come from left-wing critics, they have supplied political cover for presupposing the aesthetic superiority of works that retreat into “autonomy” over and above socially directive and publicly oriented works.

As with the case of the Partisan Review, Sekula’s polarization of terms leads him to lose track of the complexity of what he initially aims to comprehend. How do differing rhetorical uses of means transform and reinvent meaning? And thus, how might specific aesthetic means, whether they be means of empirical reporting that are metonymic of larger social relations or means of expressive figuring that are metaphoric of larger social values, be made to address specific conditions? Sekula argues that elements within a work only come to have meaning by attaching to a larger discourse. No specific concretizing or idealizing means can produce a larger consciousness of meaning in and of themselves, as though solely from “inside” a work. Yet when Sekula claims that Hine’s ennobling photograph of the child coal miner and amputee Neil Gallagher leads merely to a sense of generalized pathos, he is begging the question. Sekula does not evaluate whether this ennobling photograph served or failed to serve the NCLC’s aim of building a political consciousness of the conditions faced by child laborers, coal miners, or working-class people more largely. Instead, he assumes that Hine’s idealizing and concretizing representational means and aims are ideologically siloed from one another (as though meaning comes solely from a schema that exists outside the work). Sekula is correct in arguing that no work creates a political position sui generis, but it may well cathect with a nascent moral and political perspective and thereby come to build or sustain a political consciousness.

In using the term “mystic realism,” I flip the word order of Sekula’s “realist mysticism” to resist Sekula’s assumption that tapping into idealizing traditions of representation necessarily compromises the aims and effects of a socially-concerned realist project. While Sekula uses the word “mystic” to refer to spiritually diffuse meaning in order to disparage a “mystic” pole of representation in Hine, I use the word as a term of art for the use of specifiable idealizing means—paradigmatically, a beatifying light that falls kindly upon a subject. Retaining Sekula’s word “mystic” appeals to me here because it provides a general basket for any relevant, traditional source of signal value. Mystic realists characteristically draw on idealizing means from multiple traditional sources of value toward a “religious” cathexis that will direct audiences toward social and political ends rather than toward the orthodoxies associated with those sources. If, for example, a beatifying light that falls upon a poor or working-class subject merely comes to signal Christian goodwill as a religious end in and of itself, that idealizing means neither activates nor even licenses a political intervention and thus has not served social realist aims. In their recourse to idealizing means, mystic realists countenance the risk of producing bad generalizations that distract from specific social conditions. But mystic realists see this risk as one that must be countenanced because they see idealizing means as indispensable to the production of solidarity and of a clear sense of social and political direction. Mystic realists face a representational puzzle. Idealizing means invest class subjects with a sense of value that is indispensable to the project of mounting imperatives to social action, but these means cannot be allowed to distract from specific social conditions for the sake of these same imperatives. The adequation of idealizing means (in Hine, the visual rhetoric of the “great master” tradition) with concretizing means (in Hine, empirical fieldnotes or reportage and the presentational impact of an indexical medium) thus becomes a matter of paramount representational concern for mystic realists. In raising the importance of the adequation (that is, the equilibration or dialectic presentation) of formal means, mystic realists are not focused on “interior” or formalistic criteria of adequation (that is, an aesthetically rich, well-proportioned compositional whole). Rather, they are focused on gauging the “adequacy” of a representational adequation relative to their sense of its ability to confront their audience in a way that achieves the use, end, or effect of aligning that audience with a social side facing injustice. However, a clear sense of representational aims does not make these aims easy to achieve. Mystic realist practice must neither abstract away from its specific, motivating social concerns nor allow social concern to delaminate into an unmoved objectivity or a merely meta-reflexive self-commentary, and thus it proceeds under the multiple pressures of competing demands. The mystic realist dilemma appears like this: How to have the benefit of beatifying traditions of religious representation without the world-transcending implications of those traditions? Given that discourses of objectivity may tend toward neutrality no less than mandarin discourses of modernist form may tend toward social remove, how to produce an adequate analysis of the social world without the dispassion that tends to underwrite discourses of objectivity? How to mobilize selective representational means associated with “high” conceptions of art in order to impart an idealizing force sufficient to subjects that, as class subjects, require some aspect of this without losing focus on social particulars that differentiate the specific conditions at stake from those of “humanity in general?” Mystic realists struggle with the dilemma of how to co-animate concrete particulars capable of generating acute social analyses with larger values and valuings capable of motivating social seriousness, ethical trouble, and coordinated action in presentations that, to the degree that they succeed in this adequation, will prove socially and aesthetically startling.

II: “Realism” as the Demystification of Prestigious Representational Means

In Sekula’s view, however much the separation of self-referential, modernist art practices from explicit social relevance may have once seemed promising in its “autonomy,” these practices were finally and clearly condemned by their inability to address the Vietnam War.5 In the context of widespread repression and atrocity, maintaining the regal remove of high cultural activity appeared increasingly obscene, and thus the need to address the war made a renewed search for a reinvented and reinvigorated social realism urgent. Sekula feels an urgent need both to return to Hine’s social realist practice and to thoroughgoingly reinvent this practice such that it will no longer be tainted by “mystic” expression. However, Sekula does not end up recommending a practice that would attempt to produce politically incisive representations strictly on the basis of empirical, documentary means, as “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning” might lead us to suspect. Instead, approaching photography “as a social practice” ends up requiring metacritical scrutiny of the social and discursive apparatuses within which images are imbricated such that Sekula finds himself searching for a realism that might “brush traditional realism against the grain” in order to reveal these apparatuses.6 The only route available for materialist cultural production turns out to be, in Sekula’s view, the involution of “realist” practice into a self-reflexive ideological critique of representational means. In practice, for Sekula, this entails work in a Brechtian tradition that aims to elicit political dialogue from its audience through the use of sociologically defamiliarizing and self-reflexive captions. In Sekula’s photo works, such as Meditations on a Triptych (1973 and 1978) and School is a Factory (1980), images receive careful analysis in captions and essays closely modeled on Roland Barthes’s “semiological” analyses in Mythologies (1957, translated 1972). Instead of composing portraits that might move viewers, Sekula seeks to unfold portraits, whether found or made by himself, as “already replete with signs” that indicate the covert and often competing intentions of the photographer, the subject, and the discursive context of reception.7 Sekula is seeking to understand the contrastive pictorial paradigms at work within any picture. And Sekula’s talent for distinguishing the poles of discourse by which prestige gets imparted to images comes to the fore as his primary tool.

In his 1978 “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary,” Sekula addresses the situation of contemporary art in which he finds himself. While the formerly dominant paradigm of modernist art’s progressive “purification” had by this time largely collapsed, Sekula finds in its wake merely a new wave of self-referential artistic “end-games” rather than a meaningful break from self-referential modernist practices. For Sekula, “mannerist” pantomimes of mass culture, including much political art, merely offer “a private-party sideshow” and a contemporary “dandyism” that appears especially farcical as such, given transparent efforts to use a professionally-managed art market to profit from this work.8 Sekula bids contemporary artists to interrogate and dismantle their relation to these kinds of ironizing, modernist practices. Sekula then turns to the situation of documentary photography, and he sees the “fetishistic … mannerist … introspective, privatistic, and often narcissistic” work of Diane Arbus as unfortunately characteristic of the kind of practice then getting promoted as documentary (DM, 55). In response, Sekula calls for a critical reexamination of the “social documentary tradition Hine had a hand in inventing” that will make it possible to reinvent social documentary practice without reproducing Hine’s spoiling synthesis of “mythic” empirical force and prestigious pictorial means.9 Sekula describes himself as one among a small group of documentary practitioners who are working to think through a basic question: “How do we invent our lives out of a limited range of possibilities, and how are our lives invented for us by those in power?” (DM, 56). Sekula avoids describing this work as artwork because he suspects that any work that seeks special designation as art ends up attaching itself to carrion ideologies, given that this designation had largely come to be defined by allied discourses of modernism and of the “universality” of humane liberalism. Sekula’s reinvented documentary realism seeks to meta-critically dismantle such aestheticizing discourses. Yet referring to this work as a reinvention of the social documentary tradition of Hine seems odd to me, given that Sekula aims not to renovate but to radically deconstruct this tradition’s core commitments to both evidentiary testimony and ennoblement. “Realism,” for Sekula, ceases to name the project of generating socially concerned representations and comes to name a project of ideologically deconstructing and demystifying cultural representations. Sekula seeks to reinvent realism not as an achievement nor even as a project of art but as a project of critical negation that debunks art as such altogether.

But while his claims are radically sweeping, Sekula also seems to allude to a more specific assessment of the documentary tradition that goes something like this: Hine’s social documentary means of fighting the system and contributing to social uplift with work that had purpose and pathos, work that dignified and did not degrade its subjects, had devolved into means for mass-circulation photo-magazines like Life to sell themselves as serious magazines.10 In this context, “the find-a-bum school of concerned photography,” as Sekula disparagingly refers to it, increasingly failed to attach its photographs to specific organizing campaigns such that they came to function as sensationalizing pictures (DM, 62). Indeed, in such work, “the bum” often gains topicality as an “end game” image of social anonymity and personal tragedy. In the absence of politically incisive directives, viewers are left with a superficial visual relationship to persons suffering from conditions of dereliction, a visual relationship that gives them the pleasure of knowing that they are “better than that,” even if they sympathize with the subjects.

It is with this context in mind that Sekula ends up holding up Martha Rosler’s “unrelentingly metacritical” The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974–75) as paradigmatic of the “reinvented” documentary practice that he recommends (DM, 60). For Rosler, the middle-class target audience of documentary work has proven much more likely to wallow in so-called sympathy or to twist out “generalizations about the condition of ‘man’” from this work than to commit to “change through struggle.”11 Thus, in Rosler’s view, the largely unquestioned “cultural legitimacy” of work that caters to this audience should strike us as obscene.12 In response to this situation, Rosler goes to the Bowery, a Manhattan neighborhood that had become a largely derelict urban space, where a documentary photographer might seek to “find a bum.” Here she takes pictures of littered containers of cheap alcohol, pictures that are to serve as metonyms for the neighborhood’s unhoused, “drunken bum” inhabitants (garbage serves as a metonymic placeholder for people who are considered garbage).13 In The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, Rosler pairs each photographic “urban report” with a typewritten list of drinking-related slang terms—lists that produce a “poetics of drunkenness” and that present alcoholism as “a subculture of sorts.”14 While Sekula starts out by decrying the “fetishistic … mannerist … privatistic, and often narcissistic” work of Arbus, he ends up praising Rosler’s similarly distanced, cool, hip, ironic, and deadpan work because Rosler thematizes the inadequacy of her representational means.

But surely inadequacy is a problem. Tying left politics to a declaration of the inadequacy of representational means undermines the project of using either resurgent or newly innovated means to forcefully present a better, more adequate social vision. Regardless of whether one centers the value of idealizing, evidentiary, or Brechtian means toward their ends, surely the point of a socially- and politically-engaged practice must be to struggle to craft representations that might prove adequate to the aim of spurring social and political engagement. And resisting the temptation to retreat from this struggle seems to me more, rather than less, crucial when conditions of reception pressure this struggle with representational difficulties that cannot be simply or straightforwardly “overcome.”

Sekula attends to an ideological traffic in the meaning of works that so quickly detours audiences from specific tracks of realist testimony onto discursive superhighways that, in his moment, seemed bent to a rhetoric of “universality” that served the U.S.’s Cold War ambitions of global domination. Sekula cannot descry a way to conjure with formal means in order to activate countervailing social and political values without risking the mystifications on which liberal complicity feeds. In Sekula’s view, recourse to idealizing means in representations of social misery gives rise to a sense of aesthetic pleasure that fuels abstractly diffuse mystifications. Among the aesthetic means that Sekula interprets as susceptible to a badly liberal discourse, none disgust him more than deliberate compositional references to the great master tradition and, most especially, to religious iconography from this tradition, in portrayals of social misery.15 Thus, he determines that practitioners should focus on dismantling the ideological import of formal choices through the use of intentionally unemotive and unesthetic, metacritical means. But must we really reject the utility of ennobling means that intensify our response to misery?16 Sekula’s vigilance against the ideological cooptation of forceful and specific works of realist testimony leads him to accede to the cancellation of these works’ means of mounting forceful and specific realist testimony, whereas he might otherwise cause us to resist cooptation more vigilantly. Given that our social imaginations are indeed laden, an effective political strategy demands that the loaded character of the social be taken not only as a subject of meta-reflexive critique but also as a matter for use in the interventional composition of acute and ennobling representations.

In order to have an effective politics, we require a clear sense of what we value and a clear sense of that good (eudaemonia) such that we have a clear sense of direction as to the concrete next steps that might lead to a better society and better conditions. An effective politics is mounted on motivating political aims and thus on motivating values (that is, ideals) that orient us toward the socially better by providing us with a sense of what a socially better world might look like. Indeed, for a politics to acquire a sufficient force of political direction and solidarity, we require motive values that marshal the certainty of the transcendental, and we require a transcendental (that is, certain) sense of the value of the classes of people with whom we are in ultimate solidarity. Artistic practices that solicit audiences to align themselves with an effective politics need to assert motive values and the value of class or group representatives, or they must at least forward their works in discursive contexts that will “attach” these senses of value to the works’ meaning. This is true of practices that support politics that are contemptible no less than it is true of practices that support politics that are praiseworthy.

Acknowledging these basic claims, though, does not imply a slide into cultural boosterism of any social realist work that makes recourse to idealizing means in order to signal left-wing values and the value of poor and working-class people. Such works require means that make the value of class representatives recognizable, lest empirical truth remains on a ground of fallow facts and does not gain directive force, but they equally require the integration of these means with ones that draw acute attention to concrete class conditions, else “value” remains in a sky of ideals and, again, does not gain directive force. Getting this synthesis right proves difficult. We require the directive force of motive values, which further requires drawing from traditional sources that make value recognizable, but this must not result in the imposition of meanings that divert us from the concrete conditions at stake and the need for real change. Meaning often diverts from its concrete stakes because, as Sekula notes, recourse to traditional sources of value seems more to assert something about humanity-in-general than about class struggle—a dynamic upon which liberal complicity feeds. For this reason, mystic realist aims are served by a formal dissatisfaction with means and a constantly renewed effort to critically and tactically gauge the effect of one’s means.17 However, this is true only so long as formal dissatisfaction does not involute into metacritical commentary on the dilemmas of compressing value and acuity in ways that eclipse the underlying aim of mystic realist practice: the formation of a class-conscious “we” directed toward the better. In taking demystification as the aim of metacritical practice, Sekula carves out a space of “autonomy” from what he sees as an otherwise inevitable attachment of meaning to bourgeois discourses. Artworks thus come to seem inert (they only mean by attaching to preexisting, dominant discourses), and sharp, ennobling representations of class end up seeming to need a supplementary rescue from dominant discourses that can only be provided by ideological deconstruction. In criticizing this position, I am neither advocating for an uncritical art of idealization, nor even do I mean to devalue the role that metacritical practices play in revealing problematics. Rather, I mean to insist that by gauging the effect of means relative shifting media-historical and historical conditions, mystic realist practitioners can come to possess a critical power without reducing their capacity to use their means for the sake of forceful, socially commanding solicitations.

In arguing against the position of Sekula, I am seeking not only to intervene in intra-left debates over social realist practice but also to question the allergy to talk of values (and thus to idealizing means that signal values) that marks much present-day scholarship in the humanities. Sekula’s critical enclosure of idealizing means to aestheticizing hokum narrows the field of social and political engagement to the metacritical dismantling of rhetorical forms. Rather than clarifying the differing social uses of means, present-day disillusioning critiques of solicitations to potent value (including solicitations to sympathy and to documentary truth) often similarly narrow the role of socially-engaged thought down to metacritical deconstruction. As a result, the very nature of beliefs and of their categorical assertiveness seems to come under attack. Yet if the idea is that belief as such fundamentally causes problems, meta-criticality about belief-formation does not get us out of these problems. Rather, we end up in the zone of Zeno’s paradox: one stakes an implicit moral claim to a superior moral judgement on disillusionment with discursive invocations of moral judgement. If the problem, then, is instead that we have bad beliefs, criticizing belief as such is not to the point. Rather, metacritical transvaluation should work to renovate and clarify our convictions or means of confronting us with a social reality should direct us to different convictions. Given that disillusioning critiques often harbor a repressed desire to mount positive, rather than strictly negative, political claims, a bit of idealization often gets smuggled through the back door at the eleventh hour for the sake of holding out a thin (mystifying) political potential for an object of critique. For such a potential to take on a politically effective (that is, collective) character, critique needs to build into a “we” with whom we can have solidarity or by whom we can be confronted, which requires a categorical claim to valuing. In arguing against Sekula, I am most of all seeking to establish that the critical inclination to refuse idealizing means and reduce politically-engaged practice to the metacritical ends up punting the issue of our values and of valuing our values down the road.

III: Hine’s Mystic Realism

Sekula’s initial error, in his assessment of Hine, lies in his schematic claim that if Stieglitz’s explicit aesthetics render his politics subsidiary and implicit then it must follow that Hine’s explicit politics render his aesthetics subsidiary and implicit. Given Sekula’s comparison of Hine’s discourse of social realism with Stieglitz’s discourse of modernist formalism, this contrastive claim seems intuitive. As Alan Trachtenberg has so succinctly put it, Stieglitz is doing camera work; Hine is doing social work.18 Yet, Sekula’s claim relies on a fundamental confusion about social realist aesthetics. Sekula’s sense that the explicit orientation of aesthetic means toward social and political ends renders one’s aesthetics subsidiary and implicit accedes to a separation of aesthetics and social engagement enforced by the formalist meaning-cartel that Sekula claims to attack. The assumptions involved in this division remain widespread such that while arts educators and scholars often debate the politics of social realist practices, the aesthetic dimensions of social realist practices are often given short shrift. In orienting the use of aesthetic means toward specific social ends, social realists explicitly participate in the production of social and political rhetoric. In their preoccupation with formal aesthetic means, social realists avoid putting on blinders that would prevent them from discerning the “outside” discourses that will shape the meaning of their work—which is not to say, of course, that for any given practitioner blind spots do not persist. But a blindly intra-artistic focus on aesthetic matters is surely not definitive of what it means to have an explicit aesthetics. Neither gauging aesthetic means relative ends that are conceived of as social rather than as isolatedly aesthetic nor the production of works for venues other than those of the “art world” in any way precludes that a practitioner has an explicit aesthetics. Hine never aimed to present his work in galleries or museums. He staged his pictures in social work magazines and the pamphlets of political organizations for audiences who, unlike the audiences of gallery artworks, were directly engaged in or were being organized to directly engage in campaigns for social change. But this difference in venue does not render his work “less esthetic.” Rather, Hine seeks to harness aesthetic means shared with painting traditions in order to solicit audiences in ways that are politically effective.

In order to reevaluate Hine’s aesthetic practice, I want to first return to Hine’s lecture “Social Photography.”19 For Sekula, simply calling attention to Hine’s quotation of George Eliot in his conclusion of this lecture was sufficient to tar him as a realist of the wrong kind. But understanding what exactly Hine gets out of his nineteenth-century sources requires closer attention to his quotation of Eliot than Sekula was inclined to give:

All honour and reverence to the divine beauty of form! … let us love that other beauty, too, which lies in no secret of proportion, but in the secret of deep human sympathy. Paint us an angel, if you can … [with] a face paled by the celestial light; paint us yet oftener a Madonna, turning her mild face upward and opening her arms to welcome the divine glory; but do not impose on us any aesthetic rules which shall banish from the region of art those old women scraping carrots with their work-worn hands, those heavy clowns taking holiday in a dingy pothouse, those rounded backs and stupid weather-beaten faces that have bent over the spade and done the rough work of the world, — those homes with their tin pans, their brown pitchers, their rough curs and their clusters of onions. …

It is so needful we should remember their existence, else we may happen to leave them quite out of our religion and philosophy, and frame lofty theories which only fit a world of extremes. Therefore let Art always remind us of them; therefore let us always have men ready to give the loving pains of life to the faithful representing of commonplace things, — men who see beauty in the commonplace things, and delight in showing how kindly the light of heaven falls on them.20

This passage, which Eliot builds out of ekphrastic glosses of Dutch genre paintings, offers more than an aesthetic ideology of liberal sentimentality. Eliot describes a representational circuit: idealizing means drawn from religious paintings of sacred history subjects visibly inflect certain genre paintings of poor and laboring-class people such that, paradigmatically, a kindly light falls upon a faithfully class-particularized subject. This specific genre painting tradition, with its simultaneously ennobling and veristic means, provides Hine with a compositional model for forwarding poor and working-class subjects as subjects of world-historical importance. Thus, in Young Russian Jewess at Ellis Island, the light that falls upon Hine’s subject comes forward as if from Johannes Vermeer’s genre paintings as a rhetorical means to portray the young migrant woman in a reverential light.

In both the Hine and the Vermeers, light streams down a diagonal from a high source yet quickly diffuses to soft light and shadow such that it does not wash out but rather gives dimensionality and tactile tangibility to the subject. Each work features a compositionally structural window, yet in the Hine, the light that falls upon the subject’s face comes from an unseen source out of frame and thus seems all the more inflected by annunciatory, baptismal, and beatifying pictorial precedents.21 In each work, a simultaneously restrained and intense treatment works to highlight the subject’s innerness, a subjectivity that at once seems calmly collected and to be dreaming of something beyond their current conditions and situations of waiting. We as viewers are not able to know the individually perspectived contents of the subject’s own-most thoughts. Even though Hine’s setting is not that of a domestic workplace but rather that of a massive infrastructure for processing poor migrants as masses, our regard retains a degree of intimacy, but that degree of intimacy does not eclipse difference and distance. With regard to each of these subjects, we are aware that their social position is subject to all kinds of disparaging rhetoric, including, for this Jewish Russian emigrant, much racist rhetoric. Dignifying portrayal of these class subjects thus works to shift the rhetorical space in which we see them so that we can appreciate their potent personhood, an appreciation toward which the works’ combination of understatement and powerful statement conjures us. The collected and dreaming attitude of the subject evinces social values (of modesty, of honesty, and of measured endurance), while effusiveness of kindly light and portrait seriousness raise a high regard for the subject in a way that draws our attention to, rather than distracts from, particulars. Indeed, in the Hine, the background of the Vermeers keys our attention to this subject’s specific headgear and the specific thick, glazy texture of her workwear clothing. Unlike Vermeer’s subjects, Hine’s subject endures a dailiness of a differently epic order, in a historical moment of massive demographic movement of the poor (from, through, and to difficult conditions). This larger social picture emerges with especial force when we notice how the light glares down a single shiny crease on and down from her right shoulder—the deep impress left by a luggage cord. Powerful particulars like this one are reliant upon generic typifications that call our attention to them. Idealizing means do not reduce the “young Russian Jewess at Ellis Island” to an “ideal.” In denying that she is no more than a case, these means do not etherealize her but rather collaborate with the report of an indexical medium to deepen our relation to a social reality.

While Hine’s captions typically provide sociological details about his subjects, he here recruits a quotation from Whitman, on tiring but tireless seeking, to this woman’s emigrant experience because, in this case, their lack of a shared language had made an interview impossible. For Hine, Whitman stands alongside Eliot as a major nineteenth-century source of inspiration, as one who exemplifies a comradely concern for the specificity of each person’s labor and class conditions that pushes readers to feel the striving ardor that lies at the core of each person.22 Appreciation of conditions that split society along lines of class, race, gender, and region pains and intensifies Whitman’s appreciation of ardor such that it scales up as part of a ceaseless poetic intercourse among the individual and the region or city on up to the cosmos and back. Through an unending concretizing-idealizing circuit that is doggedly and sometimes ecstatically bent toward a vision of the better (one that is immanent to our collective potential), Whitman insists that each’s ardor might yet be made to cathect and build together. For Whitman, the vitality of the particular and of the universal lies in the grainy, sensation-thrilling texture of their imbrication—a vitality, in other words, that is experiential rather than intellective. By recruiting Whitman’s lines on seeking to his photograph, Hine charges our regard with a degree of monumentality, even as his focus, in contrast to Whitman’s concern for going big, stays on the side of a concern for a concrete social situation, for this concrete but not discrete subject.23

For Hine, compositional typifications (typifications at the impacted or multiply inflected nexus of religious, genre, and portrait traditions, especially) give visible type to an undeniable dignity. Compositional references to carefully selected art historical precedents provide forms of visual rhetoric that draw forward with them a transcendental sense of value that ennobles poor and working-class subjects. The social photograph, for Hine, joins a visible typification of undeniable value together with an evidentiary typification of undeniable injustice. In doing so, the social photograph seizes means of producing prestige from great master painting in order to direct audiences to regard poor and working-class subjects as world-historical subjects. In this way, the social photograph seeks to participate in collective class struggle by a revolutionary seizing of representational importance that demotes Establishment perspectives and promotes, in their stead, social realist perspectives. The means of producing this kind of rhetorical challenge are not simply those of “artiness” (Steichen’s artifying means, for example, would not serve this purpose), and the end at stake is not simply the elevation of photographic work as high art culture (as with Stieglitz). Hine is concerned neither with the ontological status of Art nor with the ontological status of realism but with the carefully gauged use of aesthetic means provided by the history of art and by a new indexical medium for the sake of social and political ends.

For Hine, the potential capacity of social realist photography to seize for itself a high and leading cultural role bestows on practitioners a duty to compose pictures of poor and working-class subjects with a great deal of care. For Hine, this means that, to the degree that practitioners have an explicit politics, practitioners must develop an explicit aesthetics. Specifically, Hine recommends that social realist photographers draw upon idealizing means of the art historical tradition, especially visual rhetoric that has followed a circuit from religious painting and through genre painting, to produce potent portraits of empirical subjects of social misery. Yet, Hine emphasizes the potency of idealizing means precisely because he sees their potential to dovetail with a powerful concreteness provided by the medium of photography and not because he considers concretion less important than ennoblement. Hine appreciates that, in his media-historical moment, viewers receive the photograph as an indexical image, as the concrete image of a concrete subject there, such that, as he claims in “Social Photography,” “The photograph has an added realism of its own” (SP, 356). Whereas Sekula points to a “mythic aura of neutrality,” Hine points to a social reality that, mythic or not, intensifies the ethical obligation of practitioners to approach the work of picturing their subjects with the greatest seriousness and care (values that are then to orient the regard of viewers as well).24 For Hine, if the photograph’s supplementary force of signal concreteness gives presence to a concrete subject there, social realists have a special opportunity to wed this supplementary force with that of a signal ennoblement so that this presence will testify to a potent personhood there. Through this synthesis, Hine pushes the “Romantic-Realist” social vision of Whitman and Eliot toward concrete political uses within specific campaigns for social change.

Hine marks empirical abuse in its specificity with subjects who he often identifies by name: Neil Gallagher, Addie Card—subjects who are not anonymous, who are not just a case or example, but who appear both with the representative status of victim and with individual dignity. Yet for all his deliberation over the aesthetics of the social realist photograph, Hine’s social and political aims do not ride on an outsized faith in visual testimony. While Hine was not always able to author the articles in which his photos appeared, his photos consistently come “backed with records of observations, conversations, names and addresses” that clearly mark the conditions and compensation of specific forms of labor.25 Hine’s practice brings together sociological records and condensed and vital photographic compositions that provide supportive evidence for his labor surveys (as any snapshot might) and that further express the ardor for conditions of dignity that lies at the core of each person.

For Hine, the faces that stand behind the photographic products of his camera also stand behind consumer products, and his political and aesthetic practices aim to facilitate their ability to come forward from behind the veil of commodities to confront viewers. Hine addresses the dominant, consumer-side view that “many of our national assets, fabrics, photographs, motors, airplanes and what-not,—‘Just happen,’ as the products of a bunch of impersonal machines under the direction, perhaps, of a few human robots.”26 Due to the pervasiveness of this ideology, viewers need to be confronted, as though through the photograph, with the “sweat and service that go into all these products.”27 “Back of them all,” Hine writes, “are the brains and toil” of laboring persons.28 Indeed, Hine structures the articles and pamphlets that he himself wrote according to a rhetorical movement from the commodity to that which lies back of its concealing veil: conditions of labor experience that he has carefully investigated and that he seeks to keenly register.29 In Hine’s 1913 article, “Baltimore to Biloxi and Back: The Child’s Burden in Oyster and Shrimp Canneries,” photographs and sociologically detailed description collaborate to vivify the social realities that lie back of the shrimp or oyster tin. Hine ushers the reader to the middle-of-the-night hour when workers wrench themselves from the hazardous sheds in which they are warehoused for six months of seasonal labor to prepare for the four a.m. start to the working day:

Come out with me to one of these canneries at three o’clock some morning. … Near the dock is the ever present shell pile, a monument of mute testimony to the patient toil of little fingers. It is cold, damp, dark. … See those little ones over there stumbling through the dark over the shell piles, munching a piece of bread, and rubbing their heavy eyes. Boys and girls, six seven and eight years of age, take their places with the adults and work all day. … When they are picking shrimps, their fingers and even their shoes are attacked by a corrosive substance in the shrimp that is strong enough to eat the tin cans into which they are put. The day’s work on shrimp is much shorter than on oysters as the fingers of the worker give out in spite of the fact that they are compelled to harden them in an alum solution at the end of the day. Moreover, the shrimp are packed in ice, and a few hours handling of these icy things is dangerous for any child. … If a child is sick … [the child] wanders around to kill time. … The baby at Ellis Island little dreams what is in store for them.30

A company cemetery houses many children killed by these conditions, “one of the ‘conveniences’ that the company does not boast about,” Hine supposes.31 Hine channels his outrage into an effort to register the Tetris-effect inducing process of cannery work: “standing, reaching, prying, dropping—minute upon minute, hour upon hour, day upon day, month after month,” until every ounce of effort and stamina is sapped from mind and body.32 Hine’s 1914 article, “Children or Cotton?,” likewise summons the reader with the call, “come out with me at ‘sun-up’ and see them trooping in the fields.”33 At first, he writes, you might be struck by the beauty of the dawn fields, but stay longer, “watch them picking through all the length of a hot summer day, and the mere sight of their monotonous repetition of a simple task will tire you out long before they stop. … You will realize that for them even in the beauty of the early morning the fun has quite lost its savor” (CC, 589). Hine writes, “The motions are simple and easily learned. After that it is a question of nimble fingers and endurance. Pick,—pick,—pick,—pick,—drop in the bag—step forward; one hundred bolls a minute—six thousand an hour—seventy-five thousand a day. This for six days in the week, five months the year, under a relentless sun” (CC, 589). Hine’s ardurous concern for the experience of each child laborer (and the enormous time scale of this experience as it cumulates to weariness, pain, and baffled striving) combines with a cumulative articulation of the immense class scale on which these conditions exist: these are conditions that, “in the one state of Texas,” dominate the lives of “a quarter million children” (CC, 589). In order to make the moral and political truth of the injustice and class sides at stake here unmistakable, Hine then draws upon the sacred historical figure of Herod (who orders the Slaughter of the Innocents): “It is high time for us to face the truth and add to our indictment of King Cotton, a new charge—the Herod of the fields” (CC, 589). Hine contrasts his indictment with a local newspaper report that celebrates a child’s exceptional weigh-in, that is, the yield of an “incessant grind, long hours, physical strain” that must be made to appear “appalling!” (CC, 590). Hine’s carefully composed portraits of child laborers solicit viewers to register the value and undeniably potent personhood of each empirical child laborer. Meanwhile, his text seeks to school our reception of the beauty of these pictures such that, far from abstracting away from the conditions at stake, they “bid us summon our keenest social imagination” to reckon with the injustice of “monotony, toil, and baffled hope” (CC, 590). These solicitations do not simply elicit a sense of poignancy; rather, in Hine’s articles, they mobilize readers to involve themselves in the concrete campaigns of the NCLC, something that, just as a start, readers’ by now clear picture of conditions and of values demands.

Although Hine aims to use expressivist means in order to express the dignity of his subjects, Sekula claims that Hine’s expressivist means instead cause his representation of a “victim” to lose its critical edge and to signal, more than anything else, the Genius of its Author. To the contrary, I believe that Hine’s realist-expressivist synthesis of means manifests another voice, another social reality, another narrative there, exilic, back of veiled social relations and beyond a pathologizing rhetoric of squalor, of this emigrant, worker, or out-of-work person who is not only a victim. When a critic claims, as I have here, that a work portrays a poor or working-class person with meaningful dignity, they are claiming that the portrayal does not merely come to signal something about its author. Or, to formulate this dynamic more precisely: to claim that a work portrays meaningful dignity is to make a heuristic judgement that an adequation of idealizing and concretizing means has compressed registration of concrete conditions and of potent personhood into forceful co-presence.

With Hine, we see individuals shown in tough conditions coming forward as a class, in a class of images wherein the person facing a situation of injustice, whether a man or woman, a child or adult, working or jobless, looks noble, looks like a hero. Much as the subject of Young Russian Jewess at Ellis Island comes forward with the idealizing means of Vermeer’s genre paintings, so in Power House Mechanic Working on a Steam Pump (1920) a bare-chested worker comes forward with the compositional form and classical, ennobling rhetoric of the Discobolus by Myron.34

Yet this ennoblement does not reduce subjects to an ideal or a cliché; they are put forward not as an Establishment noble nor as a “star” but as this person with a job, this person out of a job. Hine is engaged in an effort to change the perspectives of those who encounter his works by aesthetically mediating portraits of individuals such that they come forward as a class in a way that builds class-consciousness. To the degree that such works succeed in motivating collective struggles to make conditions of the present those of the past, the social realist photograph, as Hine proclaims in “Social Photography,” can come to play a vanguard role as “our advance agent” (SP, 357). For Hine, aesthetic mediation is an indispensable aspect of political efforts to build class-consciousness—that is, identification as part of a “we” that shares a perspective on class conditions. As Lukács writes in History and Class Consciousness, when one sees specific conditions as representative, one comes to see the social relations at stake in those conditions as representative, and thus one can identify as part of the “subjective ‘we’” of solidaristic class-consciousness.35 Seeing that one is a member of a class of workers de-fragments the social complex, dis-alienates one from individualized isolation, and marks the birth of the “we” as a living word that inaugurates our capacity for collective and conscious intervention. A critical picture of a society in need of reconstruction and solidaristic class-consciousness emerge together on the basis of a clear view of social class structure and an idealizing cathexis with a ”we,” with people who share conditions and who share a potential for collective action. For Lukács, a critical class picture is one that “go[es] to the heart of the facts” by showing the authenticity of objective conditions—one, that is, that mediates the whole of the class structure by showing the socially real as a subject of dis-alienating and ennobling class identification.36 For Hine, practically vivified social facts can express the quality of existences, of lives directly exposed to the day-to-day exigencies of a labor system that arbitrates one’s social conditions and position. In both Hine’s images and Lukács’s theory, history comes to be revealed through workers’ self-knowledge of their aspiration such that the dialectic, taking the next step, cannot be unyoked from aspiration, from the this-sidedness of truth as what is relevant to taking steps toward change. In Hine, as we have seen in his articles on the cost of the oyster tin and the cotton dress, social facts gain practical vividness not simply through documentary directness but through investigations and mediations that work to unveil the social realities of commodity production. In the context of his articles, Hine’s ennobling portrayal of class representativeness seeks to overthrow the objectness of the commodity-form in the truth of sweat and toil, brains and persons subject to unjust class relations.

Absent their own active organizing efforts as part of poor and working-class struggle, there is no aesthetic formula that can magic bourgeois viewers into seeing things this way. We mystify the utility of political art if we expect it to have a power of political suasion possessed by no other means of political canvassing. From the perspective of a bourgeois “we,” diverse kinds of representations of poor and working-class subjects can be interpreted in a way that confirms normative bourgeois values and that mutes calls to align oneself with a class side facing injustice. Recognition of an abstract “universality” leads to construal of “equality” as something that has already been (abstractly) granted, whereas recognition that a class structure unjustly inflicts conditions of inequality leads to a dialectical imperative to defeat those conditions. By sheering from conditions toward a formalistic humanism that absolutizes abstract diffusions, empirical reality is made into something that is scholastic and probably insoluble. By focusing on specific conditions toward a dialectical materialist humanism that illuminates the class representativeness of those conditions, empirical reality is made into something that bears clear political directives. Where one viewer sees something abstractly diffuse, another sees ennobling “emergence as a class,” as part of a politics that, while metacritical analysis may show it to be mounted on “bourgeois rhetoric,” has been made to function beyond all bourgeois expectations for transformative aims.37 By revealing that the basic structure of the labor system produces injustice, by confronting one with the truth of the class side that faces injustice, and by making the question of the class side with whom one ought to be aligned unequivocal, social realist art aims to change one’s class perspective. If one aims to try to address those with bourgeois perspectives, representational adequations need to make these truths startling unmistakable, lest they be received only “immediately” as an isolatable empirical aberration or only “mediately” as an abstraction isolatable from motive political meaning. But regardless of one’s target audience, concretizing and idealizing means must collaborate to reveal a kind-ness, a representativeness upon which there falls something like a kindly light, in order for consciousness of class and class contest of the status quo to emerge, in order to mount comprehension of empirical conditions into a politics and into efforts toward the socially better.

Among social realist artists more largely, mystic realist practitioners aim not just to present subjects as cases of social misery produced by a larger social edifice but to present subjects as souls. Whether in Whitman, in Hine’s fellow contributors to Survey, such as Du Bois, or in Sekula’s contemporaries, such as Allen Ginsberg, the mystic realist talk of souls does not invoke anything religiously orthodox but rather means to insist on the potency and dignity of their subjects. Representations that confront one with “souls” are ones that confront us with a metaphysically-invested, indisputable sense of a powerful personhood there that mandates an ethical recognition of and relation to that subject. Such representations harness their available means to produce a powerful sense of “presence” that activates the viewing/reading subject’s sense of the represented subject’s own “voicing” of inner spirit and striving. For Hine, practitioners achieve this representational effect by ensuring that subjects appear with the specific conditions and exigencies of their lives there and by ensuring that we see these conditions authentically as those of a class (a class that lies back of the production of all infrastructure and commodities). For Hine, concretizing means (provided by an indexical medium and notes that record precise conditions), idealizing means (provided by visual rhetoric that makes the dignity of his subjects unmistakable), and larger analyses of labor systems (provided by articles and lectures) hook together. These elements adjoin in a dense aesthetic and political compression that enjoins us to the feeling of another voice or soul who comes forward as a presence that we register as distinct from either the photographer and social investigator or from oneself as a viewer and reader. The “extreme” character of mystic realists’ representational desiderata makes sound critical evaluation of their works difficult. In considering works made with mystic realist ambitions, there is no way to draw a precise line between a type of adequations of idealizing and concretizing means that proves effective in engaging audiences with collective fronts of class struggle and a type that does not. In my view, this increases the importance of efforts to heuristically evaluate and to parse works that appear to exemplify a capacity to build class-consciousness and sharpen awareness of specific conditions and works that appear more so to yield a diffuse, motiveless sense of “value.” Otherwise, one is apt to slide into wholesale boosterism of works that very much countenance the risk of producing bad generalizations that distract from specific, politically laden conditions or into wholesale discounting of means that are indispensable to the mounting of an effective politics.

With Hine, across the time-fields of photographic production and photographic reception, class subjects face each other. Hine’s critical class pictures disclose a labor system that sustains specific, enormous, daily, and unremitting tragedy, and they imperatively demand that we recognize the need for a world structured differently. But the pictures (and Hine’s venues more largely) also leave major questions unanswered or only partially answered: What practical conditions provide goal-worthy aims both for taking the next concrete political step and for a larger social vision? How do we strategically navigate the terrain of the possible and of organizing for the sake of fundamental reorganizations of society? Does the dire need for melioration of social misery provide a directive for developing relationships with philanthropic agents of capital, who represent the wealth needed for such melioration, or not, and if so, how can we do this without compromising efforts to organize labor against capital? In organizing and mobilizing for the sake of workplace victories, when does conciliation with management constitute our victory, and how can organized labor build toward revolutionary forms of change? Neither reformist charity nor militant organizing won conditions warranting the name of class peace, of human communality. But Hine’s mystic realist practice did and does sustain and sharpen consciousness of daily class struggles and of class relations. It would be hypocritical, given that I have criticized Sekula and the Partisan Review for falling into cultural defenses, were I not to clearly claim my own cultural defense of mystic realist practice. However, this does not imply a defense of any primal image of a muscled worker or any portrait of a migrant woman graced by a beatifying light. Hine’s portraits are not stereotypical models for mystic realist practice largely, and mystic realist works do not need to draw upon the exact same means that Hine draws upon or to look similar to Hine’s work. Rather, I am seeking to defend an effortful gauging and renewal of selectively chosen idealizing and concretizing means oriented by the aim of using these means to sharpen awareness of daily class struggle and to build class-conscious solidarity. Indeed, defending such efforts feels to me imperative because I also revere them (the practical truth is that my relation to the social realities and motivations at stake rides on an idealizing cathexis). At bottom, “what one reveres” means what one considers real and what real thing one values as core.

Notes

In this article, I present a critical framework for reconsidering social realist works that make central use of “idealizing means,” that is, representational means that signal the value of represented subjects. Social realist artists who aim to counter the social devaluation of poor and working-class people necessarily draw on idealizing means from traditional, ennobling sources in order to give the value of poor and working-class subjects a recognizable form. In the above photograph, for example, Lewis Hine makes compositional reference to the “great master” tradition and, in particular, to Vermeer’s genre paintings so as to key viewers to see this emigrant woman both in her class-specificity and with the idealizing religious rhetoric of the “beatifying light” that falls upon her. In drawing upon the idealizing means of “high” artistic traditions, Hine attaches poor and working-class subjects to the “metaphysical” or transcendental sense of value associated with these means. I call social realists like Hine “mystic realists.” Mystic, in my use of the term “mystic realism,” specifically refers to the use of idealizing means to secure representational pointedness about the value of subjects contending with unjust conditions.

However, mystic realists do not draw upon idealizing means simply or only to compel audiences to recognize the value of poor and working-class subjects. Idealizing means must further be made to express “motive values,” that is, values that motivate and guide social engagement and that challenge audiences with directives to social change. Mystic realists predominantly draw upon religious traditions for their idealizing means because, while idealizing means drawn from any prestigious representational tradition may underline the value of subjects, religious rhetoric seems to harbor a special capacity for motivational urgency. Religious rhetoric has the capacity to call upon audiences not only to recognize value or hold values but to act according to those values. Mystic realists seek to appropriate the motive urgency of religious cathexes and convictions in order to call audiences to social and political action. They seek not only to extend traditions that beatify ordinary and common conditions but to further beatify the inner striving of class representatives in a way that urgently motivates audiences to join a political struggle for better conditions.

In their recourse to traditional and especially religious means of signaling value and bearing values, mystic realists countenance a number of risks. They risk abstracting away from or covering over attention to specific conditions. They risk seeming to tie the need for better conditions to the “deservingness” of those subjected to unjust conditions—a sense of justice mediated by subjects’ ability to appear under the sign of normative values. And they risk interpretations of their work that write subjects into the wrong kind of religious teleology (the subject will have the recompense of heaven) rather than into the right kind of political teleology (we will struggle in solidarity with the subject to overcome injustice). Yet in contrast to conceptions of socially-engaged realism as a literalistic project of representation that avoids idealizing means in order to avoid these risks, mystic realists insist upon the indispensability of idealizing means both for the sake of portraying the dignity of their subjects and for the sake of building a shared political consciousness. Moreover, they insist that idealizing means do not inevitably divert audiences’ attention from specific conditions; to the contrary, by critically gauging the effects of rhetorical and craft choices, idealizing means can be made to key viewers to specific social conditions. Social realists who strictly tie their practice to literalistic means turn political confrontation into a matter of simply “seeing what’s there.” Yet a mere recognition of conditions that are real does not necessarily yield alignment with a struggle aimed at social repair, just as a mere recognition of the value of poor and working-class subjects does not necessarily yield political urgency. In certain contexts, one may indeed experience motive values as immanent to objective conditions—for example, when one has been mobilized as part of a collective struggle for better conditions. Just as patently, in other contexts, one may experience their knowledge of conditions, whether it be direct knowledge or knowledge drawn from representations, in a way that is disarticulated from and fails to lead to imperatives to social and political action. Mystic realists address this problem of disarticulation by making recourse to idealizing means and especially to the idealizing means provided by religious traditions. This recourse does not imply that one needs to have a religion to have motive values. Rather, religious traditions have a special utility for mystic realists because they are explicitly and unmistakably value-bearing traditions. For all that these traditions may mystify, they also bring analytical clarity to the relation between motivation and the valuing, idealizing, and hierarchizing of a better on which motive solicitations fundamentally (that is, metaphysically) depend. Where mystic realists are explicit about their relation to ennoblement and motive ideals, strictly literalistic (and strictly secular) projects of social representation are inexplicit. For mystic realists, papering over the relation between signal forms of valuing and political motivation serves neither the aim of producing urgency in response to class conditions nor even the aim of producing clarity about these conditions.

I: Sekula contra Mystic Realism

This conception of a mystic realist problematic first emerged in my thinking in response to the classic 1975 essay, “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning,” by photographer and critic Allan Sekula. In this essay, Sekula argues that claims about the meaning of a given photograph can never be developed solely on the basis of elements within that photograph. Instead, photographic meaning is “invented” through interpretations that attach elements within the photograph to the rhetoric of larger discourses. Sekula here attacks critics Benedetto Croce, Roger Fry, and Clive Bell for operating like a “photographic meaning” cartel that restricts interpretation to the discourse of expressionist-modernist formalism and restricts us from political interpretations that contest the status quo. For Sekula, formalist discourse thus masks the social character of its tendentious idealization of “art” and of its concomitant devolution of formal concerns “into mystical trivia.”1 In doing so, this discourse serves elite classes as a quasi-religious opiate that deadens consciousness of the social meaning of class sides by making meaning into a matter of mystifying abstractions and diffusively “spiritual” or “universal” feelings.